Introduction/Definitions

• Leukoderma and hypopigmentation: areas of skin are lighter in color than uninvolved skin, due primarily to a decrease in melanin; decreased blood supply to the skin (e.g. nevus anemicus) can be another cause of leukoderma.

• Hypomelanosis: an absence or reduction of melanin in the skin that may be due to any one or a combination of the following:

1. A decrease in the number of melanocytes (e.g. vitiligo).

2. A decrease in melanin synthesis by a normal number of melanocytes (e.g. albinism).

3. A decrease in the transfer of melanin to keratinocytes (e.g. postinflammatory hypopigmentation).

• Amelanosis: total absence of melanin in the skin.

• Depigmentation: usually implies a total loss of skin color (e.g. as in vitiligo).

• Pigmentary dilution: a generalized lightening of the skin, hair, and eyes (e.g. oculocutaneous albinism); sites of melanin production include the epidermis, hair follicles, pigmented retinal epithelium, and uveal tract.

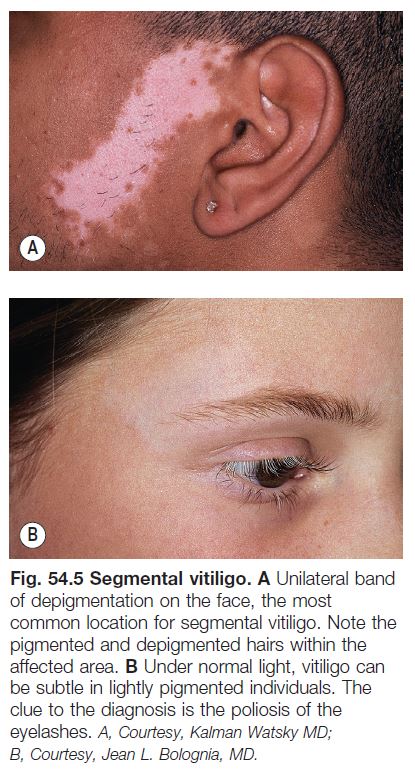

• Poliosis: a lock of scalp hair, eyebrows, or eyelashes that is white or lighter in color.

• Canities: generalized depigmentation of scalp hair.

• Wood’s lamp examination: the greater the loss of epidermal pigmentation, the more marked the contrast with uninvolved skin on Wood’s lamp examination.

• All disorders of hypopigmentation are more easily observed in darkly pigmented individuals or after a suntan.

Approach to Disorders of Hypopigmentation

• Assess the following parameters:

1. Age of onset (e.g. birth/infancy vs. childhood vs. adulthood).

2. Presence or absence of preceding inflammation.

3. Distribution pattern (see below) and anatomic location.

4. Degree of pigment loss.

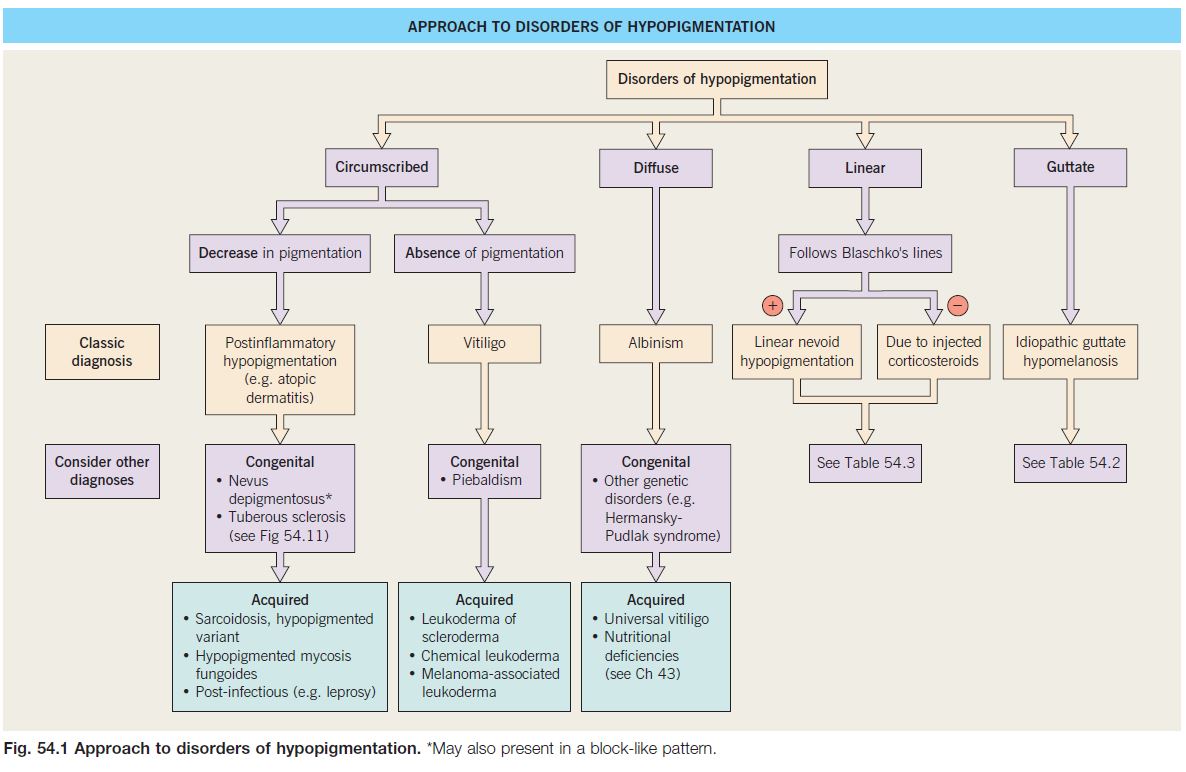

• The distribution patterns can be divided into circumscribed (e.g. vitiligo), diffuse (e.g. albinism), linear, or guttate (e.g. idiopathic guttate hypomelanosis).

• An approach to leukoderma is outlined in Fig. 54.1.

Vitiligo

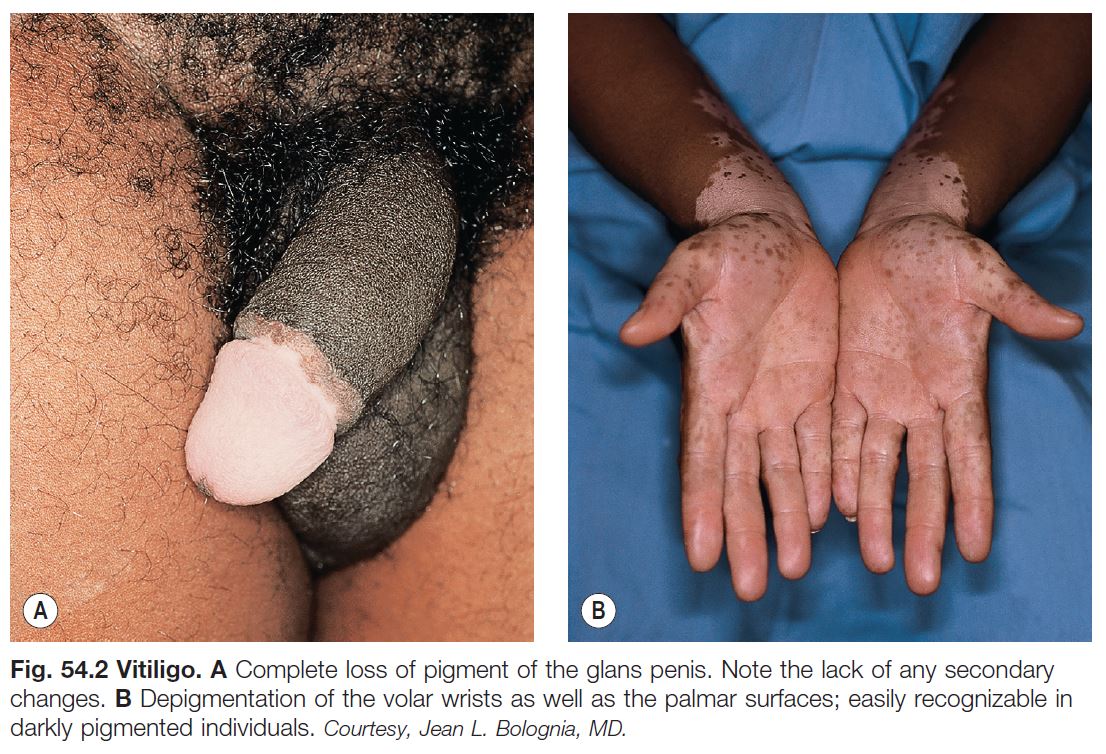

• An acquired disease, due to autoimmune destruction of melanocytes, that is characterized by circumscribed, amelanotic macules or patches of the skin and mucous membranes (Fig. 54.2); hairs within involved areas may be depigmented or pigmented; the uveal tract and retinal pigmented epithelium can also be affected.

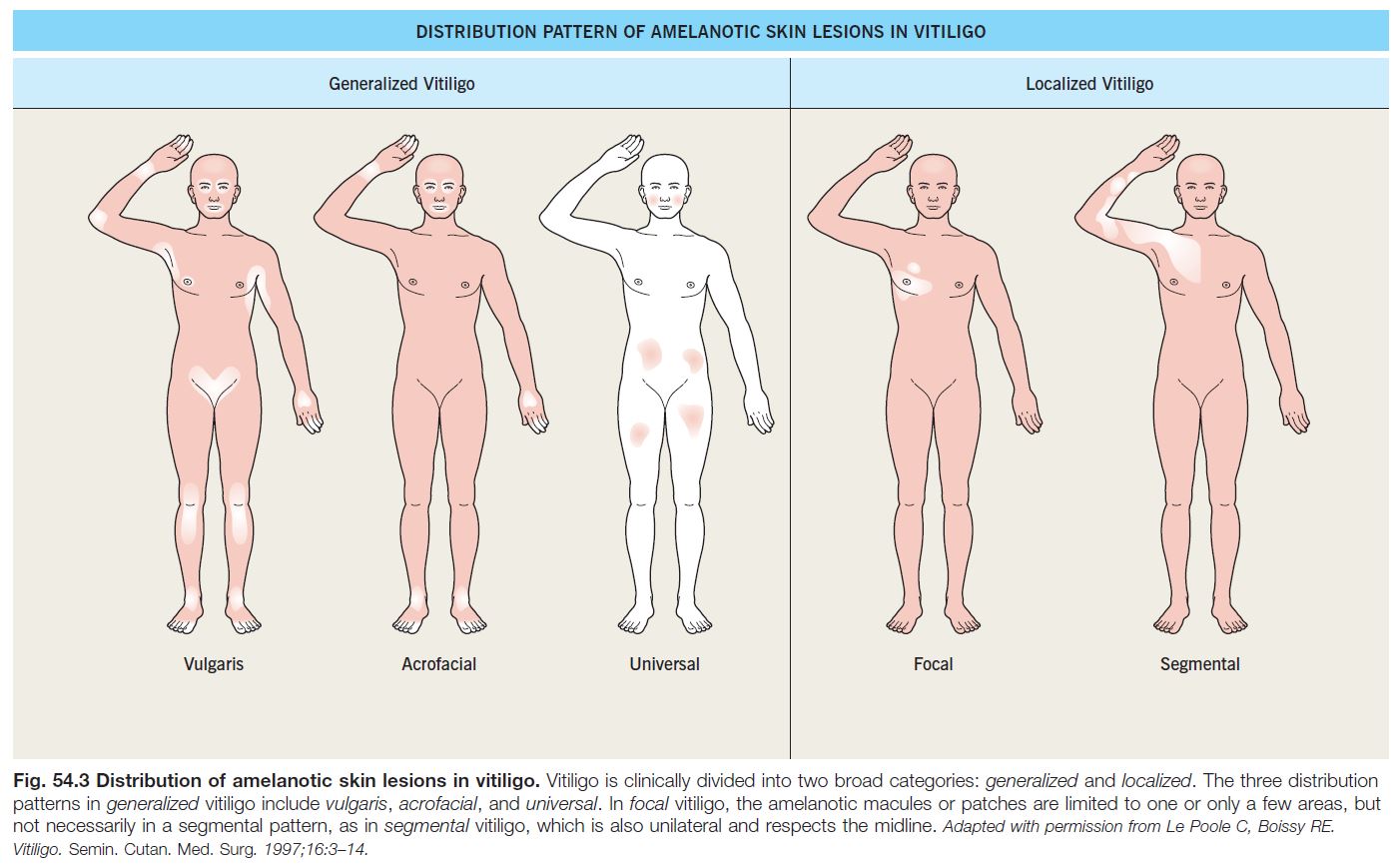

• Two major subtypes of vitiligo: generalized (most common) and localized (Fig. 54.3).

• A polygenic disorder, i.e. involving multiple susceptibility genes, plus environmental factors (mostly unknown); increased incidence of other autoimmune disorders, either in the individual with vitiligo (generalized > localized) or in family members.

• 10–15% of patients with generalized vitiligo have systemic autoimmune diseases, in particular thyroid disease (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or Grave’s disease), pernicious anemia, Addison’s disease, and AI-CTD (e.g. SLE); associated cutaneous disorders include halo melanocytic nevi, alopecia areata, and lichen sclerosus.

• Generalized vitiligo.

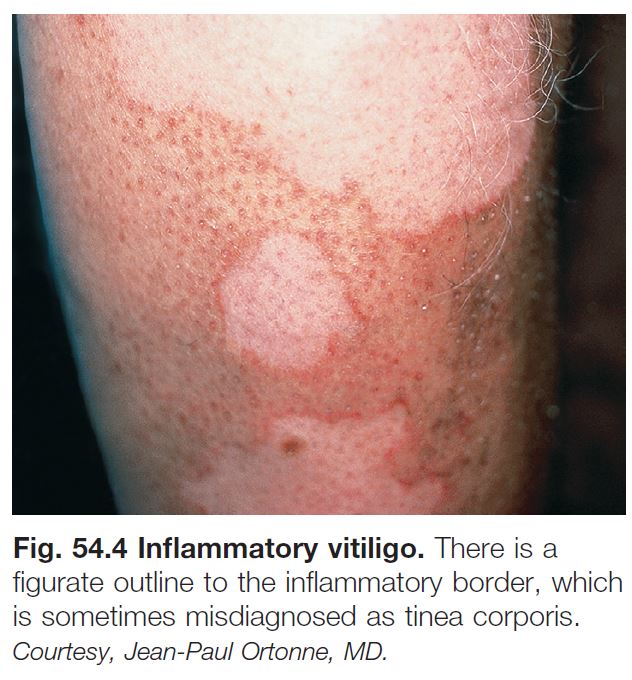

– Includes acrofacial, vulgaris, and universal (see Fig. 54.3); occasionally an inflammatory edge is seen (Fig. 54.4).

– Affects ~1% of the population worldwide; males = females; onset in ~50% before age 20 years; onset after age 50 years is unusual and prompts widening of the DDx (see below).

– The typical lesion is an asymptomatic, amelanotic macule or patch that is milk or chalk-white in color; early on the pigment loss may not be complete; margins are fairly discrete and convex.

– Course is unpredictable, but often progressive.

• Segmental vitiligo.

– Usually begins in childhood; typically presents in a unilateral, segmental pattern that respects the midline and usually remains stable in size after 1–2 years (Fig. 54.5).

– DDx: nevus depigmentosus (decreased but not total loss of pigment).

• DDx of depigmented lesion(s).

– In a child: if 1–2 isolated circular or oval macules, stage 3 halo nevus; piebaldism, Waardenburg syndrome (see below).

– In an adult: chemical leukoderma, melanoma-associated leukoderma, leukoderma of scleroderma, Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome, onchocerciasis, and postinflammatory depigmentation (see below).

– With the exception of onchocerciasis, or in areas of sclerosis or inflammation, a biopsy is not particularly helpful.

• Vitiligo and ocular disease.

– Uveitis is the most significant ocular abnormality; asymptomatic depigmented areas of the ocular fundus can also be seen.

– Uveitis is a major component of the Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada syndrome, in which patients also develop aseptic meningitis, otic involvement (e.g. dysacousia), poliosis, and vitiligo, especially of the head and neck region.

– Alezzandrini syndrome is a rare disorder characterized by unilateral facial vitiligo, poliosis, and ipsilateral ocular involvement.

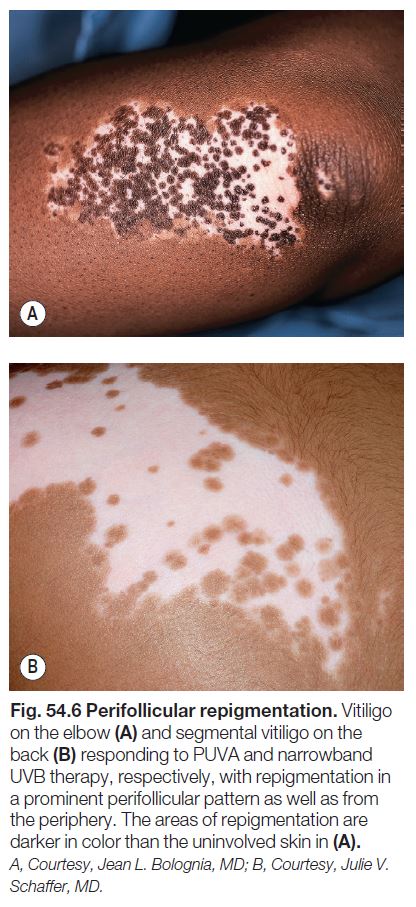

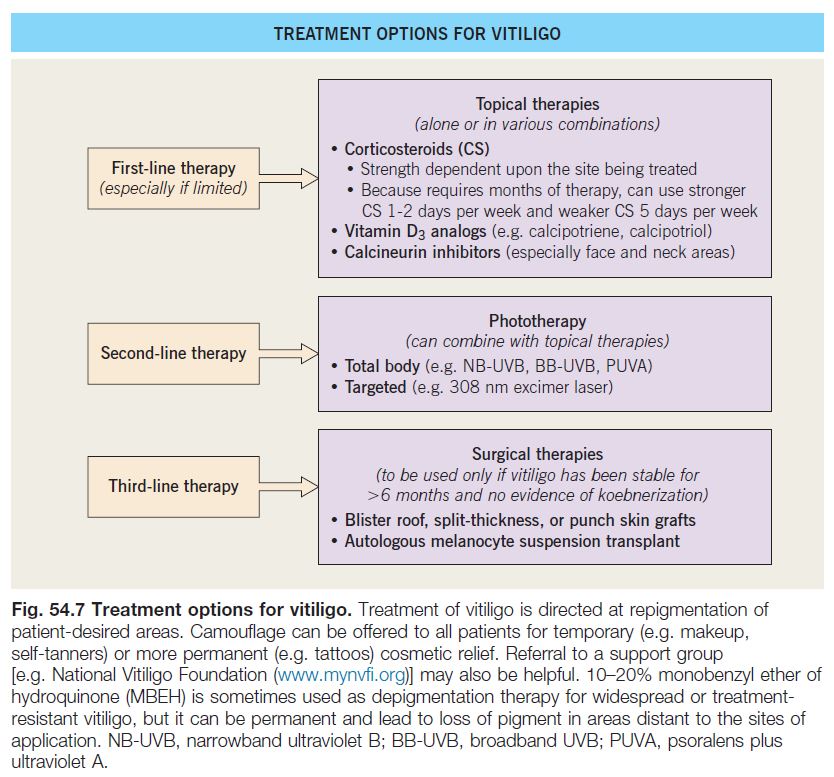

• Rx: primarily directed at repigmentation of patient-desired areas (Fig. 54.7).

– The efficacy of treatment depends on four variables.

1. Site: face, neck, mid extremities > acral, mucosal (i.e. sites without hairs).

2. Extent of involvement: small area > large area.

3. Stability: stable > active or progressive.

4. Pigmented hairs within the vitiligo patch: presence > absence.

– Repigmentation usually appears in a perifollicular pattern (Fig. 54.6) and/or from the periphery of lesions.

– 10–20% monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone (MBEH) is sometimes used as depigmentation therapy for widespread or treatment-resistant vitiligo, but it can be permanent and lead to loss of pigment in areas distant to the sites of application.

Hereditary Hypomelanosis

Oculocutaneous Albinism (OCA)

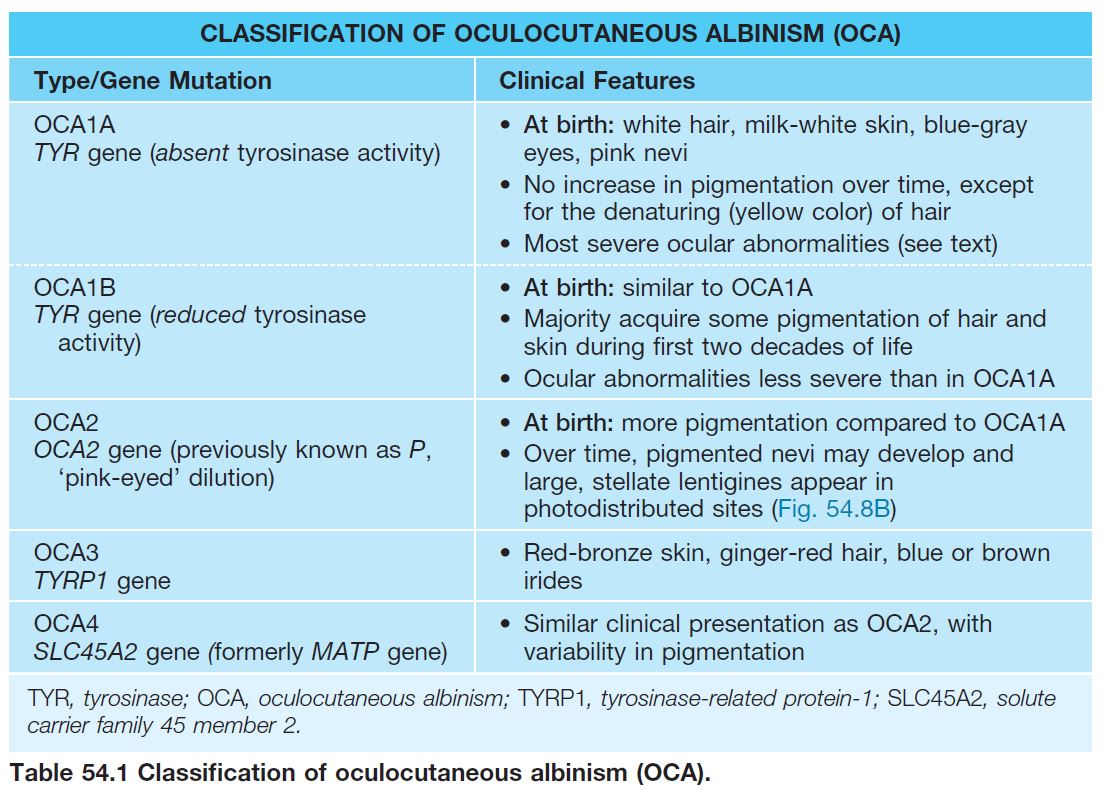

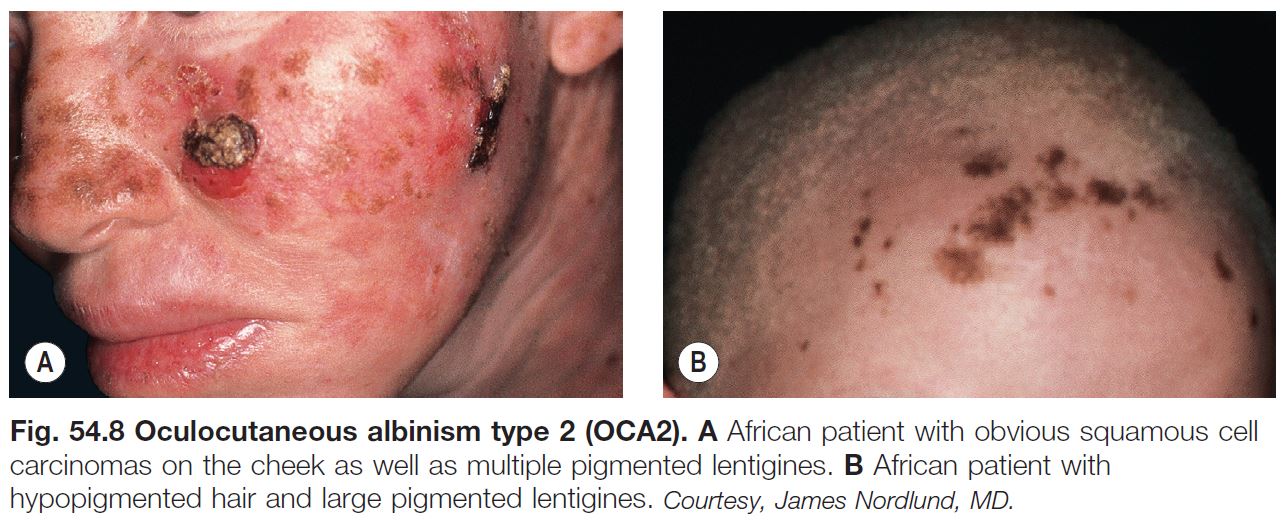

• A group of genetic disorders characterized by pigmentary dilution due to a partial or total absence of melanin within the skin, hair follicles, and eyes; the number of melanocytes is normal.

• Estimated frequency is 1 : 20 000, but may be 1 : 1500 in areas of Africa.

• Four subtypes of OCA (Table 54.1) exist; nearly always inherited in an autosomal recessive manner; OCA1 and OCA2 constitute ~90% of all cases of OCA.

• The ocular manifestations are due to a decrease of melanin within eye structures (e.g. photophobia, reduced visual acuity) or the misrouting of optic nerve fibers during development (e.g. strabismus, nystagmus, lack of stereoscopic vision).

• Early ophthalmologic consultation and strict photoprotection are mandatory; the development of aggressive SCCs (Fig. 54.8A) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality.

Disorders of Melanocyte Development

PIEBALDISM

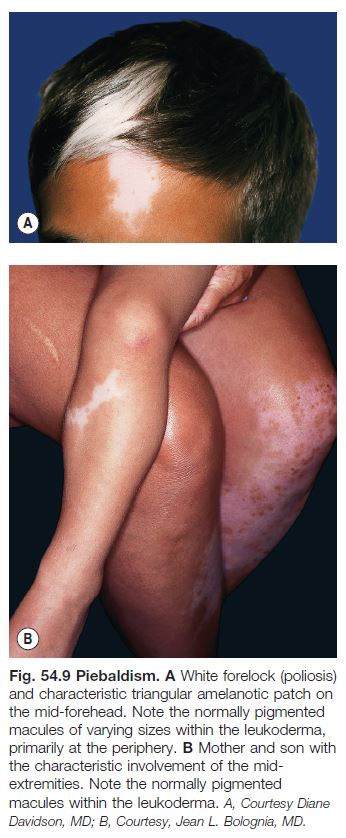

• A rare autosomal dominant congenital disorder resulting from mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene, causing abnormal melanocyte development.

• Presents at birth with poliosis of the mid frontal scalp and stable circumscribed areas of amelanosis in a characteristic distribution pattern, favoring the anterior trunk, mid extremities, and central forehead (Fig. 54.9).

• Areas of amelanosis contain normally pigmented and hyperpigmented macules and patches within them (see Fig. 54.9); the latter can be seen in uninvolved skin.

• Rx: amenable to autologous skin grafting given its stability.

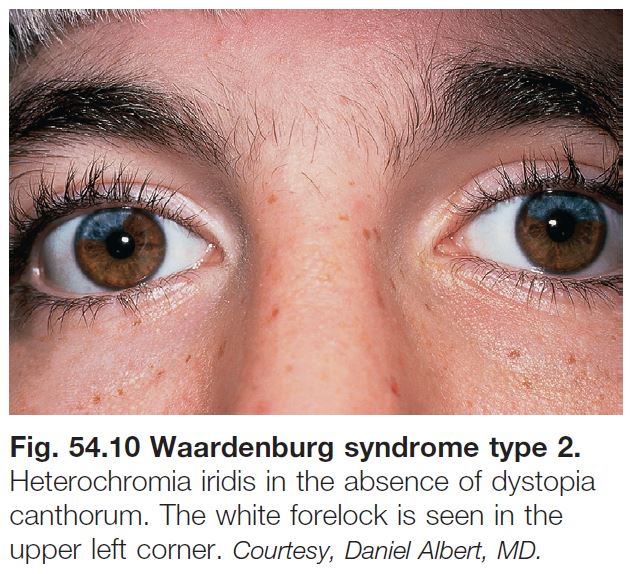

WAARDENBURG SYNDROME (WS)

• A rare autosomal dominant or recessive disorder characterized by.

– Skin lesions resembling piebaldism, including the white forelock.

– Congenital deafness (10–40%).

– Partial or total heterochromia iridis.

– Medial eyebrow hyperplasia (synophrys).

– Broad nasal root.

– Dystopia canthorum (increase in the distance between the inner canthi with normal interpupillary distance).

• Four clinical subtypes have been described.

– WS1: classic form.

– WS2: lacks dystopia canthorum (Fig. 54.10).

– WS3: associated limb abnormalities.

– WS4: associated with Hirschsprung disease.

Disorders of Melanosome Biogenesis

• Because biosynthesis of lysosome-related organelles, e.g. platelet-dense granules and lytic granules of cytotoxic lymphocytes and natural killer cells, are also affected, patients can have a bleeding diathesis and immunodeficiency.

HERMANSKY–PUDLAK SYNDROME (HPS)

• Autosomal recessive inheritance; eight subtypes; HPS1 and HPS3 are the most common subtypes seen in Puerto Ricans.

• Characterized by variable pigmentary dilution of skin, hair, and eyes, depending on ethnicity; ocular manifestations of OCA; bleeding tendency; normal platelet count with a prolonged bleeding time.

• Depending on HPS subtype, may develop fatal pulmonary fibrosis and/or granulomatous colitis; average life span is 30–50 years.

• No specific treatment other than platelet transfusions prior to surgery.

CHEDIAK–HIGASHI SYNDROME (CHS)

• Characterized by silvery hair, OCA skin and ocular findings, bleeding diathesis, progressive neurologic dysfunction, and infections due to severe immunodeficiency.

• Giant lysosomes within neutrophils seen on peripheral blood smear.

• Death is often in childhood secondary to infection, bleeding, or an accelerated lymphoma-like phase.

• Rx: hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

Disorders of Melanosome Transport and/or Transfer to Keratinocytes

• Consequences of this disrupted transport are pigmentary dilution and silvery hair (which contains melanin clumps in the hair shafts).

GRISCELLI SYNDROME (GS)

• Autosomal recessive; three subtypes, based on sites of expression of three mutated genes; all characterized by silvery hair and pigmentary dilution; patients can also have neurologic impairment (GS1) or immune abnormalities and hemophagocytic syndrome (GS2).

Other

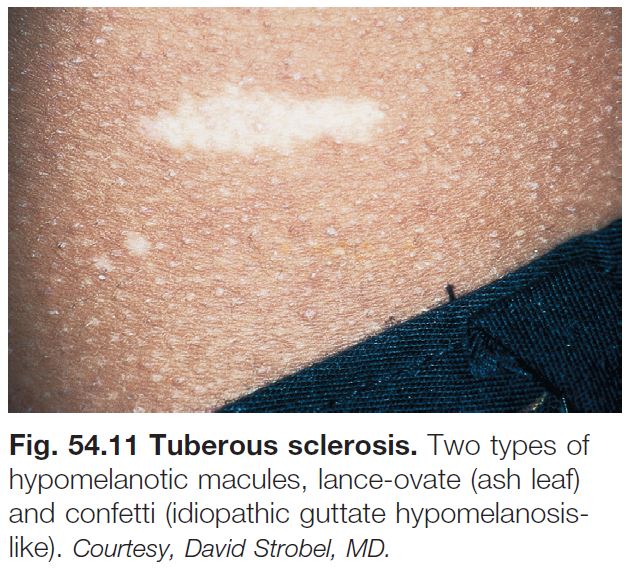

TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS (TS) (See Chapter 50)

• Hypomelanotic macules are often the first sign of TS.

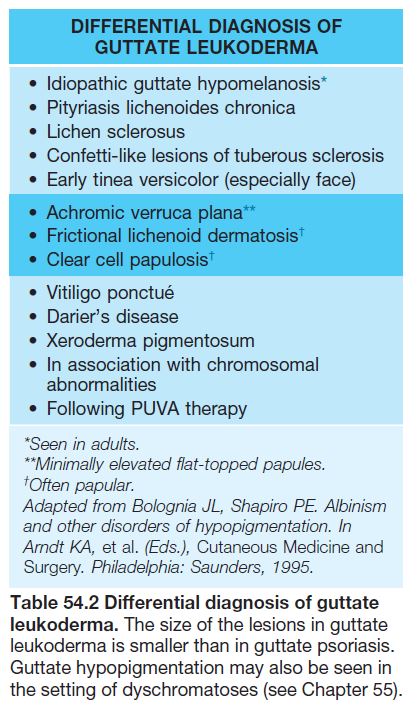

• These hypomelanotic macules are typically multiple in number; polygonal is the most common shape, followed by lance-ovate or ‘ash leaf ’ (Fig. 54.11); less often, the macules are ‘thumbprint’-like, guttate/confetti, or segmental (see Fig. 54.11; Table 54.2); lesions favor the trunk or extremities.

Hypopigmentation in Mosaic Patterns

• Several patterns of hypopigmentation can result from a mosaic ‘clone’ of skin cells with decreased potential for pigment production (‘pigmentary mosaicism’).

• Hypopigmented areas may be apparent at birth or become evident during childhood, especially in patients with fair skin.

LINEAR NEVOID HYPOPIGMENTATION

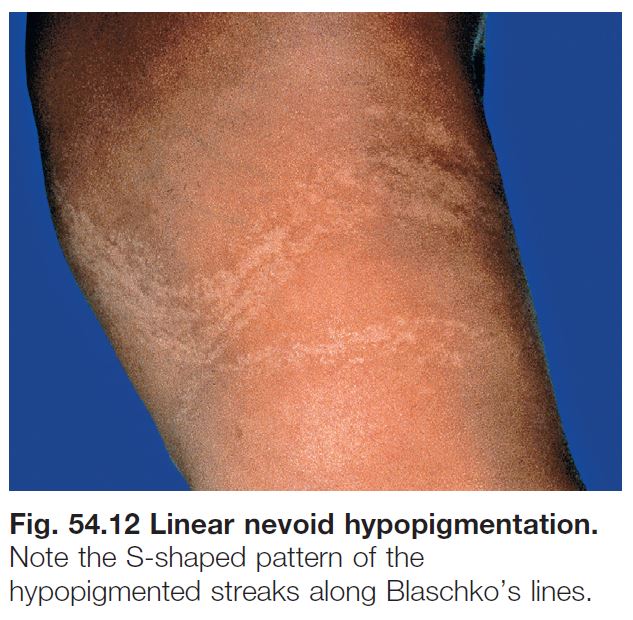

• Localized or widespread streaks and swirls of hypopigmentation that follow Blaschko’s lines, which represent pathways of epidermal cell migration during embryogenesis (Fig. 54.12; see Fig. 51.1).

• ~10–30% of affected individuals have associated extracutaneous abnormalities, which usually develop during infancy and most often affect the CNS (e.g. seizures, developmental delay), eyes, or musculoskeletal system; evaluation is directed by clinical findings.

• The term hypomelanosis of Ito has been used in studies focusing on linear nevoid hypopigmentation associated with systemic manifestations, and it should be reserved for this subset of patients.

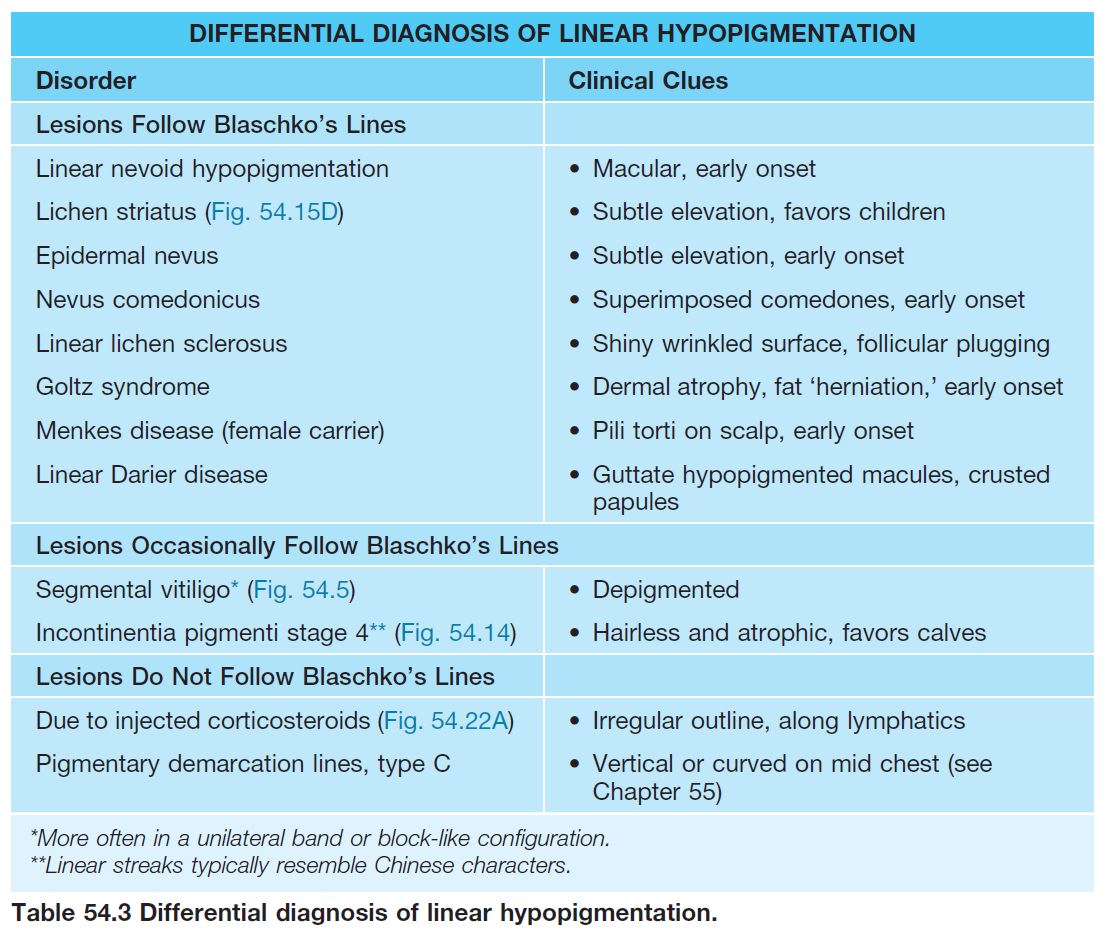

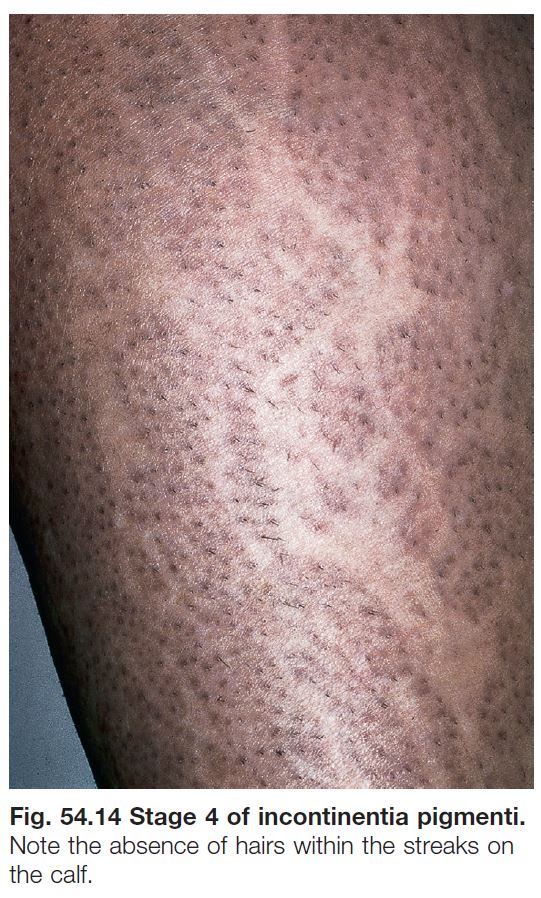

• DDx: outlined in Table 54.3 (see Fig. 54.14).

NEVUS DEPIGMENTOSUS

• Present in ~1 : 50 children, generally as an isolated finding.

• Lesions are typically hypopigmented, not depigmented as implied by the name.

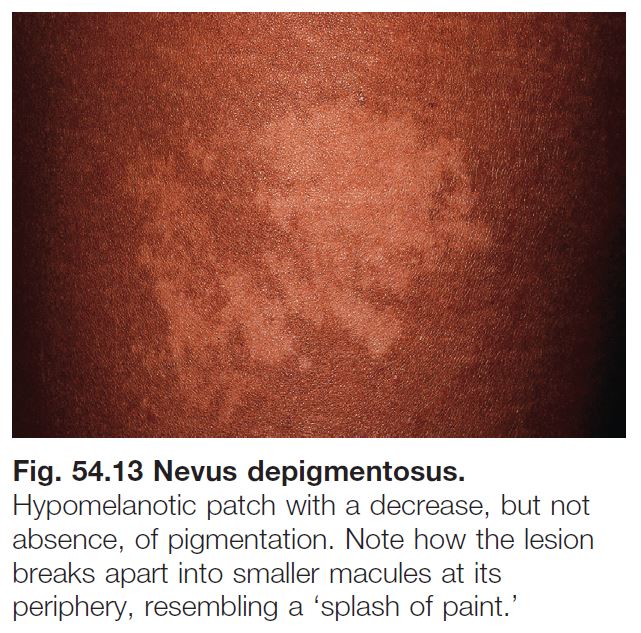

• Classic form: ovoid or irregular hypopigmented patch, often breaking up into smaller macules at its periphery (Fig. 54.13).

• Segmental form (hypopigmented variant of ‘segmental pigmentation disorder’): block-like hypopigmented patch with midline demarcation and less distinct lateral borders.

PHYLLOID HYPOMELANOSIS

• Leaf-shaped and oblong hypopigmented macules and patches in an arrangement resembling a floral ornament, usually in the setting of mosaic trisomy 13 and associated with CNS abnormalities.

Postinflammatory Hypomelanoses

• Inflammatory skin conditions can potentially result in postinflammatory hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation or both (see Chapter 55).

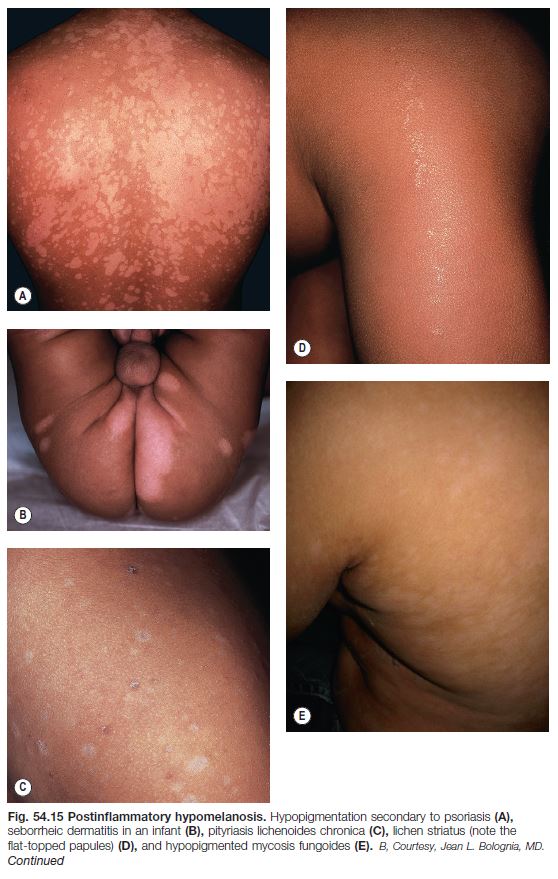

• Postinflammatory hypopigmentation is a very common skin disorder that follows a wide variety of dermatoses, most commonly atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and psoriasis, as well as pityriasis lichenoides chronica, lichen striatus, and lichen sclerosus (Fig. 54.15).

• It typically coexists or co-localizes with the inflammatory lesions, but occasionally only hypopigmented lesions are seen; the size, shape, and distribution pattern often provide clues to the underlying inflammatory dermatosis.

• Most commonly there is a decrease in pigmentation; rarely there is an absence (e.g. severe atopic dermatitis).

• Histopathologic examination is often nonspecific, but in certain diseases (e.g. sarcoidosis and hypopigmented mycosis fungoides) can be diagnostic.

• Rx of underlying dermatosis is followed by gradual resolution.

Pityriasis Alba (See Chapter 10)

• A very common, asymptomatic disorder seen primarily during childhood and adolescence.

• On the malar region of the face, one to several slightly scaly, hypopigmented macules and patches are seen; the lesions are usually ill-defined and occasionally there is associated mild inflammation.

• The hypomelanosis often remains stationary and unchanged for several years; emollients, sunscreens, or low-strength topical CS (e.g. hydrocortisone 2.5%) may be helpful.

• DDx: tinea versicolor, early vitiligo, and postinflammatory hypopigmentation from seborrheic dermatitis or atopic dermatitis.

Sarcoidosis

• Sarcoidosis occurs more commonly in African-Americans, and the hypopigmented variant of cutaneous sarcoidosis may go undiagnosed; this form has no associated prognostic significance and may spontaneously repigment.

• Hypopigmented papules, plaques, or sometimes nodules are seen; range in size from 1 to several cm.

• Histopathology reveals noncaseating granulomas.

Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides (MF) (See Chapter 98)

• A variant of early stage MF that is most commonly observed in darkly pigmented individuals (see Fig. 54.15E); seen in adults, as well as children and adolescents.

• Atrophy often observed within the hypopigmented patches.

• Histopathology reveals typical features of MF.

• DDx: hypopigmented parapsoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC).

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (LE) (See Chapter 33)

• In discoid LE (DLE), hypomelanosis is often seen centrally within well-developed lesions and the lesions also have cutaneous

atrophy, scarring, and a hyperpigmented rim; pigmentary changes tend to be persistent (see Fig. 54.15G).

• In subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE), hypomelanosis typically occurs within the center of annular lesions and is usually reversible.

Systemic Sclerosis (SSc or Generalized Scleroderma) (See Chapter 35)

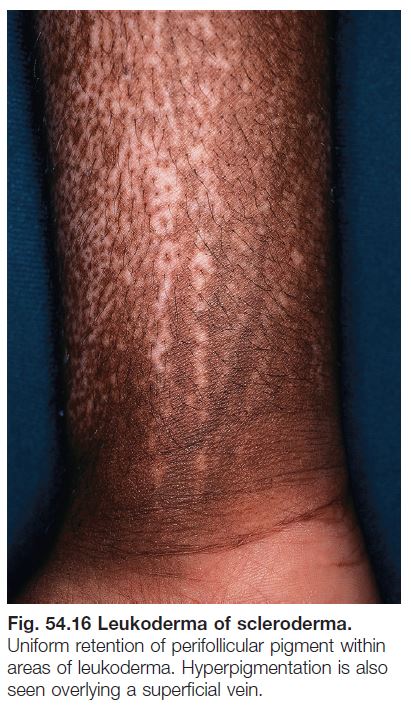

• Patients with SSc can develop several pigmentary abnormalities, including diffuse hypermelanosis with photoaccentuation, mixed hyper- and hypopigmentation in areas of chronic sclerosis, and a characteristic leukoderma in both sclerotic and nonsclerotic skin (Fig. 54.16).

• This ‘leukoderma of scleroderma’ presents as circumscribed areas of depigmentation but with perifollicular and supravenous retention of pigment (see Fig. 54.16).

• This peculiar leukoderma is rather specific for SSc as it occasionally occurs in two other clinical settings, an overlap syndrome (that includes SSc) and scleromyxedema.

• Although clinically similar to the perifollicular repigmentation seen in treatment responsive vitiligo, it is different in that in vitiligo the perifollicular macules represent new pigmentation, whereas in SSc the macules represent old or retained pigmentation.

Lichen Sclerosus (LS) (See Chapter 36)

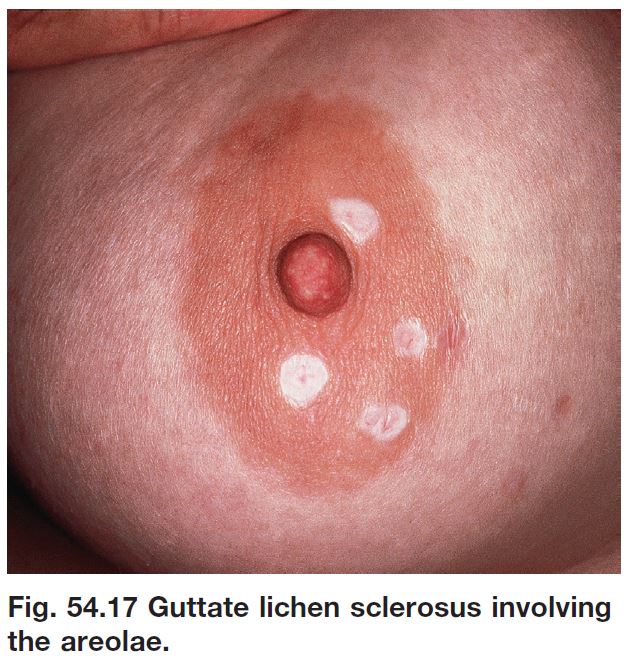

• Genital and extragenital lesions of LS are often hypopigmented, but in addition display cutaneous atrophy, follicular plugging (extragenital), and purpura (genital).

• Occasionally extragenital LS presents as guttate leukoderma (Fig. 54.17; see Table 54.2).

Infectious and Parasitic Hypomelanosis

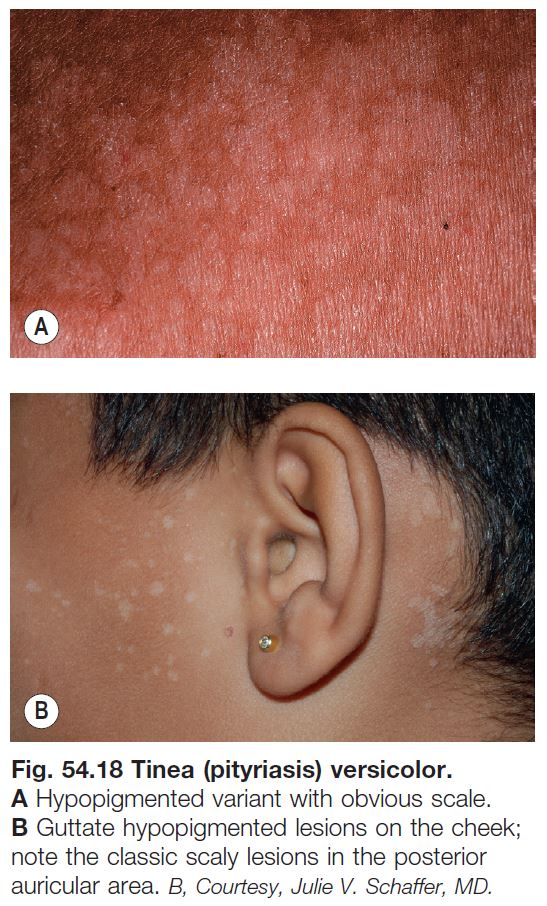

Tinea (Pityriasis) Versicolor (See Chapter 64)

• A very common superficial cutaneous mycosis caused by Malassezia spp.; although there is usually minimal inflammation, this infection can lead to both hyper- and hypopigmentation.

• Typically presents symmetrically on the upper trunk and shoulders or flexural areas (e.g. groin and inframammary) as round to oval macules or thin papules that coalesce into patches or thin plaques; the lesions vary in color from pink to light tan to brown, hence the term versicolor (Fig. 54.18).

• Lesions often coalesce and when untreated, there is usually a subtle overlying fine scale that is more readily apparent upon scratching or stretching the skin.

• Diagnosis is easily confirmed by KOH examination of the associated scale.

• Hypomelanosis without any scaling may remain for months after treatment.

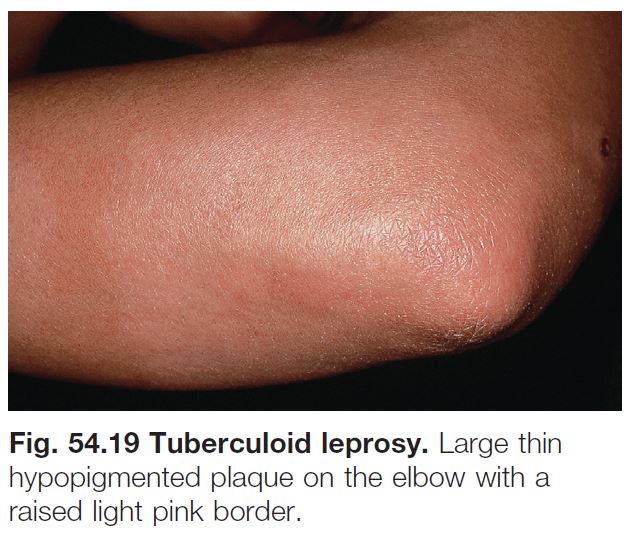

Leprosy (See Chapter 62)

• Tuberculoid leprosy (Fig. 54.19): fewer larger hypopigmented patches with discrete, often raised, borders; favor posterolateral aspects of extremities, back, buttocks, face; associated anhidrosis, alopecia, and loss of sensation.

• Borderline leprosy: occasionally, ill-defined hypomelanotic macules are seen.

• Indeterminate leprosy: erythematous to hypomelanotic macules asymmetrically distributed on exposed sites; normal hair.

• Lepromatous leprosy: hypomelanotic macules may be the earliest manifestation; often small, multiple, subtle, and ill-defined; favor the face, extremities, and buttocks; minimal or no anhidrosis or loss of sensation.

Treponematoses (See Chapters 61 and 69)

• Non-venereal treponematoses (e.g. pinta, yaws, bejel) and venereal syphilis may be associated with hypomelanosis, especially during their untreated phase.

Onchocerciasis (River Blindness) (See Chapter 70)

• A filarial infestation that predominantly affects cutaneous and ocular tissues and is caused by the transmission of Onchocerca volvulus from the bite of a black fly in tropical areas of Africa > Central and South America.

• A later cutaneous finding is leukoderma of the shins with follicular pigmentation, resembling leopard skin (Fig. 54.20).

• DDx: atopic dermatitis with postinflammatory depigmentation, or atopic dermatitis plus vitiligo with Koebner phenomenon.

Other

• Hypopigmentation may also result from cutaneous bacterial or viral infections, e.g. herpes zoster.

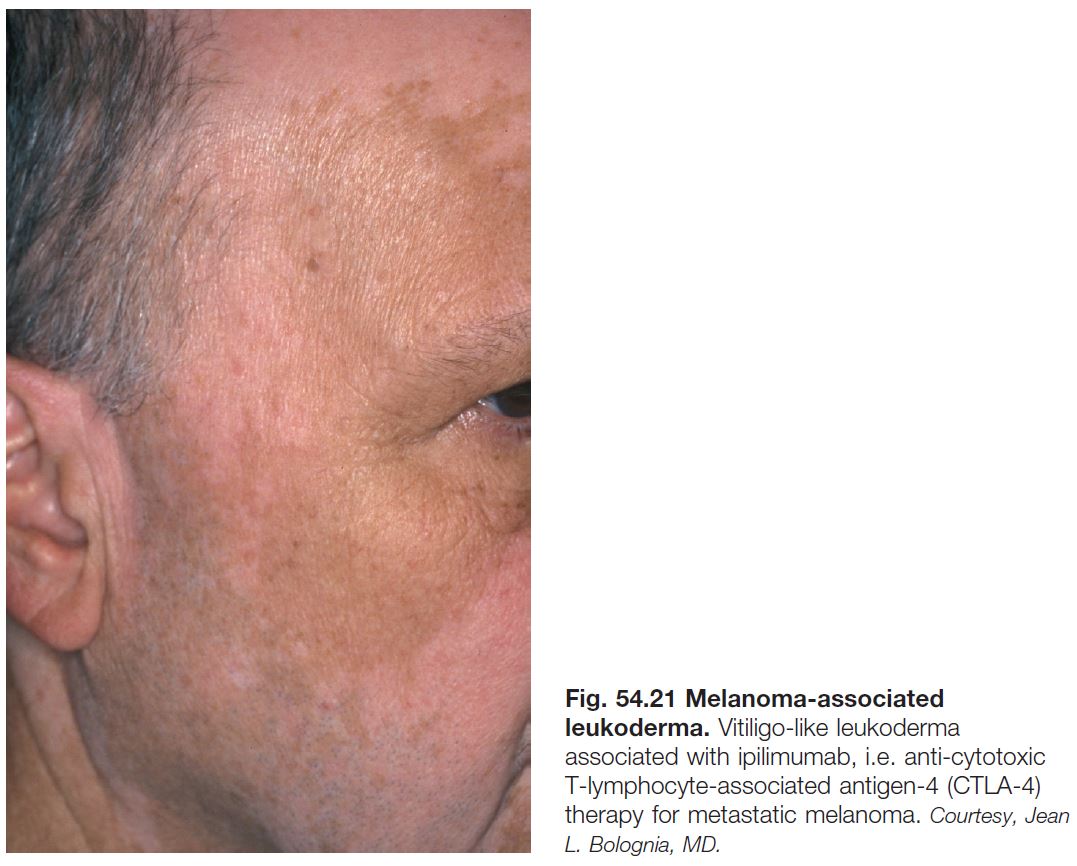

Melanoma-Associated Leukoderma (See Chapter 93)

• Vitiligo-like depigmentation can occur in patients with cutaneous or ocular melanoma, either spontaneously or in the setting of immunotherapy (e.g. interleukin-2, interferon, ipilimumab, lambrolizumab, nivolumab).

• Thought to result from an immune reaction directed against shared antigens on normal and malignant melanocytes (Fig. 54.21).

• Whereas the spontaneous form points to the need for re-staging, the treatment associated form can portend a better prognosis.

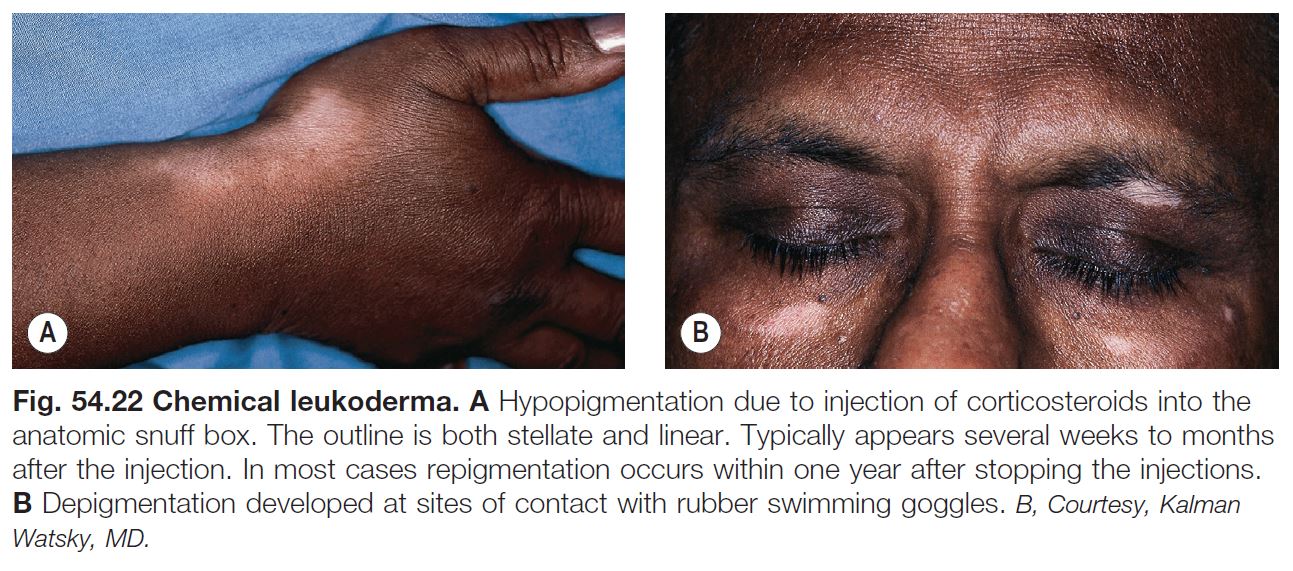

Chemical Leukoderma

• Contact with a number of chemical agents can lead to hypomelanosis of the skin and hair (Fig. 54.22).

• Depigmenting compounds have chemical structures that are similar to melanin precursors; they include catechols, phenols, or quinones (e.g. hydroquinone [HQ] or monobenzyl ether of HQ [MBEH]).

• HQ induces a reversible hypopigmentation, whereas MBEH depigmentation is often permanent and occurs not only at the site of application but also at distant sites.

• Topical and injected CS can also lead to hypopigmentation (see Fig. 54.22).

Miscellaneous

Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis (IGH)

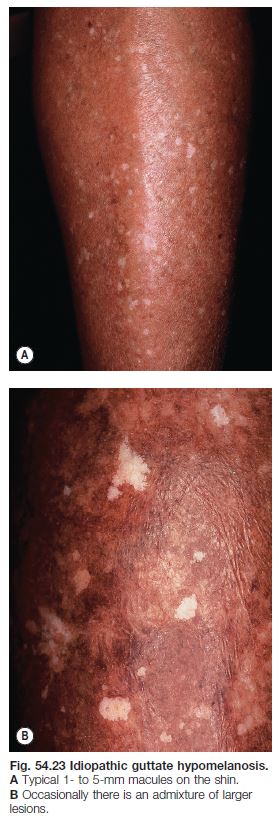

• A very common disorder that increases in incidence with age; occurs in all races and skin types (Fig. 54.23).

• Typically presents as multiple, asymptomatic, small (guttate), well-circumscribed white macules on the extensor forearms and shins; the surface is smooth, often with accentuation of the skin markings.

• DDx: other guttate leukodermas (see Table 54.2).

Progressive Macular Hypomelanosis of the Trunk (PMH)

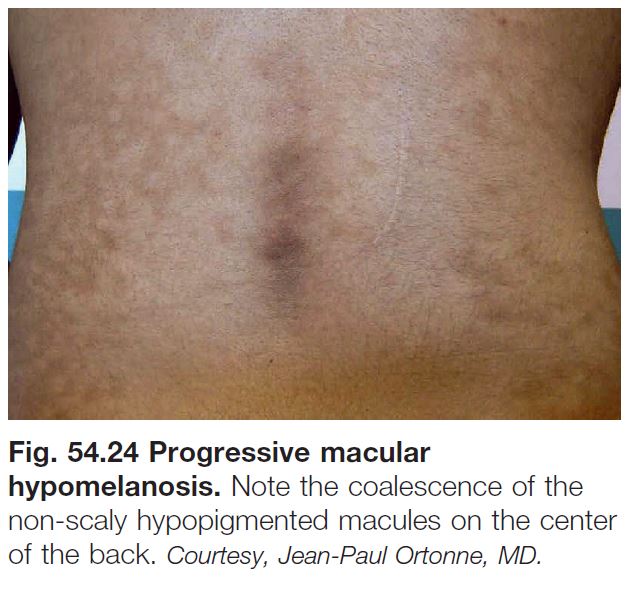

• Characterized by asymptomatic, poorly defined, small, round to oval, non-scaly, hypopigmented macules and patches, primarily on the trunk and proximal upper extremities, often with confluence of lesions (Fig. 54.24).

• A less common variant is seen in Afro-Caribbean females as larger patches.

• DDx: previously treated tinea versicolor.

Hair Hypomelanosis

• Circumscribed (poliosis) versus generalized (canities).

• Graying of hair, either localized or generalized, is characterized by an admixture of normally pigmented, hypomelanotic and amelanotic hairs.

• Whitening of hair is the endpoint of graying of hair, and both are due to defective maintenance of melanocyte stem cells.

• Premature graying of the hair has been associated with a number of genetic disorders (e.g. Werner syndrome, piebaldism) as well as vitiligo.

• Diffuse hypomelanosis of hair has been associated with both hereditary (e.g. Fanconi syndrome) and acquired causes (e.g. tyrosine kinase inhibitors, antimalarials).