• Purpura represents visible hemorrhage into the skin or mucous membranes; as a result and in contrast to erythema due to vasodilation, it is nonblanching upon application of external pressure.

• Purpura can be primary, where hemorrhage is an integral part of lesion formation, or secondary, where there is hemorrhage into established lesions due to factors such as venous hypertension, gravity, or thrombocytopenia.

• As purpuric lesions fade, their color evolves from red-purple or blue to brown or yellow-green.

• Primary purpura has a broad differential diagnosis, and it is helpful to categorize purpuric lesions based on their size and morphology.

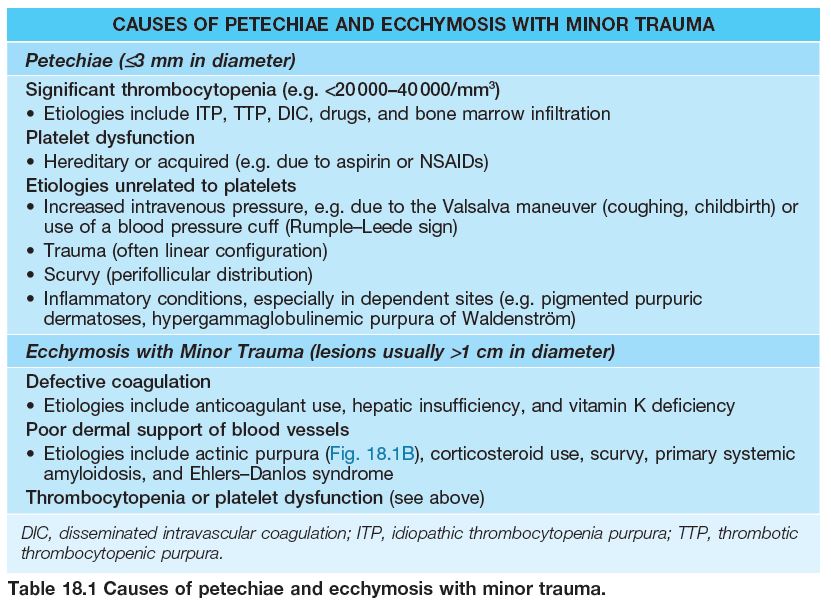

– Petechiae: ≤3 mm and macular (Table 18.1; Fig. 18.1A).

– Ecchymoses: usually >1 cm and macular with round/oval to slightly irregular borders, and typically have an element of trauma in their pathogenesis (see Table 18.1; Fig. 18.1B); a greater volume of hemorrhage leads to a hematoma, which is palpable.

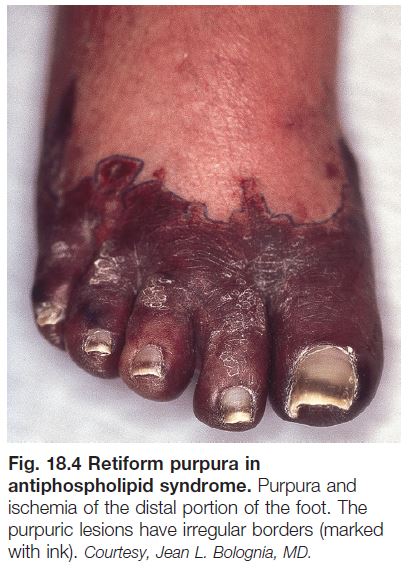

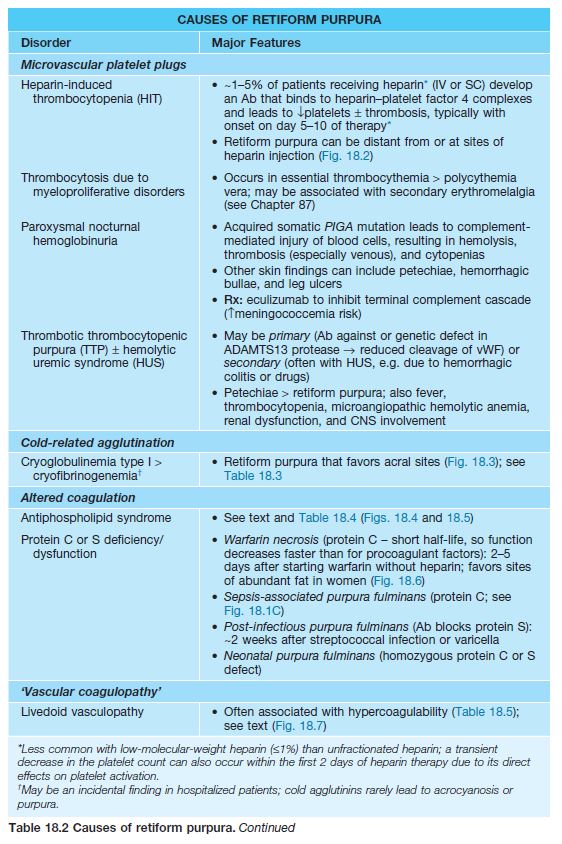

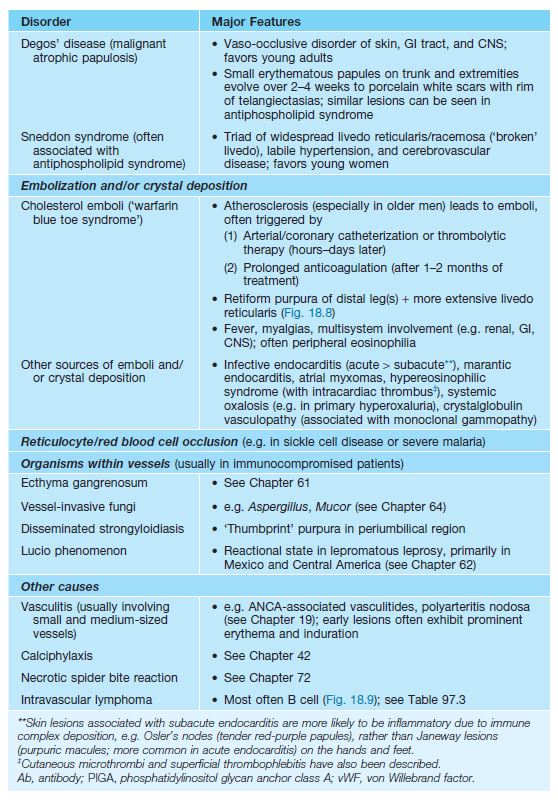

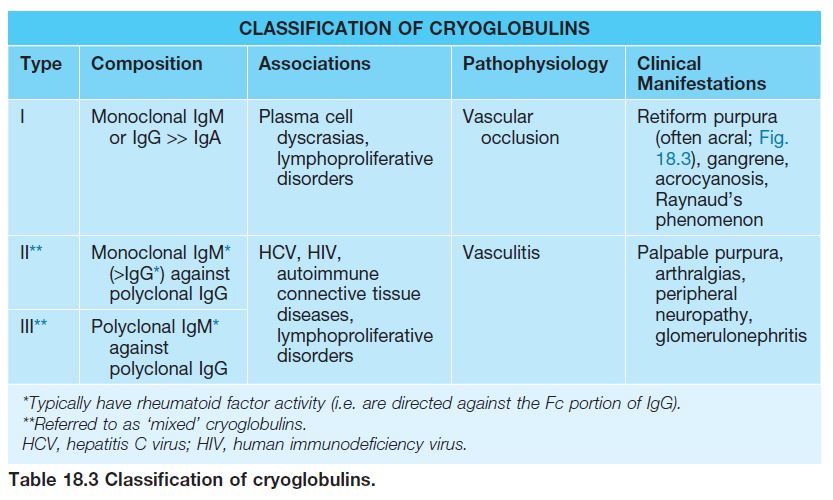

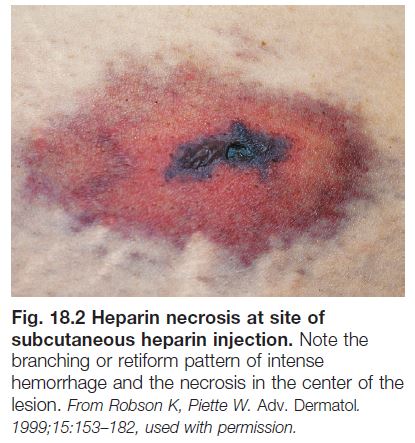

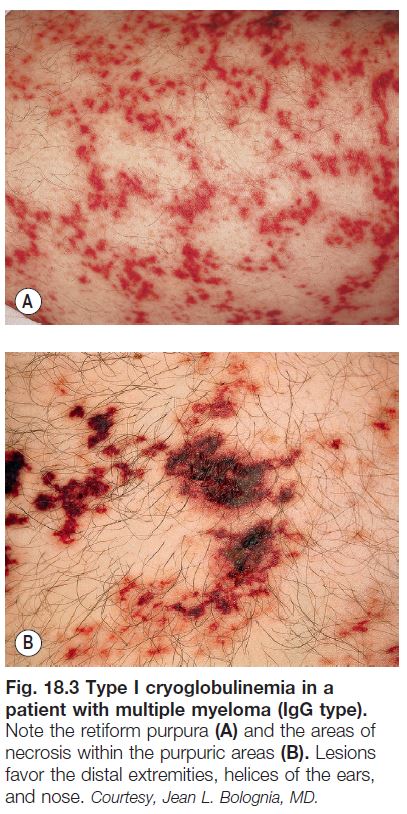

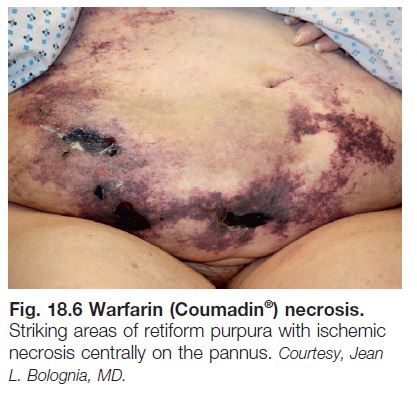

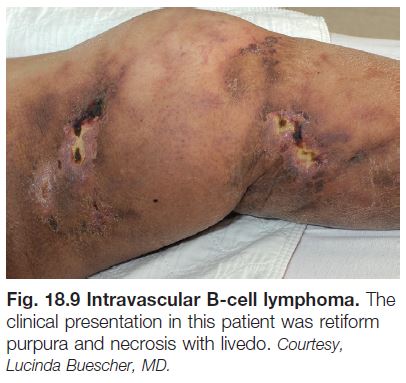

– Retiform purpura: reticulated, branching or stellate morphology, which reflects occlusion of the vessels that produce the livedo reticularis pattern (see Chapter 87; Tables 18.2 and 18.3; Figs. 18.1C and 18.2–18.9).

– Classic ‘palpable purpura’: round redpurple papules that are occasionally targetoid, with a component of blanching erythema in early lesions; represents the most common presentation of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis (see

Chapter 19; Fig. 18.1D).

• A biopsy specimen can be helpful in determining the etiology of a purpuric eruption, e.g. whether there is vascular occlusion with minimal inflammation or vasculitis (inflammation and fibrinoid necrosis of vessel

walls); because secondary changes of vasculitis may be seen when an older lesion of microvascular occlusion is sampled, and likewise a late lesion of vasculitis may have minimal residual inflammation, it is preferable to

choose a well-developed but relatively early lesion (e.g. 24–48 hours old).

Selected Microvascular Occlusion Syndromes (See Table 18.2)

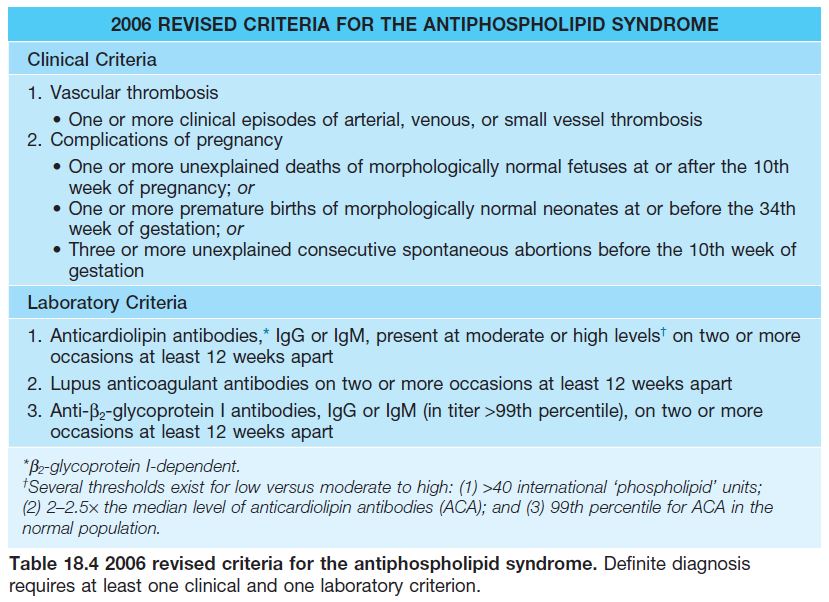

Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APLS)

• Acquired systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by vascular thrombosis and/or pregnancy complications in the presence of elevated levels of antiphospholipid antibodies (Table 18.4).

• Predilection for young to middle-aged women (5 : 1 female : male ratio in adults) and often associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.

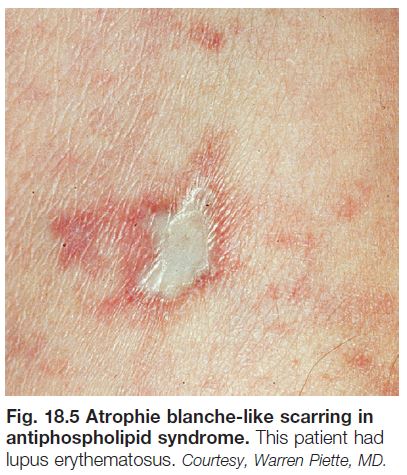

• Cutaneous findings can include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura progressing to cutaneous necrosis, leg ulcers, livedoid vasculopathy, Degos-like lesions, nail bed infarcts, superficial thrombophlebitis and anetoderma (see Figs. 18.4 and 18.5).

• Deep venous thrombosis and CNS disease are the most common extracutaneous manifestations; catastrophic APLS affecting multiple organ systems together with widespread retiform purpura occasionally occurs.

• Rx: anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents; also immunomodulatory agents (e.g. systemic CS, rituximab) for catastrophic APLS.

Livedoid Vasculopathy

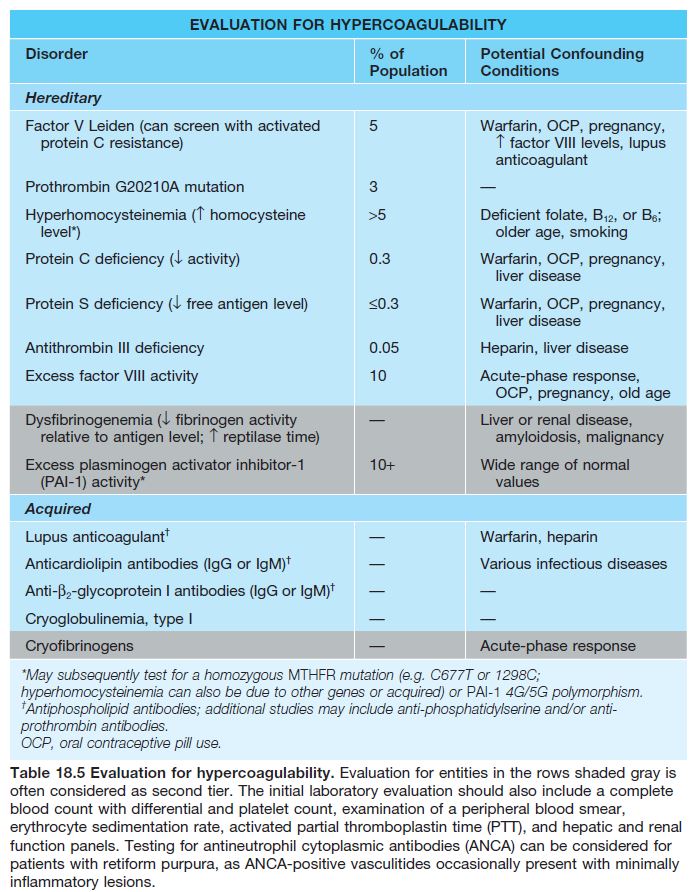

• Chronic condition that occurs primarily in young to middle-aged women, often with an underlying hypercoagulable state (Table 18.5).

• Recurrent development of hemorrhagic crusts resembling ground pepper and extremely painful, punched-out ulcers on the legs (especially the ankles); frequently arises within a background of retiform purpura ± livedo reticularis (see Fig. 18.7).

• The ulcers heal slowly, forming stellate, ivory-white, atrophic scars bordered by papular telangiectasias and hemosiderin pigmentation; such lesions, referred to as atrophie blanche, also occur in other settings

such as venous hypertension, antiphospholipid syndrome (see Fig. 18.5), and cutaneous vasculitis.

• Rx: anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and fibrinolytic agents (especially if hypercoagulability).

Other Purpuric Disorders

Pigmented Purpuric Dermatoses (Capillaritis)

• Group of disorders characterized by clustered petechial hemorrhage due to inflammation affecting capillaries.

• Schamberg’s disease: most common form, occurring in both children and adults; recurrent crops of discrete yellow-brown patches containing pinpoint petechiae (‘cayenne pepper’) on the lower legs > thighs, buttocks,

trunk, and arms (Fig. 18.10A); the yellowbrown color reflects deposits of hemosiderin, derived from extravasated RBCs, within the dermis.

• Purpura annularis telangiectodes (of Majocchi): favors adolescent girls and young women; expanding annular plaques with punctate telangiectasias and petechiae in their borders (Fig. 18.11).

• Lichen aureus: solitary golden to rustcolored or purple-brown patch or thin plaque, typically on the leg overlying a perforator vein.

• Other forms include pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis presenting as red-brown papules and eczematid-like purpura with scaling and pruritus; these variants favor the lower legs of men.

• DDx: ‘stasis purpura’ presenting as petechiae superimposed on diffuse hemosiderin deposition on the legs (see Fig. 18.10B); purpuric forms of allergic contact dermatitis, drug eruptions or mycosis fungoides; suctioninduced

purpura (e.g. with cupping), hypergammaglobulinemic purpura of Waldenström, angioma serpiginosum; for lichenoid variant: primarily small vessel vasculitis.

• Rx: difficult; topical CS if pruritic, phototherapy.

Hypergammaglobulinemic Purpura of Waldenström

• Recurrent crops of petechiae, purpuric macules, and/or palpable purpura (Fig. 18.12) on the lower extremities, often in young women with an autoimmune connective tissue disease (especially Sjögren’s syndrome).

• Associated with polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, an elevated ESR, rheumatoid factor (IgG or IgA), and anti-Ro/La (SS-A/B) antibodies.