Skin infection with bacteria may be a primary problem (e.g. impetigo) or a complication of another skin disease (e.g. atopic dermatitis). Nomenclature of these diseases often reflects the site and the depth of infection – that is, from the stratum corneum to the subcutaneous tissue (Fig. 61.1) – as well as the suspected causative organism.

Staphylococcal and Streptococcal Gram-Positive Cocci Skin Infections

Streptococcal infections may be complicated by acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis; this occurs in <1% of patients in high income countries, but it remains a significant problem in low-income countries.

IMPETIGO

• Major organisms are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci [GAS]).

• A very common, highly contagious bacterial infection, most commonly seen on the face or extremities of children; usually the skin is eroded with overlying ‘honey-colored’ crusts, but there is a bullous variant (Fig. 61.2).

• Interestingly, bullae formation due to S. aureus can be explained by local release of an exfoliative toxin that binds to desmoglein 1 and leads to dissolution (i.e. acantholysis) of the upper epidermis (see Chapter 23).

• Risk factors for infection: nasal carriage of S. aureus and breaks in the epidermal barrier, e.g. atopic dermatitis, arthropod bites, trauma, scabies.

• DDx of eroded lesions: insect bites, prurigo simplex, dermatitis (e.g. atopic, nummular), herpes simplex viral infection.

• DDx of bullae: bullous insect bites, thermal burns, herpes simplex viral infection, and occasionally autoimmune bullous dermatoses.

• Rx: local wound care (including soap), removal of crusts by soaking; for mild cases, topical mupirocin or retapamulin; for moderate to severe infections, oral antibiotics, the choice of which is dependent on prevalence of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the local community (Table 61.1).

ECTHYMA

• Most commonly secondary to Streptococcus pyogenes.

• Ulceration with hemorrhagic crust that extends into the superficial dermis, i.e. is deeper than impetigo (Fig. 61.3); can heal with scarring.

• Often on the lower extremities, and risk factors include an edematous limb, arthropod bites, and a pre-existing ulceration.

• Rx: see Table 61.1.

BACTERIAL FOLLICULITIS

• Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause, followed by gram-negative bacteria; the latter can occur in patients with acne vulgaris on long-term antibiotic therapy; see Chapter 31 for Pseudomonas folliculitis.

• Usually superficial, but occasionally deep, infection centered on hair follicles (see Fig. 61.1).

– Superficial – 1- to 4-mm pustules on an erythematous base (see Fig. 31.2); centrally, a hair shaft may be noted.

– Deep – also referred to as sycosis – tender, erythematous papulonodules, often with a central pustule.

• Commonly in the beard area, on the upper trunk, or on the buttocks and thighs; shaving can be an exacerbating factor.

• DDx: culture-negative (normal flora) folliculitis, acne vulgaris, folliculitis due to fungi (e.g. Pityrosporum) or viruses (e.g. herpes simplex virus), rosacea, and pseudofolliculitis barbae (see Chapter 31).

• Rx: for superficial form – antibacterial washes (e.g. benzoyl peroxide, chlorhexidine) or topical gels (e.g. combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide); widespread staphylococcal folliculitis – oral antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

ABSCESSES, FURUNCLES, AND CARBUNCLES

• By definition, a furuncle involves a hair follicle; involvement of multiple, adjacent follicles is termed a carbuncle (see Fig. 61.1).

• Most common organism is S. aureus, and this is the most frequent presentation for community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA).

• Clinically, furuncles appear as firm, tender, red nodules; carbuncles begin similarly but become larger in size and can develop multiple draining sinus tracts.

• Common locations are the face, neck, axillae, buttocks, perineum, and thighs.

• DDx: ruptured epidermoid inclusion cyst, hidradenitis suppurativa, and cystic acne.

• Rx: fluctuant lesions should be incised and drained; systemic antibiotics are generally reserved for: (1) furuncles around the nose, in the external auditory canal, or in other locations where drainage is difficult; (2) severe or extensive disease (e.g. multiple sites); (3) lesions with surrounding cellulitis/phlebitis or associated with signs or symptoms of systemic illness; (4) lesions not responding to local care; and (5) patients with concerning comorbidities or immunosuppression (see Table 61.1 for Rx options).

ERYSIPELAS

• Most commonly due to Streptococcus pyogenes.

• Represents infection of the superficial dermis along with significant lymphatic involvement; often on the face and neck or the leg.

• Presents as a well-defined area of hot, indurated, bright erythema that is painful and tender (Fig. 61.4); occasionally, there may be superimposed pustules, vesicles, bullae, or areas of hemorrhagic necrosis.

• Favors the young, debilitated, elderly, and limbs with edema or lymphedema.

• DDx: cellulitis, erysipeloid breast cancer, irritant contact dermatitis, early necrotizing fasciitis or herpes zoster, erysipeloid, Sweet’s syndrome, and if it involves the ear, chondritis.

• Rx: 10- to 14-day course of penicillin if due to Streptococcus pyogenes, with route depending on the severity and risk factors.

STREPTOCOCCAL INTERTRIGO/ PERIANAL DISEASE

• Presents as patches of erythema, especially in children (see Fig. 61.4 and Table 60.5).

• DDx: outlined in Fig. 13.4 and Table 60.5.

• Rx: 7- to 10-day course of a first-generation cephalosporin (see Table 61.1) or penicillin.

CELLULITIS

• Most commonly due to Streptococcus pyogenes or S. aureus; in diabetics and immunocompromised hosts, other organism (e.g. gram-negative bacilli) may be the cause.

• In children, Haemophilus influenzae can be a cause of cellulitis, but its incidence has decreased since introduction of the H. influenzae vaccine.

• Infection of the deep dermis and sometimes the subcutaneous fat (see Fig. 61.1).

• Skin rubor (redness), calor (warmth), dolor (pain), and tumor (swelling) are present; more ill-defined borders than erysipelas and may have skip areas; can become bullous or necrotic (Figs. 61.5 and 75.8).

• Systemic symptoms include fever, chills, and malaise; CBC usually shows leukocytosis and bandemia.

• Risk factors for cellulitis of the lower extremity include previous DVT, previous cellulitis with lymphangiitis, chronic edema, and tinea pedis (especially in patients who have undergone saphenous venectomy).

• DDx: on the lower extremity, lipodermatosclerosis and stasis dermatitis (see Fig. 11.5); elsewhere, erysipelas and the early stage of necrotizing fasciitis, as well as causes of pseudocellulitis (Table 61.2).

• Rx: see Table 61.1.

BLISTERING DISTAL DACTYLITIS

• Most commonly secondary to GAS or S. aureus.

• Localized infection of the volar fat pad of a finger or, less often, a toe; occurs most commonly in children.

• Initially erythema and swelling of the skin, followed by development of one or more vesicles or bullae.

• Rx: drainage of blisters and systemic antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

BOTRYOMYCOSIS

• Most commonly caused by S. aureus, followed by Pseudomonas spp.

• Cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules that may have superimposed pustules, purulent discharge, or become ulcerative or verrucous; often in immunosuppressed hosts.

• Grains, representing macroscopic colonies of bacteria, are seen in biopsy specimens as well as the pustular discharge; grains are also seen in eumycotic and actinomycotic mycetoma (see Chapter 64) and actinomycosis (see below).

• Often develops at sites of trauma.

• DDx: ruptured epidermoid cyst, abscess, mycetoma, actinomycosis, and atypical mycobacterial or dimorphic fungal infection.

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

• Usually represents polymicrobial infection with both anaerobes and aerobes; ~10% secondary to GAS.

• Rapidly progressive necrosis of subcutaneous fat and fascia that leads to undermining and ulceration; may have a foul discharge.

• Risk factors include older age, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, peripheral vascular disease, and immunosuppression.

• Initially may resemble cellulitis, but associated pain is often out of proportion to the clinical findings; additional clues include tense edema and a violaceous or gray color reflecting impending necrosis (Figs. 61.6 and 75.9).

• Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion; when anogenital, it is referred to as Fournier’s gangrene.

• Patients may have fever, chills, malaise, and leukocytosis.

• Dx: outlined in Fig. 61.7.

• Rx: surgical debridement is the mainstay of therapy; broad-spectrum IV antibiotics.

PYOMYOSITIS

• Primary bacterial infection of skeletal muscle, most commonly with S. aureus (see Fig. 61.1); associated with immunosuppression, including HIV infection.

STAPHYLOCOCCAL SCALDED SKIN SYNDROME (SSSS)

• Secondary to S. aureus, phage group II strains, which produce exfoliative toxins that bind to desmoglein 1 and lead to dissolution (i.e. acantholysis) of the upper epidermis.

• More commonly seen in infants and children; occasionally, adults with chronic renal insufficiency can develop SSSS.

• Prodrome of malaise, fever, irritability, sore throat, and tender skin; purulent rhinorrhea or conjunctivitis may be present because the initial site of staphylococcal infection is usually extracutaneous.

• Tender erythema on the face and in intertriginous zones that generalizes to the remainder of the body over 1 or 2 days; due to the split in the upper epidermis, the skin becomes ‘wrinkled’ and then sloughs over 3–5 days, leading to denuded areas; on the face, radial fissures with scale-crust develop around the mouth and eyes (see Fig. 3.11).

• DDx: sunburn, drug reaction, Kawasaki disease (erythema often first appears in the groin), Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN; usually affects older children and adults, has mucosal involvement, and nearly always drug-induced).

• Rx: hospitalization and IV anti-staphylococcal antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME (OTHER THAN STREPTOCOCCAL) (TSS)

• Secondary to Staphylococcus aureus, which produces an exotoxin, toxic shock syndrome toxin-1.

• Case definition of staphylococcal TSS is outlined in Table 61.3.

• Historically associated with menstruation and tampon use, but nowadays with surgical packing, meshes, and cutaneous infections (e.g. abscesses).

• Sudden onset of high fever, myalgias, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, and pharyngitis; hypotension is a key finding.

• Clinically, scarlatiniform changes initially appear on the trunk and then spread centrifugally; erythema and edema of the palms and soles can be followed by desquamation 1–3 weeks later.

• Mucous membrane findings: erythema, strawberry tongue, hyperemia of the conjunctivae (Fig. 61.8).

• DDx: streptococcal TSS, drug reaction plus hypotension from sepsis; in children, Kawasaki disease and scarlet fever.

• Rx: hospitalization and IV antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

STREPTOCOCCAL TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME (STREPTOCOCCAL TSS)

• Secondary to GAS (especially M types 1 and 3), which produce exotoxins A and/or B.

• Case definition of streptococcal TSS is outlined in Table 61.3.

• Most common site of the associated streptococcal infection is the skin, e.g. cellulitis or necrotizing fasciitis.

• Rx: hospitalization and IV antibiotics (see Table 61.1).

SCARLET FEVER

• Secondary to GAS, which produce erythrogenic toxins types A, B, and C.

• Seen in children (ages 1–10 years), usually following streptococcal tonsillitis or pharyngitis.

• Sore throat, headache, malaise, chills, anorexia, nausea, and high fevers precede erythema of the neck, chest, and axillae that becomes generalized over 4–6 hours.

• The erythema blanches with pressure and is studded with tiny papules (‘sunburn with goose pimples’); the cheeks are also flushed with circumoral pallor.

• Pastia lines (linear petechial streaks) are seen in major body folds, e.g. axillary, inguinal, antecubital.

• Desquamation of distal digits occurs after 7–10 days.

• Postinfectious sequelae include acute glomerulonephritis and rheumatic fever.

• DDx of palmoplantar desquamation: Kawasaki disease, TSS, and any preceding infection (including viral) with a high fever.

• DDx of exanthem: drug eruption, viral exanthem, early SSSS; a scarlatiniform eruption is also seen in TSS and Kawasaki disease.

• Rx: 10- to 14-day course of penicillin or amoxicillin.

BACTEREMIA/SEPTICEMIA

• Septic emboli can present as petechiae and purpura that may develop central pustules or hemorrhagic bullae; subcutaneous abscesses can also be seen.

• Endocarditis can be acute or subacute and caused by organisms including S. aureus and Streptococcus spp., respectively; cutaneous signs of endocarditis include splinter hemorrhages (see Chapter 58), Osler nodes, and Janeway lesions (see Table 18.2).

Gram-Positive Bacilli

Clostridial Skin Infections

• Clostridia spp. are gram-positive bacilli that live on dead organic matter and can cause anaerobic cellulitis or myonecrosis (gas gangrene).

• Anaerobic cellulitis.

– Risk factors: trauma, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, and injection drug use.

– Generally due to Clostridium perfringens > other anaerobic bacteria (e.g. Bacteroides); incubation period >3 days with a rapid course.

– Minimal visible skin changes; signs include crepitus and a thin, dark graybrown, foul-smelling (‘dirty dishwater’) exudate; pain often absent or mild without symptoms of toxemia (e.g. tachycardia).

• Myonecrosis, in contrast to anaerobic cellulitis, has a shorter incubation period with a very rapid course; overlying skin has a dark yellow to bronze discoloration, sometimes with bullae or necrosis, and severe swelling; toxemia (e.g. hypotension) is generally present.

• Rx: early surgical debridement and empirical antibiotics (e.g. clindamycin plus a thirdgeneration cephalosporin) until culture and sensitivities obtained.

Corynebacterium (And Kytococcus) Skin Infections

ERYTHRASMA

• Superficial, localized infection due to Corynebacterium minutissimum.

• Three major clinical variants.

– Interdigital – the most common variant, characterized by chronic maceration with fissuring or scaling; needs to be distinguished from interdigital tinea pedis.

– Intertriginous – thin red-brown plaques in the axillae and groin/upper inner thigh that may be misdiagnosed as tinea cruris (see Table 60.5; Fig. 61.9).

– ‘Disciform’ – often on the trunk and diabetes mellitus is a risk factor (Fig. 61.7D).

• Bright, coral-red fluorescence with Wood’s lamp examination (see Figs. 61.9B and 13.2).

• Rx: topical clindamycin or erythromycin; prevent moisture accumulation with topical aluminum chloride 6–20% (axillae).

PITTED KERATOLYSIS

• Secondary to Kytococcus sedentarius (Micrococcus sedentarius) and Corynebacterium spp.

• Hyperhidrosis, prolonged occlusion, and increased surface pH are contributing factors; the latter plus bacterial infection lead to 1- to 3-mm crater-like depressions in the stratum corneum that may coalesce, with involvement

of soles >> palms (Fig. 61.10).

• Often accompanied by a distinctive malodor.

• Rx: topical clindamycin or erythromycin; decrease eccrine sweat production with topical aluminum chloride 20%.

TRICHOMYCOSIS AXILLARIS

• Common disorder that may be clinically subtle; often accompanied by malodor.

• Hair shafts are ensheathed with adherent yellow > red or black concretions composed of organisms (Fig. 61.11); most common in the axillae and a cause of chromhidrosis (see Chapter 32).

• DDx: other causes of nodules on hair shafts (see Fig. 64.3).

• Rx: shaving of hair; topical antimicrobials (e.g. benzoyl peroxide, erythromycin) can help prevent recurrence.

Other Gram-Positive Skin Infections

ANTHRAX

• Bacillus anthracis causes inhalational, gastrointestinal, and cutaneous disease.

• Occurs most commonly in farmers and ranchers exposed to animals such as sheep, cows, horses, and goats; also secondary to exposure to hides from these animals (e.g. skins used for drums).

• Emerged as an agent of biological terrorism.

• Clinical characteristics of cutaneous disease are outlined in Table 61.4.

• Rx for cutaneous disease: fluoroquinolone (e.g. ciprofloxacin 500 mg PO twice daily) for 60 days.

ERYSIPELOID

• Due to Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae.

• Variants.

– Localized cellulitis – infection due to traumatic inoculation; seen in individuals who prepare fish and meat; the hand is a frequent site of involvement and the color is characteristically redviolet (Fig. 61.12).

– Generalized – uncommon form; multiple pink plaques, usually in the setting of immunosuppression, with associated fever and arthralgias; blood cultures are generally negative.

• DDx of localized form: cellulitis due to more common infectious agents (see above), atypical mycobacterial infection, early Vibrio infection.

• Rx for localized form: penicillin 500 mg PO four times a day for 7–10 days.

Gram-Negative Cocci

ACUTE MENINGOCOCCEMIA

• Systemic infection due to Neisseria meningitides.

• Primarily seen in young children (6 months to 1 year of age) and young adults in close quarters (e.g. dormitories, barracks).

• In most individuals, infection results in an asymptomatic carrier state.

• In acute meningococcemia, one-third to one-half of patients have skin lesions due to septic emboli, initially subtle petechiae that evolve into irregularly shaped purpura with a central gunmetal gray color that reflects necrosis (Fig. 61.13); gram-negative cocci may be seen on Gram staining of lesional tissue.

• The septic lesions are to be distinguished from those due to disseminated intravascular coagulation (see Table 18.1).

• Additional systemic manifestations include fever, chills, hypotension, meningoencephalitis, pneumonia, pericarditis, and myocarditis.

• Rx: IV penicillin or ceftriaxone; vaccination is important for prevention.

CHRONIC MENINGOCOCCEMIA

• An indolent infection due to Neisseria meningitides.

• Recurrent episodes of fever, chills, night sweats, and arthralgias; skin lesions are polymorphous, e.g. pink macules and papules, nodules, petechiae/purpura; the skin lesions represent small vessel vasculitis without visible organisms by light microscopy, but PCR may be used to detect organisms.

GONORRHEA & DISSEMINATED GONOCOCCAL INFECTION

See Chapter 69.

Gram-Negative Bacilli

Pseudomonal Infections

Green nail syndrome is discussed in Chapter 58.

GRAM-NEGATIVE TOE-WEB INFECTION

• Although Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common cause, other gram-negative bacilli can be implicated (e.g. Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis).

• Risk factors are pre-existing tinea pedis and occlusion (e.g. tight-fitting shoes).

• Symptoms of burning and pain; signs include a malodorous exudate with a blue-green tinge, a grape-juice odor, and a moth-eaten appearance of skin due to maceration and erosions (Fig. 61.14).

• In severe cases, there can be cellulitis.

OTITIS EXTERNA (‘SWIMMER’S EAR’)

• Swollen auditory ear canal with greenish purulent discharge.

• Extreme pain with manipulation of the pinna.

• Rx: antimicrobial drops (e.g. ofloxacin) with or without an ear wick, oral analgesics (e.g. NSAIDs).

PSEUDOMONAL FOLLICULITIS (HOT TUB FOLLICULITIS)

See Table 31.2.

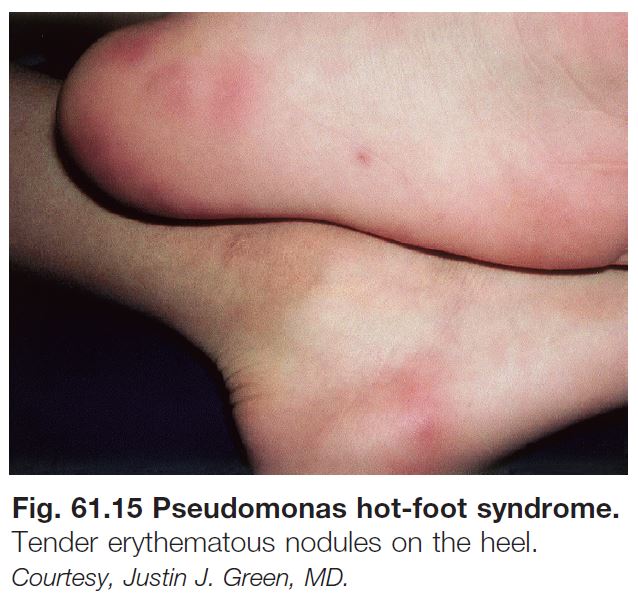

PSEUDOMONAS HOT-FOOT SYNDROME

• Develops acutely on the soles of children and adolescents who are otherwise healthy after swimming in water with high concentrations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

• Painful and tender, red-purple, 1- or 2-cm nodules appear on the weight-bearing aspects of the feet (Fig. 61.15).

• Self-limiting and DDx is primarily idiopathic palmoplantar hidradenitis (Chapter 32).

CELLULITIS

• Clinical features are similar to those of cellulitis due to S. aureus (see above); can occur on the lower extremity in the setting of gram-negative toe-web infection or on the external ear postoperatively.

• Sometimes, it can be difficult to distinguish soft tissue infection from colonization with Pseudomonas, particularly in chronic ulcers.

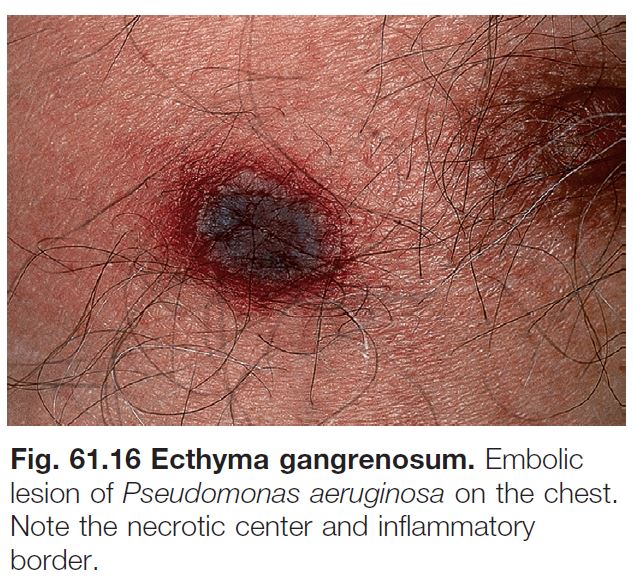

ECTHYMA GANGRENOSUM

• A sign of bacteremia or septicemia.

• Most commonly due to gram-negative bacilli, including Pseudomonas, but can also be due to opportunistic fungi; primarily seen in immunocompromised hosts, especially those with prolonged neutropenia.

• A red-purple macule or patch that develops central necrosis; sometimes the necrosis is preceded by a hemorrhagic bulla; the number can vary from one to a dozen or more (Fig. 61.16).

• The most common location for ecthyma gangrenosum due to Pseudomonas is the groin.

• To establish the diagnosis, culture of tissue, obtained via sterile biopsy technique (see Fig. 2.10), is performed in combination with histopathology.

TREATMENT OF PSEUDOMONAL INFECTIONS

• For superficial infection (e.g. gram-negative toe-web infection): 5% acetic acid soaks followed by application of a topical antibiotic (e.g. gentamicin, silver sulfadiazine); if minimal improvement or severe, oral fluoroquinolone.

• For severe or systemic infections: piperacillin/ tazobactam or doripenem if penicillin-allergic; may be combined with an aminoglycoside antibiotic.

Diseases Caused by Bartonella Species

See Table 61.5.

Other Gram-Negative Skin Infections with Fever and Skin Findings

See Table 61.6.

Spirochetes

LYME DISEASE

See Chapter 15.

SYPHILIS

See Chapter 69.

OTHER TREPONEMAL DISEASES

• Like syphilis, other treponemal diseases may have primary, secondary, and tertiary stages.

• Endemic syphilis.

– Due to Treponema pallidum endemicum.

– Seen most commonly in Africa, the Arabian peninsula, and Southeast Asia.

– Children younger than the age of 15 years are most often affected.

– Primary lesion often missed.

– Secondary stage: macerated patches on lips, tongue, and pharynx; angular stomatitis; condyloma lata; generalized lymphadenopathy.

– Tertiary stage: gummas that can lead to destruction of the palate and nasal septum.

• Pinta.

– Due to T. carateum.

– Seen primarily in Central and South America.

– Primary stage: minute macules or papules with erythematous haloes, most commonly on the lower extremities, that develop into infiltrated plaques over several months.

– Secondary stage: smaller, variably pigmented (red, blue, black, or hypopigmented), scaly macules and papules that may coalesce; clustered near the initial primary lesion or generalized.

– Tertiary stage: symmetric, depigmented, vitiligo-like lesions that are atrophic or keratotic.

• Yaws.

– Due to T. pallidum pertenue. – Seen in warm, humid, tropical climates.

– Children younger than the age of 15 years are most often affected.

– Primary: erythematous, infiltrated, painful papule, usually on the extremities; enlarges to become up to 5 cm in diameter and ulcerates; heals spontaneously over 3–6 months.

– Secondary: smaller lesions adjacent to orifices or adjacent to site of initial primary lesion (Fig. 61.17).

– Tertiary: destructive skin lesions, palmoplantar thickening that can lead to difficulty with ambulation, chronic osteitis (sabre tibia).

Filamentous Bacteria

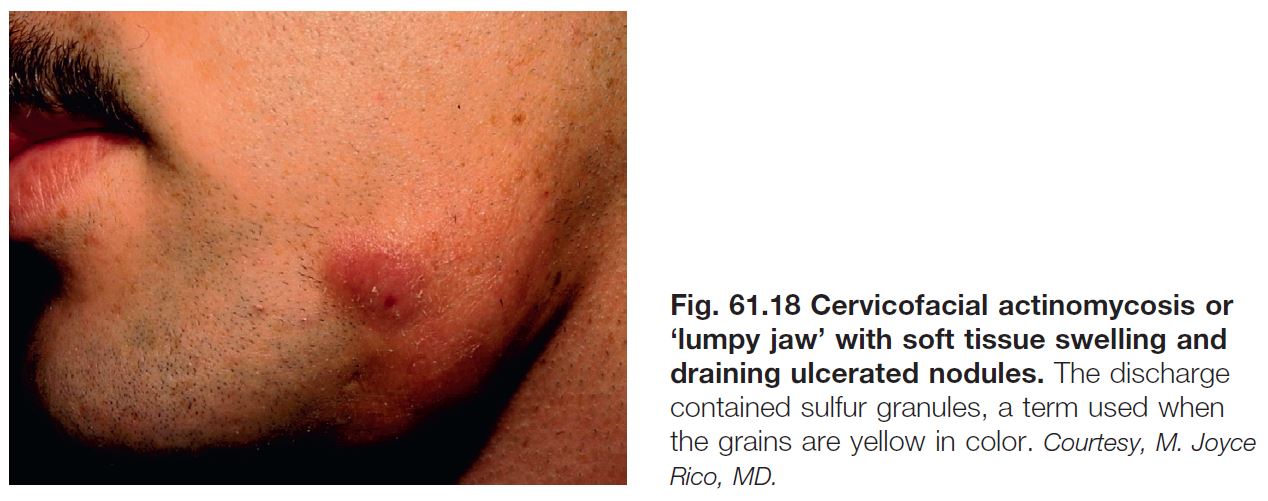

ACTINOMYCOSIS

• Most commonly due to Actinomyces israelii.

• Three major sites of involvement – cervical, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal.

• Skin involvement is most common with the cervical variant and is sometimes referred to as ‘lumpy jaw’ due to irregular subcutaneous nodules; the latter can drain and the exudate contains grains (Fig. 61.18).

• Rx: penicillin.

ACTINOMYCOTIC MYCETOMA

• Most commonly due to Nocardia as well as Actinomadura madurae, Actinomadura pelletieri, and Streptomyces somaliensis; organisms are found in soil and on plant material (Table 61.7).

• DDx: distinguishing this entity from eumycotic mycetoma requires culture of grains or tissue; prior to the return of tissue or grain culture results, a presumptive diagnosis can be made based on the diameter of the filaments or hyphae composing the grains in biopsy specimens.

NOCARDIOSIS

See Table 61.7.

Preauth

Preauth