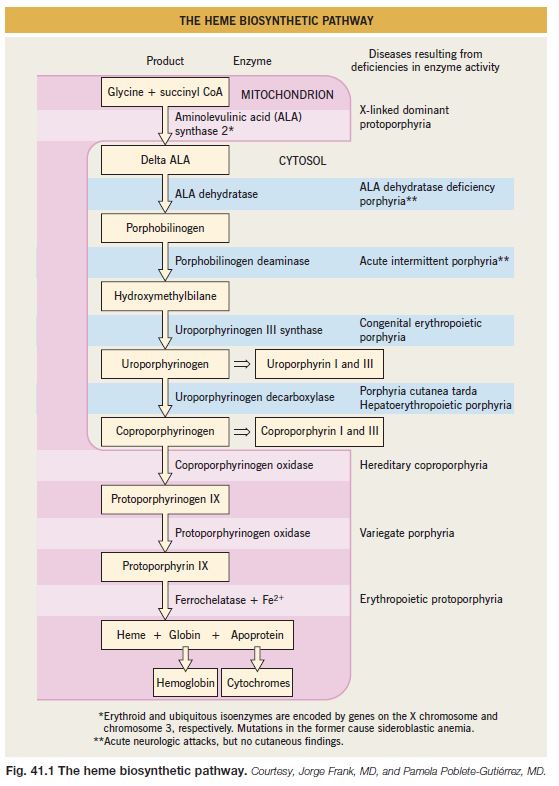

The porphyrias represent a group of metabolic disorders in which there is dysfunction of the enzymes involved in heme synthesis (Fig. 41.1). With the exception of acquired porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT), the underlying etiology is monogenetic mutations. Porphyrins absorb light energy (400–410 nm) and their accumulation within the skin can lead to photosensitization, with water-soluble porphyrins producing blisters and lipophilic porphyrins leading to acute burning and erythema. This chapter focuses on those porphyrias with cutaneous manifestations.

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda (PCT)

• The most common form of cutaneous porphyria; clinical findings typically appear during the 3rd to 4th decade of life.

• Dysfunction of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UD) is usually acquired (type I) but can be inherited in an autosomal dominant manner (type II); the ratio of type I : type II is ~3 : 1.

• In type I PCT, the enzyme is only dysfunctional in the liver, rather than in all tissues; hepatotoxins (e.g. alcohol, iron overload), hepatitis C virus, HIV infection, or estrogens can precipitate or exacerbate PCT.

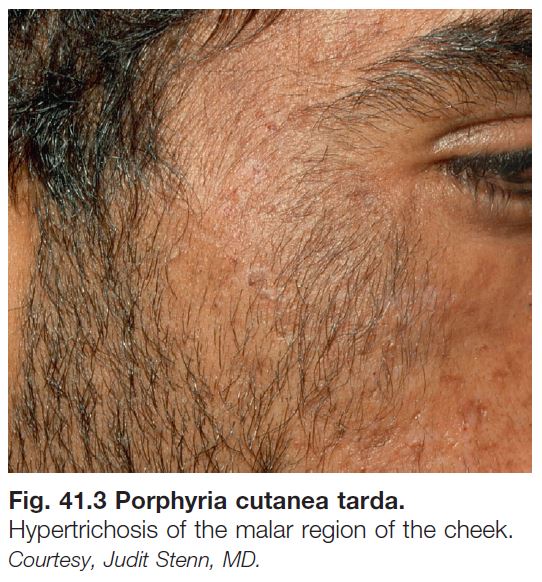

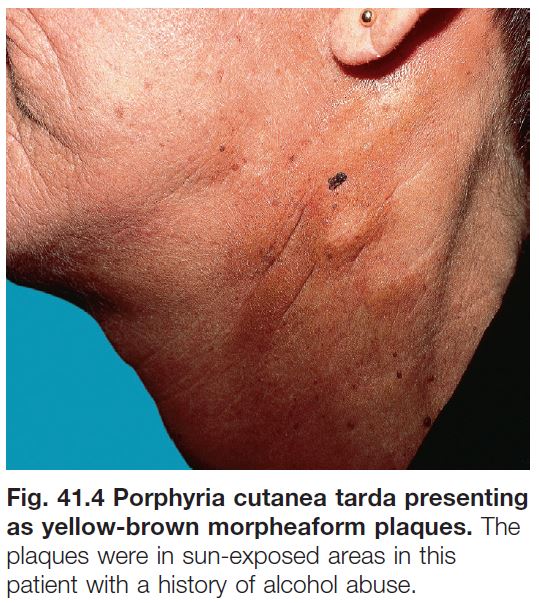

• In addition to photosensitivity, characteristic skin findings include fragility, erosions, vesicobullae, milia, and scars in sun-exposed areas, especially on the dorsal aspects of the hand (Fig. 41.2); hypertrichosis (malar region) and hyperpigmentation can develop on the face (Fig. 41.3); morpheaform plaques are seen less often (Fig. 41.4).

• Histologically, if a bulla is biopsied, there is a subepidermal split with minimal inflammation; thickened basement membranes around capillaries in the dermis with festooning of the dermal papillae are also seen.

• Diagnosis is based on the detection of elevated levels of urinary uro- and coproporphyrins (water-soluble) or elevated plasma uroporphyrins or fecal isocoproporphyrins; genetic analysis can be performed for type II PCT.

• Additional evaluation includes serum ferritin and if elevated, analysis of the hemochromatosis gene, screening for hepatitis B or C viral infection, and if risk factors, HIV infection.

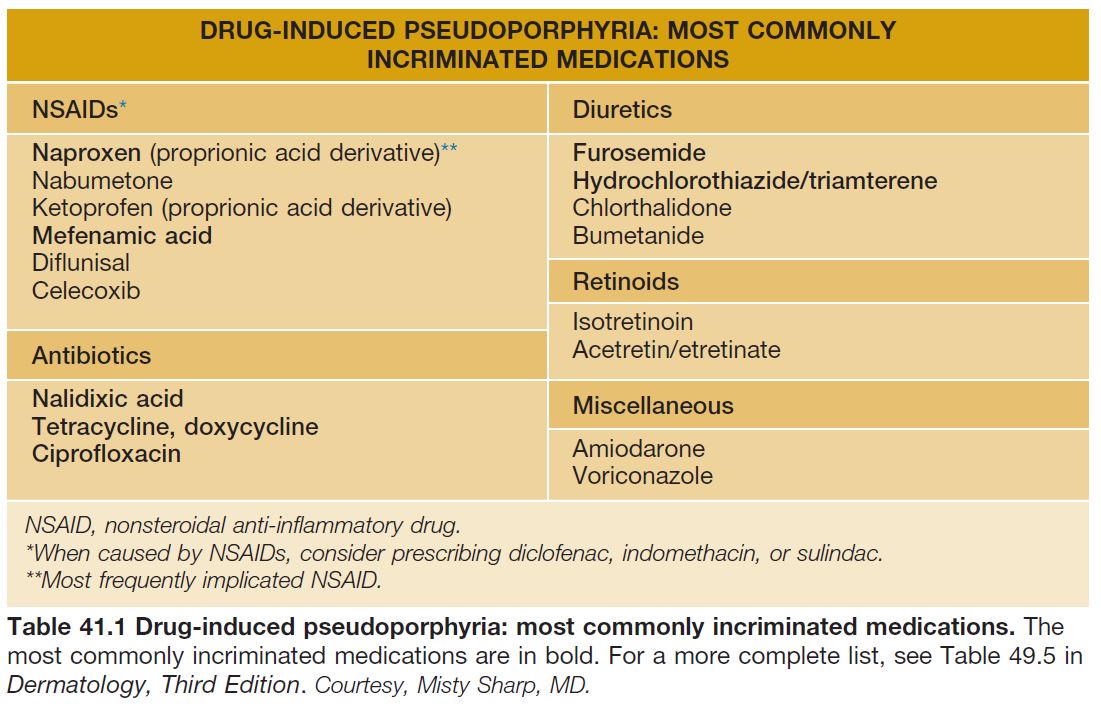

• DDx: pseudoporphyria due to medications (Table 41.1) or in patients with chronic kidney disease and those undergoing dialysis; phototoxic drug eruption; epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (sites of trauma but not limited to sun-exposed sites); rare forms of porphyria with similar cutaneous findings plus neurologic manifestations similar to acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) – variegate porphyria (see below) and hereditary coproporphyria (elevated coproporphyrins in feces consistently and in urine when symptomatic) – and mild forms of congenital erythropoietic porphyria.

• Rx: photoprotection via clothing and sunscreens containing titanium dioxide and zinc oxide (blocks visible light); avoidance of exacerbating factors; phlebotomy, initially 500 ml every 2–3 weeks, depending on the hematocrit; oral antimalarials, but at much lower doses than are used for cutaneous lupus erythematosus (LE), i.e. hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice weekly.

• In the setting of chronic kidney disease or renal dialysis and the associated anemia, the inability to use phlebotomy and/or antimalarials limits therapeutic options.

Erythropoietic Protoporphyria (EPP)

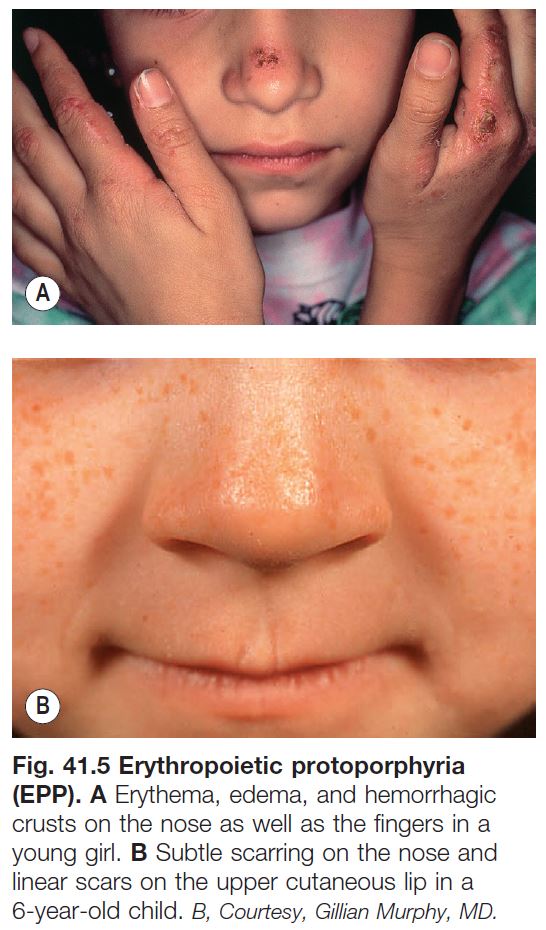

• Complaints of erythema, edema, and a painful burning sensation of the skin following sun exposure usually begin during early childhood; purpura and crusts may also be seen and over time, a waxy texture and scarring develop in areas of greatest cumulative UV exposure, i.e. on the nose and dorsal hands (Fig. 41.5).

• Inherited primarily in a semidominant pattern (mutation in one allele and specific polymorphism in second allele); internal manifestations include gallstones and cholestatic liver disease which can lead to liver failure (~5% of patients).

• Diagnosis is based on the detection of elevated levels of red blood cell (RBC) free protoporphyrins (lipophilic); elevated protoporphyrins are also present in the stool and genetic analysis can be performed; of note, zinc protoporphyrins are also elevated but this can be seen in other disorders, e.g. lead poisoning.

• DDx: solar urticaria, phototoxic or photoallergic contact dermatitis and drug reactions, hydroa vacciniforme, cutaneous LE, other causes of early onset photosensitivity (e.g. xeroderma pigmentosum, Rothmund–Thomson syndrome), and a very rare form of porphyria with similar cutaneous and hepatic findings – X-linked dominant protoporphyria.

• Rx: photoprotection (see PCT), β-carotene, α-melanotide; cholestyramine or charcoal, if liver disease.

Variegate Porphyria (VP)

• Rare form of porphyria, except in South Africa; autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

• While the cutaneous findings are similar to PCT, the systemic manifestations are similar to those of AIP, in particular acute attacks of abdominal pain, vomiting, paresthesias, motor and sensory neuropathies, and/or psychosis.

• Diagnosis is based on detection of elevated levels of urinary uro- and coproporphyrins (as in PCT) as well as elevated aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen (as in AIP), but these elevations may only be present during periods of symptomatic disease; elevated fecal porphyrins are present consistently and in the plasma, a characteristic peak fluorometric emission at 624–626 nm is observed in symptomatic patients; genetic analysis can also be performed.

• DDx: for cutaneous findings, PCT, pseudoporphyria, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (see PCT DDx).

• Rx: photoprotection (see PCT); avoidance of exacerbating factors (e.g. alcohol, fasting); for acute attacks, heme preparations.

Congenital Erythropoietic Porphyria (CEP)

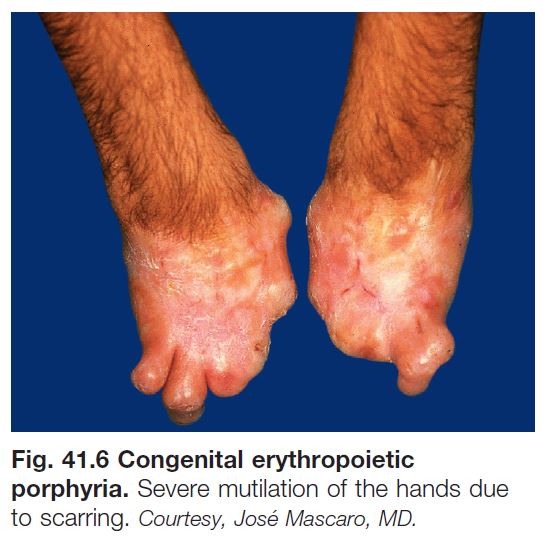

• Rare severe form of porphyria in which erythema, edema, blisters, erosions, and scarring, as well as hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis, develop in sun-exposed areas during infancy; autosomal recessive inheritance.

• Over time, the degree of scarring can become marked, leading to mutilation, e.g. mitten deformities of the hand (Fig. 41.6); additional manifestations include hemolytic anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, and pink-red urine stains and pink-red teeth (erythrodontia).

• Diagnosis is based on detection of elevated levels of uro- and coproporphyrins in the urine, RBCs, and plasma and elevated coproporphyrins in the stool; genetic analysis can also be performed.

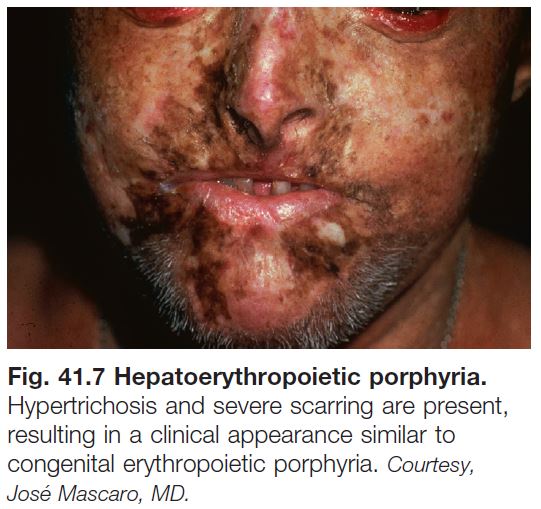

• DDx: hepatoerythropoietic porphyria, which represents the rare autosomal recessive variant of PCT (Fig. 41.7); other causes of early onset photosensitivity (see EPP above).

• Rx: strict photoprotection (see PCT), blood transfusions plus iron chelators such as oral deferasirox, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Pseudoporphyria (Pseudo-PCT, Bullous Dermatosis of Dialysis)

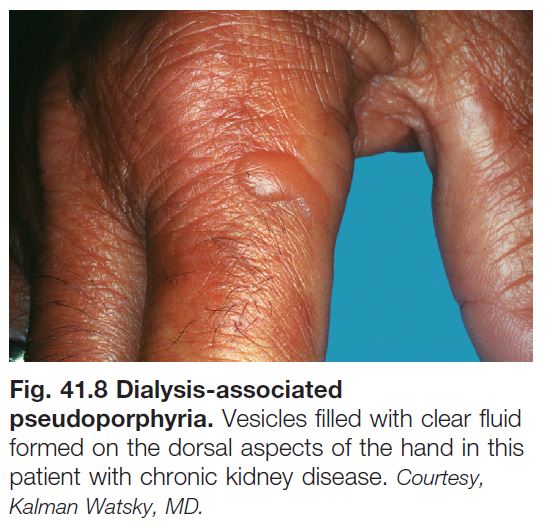

• Clinical presentation similar to PCT but without abnormal elevation of porphyrins, although patients with renal disease can have borderline elevations in porphyrin levels.

• Seen in patients with chronic kidney disease and those undergoing dialysis, usually hemodialysis (Fig. 41.8); it is also associated with certain medications (Table 41.1).

• Can also occur following tanning bed use.

• DDx: see PCT.

• Rx: discontinue suspect drug; photoprotection (see PCT).