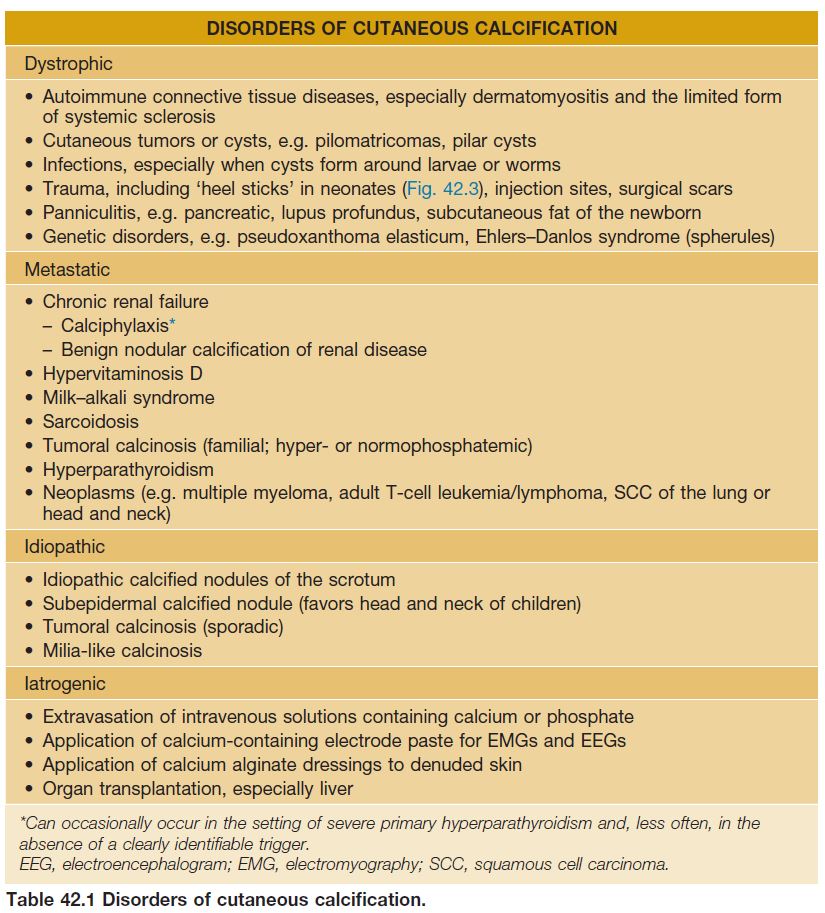

There are four major forms of cutaneous calcification (calcinosis cutis): (1) dystrophic – locally within sites of pre-existing skin damage; (2) metastatic – due to systemic metabolic derangements; (3) iatrogenic – secondary to medical treatment or testing; and (4) idiopathic. Cutaneous ossification (osteoma cutis) occurs in the setting of several genetic disorders, in a miliary form on the face and within neoplasms and sites of inflammation (secondary).

Calcinosis Cutis

• Deposition of amorphous, insoluble calcium salts within the skin.

Calcinosis Cutis – Dystrophic

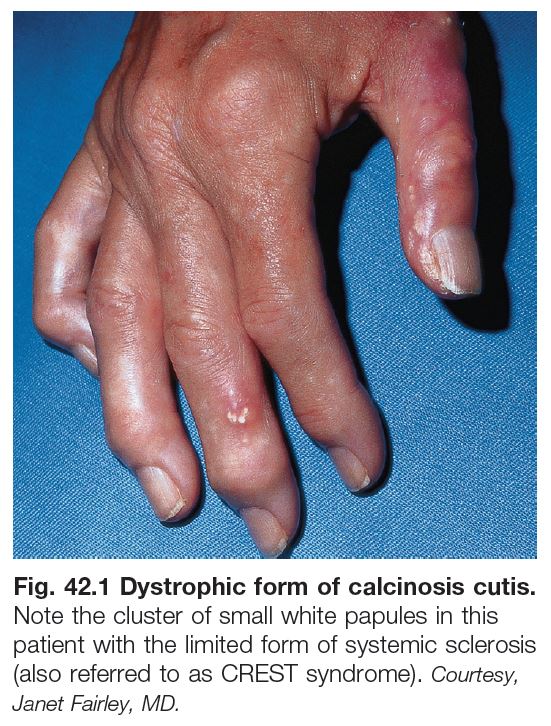

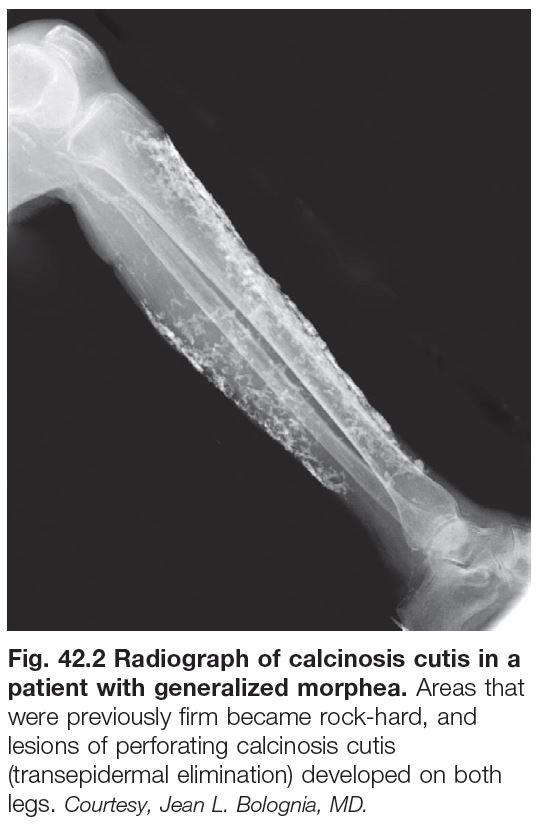

• Often seen in autoimmune connective tissue diseases (AI-CTDs), in particular the limited form of systemic sclerosis (also referred to as CREST syndrome) and childhood dermatomyositis (Figs. 42.1 and 42.2); in the former, hard, skin-colored to white papules overlie the bony prominences of the extremities (upper > lower), whereas in the latter the deposits are often larger and sometimes plate-like.

• Extrusion (transepidermal elimination or ‘perforation’; see Ch. 79) of the calcium deposits appears as a white chalky material and it can be followed by a persistent ulceration.

• Other underlying causes are listed in Table 42.1.

• Rx: aggressive treatment of AI-CTDs, when possible, prior to the appearance of calcinosis cutis; excision of symptomatic localized deposits, if feasible; sodium thiosulfate and calcium channel blockers, e.g. diltiazem, may be effective in some patients.

Calcinosis Cutis – Metastatic

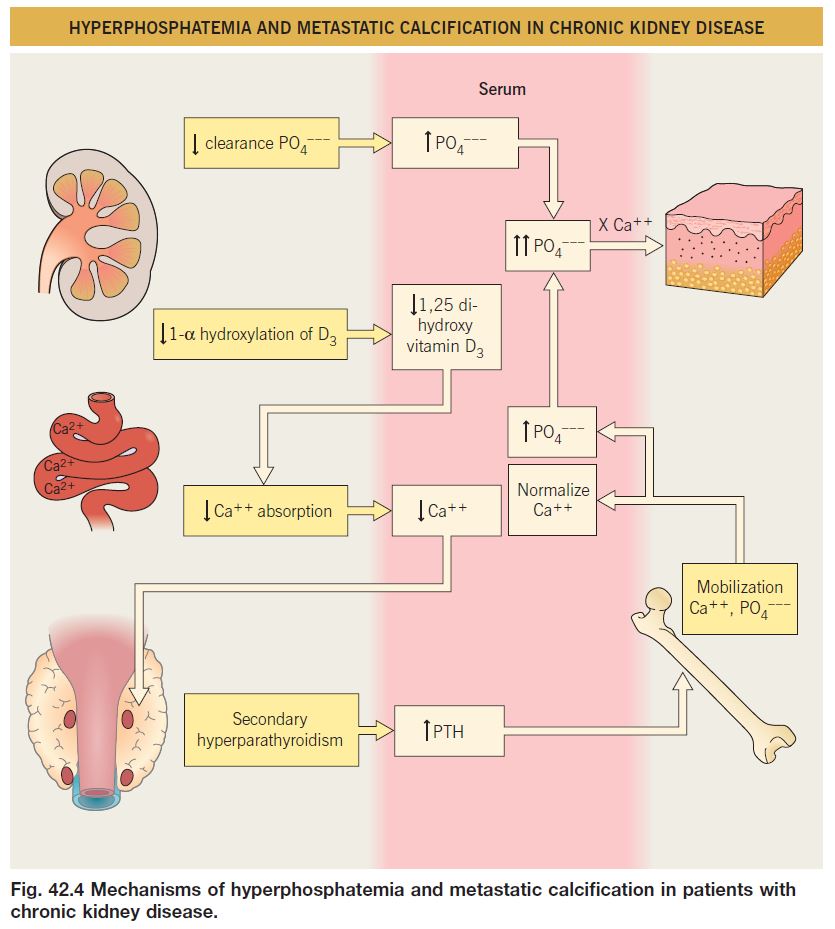

• The most common cause is end-stage renal disease with its associated hyperphosphatemia and decreased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D levels (Fig. 42.4).

• The two major presentations in patients with chronic kidney disease are: (1) benign nodular calcification in which deposits occur within otherwise normal skin, especially around joints; and (2) calciphylaxis, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

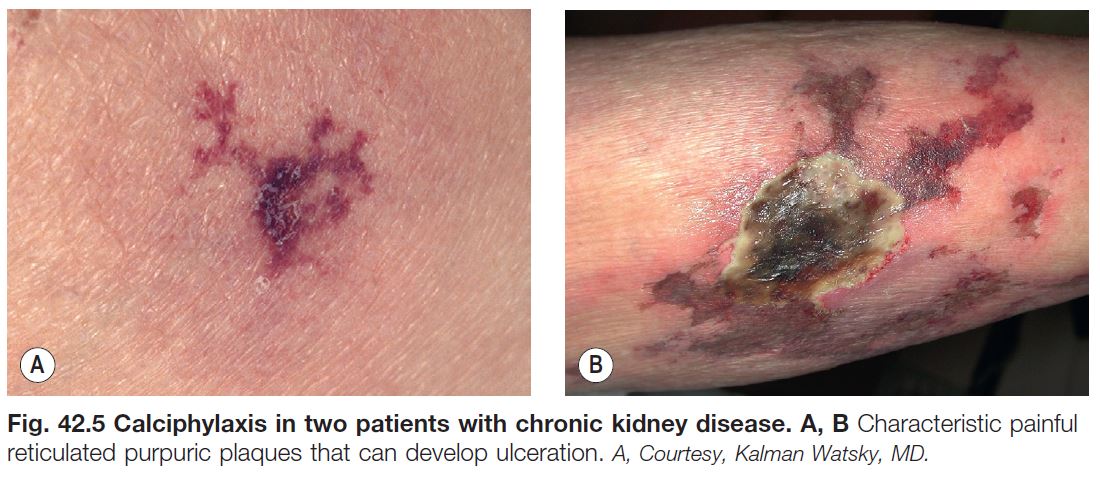

• Calciphylaxis is characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis which presents as markedly painful retiform purpura and ulcerations (Fig. 42.5); risk factors include obesity and hypercoagulability (e.g. protein C dysfunction); deposits of calcium within blood vessel walls of the subcutis are usually present, but not always, presumably due to sampling error.

• Other etiologies are listed in Table 42.1.

• Rx of calciphylaxis is difficult but includes aggressive wound care and normalization of the Ca++–PO4 – – – product via the use of phosphate binders and sometimes parathyroidectomy; drugs such as sodium

thiosulfate and cinacalcet can also be tried as well as local injections of sodium thiosulfate.

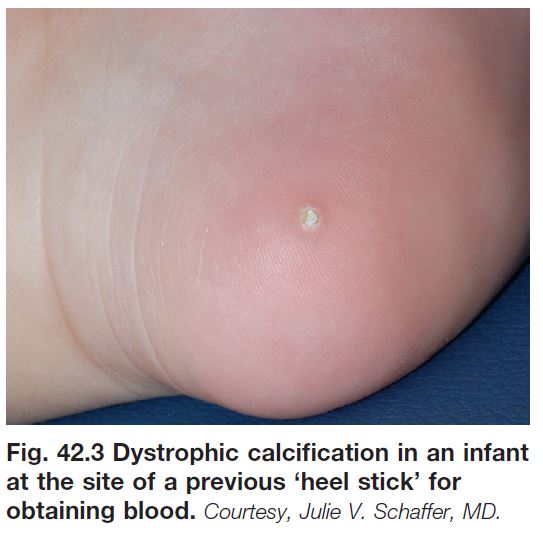

Calcinosis Cutis – Iatrogenic and Idiopathic

• Iatrogenic causes and idiopathic forms are listed in Table 42.1.

• Calcification of epidermoid inclusion cysts is the major cause of calcified nodules of the scrotum.

• Rx: if symptomatic and feasible, surgical excision.

Osteoma Cutis

• Deposition of a protein matrix plus hydroxyapatite (Ca++, PO4 – – –) within the skin.

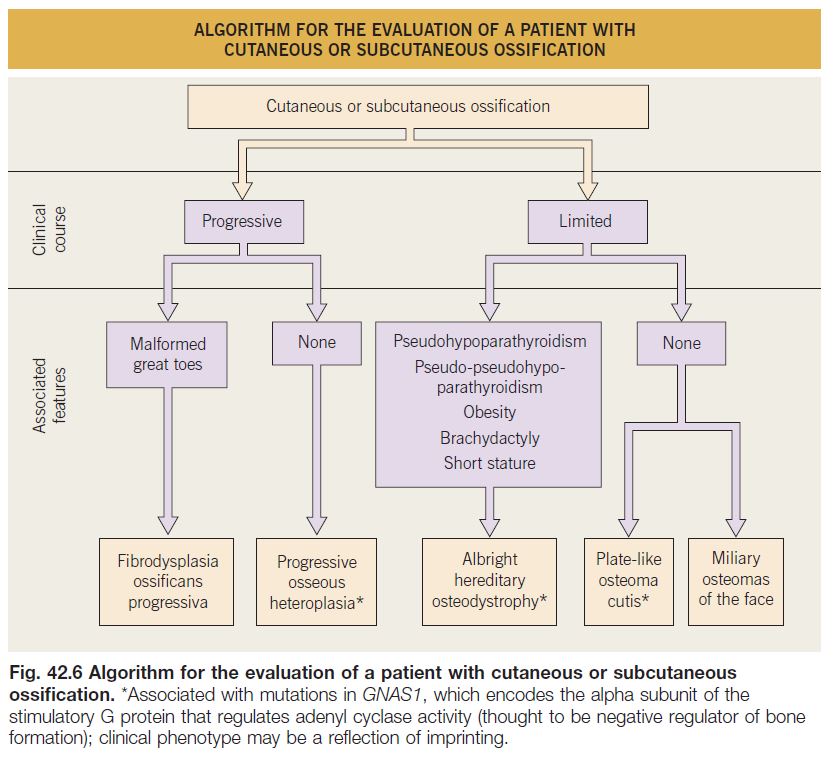

• The four genetic disorders that often have cutaneous or subcutaneous ossification are outlined in Fig. 42.6.

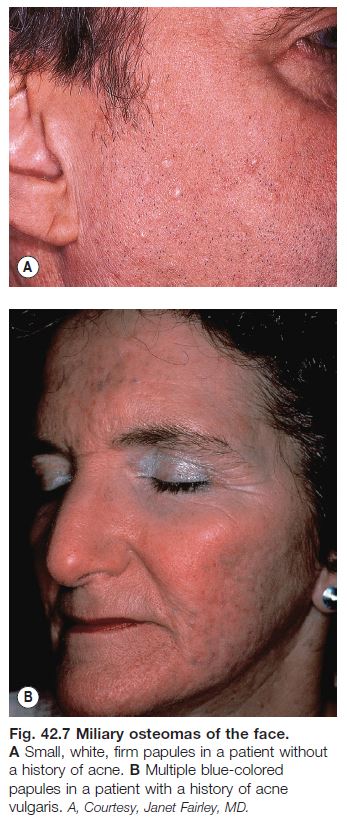

• Miliary osteomas of the face is a rather common entity; small hard papules, whose color can vary from white or skin-colored to blue (Fig. 42.7), gradually appear on the face of adult women > men; the role of pre-existing acne vulgaris and its treatment with oral antibiotics is debated.

• Ossification can also occur within cysts and tumors (e.g. pilomatricomas, melanocytic nevi) as well as at sites of inflammation; it is often preceded by cutaneous calcification.

• Rx: if symptomatic and feasible, surgical excision.

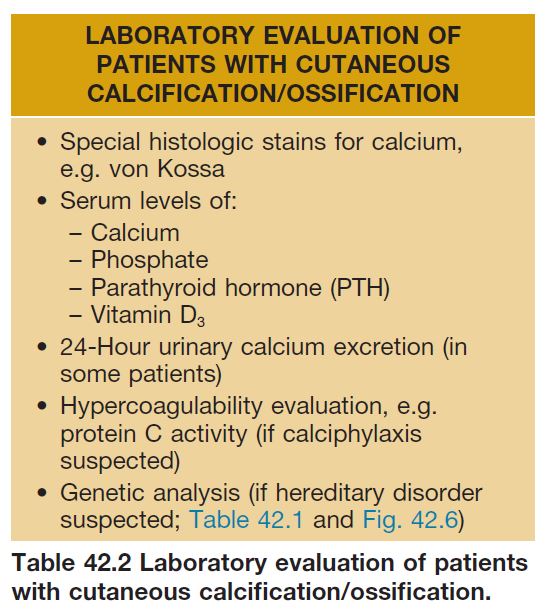

The evaluation of a patient with calcinosis cutis or osteoma cutis is outlined in Table 42.2.

Preauth

Preauth