• Common pilosebaceous disorder that occurs in ~85% of individuals 12–24 years of age and 15–35% of adults (especially women) in their 30s–40s.

• Clinical presentations range from mild comedones to severe, explosive eruptions of suppurative nodules associated with systemic manifestations.

• May result in scarring and psychosocial repercussions such as anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal.

• A tendency to develop moderate to severe acne can run in families.

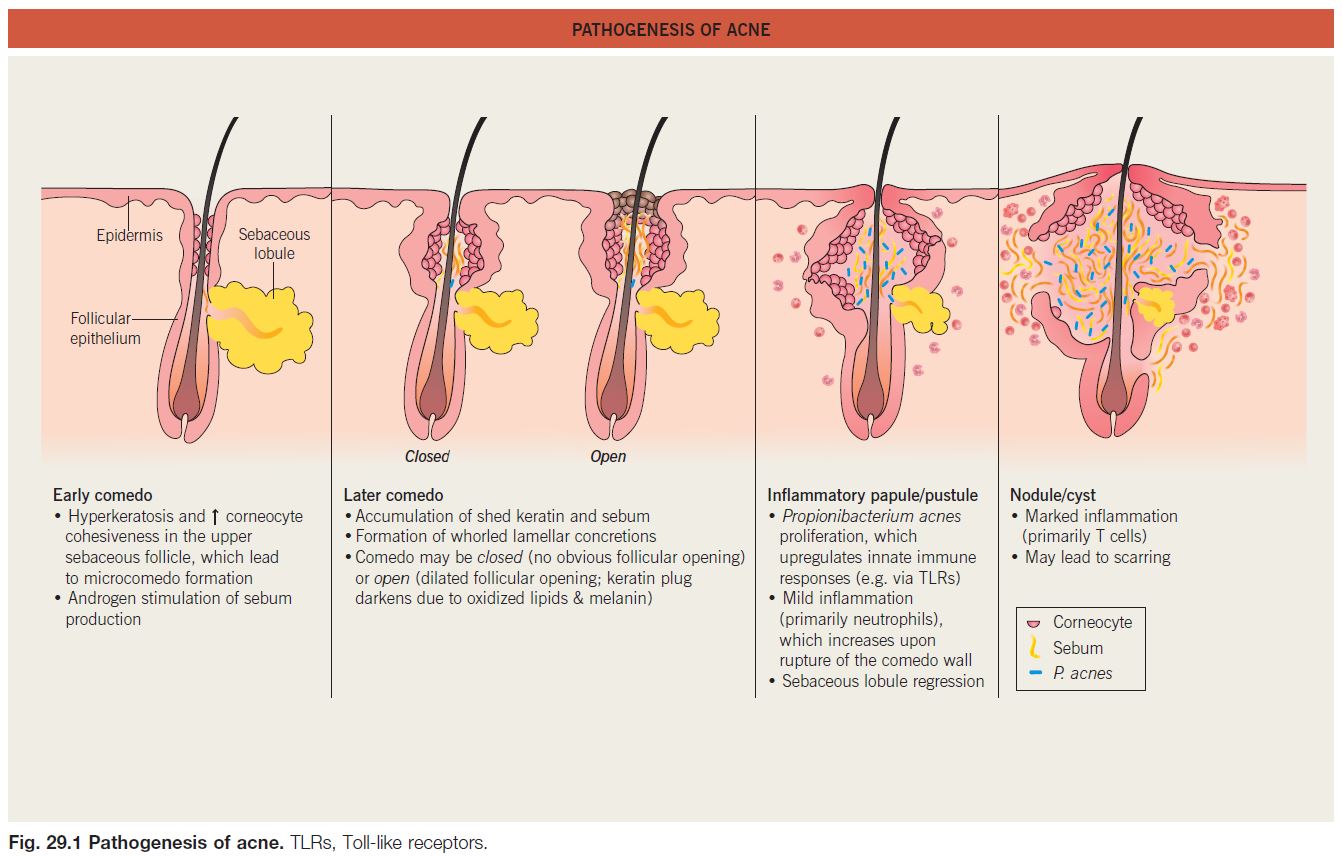

• Multiple factors affecting the pilosebaceous unit contribute to acne pathogenesis (Fig. 29.1), a process that typically begins when androgen production increases at adrenarche.

• The relationship between diet and acne is controversial, with some evidence of possible associations with milk intake (especially skim milk) and a high glycemic index diet.

Clinical Features and Variants of Acne

• Favors the face and upper trunk, sites with well-developed sebaceous glands.

• Non-inflammatory acne.

– Closed comedones (whiteheads) are small (~1 mm), skin-colored papules without an obvious follicular opening (Fig. 29.2A,B).

– Open comedones (blackheads) have a dilated follicular opening filled with a keratin plug, which has a black color due to oxidized lipids and melanin (Fig. 29.2B,C).

• Inflammatory acne.

– Erythematous papules and pustules (Fig. 29.3A).

– Nodules and cysts filled with pus or serosanguinous fluid; may coalesce and form sinus tracts (Fig. 29.3B).

– Acne conglobata (severe nodulocystic acne) is classified in the follicular occlusion tetrad along with dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pilonidal cysts (see Chapter 31); it is also a part of pyogenic

arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne conglobata (PAPA) and pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndromes.

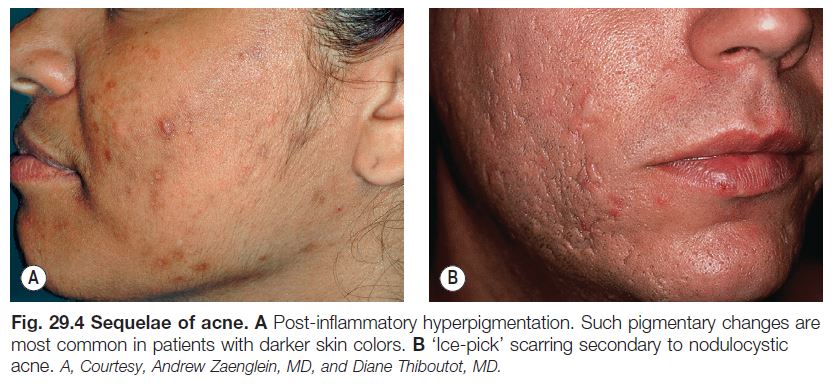

• Inflammatory acne commonly results in post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, especially in patients with darker skin, which fades slowly over time (Fig. 29.4A); nodulocystic acne (and less frequently other inflammatory > comedonal forms) often leads to pitted (Fig. 29.4B) or hypertrophic scars (the latter especially on the trunk; see Fig. 81.4).

Post-Adolescent Acne

• Age >25 years; favors women.

• Tends to flare in the week prior to menstruation; up to one-third of these women have hyperandrogenism.

• Typically features papulonodules on the lower face, jawline, and neck.

Acne Excoriée

• Favors teenage girls and young women.

• Habitual picking at comedones and inflammatory papules, resulting in crusted erosions (often linear/angular) and potential scarring (see Fig. 5.3).

• Some patients have an underlying obsessive–compulsive or anxiety disorder.

Acne Fulminans

• Favors boys 13 to 16 years of age.

• Sudden development of numerous, markedly inflamed nodular lesions on the face, trunk, and upper arms.

• Coalescence into painful, oozing, friable plaques with hemorrhagic crusting, erosion/ ulceration, and eventual scarring (Fig. 29.5).

• Systemic manifestations include fever, malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, osteolytic bone lesions (most often of clavicles and sternum), and hepatosplenomegaly.

• Laboratory findings: leukocytosis and increased ESR > anemia, microscopic hematuria, and proteinuria.

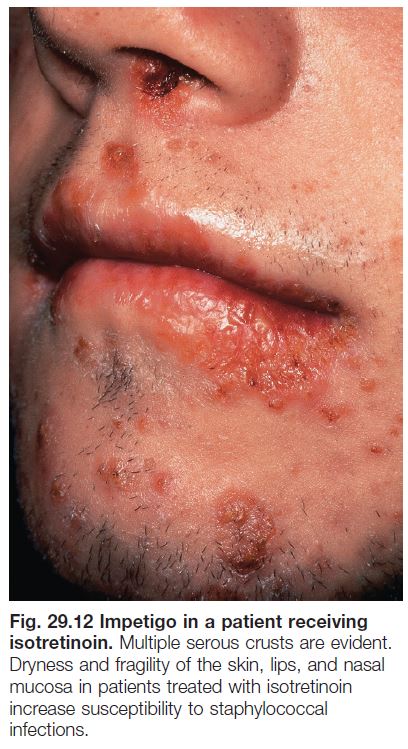

• DDx: an acne fulminans-like flare occasionally develops upon initiation of isotretinoin therapy for acne, and acne fulminans can be associated with synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome

(see Chapter 21).

• Rx: isotretinoin (low dose initially with slow escalation) plus prednisone.

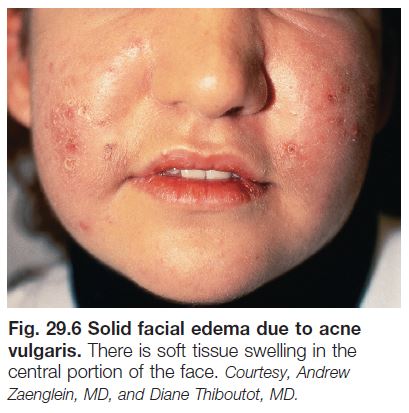

Solid Facial Edema (Morbihan’s Disease)

• Woody induration ± erythema of the central face in the setting of chronic inflammation due to acne vulgaris or rosacea (Fig. 29.6).

• Rx: isotretinoin (may require an extended course).

Neonatal Acne (Neonatal Cephalic Pustulosis) (See Chapter 28)

• Ages 2 weeks to 3 months.

• Facial papulopustular eruption thought to be triggered by Malassezia spp.; comedones are not present.

Infantile Acne

• Ages 3 months to 2 years; favors boys.

• Facial comedones, papulopustules, and cysts as in classic acne (Fig. 29.7); may result in scarring.

• Reflects physiologic elevation of androgen levels in infants 6–12 months of age (especially boys); patients often have a family history of severe acne.

• Rx: similar to adolescent acne; typically resolves within 1–2 years, becoming quiescent until puberty.

Contact Acne

• Acne mechanica: comedogenesis due to chronic friction/occlusion from objects such as chin straps, helmets, collars, and musical instruments (e.g. ‘fiddler’s neck’ in a violinist).

• Acne cosmetica, pomade acne, and occupational acne: comedogenesis caused by exposure to follicle-occluding substances in cosmetics, hair products (favoring forehead and temples), and materials used in the workplace (e.g. cutting oils, coal tar derivatives).

Chloracne

• Results from exposure (usually occupational) to halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g. polychlorinated dibenzodioxins and dibenzofurans) in agents such as herbicides and insecticides.

• Comedones and cystic papulonodules develop within 2 months of exposure, favoring malar and retroauricular areas of the face (see Fig. 12.18) as well as the axillae and scrotum; often persists for years.

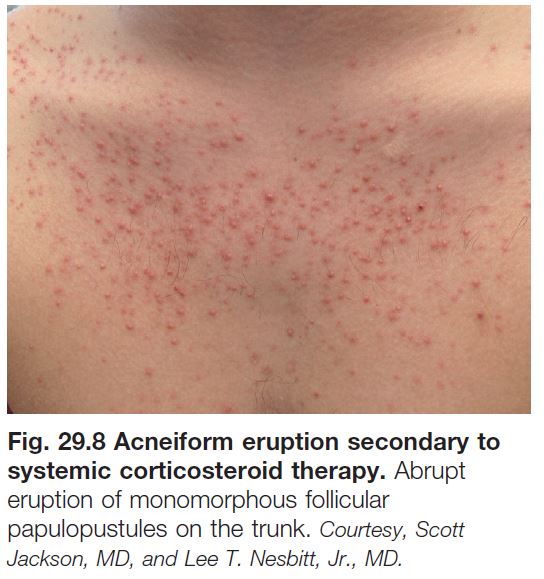

Drug-Induced Acne and Acneiform Eruptions

• Systemic CS can trigger an eruption of monomorphous follicular papulopustules favoring the upper trunk (Fig. 29.8).

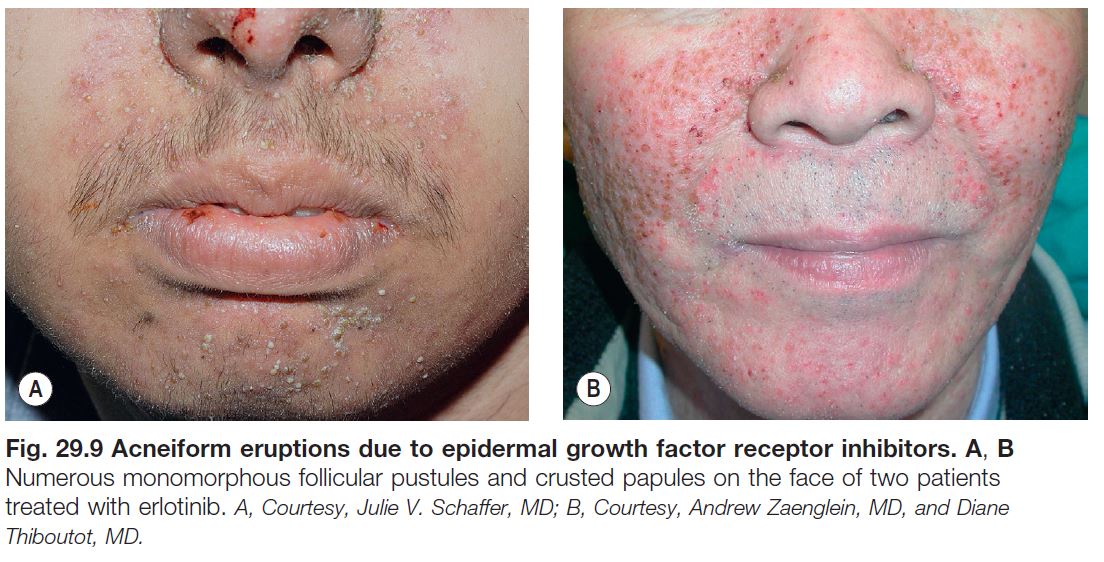

• Acneiform eruptions represent a frequent side effect of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors (e.g. cetuximab, erlotinib) used to treat solid tumors; patients present with follicular pustules and papules on the face (Fig. 29.9), scalp, and upper trunk, usually 1–3 weeks after beginning treatment, which may correlate with a therapeutic response.

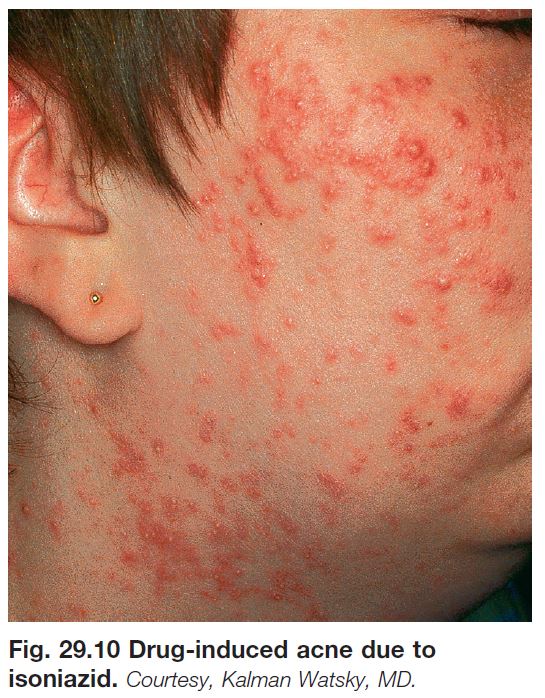

• Other common causes of drug-induced acne include anabolic steroids, bromides (found in sedatives and cold remedies), iodides (found in contrast dyes and supplements), isoniazid (Fig. 29.10), lithium, phenytoin, and progestins.

Acne Associated with a Syndrome

• Examples include Apert, PAPA, PASH, and SAPHO (see Ch. 21) syndromes.

Evaluation and Treatment of Acne

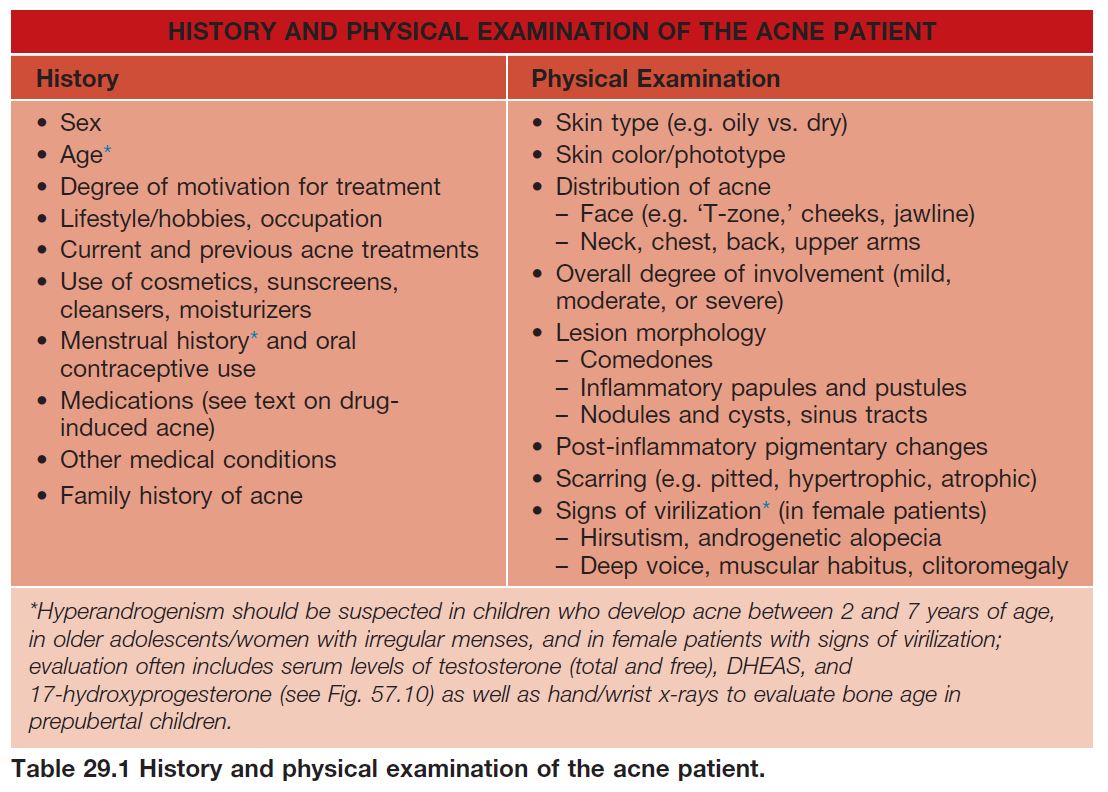

• Table 29.1 lists key components in the

history and physical examination of an acne patient.

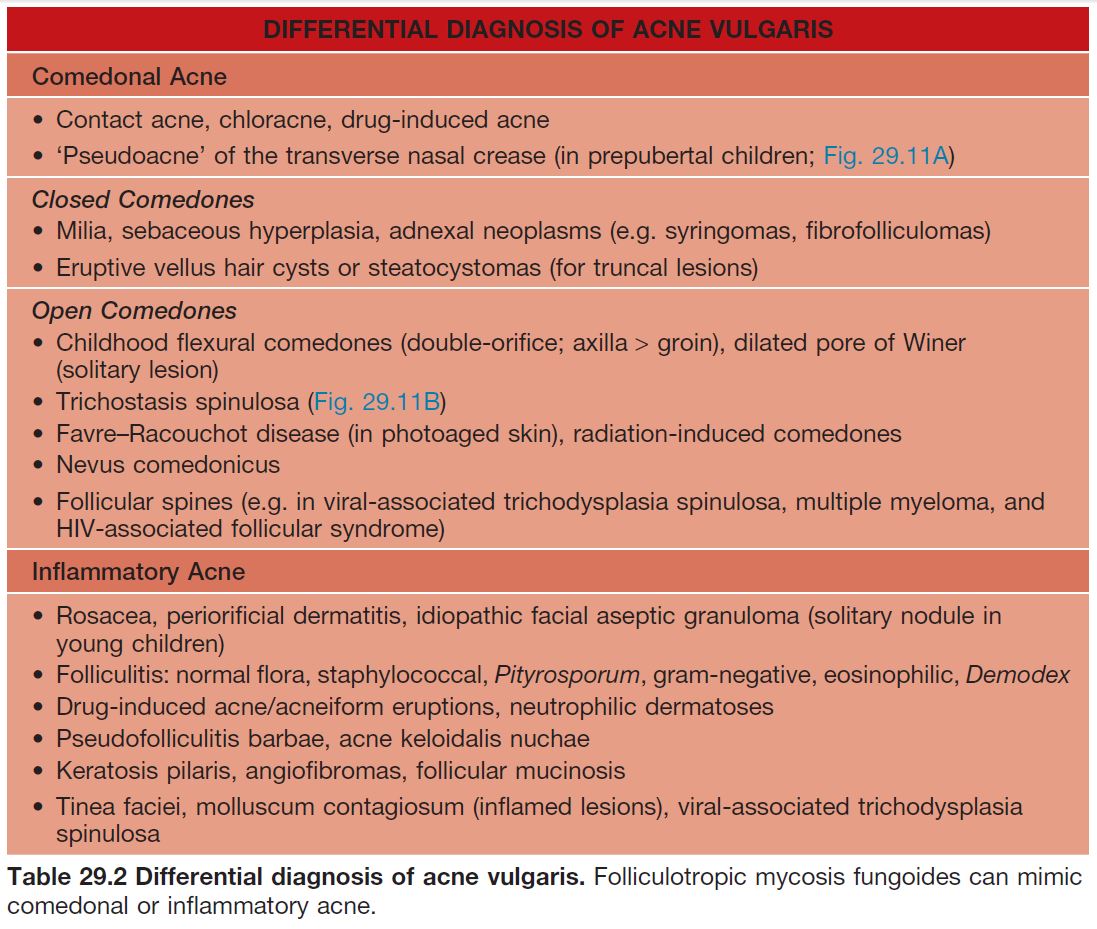

• DDx: presented in Table 29.2.

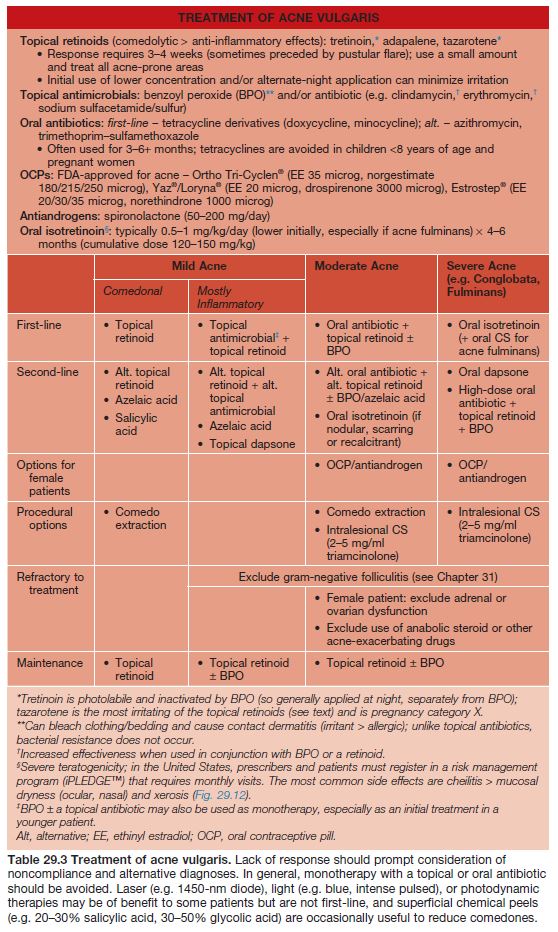

• Rx: outlined in Table 29.3.

• Once active acne has been successfully treated, intralesional CS (for hypertrophic scars) or surgical modalities (e.g. fractional or traditional laser resurfacing, dermabrasion, fillers) can be used for residual scarring if needed.

Tips for Topical Therapy

• Lack of compliance is often an issue, with common reasons including irritated skin, busy schedules, and giving up when the response is not rapid; substantial benefit typically requires 6–8 weeks of treatment.

• The main side effect of topical medications is irritation, which is most problematic in adolescents with atopic dermatitis and adults.

• Patients should be advised to avoid harsh scrubs, other irritating agents (e.g. toners, acne products that are not part of the regimen), and manipulation of lesions, especially inflammatory papulonodules and closed comedones.

• Even if planning combination therapy, a gradual initial approach can improve tolerance in patients with sensitive skin; for example, a single agent may be used for the first 2–3 weeks (starting every other day for retinoids), followed by slow introduction of a second medication (e.g. transitioning from alternate days to daily).

• Simplifying the regimen and considering combination products (e.g. benzoyl peroxide + adapalene or clindamycin; tretinoin + clindamycin) may improve compliance, especially in less-motivated adolescents.

• In general, topical medications (especially retinoids) should be used to the entire acne-prone region rather than as ‘spot treatment’ of individual lesions.

• Patients should be instructed to select noncomedogenic products (e.g. moisturizers, sunscreens, make-up) and to avoid having oily hair or using pomades that may contribute to acne.

• Having patients bring everything that they apply to their face to a visit may help to determine the source of problems.