Key Points

• Cutaneous fungal diseases can be broadly divided into two groups:

– Superficial – limited to the stratum corneum, hair, and/or nails.

– Deep – dermal and/or subcutaneous.

• Superficial fungal infections can be further subdivided into:

– Noninflammatory – most commonly tinea versicolor, but includes tinea nigra and piedra.

– Inflammatory – primarily infections due to dermatophytes (Trichophyton, Microsporum, Epidermophyton; e.g. tinea corporis, tinea cruris) or Candida spp. (e.g. cutaneous candidiasis of the groin).

• Deep fungal infections are often secondary to implantation (e.g. sporotrichosis, chromoblastomycosis, eumycetoma) or hematogenous spread of an underlying systemic infection (e.g. cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis).

• Opportunistic pathogens (e.g. Aspergillus, Mucor) can lead to systemic infection in immunosuppressed hosts.

Superficial Fungal Infections

Tinea (Pityriasis) Versicolor

• Secondary to transformation of Malassezia spp., especially M. furfur, from the yeast form to the hyphal form (see Fig. 2.1A).

• Malassezia spp. are part of the normal flora.

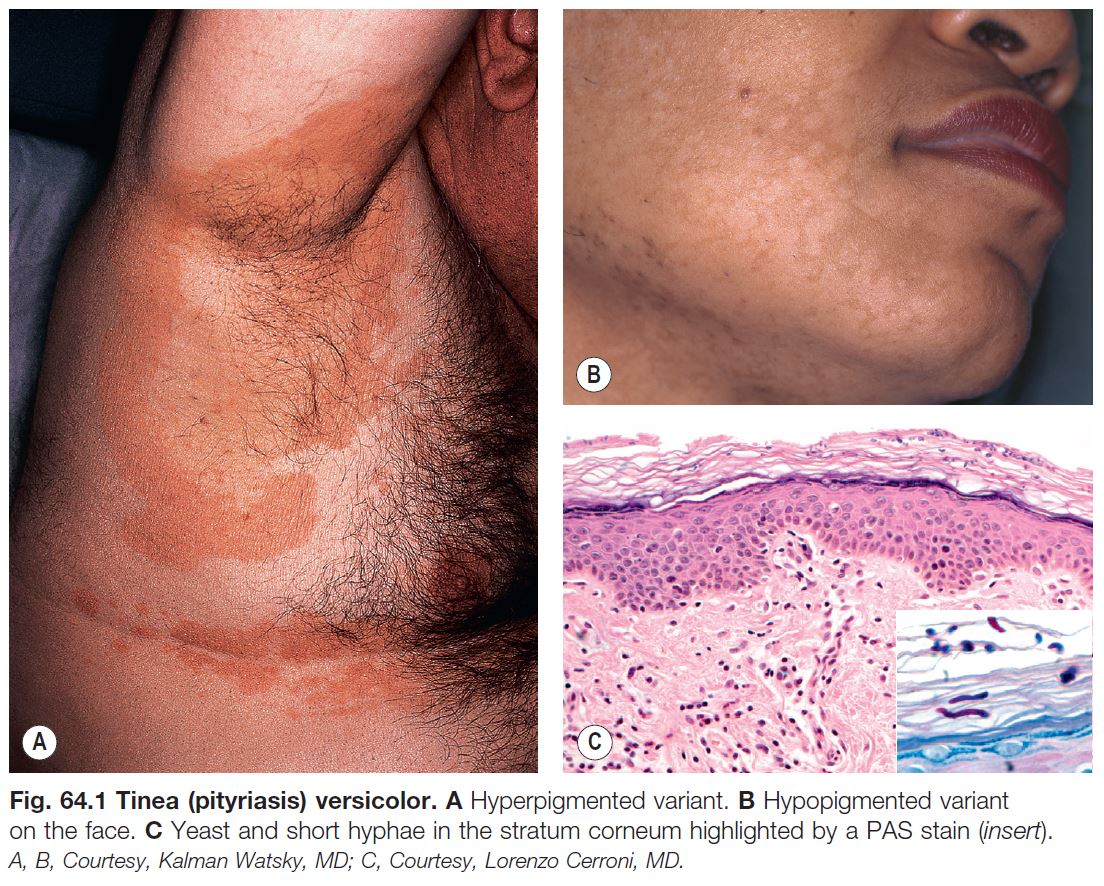

• Multiple, brown (hyperpigmented), tan (hypopigmented), or pink, oval to round macules, patches, or thin plaques; there is often coalescence of lesions centrally with scattered lesions at the periphery.

• Associated scale may be subtle but becomes more obvious with gentle scratching or stretching of the skin.

• Most commonly develops on the upper trunk and shoulders, but can also involve flexural sites such as the antecubital fossae, submammary folds, and groin (Fig. 64.1); in children more frequently than adults, there can also be facial involvement.

• Often first noticed in the summer, and a suntan accentuates the hypopigmented variant.

• DDx: postinflammatory hypopigmentation and idiopathic macular hypomelanosis (if hypopigmented); confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud (if hyperpigmented; see Chapter 89).

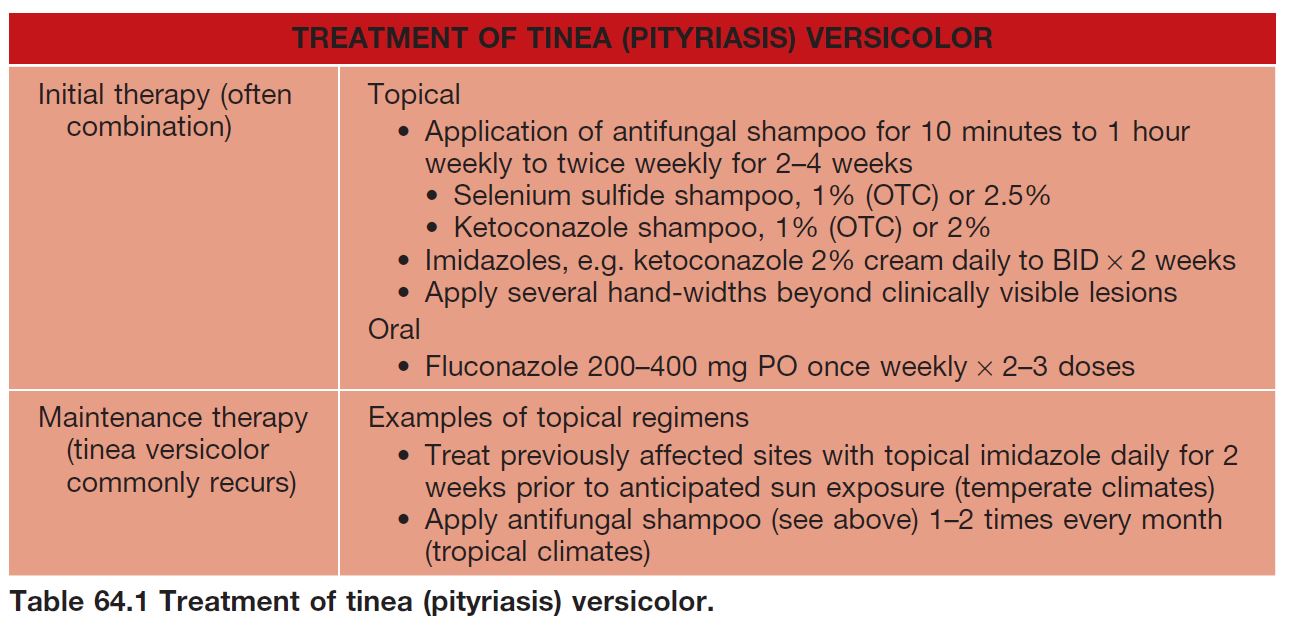

• Rx: outlined in Table 64.1.

• Following appropriate Rx, the associated hypopigmentation may persist for months until there is repigmentation or fading of the suntan.

Tinea Nigra, Black Piedra, and White Piedra

• Typically seen in tropical areas.

• Tinea nigra.

– Most commonly due to infection with Hortaea werneckii, a pigmented fungus found in soil.

– Brown, sharply marginated macule or patch; most commonly on the palms (Fig. 64.2).

– Rx: keratolytic agents (e.g. salicylic acid 6% cream) and topical antifungals (e.g. terbinafine 1% cream).

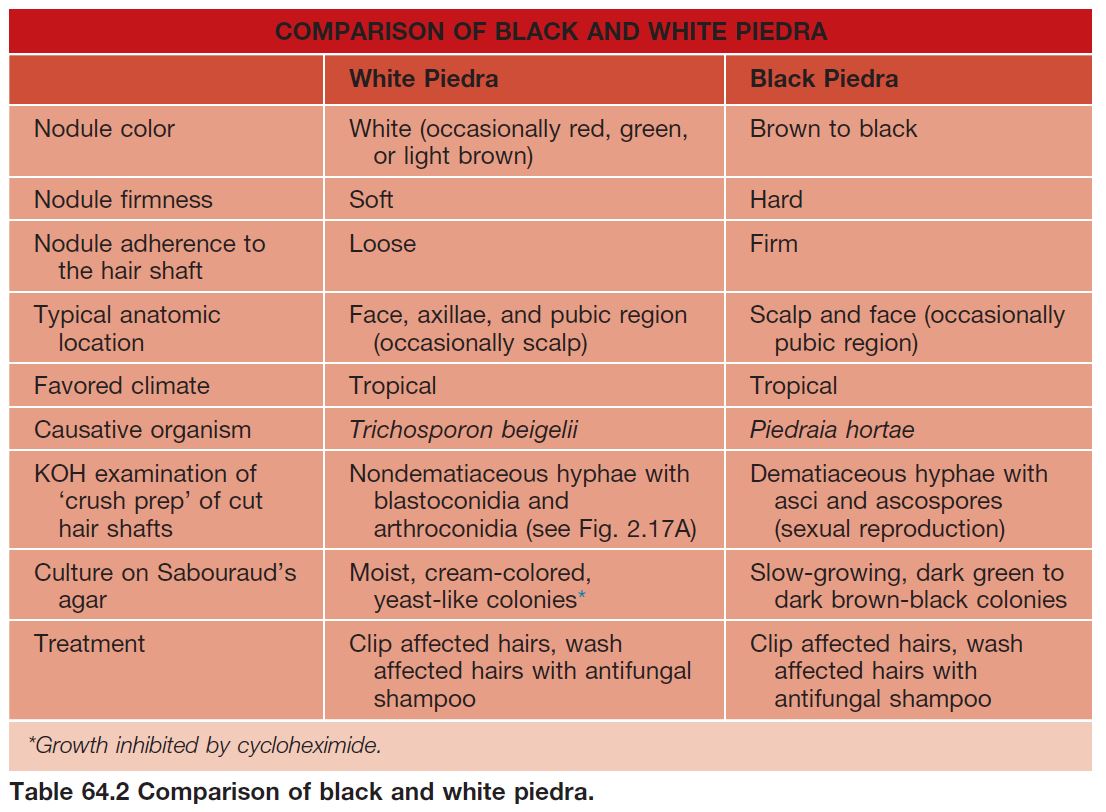

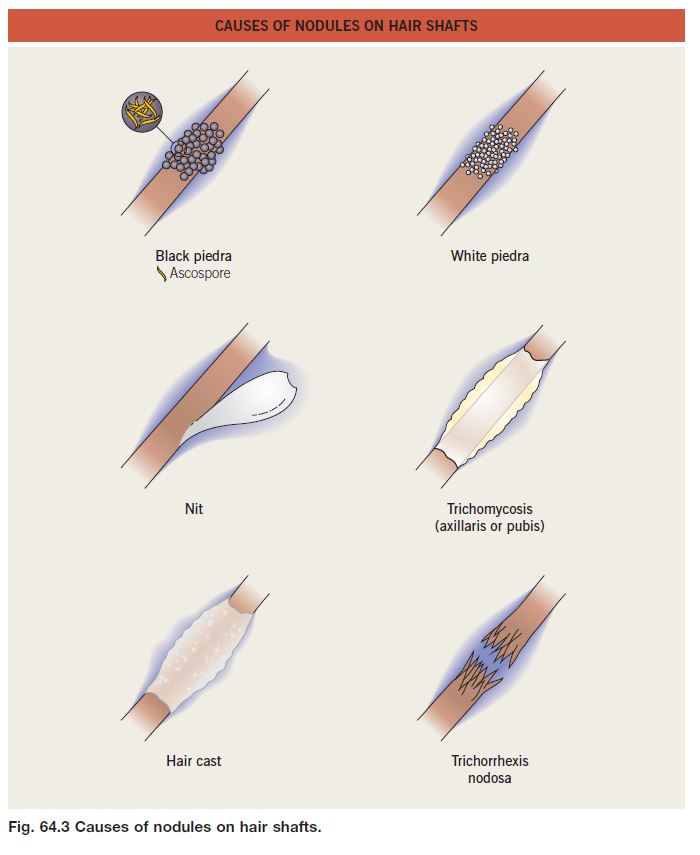

• Black piedra and white piedra are characterized by the formation of nodules on hair shafts (Table 64.2; Fig. 64.3).

Dermatophytoses (Tinea Infections)

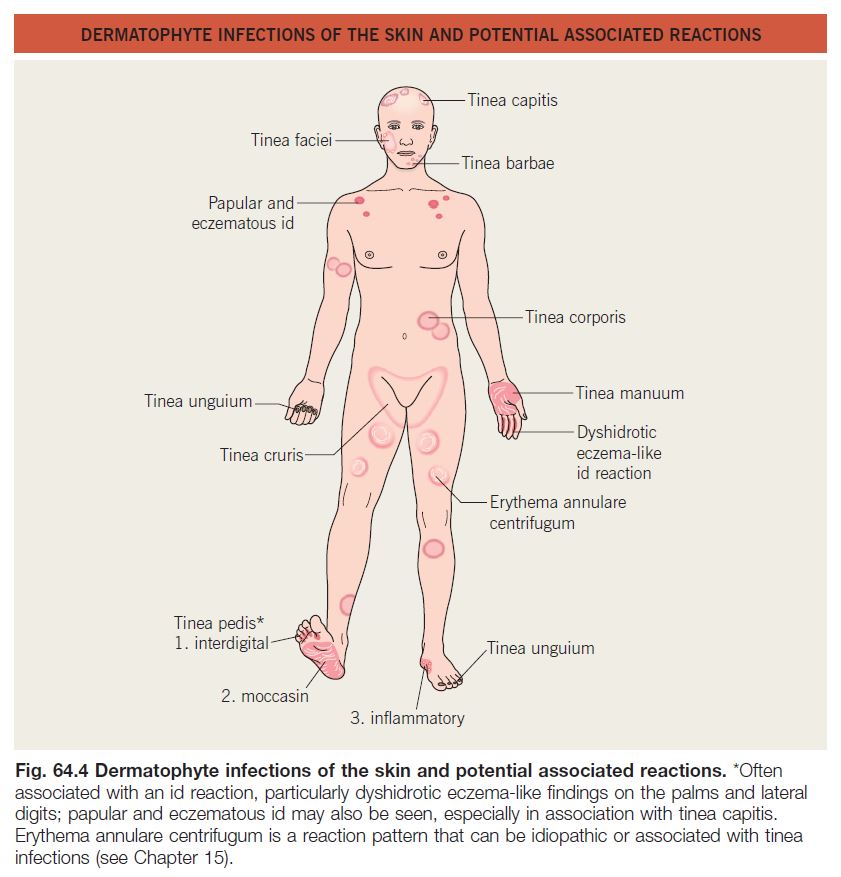

• The names of dermatophyte infections consist of the word ‘tinea’ followed by the Latin name for the involved body site; examples are tinea pedis (foot) and tinea cruris (groin) (Fig. 64.4).

• Due to fungi of three genera – Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton – that invade only keratinized tissue (stratum corneum, hair, and nails).

– With the exception of tinea capitis, Trichophyton rubrum and T. mentagrophytes are the most common pathogens.

– Trichophyton mentagrophytes has two major variants that infect the skin, which can lead to confusion; T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale is spread human-to-human, whereas T. mentagrophytes var. mentagrophytes is acquired from animals; these variants are also known as T. interdigitale [anthropophilic] and [zoophilic], respectively.

• Transmission occurs via close contact with infected humans or domestic animals, occupational or recreational exposure (e.g. locker rooms), and contact with contaminated clothing, furniture, or brushes; the latter inanimate objects serve as fomites.

• More commonly seen in adults, with the exception of tinea capitis, which occurs more often in children.

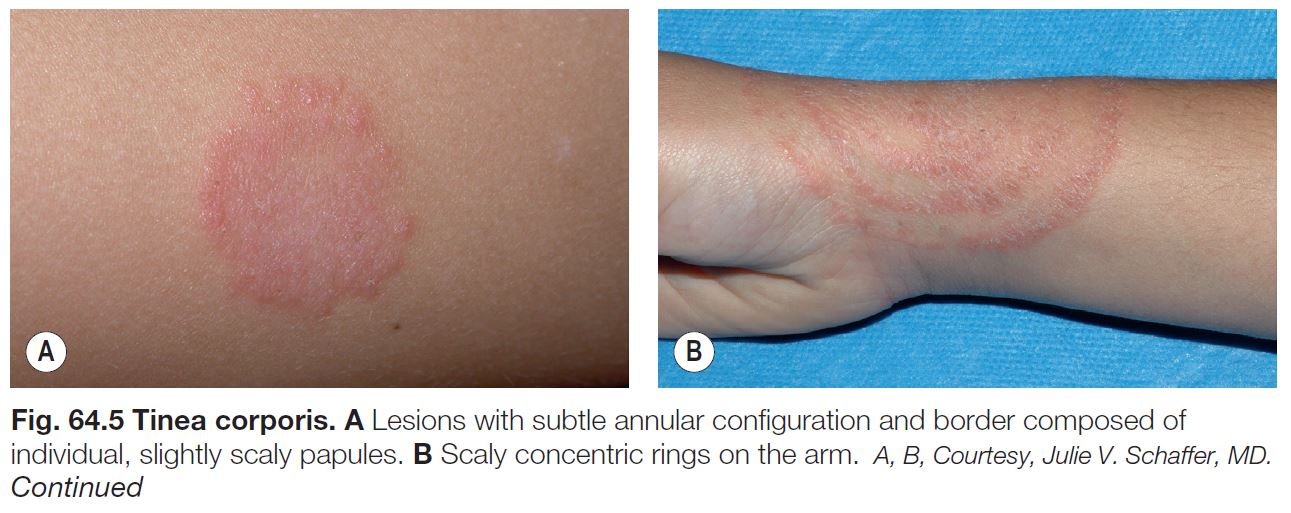

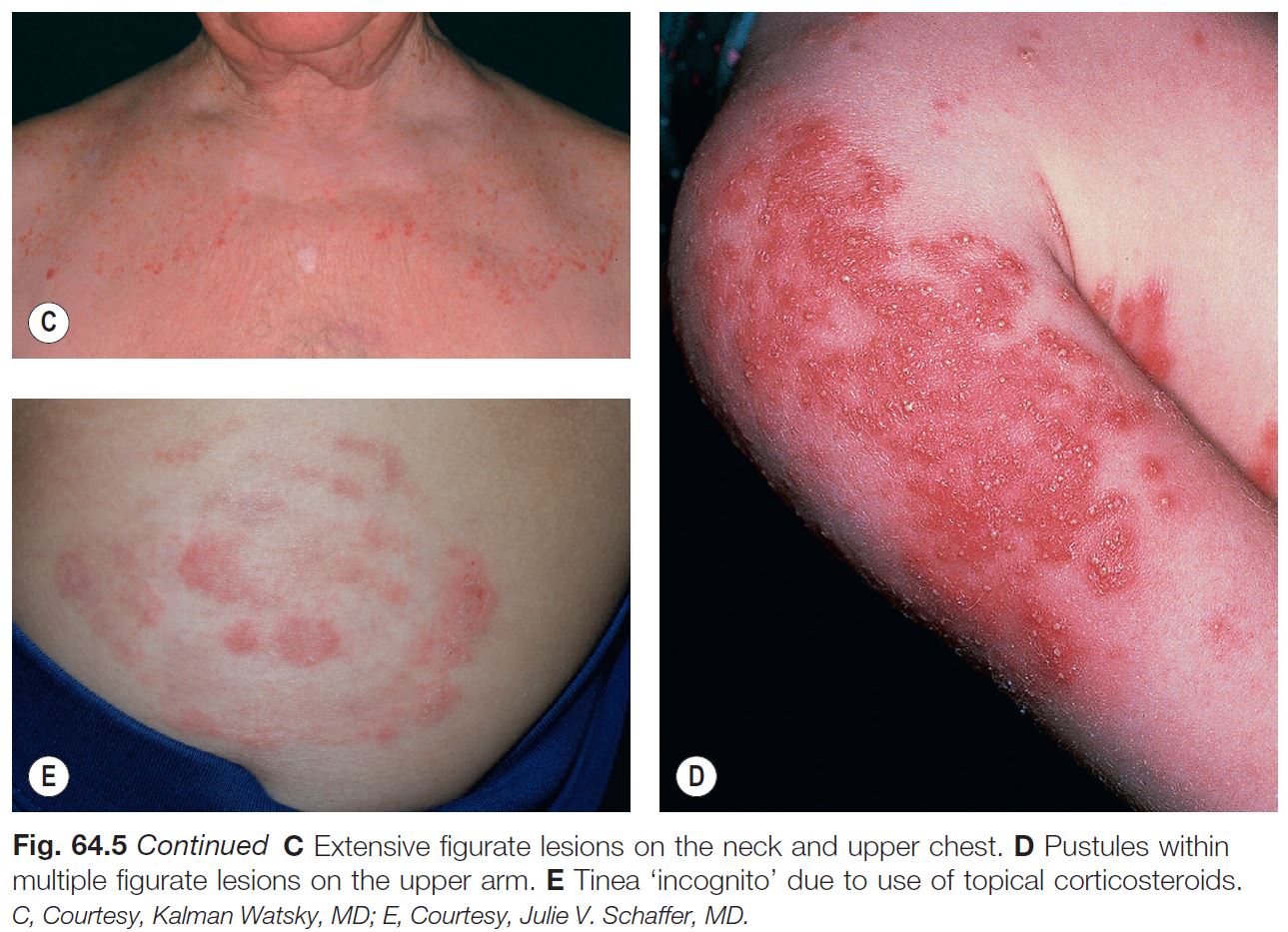

• The classic presentation is an erythematous, annular lesion with an active, scaly border; superficial pustules may also be present (Fig. 64.5).

• Occasionally, vesicles may develop, especially in tinea pedis or manuum due to T. mentagrophytes.

• Dx: KOH ± fungal culture of skin scrapings (see Fig. 2.1) as well as hairs and nails, in the case of tinea capitis and tinea unguium, respectively.

• Important variants:

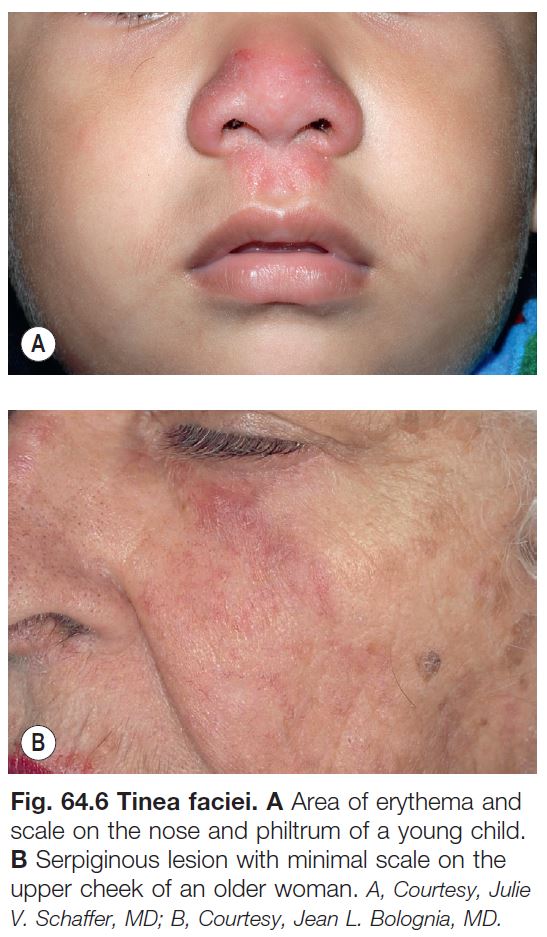

– Tinea incognito refers to atypical clinical presentations, often due to inappropriate treatment with potent topical CS or combination topical therapies that contain CS; lesions may lack scale or be minimally inflamed (Fig. 64.6; see Fig. 64.5E).

– Majocchi’s granuloma is characterized by erythematous papules or pustules within an area of tinea corporis; the papules represent sites of hair shaft invasion, usually due to T. rubrum; often seen in women with tinea pedis who shave their legs or in immunosuppressed patients (see Fig. 31.4A; Fig. 64.7).

Examples of Specific Types of Dermatophytoses

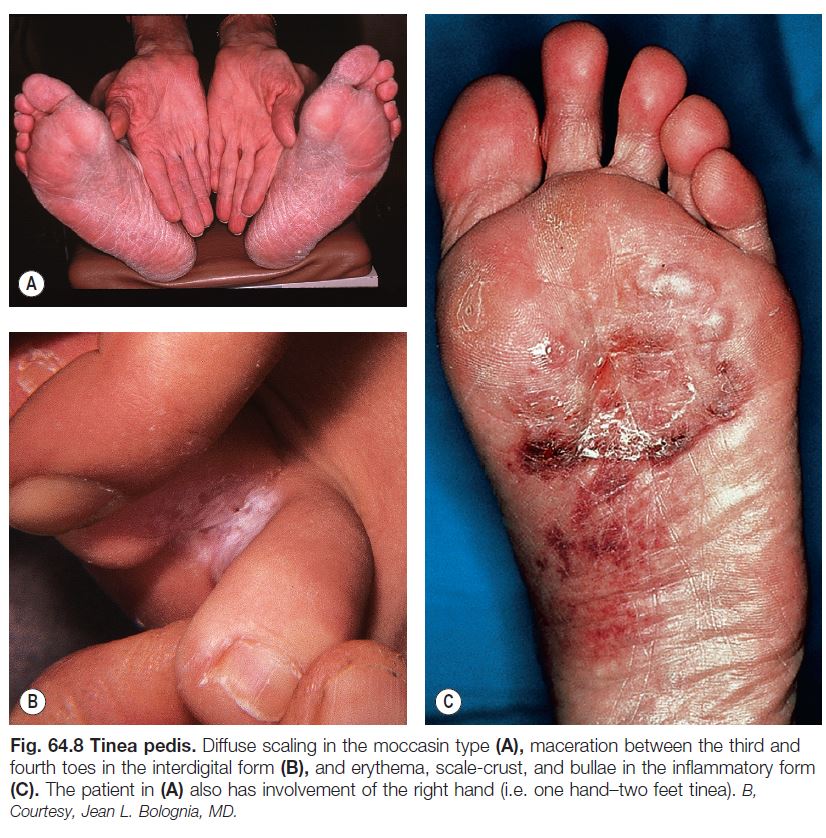

• Tinea pedis (Fig. 64.8).

– Most commonly due to T. rubrum or T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale > Epidermophyton floccosum.

– Three major types: (1) interdigital – erythema, scaling, and maceration in the web spaces, especially the two lateral web spaces, which have the most occlusion; can be accompanied by fissures as well as superimposed bacterial infection; (2) moccasin – diffuse scaling and erythema that extends onto the lateral aspect of the feet; and (3) inflammatory (vesicular) – vesicles and bullae, especially on the medial aspect of the plantar surface.

– Occasionally, especially in immunocompromised and diabetic patients, a more severe ulcerative toe-web infection can occur where there is both a dermatophyte and a bacterial (e.g. pseudomonal) infection; see discussion of gram-negative toe-web infection in Chapter 61.

– Consider use of oral antifungal medications if the tinea pedis fails to respond to topical agents or is severe (Table 64.3).

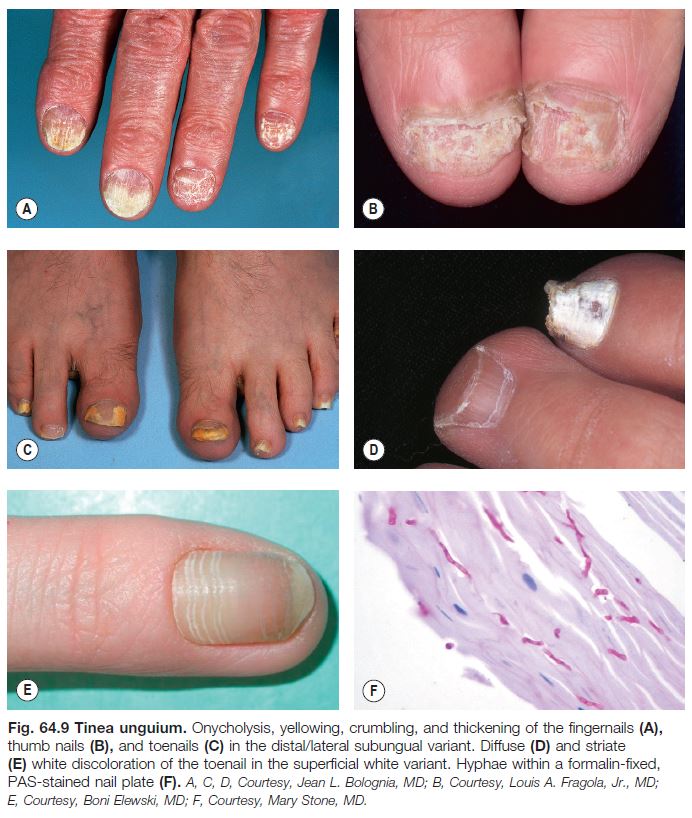

• Tinea unguium (Fig. 64.9).

– Dx: KOH preparation and/or fungal culture of nail plate and subungual scale, PAS-staining of nail clippings.

– Of note, onychomycosis is a more general term that includes nail infections due to dermatophytes, Candida spp., and saprophytes (up to 10% of toenail infections; Table 64.4).

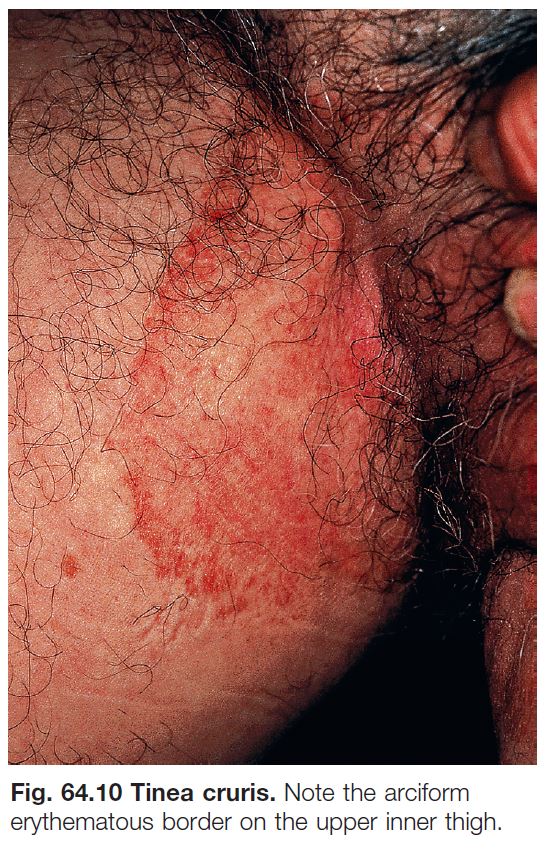

• Tinea cruris (Fig. 64.10).

– Favors the upper inner thighs and can extend to the lower abdomen and buttocks; associated with tinea pedis.

– Most commonly due to T. rubrum > Epidermophyton floccosum > T. mentagrophytes var. interdigitale.

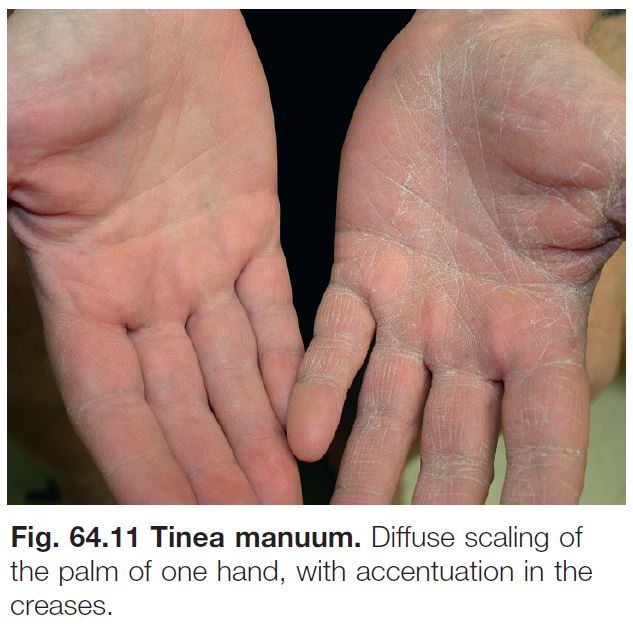

• Tinea manuum (Fig. 64.11).

• Often due to same dermatophyte as associated tinea pedis.

• Can be unilateral (‘one hand, two feet syndrome’; see Fig. 64.8A).

• Tinea unguium of the involved hand is a clinical clue.

• Tinea faciei (see Fig. 64.6).

– Misdiagnosis is common and application of topical CS is a typical history, often leading to tinea incognito.

– An arciform shape with pustules in the border points to the diagnosis.

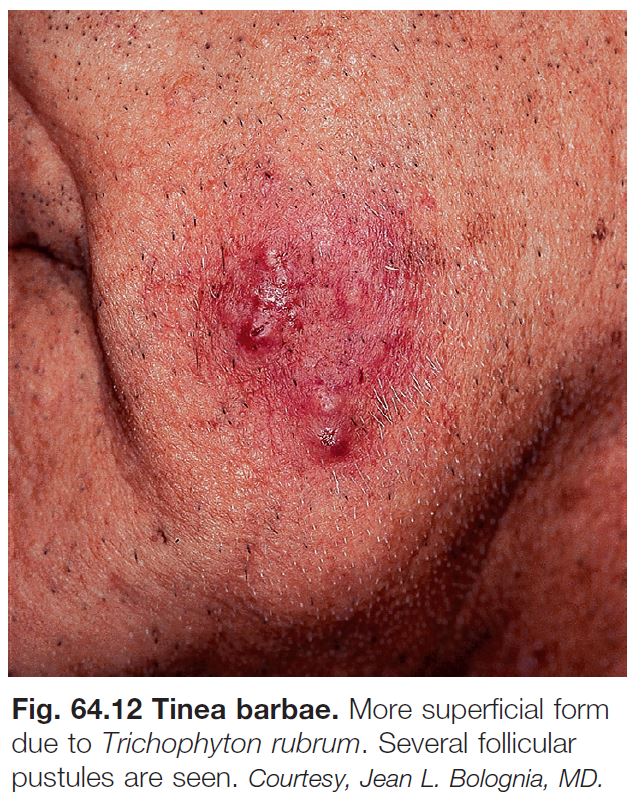

• Tinea barbae (Fig. 64.12; see Fig. 31.7).

– Often secondary to a zoophilic dermatophyte – i.e. acquired from an animal, e.g. T. mentagrophytes var. mentagrophytes (small mammals) and T. verrucosum (cattle).

– Favors postpubertal males.

– Invasion of hair shafts and intense inflammation with follicular pustules and abscess formation; can resemble a kerion.

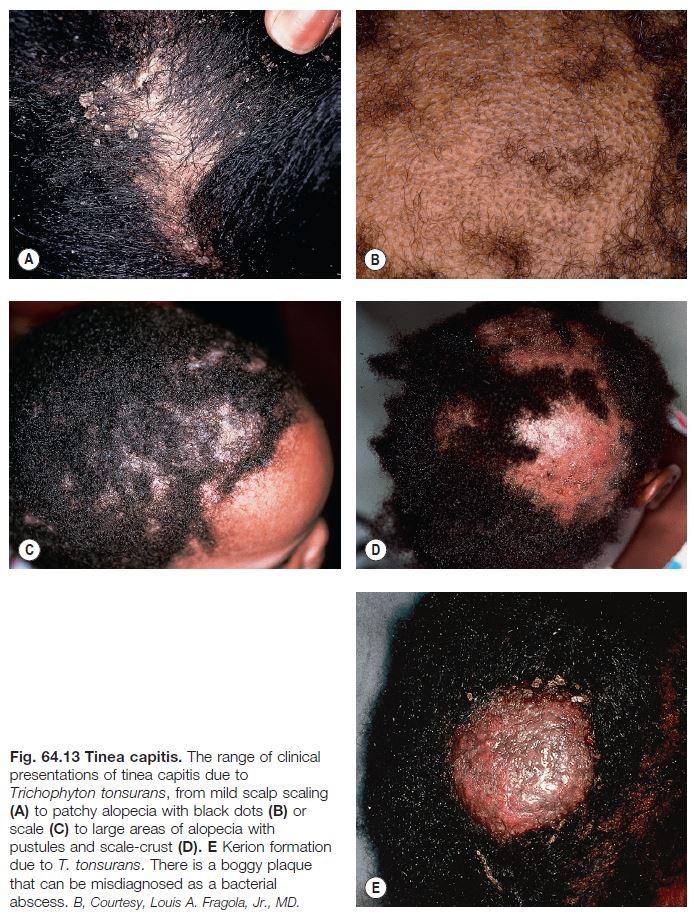

• Tinea capitis (Fig. 64.13).

– Occurs more frequently in children.

– In the United States as well as other regions such as the United Kingdom, T. tonsurans is the most common pathogen; for example, in the United States, it causes >95% of tinea capitis; T. tonsurans primarily affects those with afrocentric hair.

– Tinea capitis due to T. tonsurans can be more difficult to diagnose because the clinical findings may be subtle with only seborrheic dermatitis-like scaling of the scalp, minimal alopecia, and no fluorescence by Wood’s lamp examination (in contrast to ectothrix infection due to M. canis).

– Multiple spores (conidia) within or surrounding hair shafts, referred to as endothrix or ectothrix tinea capitis, respectively, cause fragility and breakage of hair, leading to areas of alopecia (see Figs. 2.2 and 2.3).

– In addition to alopecia, clinical clues include pustules, scale, and crusting; occasionally, there is formation of a kerion (see Fig. 64.13E) or development of posterior cervical and posterior auricular lymphadenopathy.

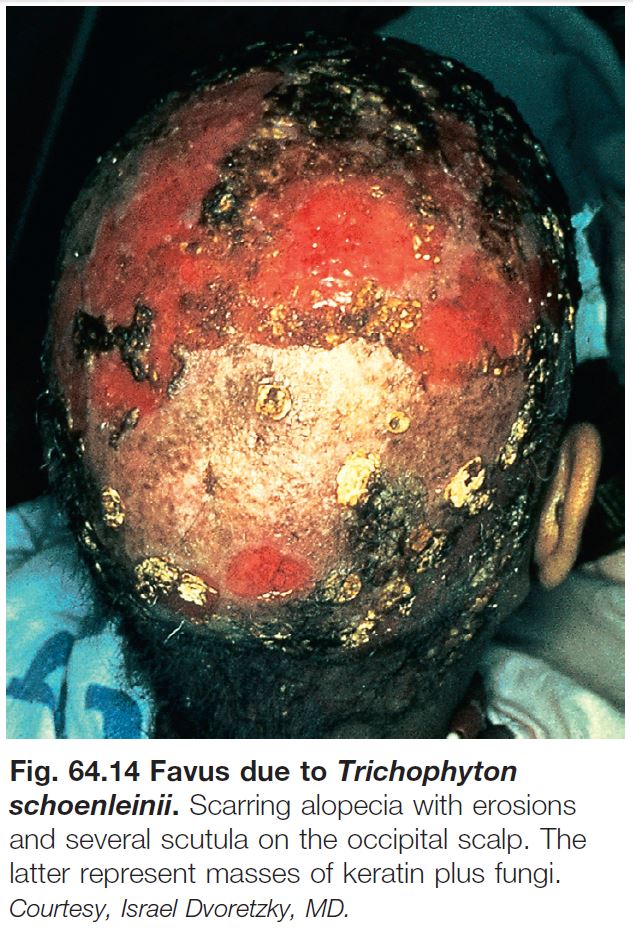

– A type of tinea capitis seen in the Mediterranean basin and Middle East is favus, in which there are keratotic masses that contain hyphae and keratin (Fig. 64.14).

– Rx: oral treatment is required; for children, an adequate dose of griseofulvin is 20–25 mg/kg/day (microsized suspension) × 6–8 weeks; combination therapy with 2.5% selenium sulfide or 2% ketoconazole shampoo is recommended to kill spores and reduce transmission; see Table 64.3 for additional oral therapies.

• Id reactions (see Chapter 11) can occur in the setting of dermatophyte infections; two of the more common examples are as follows (see Fig. 64.4):

– Dyshidrotic eczema-like papules and vesicles of the palms and fingers seen in association with tinea pedis.

– Pruritic papules favoring the upper trunk in the setting of tinea capitis, often following the initiation of appropriate

therapy.

• Erythema annulare centrifugum may also be present in association with tinea pedis (see Chapter 15 and Fig. 64.4).

• DDx: outlined in Table 64.4.

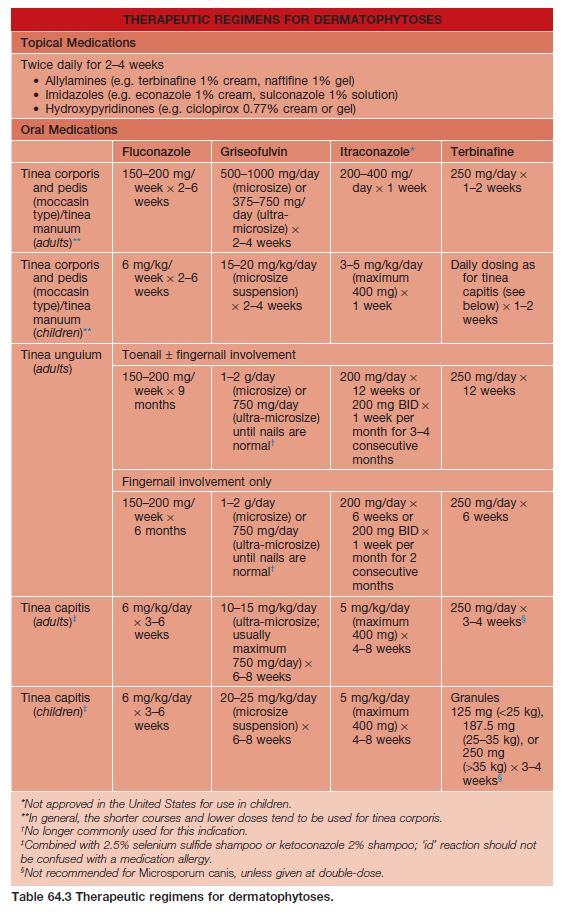

• Rx: outlined in Table 64.3.

Superficial Mucocutaneous Candida Infections

• Most commonly due to Candida albicans or C. tropicalis.

• Wide spectrum of clinical presentations, from diaper dermatitis in infants (see Fig. 13.4) to intertrigo (see Table 60.5 and Fig. 13.2) to chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (see Chapter 49).

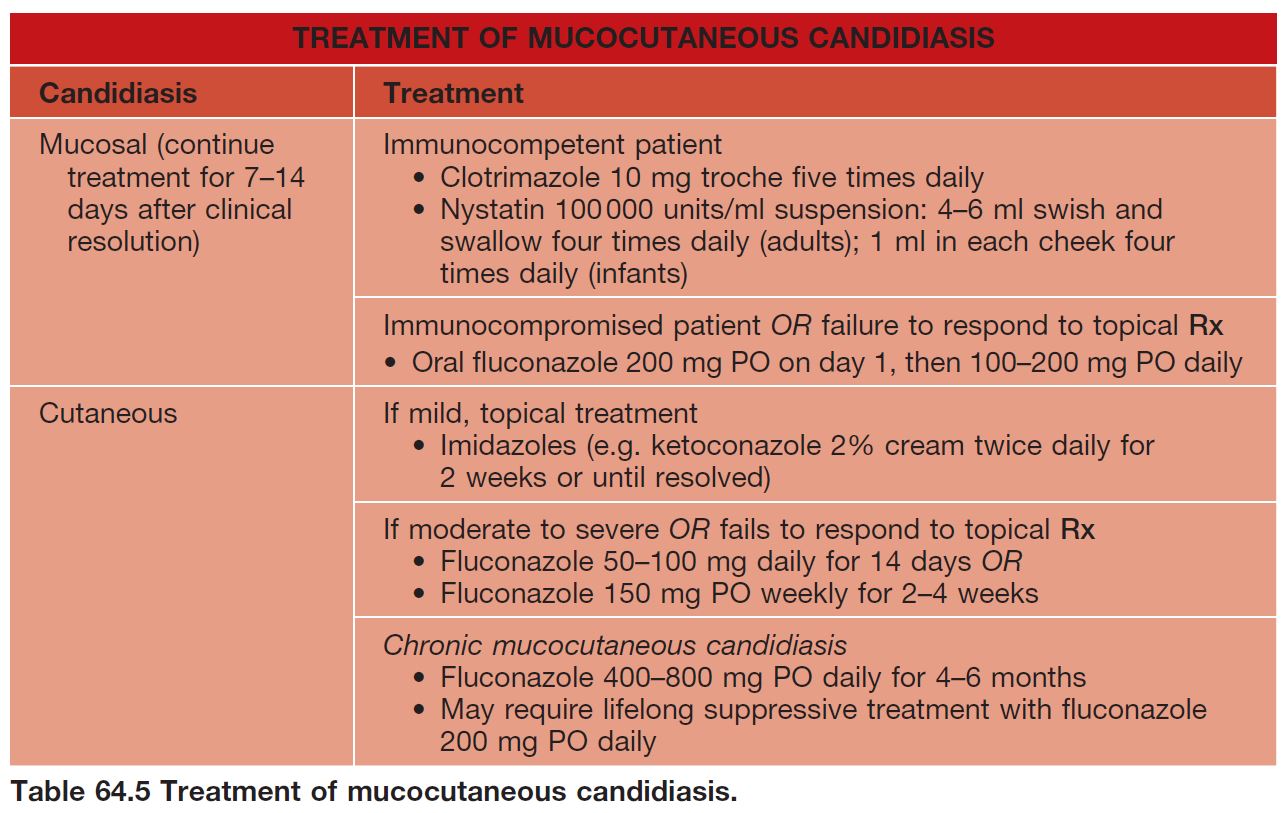

• Mucosal.

– Oral candidiasis (thrush) presents as a white exudate resembling cottage cheese; risk factors include diabetes mellitus, treatment with broadspectrum antibiotics, use of inhaled CS, dentures, and immunosuppression; common in otherwise healthy neonates and infants.

– Additional forms: intraoral erythematous patches and adherent white plaques, glossitis, angular cheilitis (see Fig. 13.5), and vulvovaginitis and balanitis (see Chapter 60).

• Cutaneous.

– Most common presentation is an erosive, erythematous patch with satellite pustules in an intertriginous zone (inframammary, axillary, inguinal, beneath a pannus; Fig. 64.15), on the scrotum, or in the diaper area of infants (see Fig. 13.4).

– Predisposing factors for cutaneous infection – similar to oral candidiasis plus hyperhidrosis with occlusion.

• DDx of candidal intertrigo: see Chapter 13.

• Rx: outlined in Table 64.5.

• Rx of candidal intertrigo or balanitis: outlined in Table 60.5.

Systemic Candidiasis

• Generally affects immunosuppressed hosts in the setting of neutropenia.

• Clinical features are outlined in Table 64.6.

• Although the skin lesions represent septic emboli, blood cultures may be negative; as a result, skin biopsy for tissue culture and histology can play a critical role.

Congenital Candidiasis

Congenital candidiasis is discussed in Chapter 28.

Perianal Pseudoverrucous Papules (Granuloma Gluteale Infantum)

• Etiology is multifactorial, including moist occlusion, irritation from urine and stool, and candidal infection.

• Seen primarily in infants but also in older individuals with urinary and fecal incontinence.

• Erythematous papules and nodules, as well as erosions, develop in the anogenital region.

• DDx: outlined in Fig. 13.4.

Deep Fungal Infections

Deep mycoses are treated with oral or intravenous antifungal medications, often for an extended period of time (e.g. 6 months). Culture results direct therapy, but initial empiric treatment is often started based on the clinical presentation plus histologic findings (e.g. itraconazole 200–400 mg/day for chromoblastomycosis).

Dermal/Subcutaneous

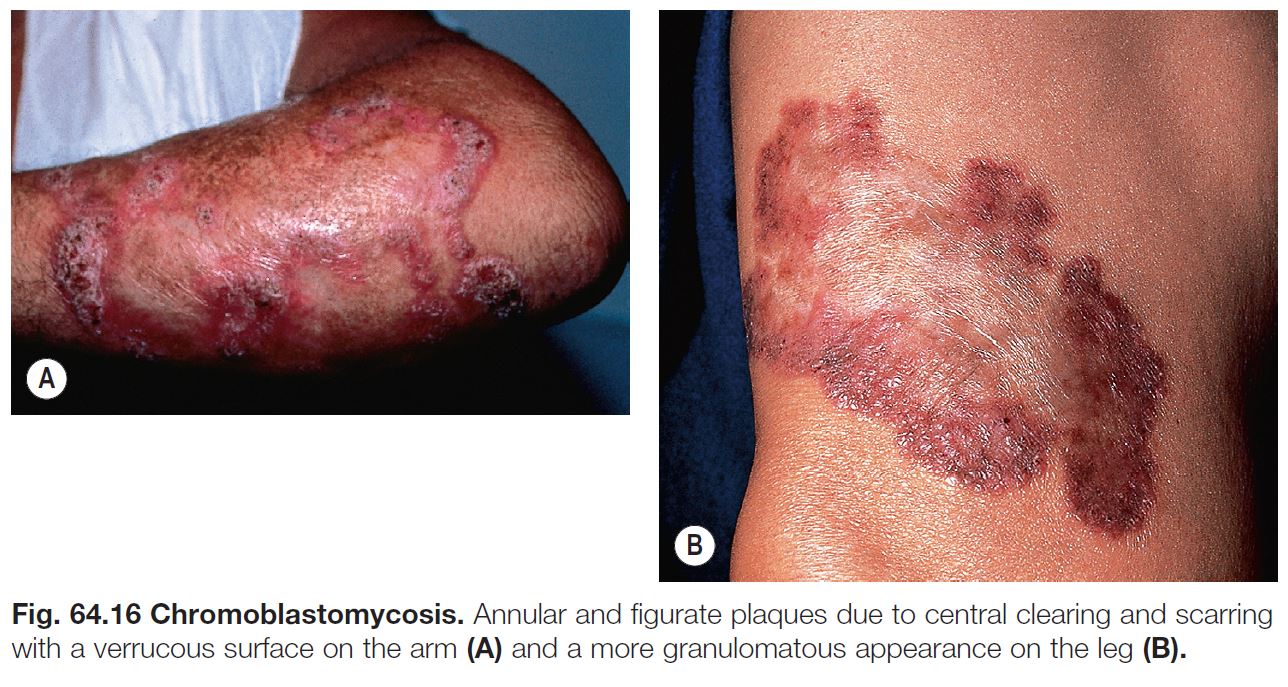

Chromoblastomycosis

• Commonly due to several species of dematiaceous fungi – Fonsecaea pedrosoi, F. compacta, F. monophora, Phialophora verrucosa, Cladosporium carrionii, and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa – that are found in soil and decaying wood.

• Follows trauma and implantation of the

fungus into the skin.

• Expanding, verrucous plaque, usually on an extremity (Fig. 64.16); central scarring can occur.

• More common in tropical and subtropical regions.

• Diagnostic histologic finding – round, pigmented bodies with internal septations that are said to resemble copper pennies, also referred to sclerotic bodies or Medlar bodies.

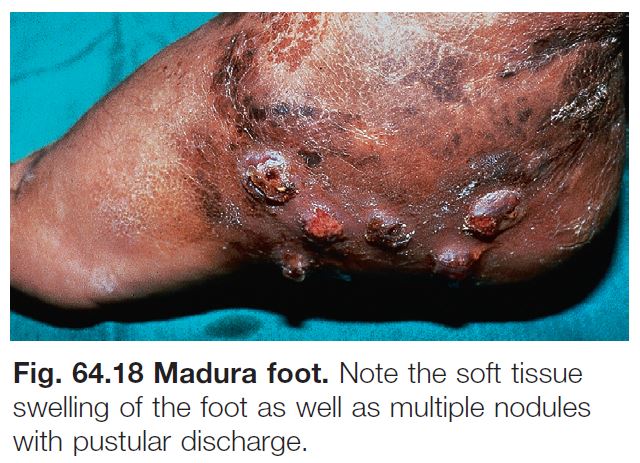

Mycetoma (Madura Foot)

• Two subtypes: (1) actinomycotic mycetoma – secondary to filamentous bacteria, especially Nocardia and Actinomyces (see Chapter 61); and (2) eumycotic mycetoma – caused by true fungi, e.g. Madurella mycetomatis, Pseudallescheria boydii.

• Contracted from trauma and implantation of fungus into the skin (Fig. 64.17A).

• Most common site is the distal lower extremity but can also be seen in other sites, such as the distal upper extremity, trunk, and scalp.

• Clinical triad of draining sinuses, grains (macroscopic colonies of organisms; see Chapter 61), and edema (Fig. 64.18). • Rx: excision of more localized lesions; for larger areas of involvement as well as pre- and postoperatively, long-term course (i.e. 6 months or longer) of oral antifungal medication (e.g. itraconazole 400 mg PO daily × 3 months followed by 200 mg PO daily for 9 months).

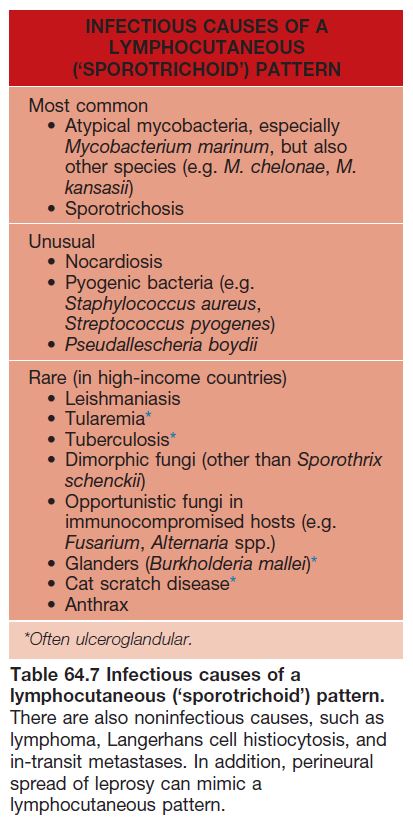

Sporotrichosis

• Secondary to Sporothrix schenkii, a dimorphic fungus, i.e. a yeast at 37°C (human body) and a mold at 25°C (soil).

• Worldwide distribution; present in soil and sphagnum moss.

• Most common presentation is a lymphocutaneous or ‘sporotrichoid’ pattern (~75% of patients) that initially presents as a papule or nodule at the site of inoculation; this is followed by the appearance of papulonodules along the draining lymphatics (Fig. 64.19; Table 64.7).

• Less common variants: (1) a fixed, ulcerated plaque on the face in someone with prior exposure, a form prevalent in Brazil due to transmission by infected cats; and (2) cutaneous dissemination from a systemic infection.

Systemic (Unless Primary Inoculation into Skin)

Blastomycosis

• Due to Blastomyces dermatitidis, a dimorphic fungus; yeast form displays broad-based budding (see Fig. 64.17C).

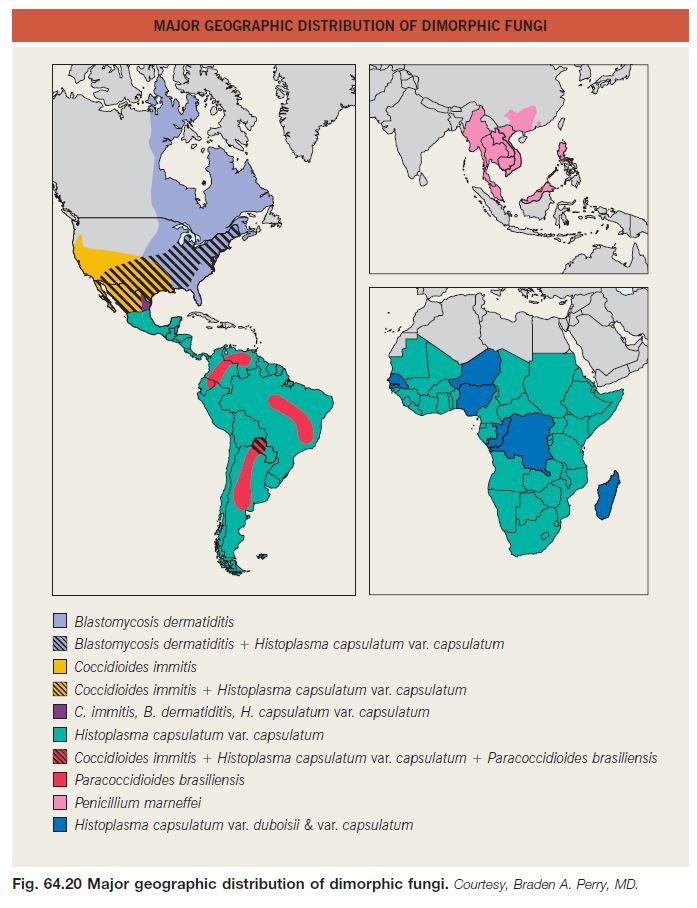

• Endemic to the southeastern United States and other areas of North America (Fig. 64.20).

• Contracted via inhalation, with the skin, bones, and genitourinary tract being the most common sites of secondary infection.

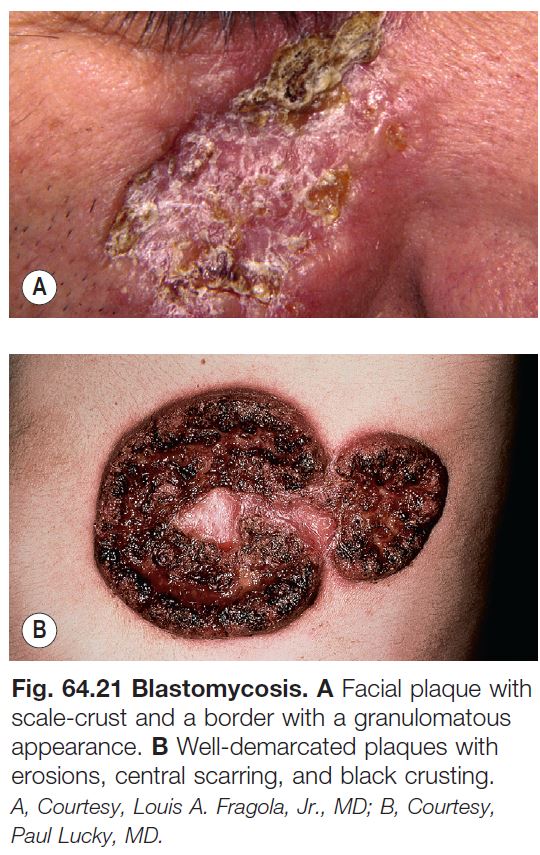

• Cutaneous lesions can vary from papulopustules to verrucous plaques with crusted borders (Fig. 64.21).

Coccidioidomycosis

• Due to Coccidioides immitis, a dimorphic fungus that forms arthrospores in the soil and spherules within the skin (see Fig. 64.17D).

• Endemic to the southwestern United States (see Fig. 64.20).

• Contracted via inhalation, with disseminated disease more common in African-Americans, Mexicans, and immunocompromised hosts.

• Cutaneous manifestations: lesions vary from papules to pustules, abscesses, and plaques with sinus tracts (Fig. 64.22).

• Noninfectious hypersensitivity reactions include toxic erythema, erythema multiforme, and erythema nodosum.

• Molluscum contagiosum-like lesions may be seen in HIV-infected persons.

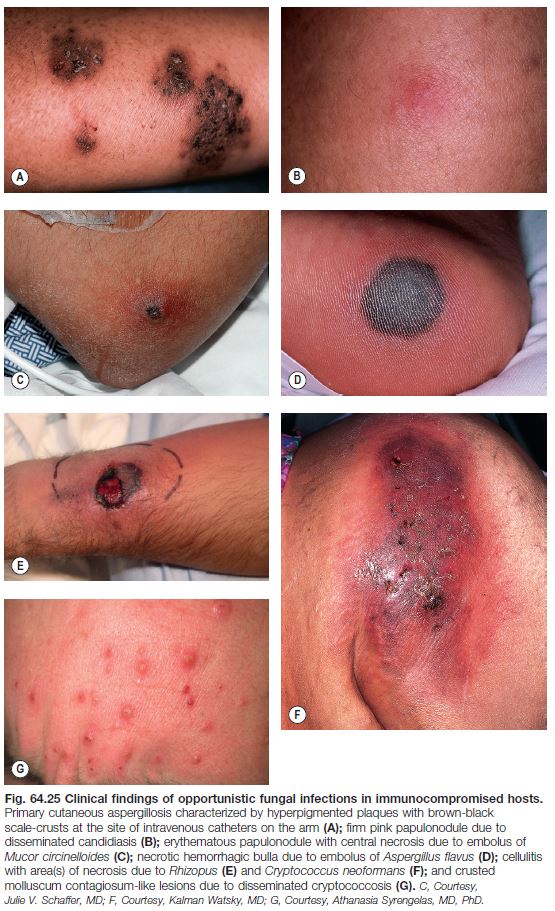

Cryptococcosis

• Molluscum contagiosum-like lesions may be seen in HIV-infected patients and other immunocompromised hosts (see Fig. 64.25G), in addition to ulcers and cellulitis (see Fig. 64.25F).

Histoplasmosis

• Due to Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus (see Fig. 64.17B).

• Endemic to the southeastern and central United States and many other countries with reservoirs in birds, including fowl, and bats (see Fig. 64.20).

• Disease contracted through inhalation or, rarely, implantation.

• Immunocompetent hosts: oral ulcers in up to 75% of patients; occasionally cutaneous papulonodules.

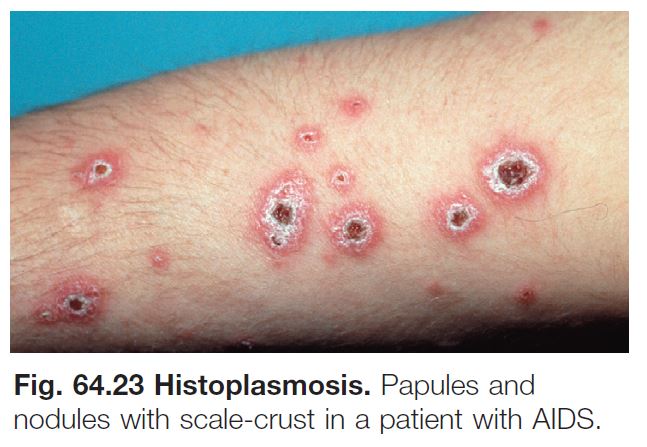

• Immunosuppressed hosts: oral ulcers and multiple papules or plaques (Fig. 64.23), including ones that resemble molluscum contagiosum.

Paracoccidioidomycosis

• Due to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, a dimorphic fungus that displays multiple narrow-based buds in tissue, including the skin.

• Endemic to South America.

• Disease contracted via inhalation, with dissemination primarily to lymph nodes > oropharynx > adrenal glands > spleen and gastrointestinal tract, in addition to the skin.

• Cutaneous lesions are primarily periorificial and associated with involvement of the oral mucosa; verrucous and ulcerative plaques are seen (Fig. 64.24).

Opportunistic Pathogens

See Table 64.6 and Fig. 64.25.