General

• A multisystem AI-CTD disorder that prominently affects the skin.

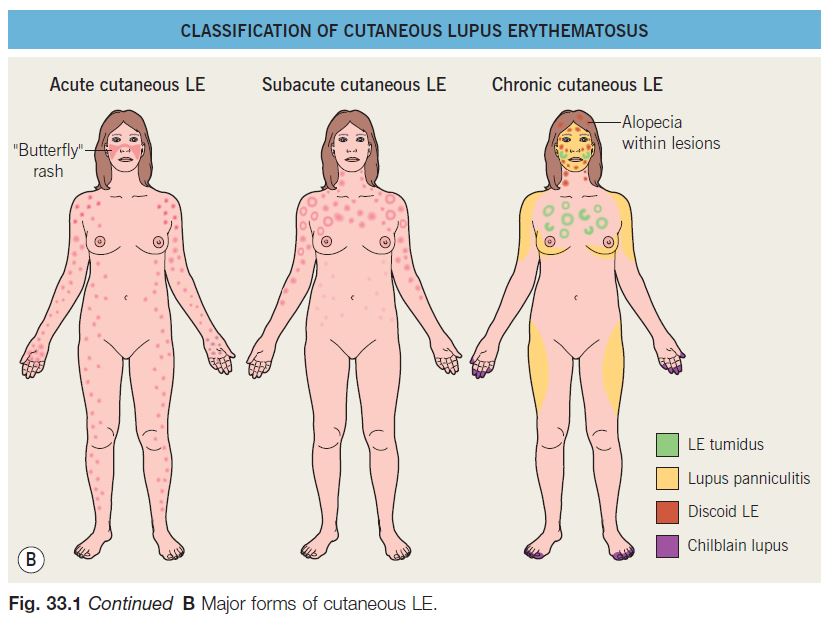

• Broadly divided into systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), and drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DI-LE) (Fig. 33.1).

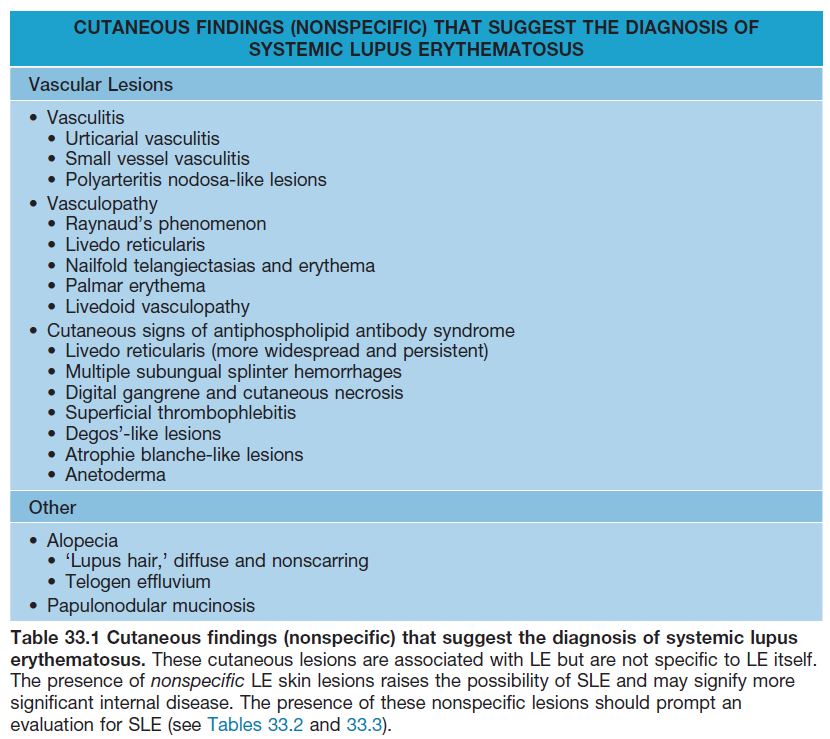

• CLE is further classified into specific and nonspecific skin lesions, based on the histopathologic presence (specific) or absence (nonspecific, Table 33.1) of an ‘interface dermatitis’; however, this is not a perfect classification scheme because some specific entities (e.g. LE tumidus, lupus panniculitis) do not demonstrate an ‘interface dermatitis’ and other, nonlupus entities may display an ‘interface dermatitis’ on histopathology (e.g. dermatomyositis).

• Classically, the three major forms of specific skin lesions are chronic cutaneous LE (CCLE), subacute cutaneous LE (SCLE), and acute cutaneous LE (ACLE), with CCLE being subdivided into four different entities (see Fig. 33.1).

• Cutaneous lesions may be the sole manifestation of LE or they may be associated with systemic disease (SLE), either concurrently or sequentially.

• For all types of LE: women > men; African Americans or black Africans > other populations; onset typically post-puberty to middle age.

• Histopathologic examination of cutaneous lesions often plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis of CLE; direct immunofluorescence of lesional skin can be helpful in distinguishing CLE from other disorders, in particular lichen planus; accurate subtyping requires clinicopathologic correlation.

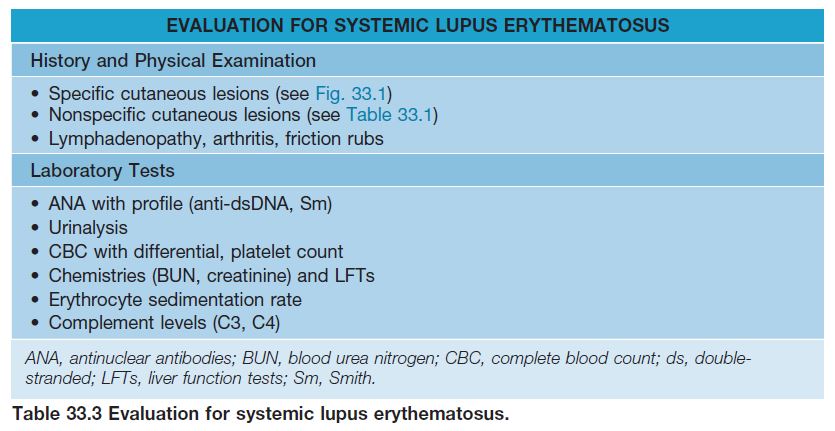

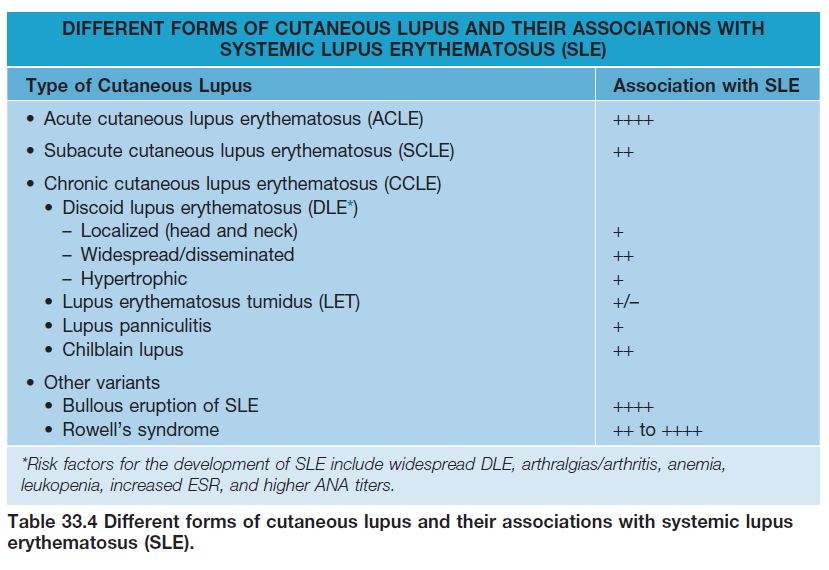

• Once a diagnosis of CLE is made, initial and longitudinal evaluation for systemic manifestations of SLE is recommended (Tables 33.2–33.4).

• Before making a definitive diagnosis of cutaneous lupus, it is necessary to exclude a drug-induced etiology (Table 33.5).

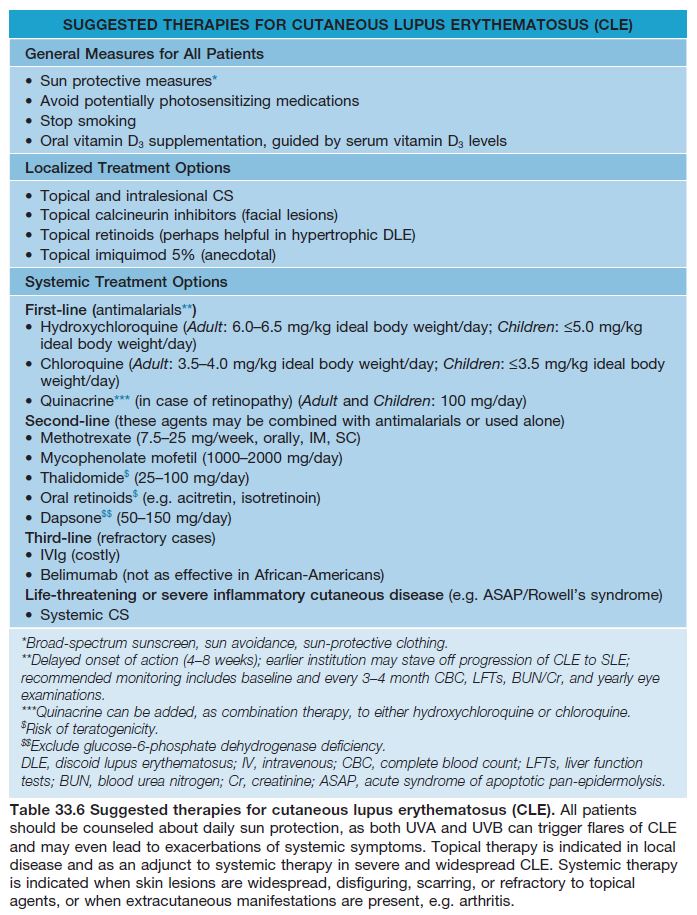

• Treatment options for the various subtypes of CLE are fairly similar (Table 33.6).

Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus

• There are two major forms: drug-induced SLE (DI-SLE) and drug-induced SCLE (DISCLE); skin lesions are indistinguishable from classic, non-drug-related LE (see Table 33.5).

• Attention should be given to those medications that were initiated within weeks to 9 months prior to the onset of the eruption.

• Usually resolves upon discontinuation of the responsible medication along with sun protection and topical therapy; occasionally a patient will require systemic therapy for persistent disease.

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus: Specific Lesions

Chronic Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CCLE)

DISCOID LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS (DLE)

• Most common skin manifestation of LE; the terms CCLE and DLE are often used interchangeably, but CCLE encompasses four entities (see Fig. 33.1).

• Overall, ~5–10% of patients will go on to develop SLE (see Table 33.4), but DLE can be a presenting manifestation of SLE.

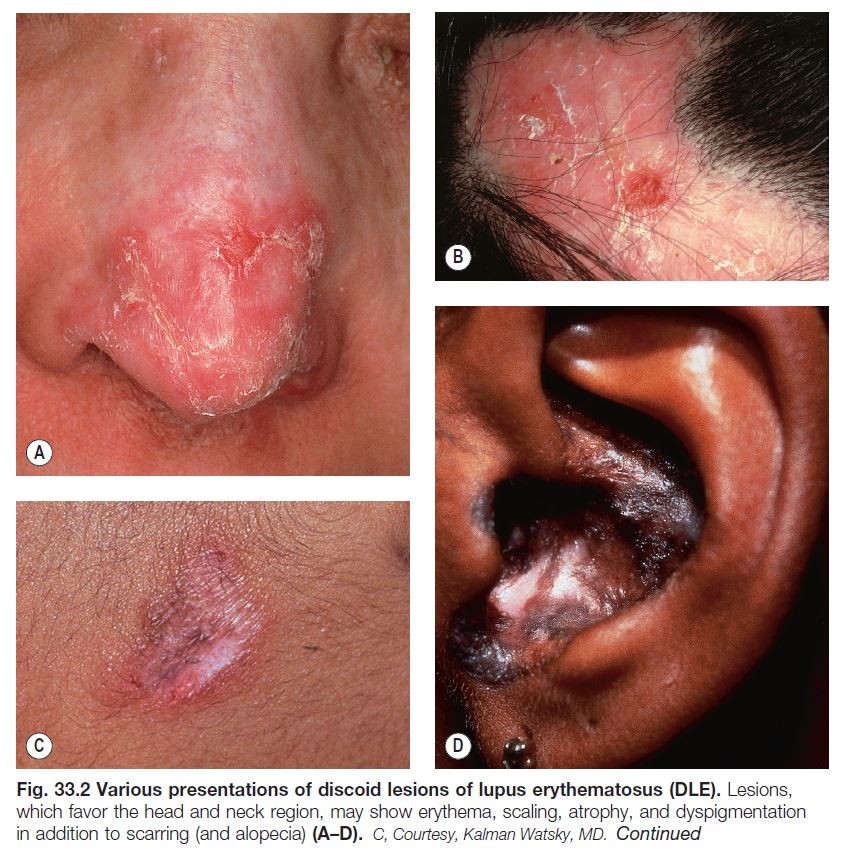

• Three clinical variants of DLE are recognized.

– Localized: Most common; involves the head and neck region; ≤5% risk of progression to SLE.

– Widespread: Lesions extend beyond the head and neck region to involve the extremities and/or trunk; up to 20% of patients can progress to SLE.

– Hypertrophic: Unusual variant; favors extensor arms > face, upper trunk (Fig. 33.2H); thick scale overlying or at periphery of DLE lesions; may resemble hypertrophic actinic keratoses, SCC, hypertrophic lichen planus, or prurigo nodularis.

• Occasionally can involve mucosal surfaces, palms and soles (see Fig. 33.2F,G).

• May occur in sun-exposed or sun-protected sites (e.g. scalp).

• Early lesions: inflamed, indurated plaques with erythema and scale.

• Well-established lesions: typically display follicular plugging, atrophy, scarring (and alopecia), and dyspigmentation (see Fig. 33.2A–E); the follicular plugging is often best appreciated in the conchal bowl of the ear.

• DDx: Early lesions: Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, polymorphic light eruption (PMLE), lymphocytoma cutis, lymphoma cutis, granuloma faciale, sarcoidosis; Late lesions: lichen planus (hypertrophic, palmoplantar and mucosal variants), sarcoidosis.

• Typical Rx: high-potency topical CS, intralesional CS (5 mg/cc), and/or antimalarials (see Table 33.6).

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS (LE) TUMIDUS

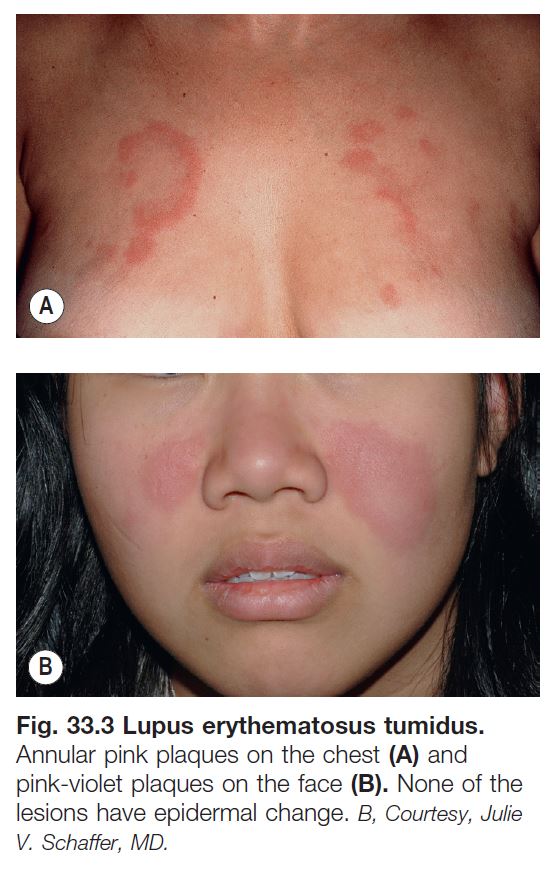

• LE tumidus is an entity that overlaps with Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate and reticular erythematous mucinosis (REM); there is debate as to whether it is a distinct entity or whether it should be considered a specific type of lupus.

• Photo-induced, but often this is not appreciated because of the delay of 1–2 weeks between UVR exposure and onset of the eruption.

• Most common on the face and upper trunk; reportedly <1% of patients eventually develop SLE.

• Lesions characterized by erythema, induration, and often central clearing (Fig. 33.3); scale, follicular plugging, scarring, and atrophy are absent.

• DDx: Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, PMLE, REM (chest lesions), papulonodular mucinosis.

LUPUS PANNICULITIS (See Chapter 83)

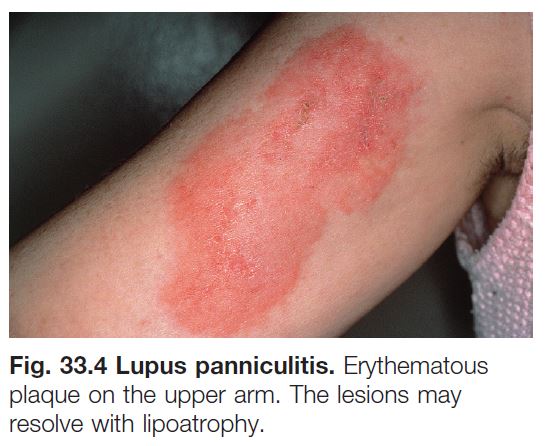

• Initially characterized by intense inflammation in the subcutaneous fat; eventuates into lipoatrophy.

• The most common sites of involvement are the face, upper outer arms, upper trunk, breasts, buttocks, and thighs, with the majority representing sites of abundant fat (Fig. 33.4).

• Sometimes overlying DLE lesions are seen (termed ‘lupus profundus’).

CHILBLAIN LUPUS (SLE PERNIO)

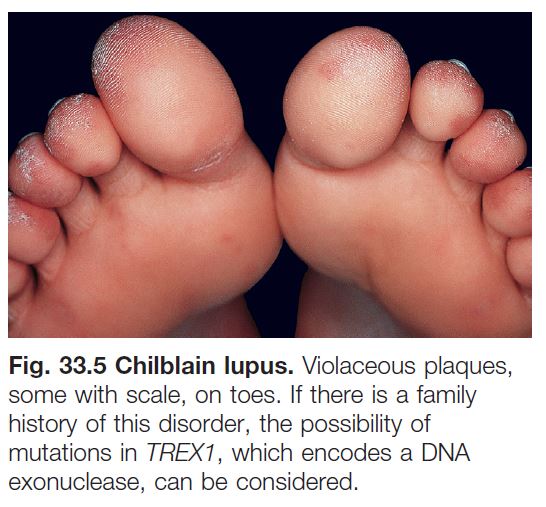

• Typically presents with erythematous to dusky purple papulonodules and plaques on the toes, fingers > nose, elbows, knees, and lower legs (Fig. 33.5).

• Lesions are triggered or exacerbated by cold temperatures, often in combination with damp conditions.

• With time, some lesions may progress to resemble DLE both clinically and histopathologically.

• DDx: idiopathic chilblains (following exclusion of SLE), familial chilblain lupus (TREX1 mutation), other cold-induced syndromes (see Chapter 74).

• Up to 20% of patients may go on to develop SLE.

Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (SCLE)

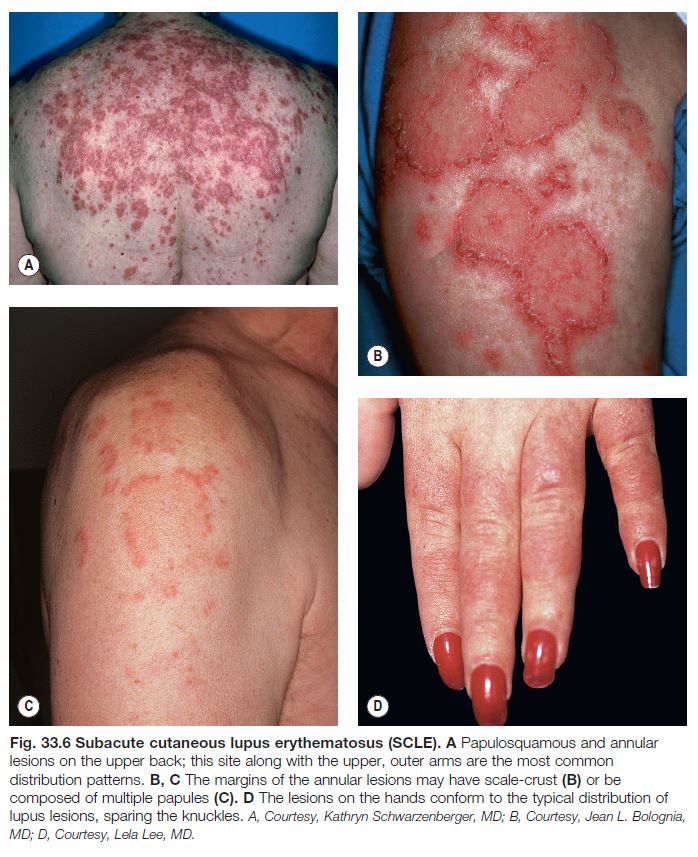

• Characterized by non-scarring, annular, or papulosquamous eruptions in photodistributed sites (Fig. 33.6).

• Favors the upper trunk and upper outer arms > lateral neck, forearms, hands (see Fig. 33.6).

• Interestingly, often spares the mid-face.

• Two common clinical presentations are recognized.

– Annular: raised erythematous borders with central clearing (see Fig. 33.6B, C).

– Papulosquamous: psoriasiform or eczematous appearance (see Fig. 33.6A).

• Long-term residual changes include

dyspigmentation (most often hypo- to depigmentation).

• Approximately 10–15% of patients may over time develop SLE (see Table 33.4).

• Depending on the laboratory, ~70% of patients have associated anti-Ro/SSA antibodies.

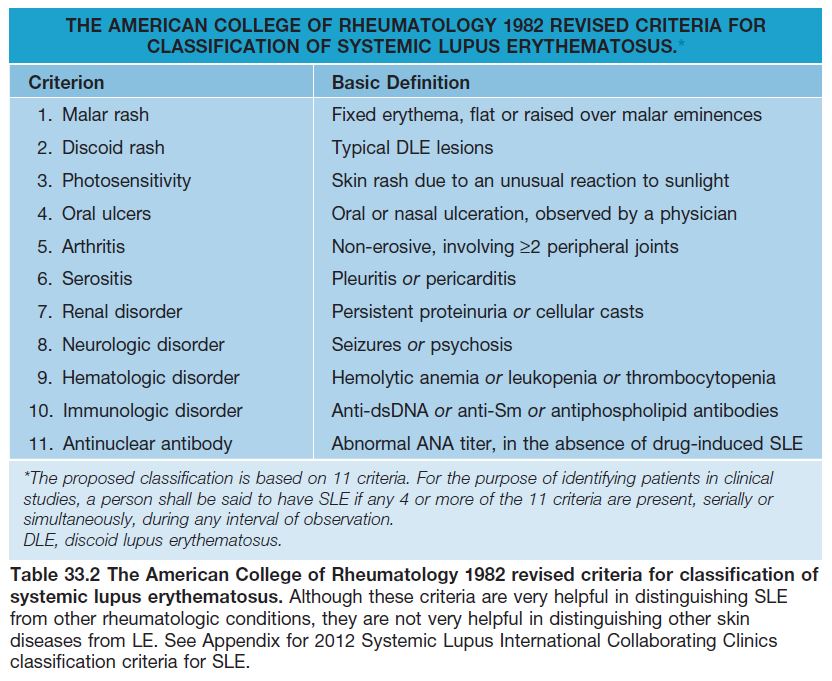

• Roughly 50% of patients fulfill ≥4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for SLE (see Table 33.2), but they rarely develop serious systemic involvement; arthralgias most common.

• DDx: Annular variant: dermatophytosis, granuloma annulare, erythema annulare centrifugum, or other annular erythemas (see Chapter 15); Papulosquamous variant: photo-lichenoid drug reaction (e.g. HCTZ, antimalarials), psoriasis, photoexacerbated eczema, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD),

lichen planus, PMLE.

• Before a diagnosis of classic SCLE can be made, exclude the possibility of DI-SCLE (see Table 33.5).

NEONATAL SCLE (NLE)

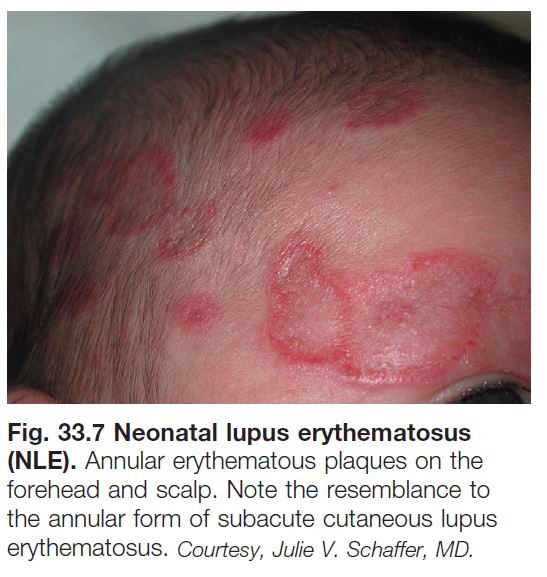

• Occurs in infants whose mothers have anti-Ro/SSA autoantibodies that are passively transferred to the fetus.

• These infants primarily have anti-Ro/SSA antibodies (>98%), but may also have anti-La/SSB or anti-U1RNP antibodies.

• Approximately 1–5% of mothers with anti-Ro/SSA antibodies will have infants with NLE, with risk increasing to 10–25% with subsequent pregnancies.

• Cutaneous lesions are similar to adult SCLE but favor the face and periorbital areas and may be atrophic (Fig. 33.7).

• Photosensitivity is common but sun exposure is not necessary for lesion formation.

• New lesions typically cease to develop by 6–9 months of age, i.e. once the antibodies are cleared; however, there may be residual changes such as dyspigmentation and telangiectasias.

• The most common internal manifestations are (1) congenital heart block (± associated cardiomyopathy); (2) hepatobiliary disease; (3) thrombocytopenia > neutropenia or anemia; (4) macrocephaly or skeletal dysplasia.

• Heart block, if it is going to occur, is almost always present at birth and a pacemaker is often required.

• If skin signs of NLE are present, an evaluation, including physical examination, ECG ± echocardiogram, CBC, and liver function tests, is indicated; the latter laboratory tests should be repeated periodically over the first 6 months of life.

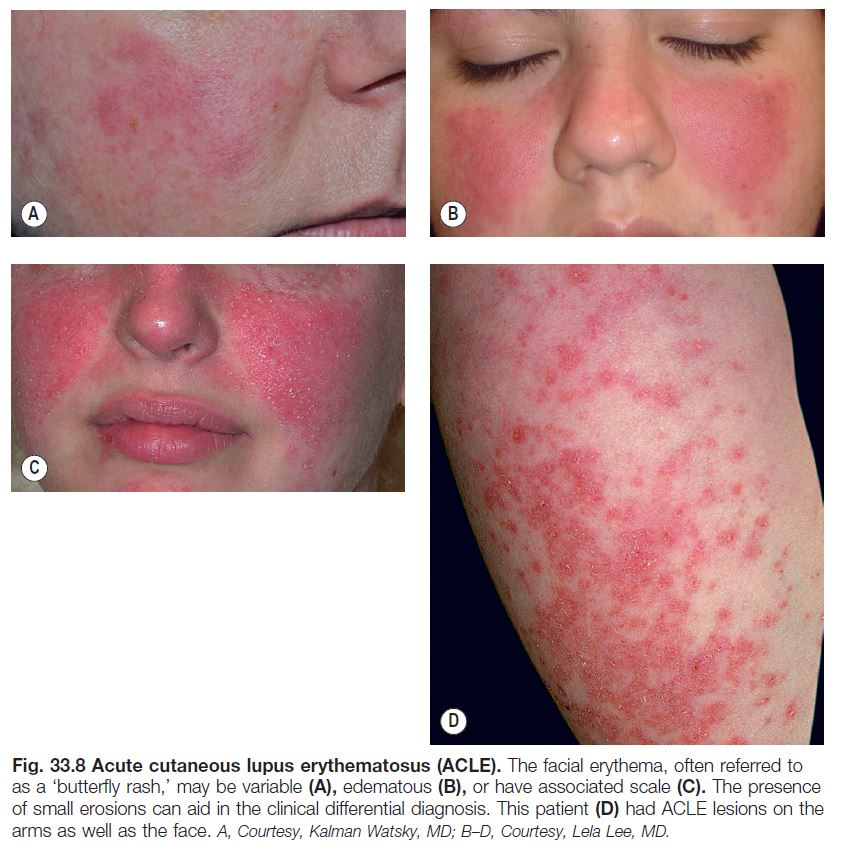

Acute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (ACLE)

• The CLE variant most closely associated with SLE and if diagnosed the patient should be evaluated for internal disease.

• Three clinical presentations are recognized:

– Facial (malar): the classic ‘butterfly’ eruption, presenting with symmetric erythematous patches or more infiltrated plaques over the nasal bridge and cheeks; spares nasolabial folds (Fig. 33.8A–C).

– Photodistributed: exanthematous to urticarial eruption involving primarily UV-exposed skin, e.g. upper chest, extensor arms (Fig. 33.8D), dorsal hands (with sparing of the knuckles).

– Widespread: extends beyond photodistributed sites.

• A particular patient’s ACLE clinical presentation will often repeat itself with subsequent flares, representing a ‘signature’ pattern.

• Lesions typically respond to systemic CS and resolve without scarring; may leave residual dyspigmentation.

• DDx: Facial: seborrheic dermatitis, rosacea, sunburn, perioral dermatitis, tinea faciei, cellulitis, contact dermatitis; Photodistributed: drug-induced photosensitivity, dermatomyositis; Widespread: exanthem (viral or drug-induced).

Other

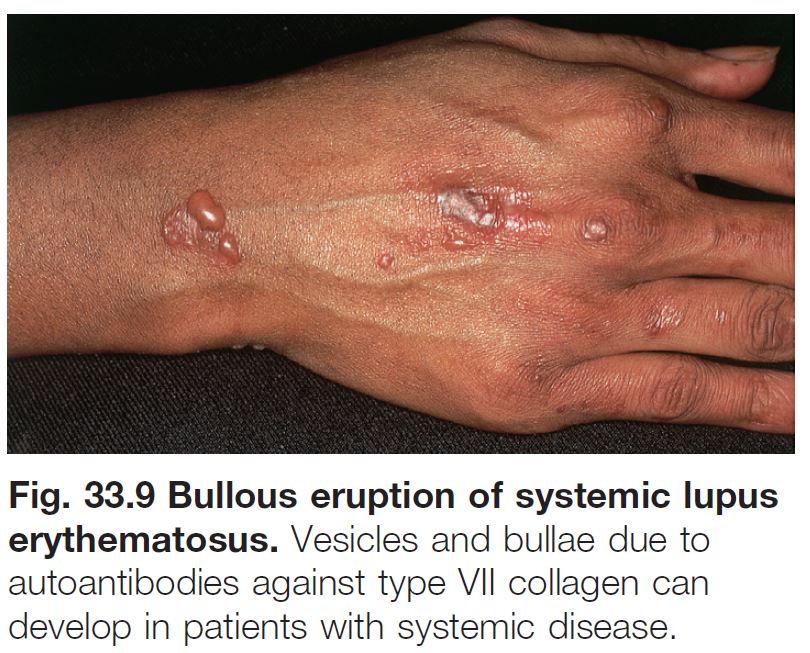

BULLOUS ERUPTION OF SLE

• Clinically presents as blisters (ranging from tiny vesicles to large tense bullae) on an erythematous base, typically involving the face, neck, upper trunk, proximal extremities, and mucosal surfaces; seen in patients with underlying SLE (Fig. 33.9).

• Autoantibodies against type VII collagen are present.

• DDx: Clinical: autoimmune blistering diseases, contact dermatitis, acute syndrome of apoptotic pan-epidermolysis (ASAP); Histopathological: dermatitis herpetiformis.

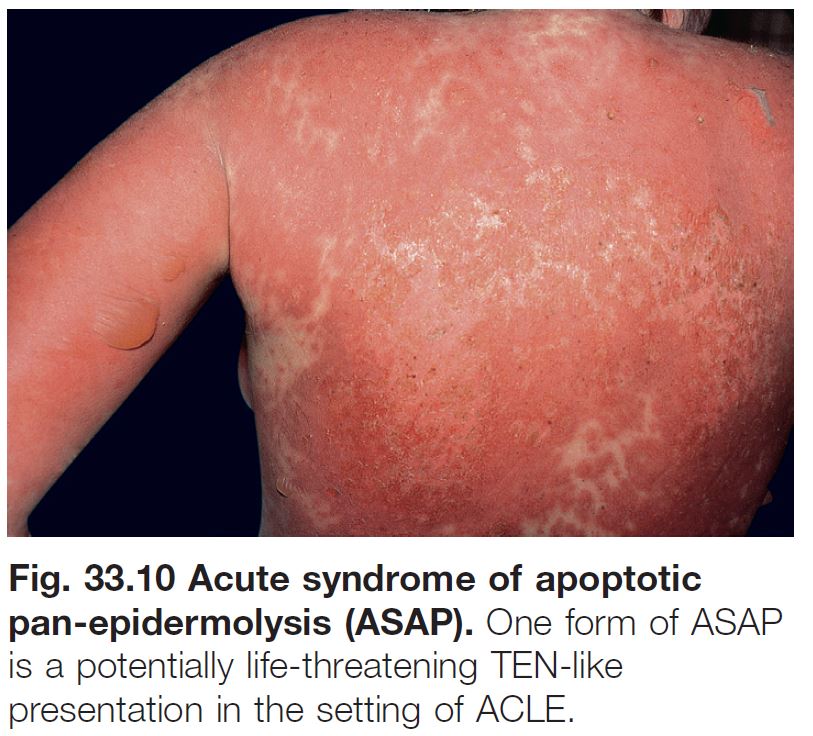

ACUTE SYNDROME OF APOPTOTIC PAN-EPIDERMOLYSIS (ASAP)/ ROWELL’S SYNDROME

• The term ASAP embraces various entities in which there is acute and widespread epidermal cleavage resulting from hyperacute apoptotic injury of the epidermis from various causes (e.g. drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis [TEN], TEN-like GVHD, and TEN-like ACLE).

• Rowell’s syndrome and TEN-like ACLE are thought to occur along a spectrum of ASAP, with the former representing a less severe erythema multiforme major-like presentation in the setting of lupus and the latter a potentially life-threatening TEN-like presentation in the setting of ACLE (Fig. 33.10).

• This spectrum of cutaneous findings may occur de novo or in the setting of rebound ACLE or SCLE; significant internal organ involvement (e.g. kidney and CNS) is common.

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus: Nonspecific Lesions

• A variety of cutaneous lesions not entirely specific to LE may be seen, signaling not only internal organ involvement (SLE) but also increased systemic disease activity (see Table 33.1).

VASCULAR LESIONS AND THE ANTIPHOSPHOLIPID ANTIBODY SYNDROME (APL)

• Vascular lesions and APL are common in patients with LE, especially those with SLE (see Table 33.1).

• Approximately one-third of APL cases occur in the setting of lupus (see Chapter 18); compared to primary APL, these patients are more likely to have arthritis, livedo reticularis (LR), and cytopenias.

• Patients with LE and APL may benefit from antimalarial therapy.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

• The organ systems most commonly involved are the joints, skin, hematologic, lungs, kidneys, and CNS, which in large part are reflected in the ACR criteria for SLE diagnosis (see Table 33.2); however, this list is not exhaustive and clinical judgment is required.

• In individual patients it is often only one or a few organs that are significantly affected.

• ACLE is the specific CLE variant most closely associated with SLE, but patients with any type of CLE may develop internal involvement (SLE) (see Table 33.4).

• Indicators of an increased risk for SLE in patients presenting with CLE include fever, weight loss, fatigue, myalgia, lymphadenopathy, and nonspecific skin findings (see Table 33.1).

• The basic evaluation for SLE is highlighted in Table 33.3, and it is important to exclude drug-induced SLE (see Table 33.5).

• A negative ANA is helpful because it is highly unlikely that a patient with a negative ANA has SLE.

• A positive ANA is less helpful, as it may occur in normal individuals (usually at low titers) and in patients with CLE.

• Specific antibodies to SLE include dsDNA and Sm.