Eczema (eczematous inflammation) is the most common inflammatory skin disease. Although the term dermatitis is often used to refer to an eczematous eruption, the word means inflammation of the skin and is not synonymous with eczematous processes. Recognizing a rash as eczematous rather than psoriasiform or lichenoid, for example, is of fundamental importance if one is to effectively diagnose skin disease. Here, as with other skin diseases, it is important to look carefully at the rash and to determine the primary lesion.

It is essential to recognize the quality and characteristics of the components of eczematous inflammation (erythema, scale, and vesicles) and to determine how these differ from other rashes with similar features. Once familiar with these features, the experienced clinician can recognize a process as eczematous even in the presence of secondary changes produced by scratching, infection, or irritation. With the diagnosis of eczematous inflammation established, a major part of the diagnostic puzzle has been solved.

STAGES OF ECZEMATOUS INFLAMMATION

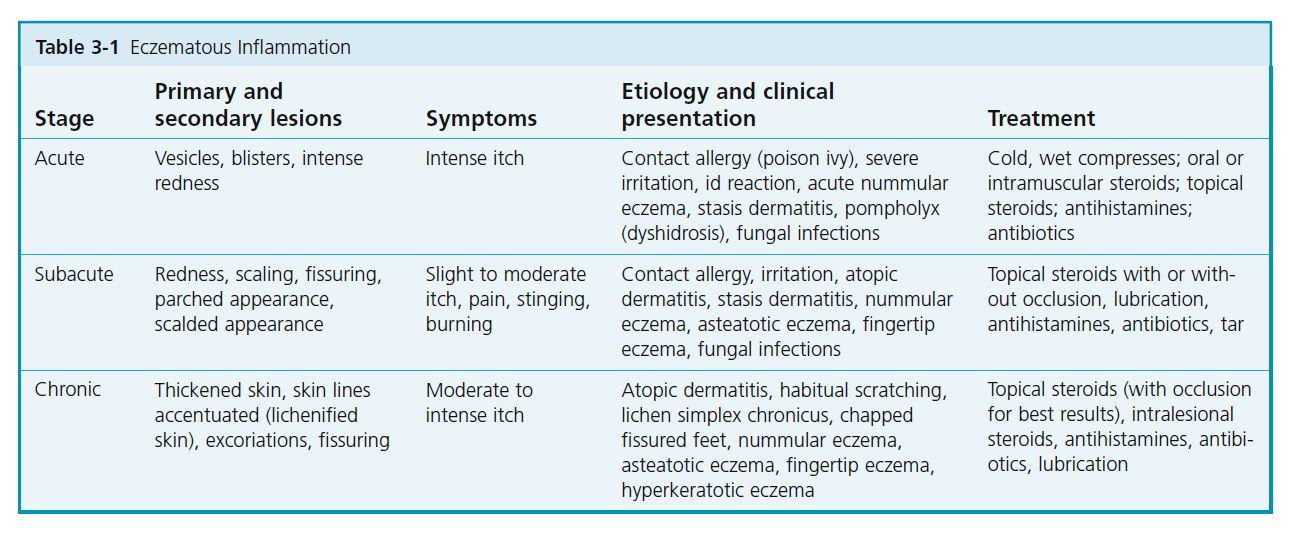

There are three stages of eczema: acute, subacute, and chronic . Each represents a stage in the evolution of a dynamic inflammatory process ( Table 3-1 ). Clinically, an eczematous disease may start at any stage and evolve into another. Most eczematous diseases, if left alone (i.e., neither irritated, scratched, nor medicated), resolve in time without complication. This ideal situation is almost never realized; scratching, irritation, or attempts at topical treatment are almost inevitable. Some degree of itching is a cardinal feature of eczematous inflammation.

Acute eczematous inflammation

ETIOLOGY. Inflammation is caused by contact with specific allergens such as Rhus (poison ivy, oak, or sumac) and chemicals. In the id reaction, vesicular reactions occur at a distant site during or after a fungal infection, stasis dermatitis, or other acute inflammatory processes.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS. The degree of inflammation varies from moderate to intense. A bright red, swollen plaque with a pebbly surface evolves in hours. Close examination of the surface reveals tiny, clear, serum-filled vesicles ( Figures 3-1 to 3-3 ). The eruption may not progress or it may evolve to develop blisters. The vesicles and blisters may be confluent and are often linear. Linear lesions result from dragging the offending agent across the skin with the finger during scratching. The degree of inflammation in cases caused by allergy is directly proportional to the quantity of antigen deposited on the skin. Excoriation predisposes to infection and causes serum, crust, and purulent material to accumulate.

COURSE. Lesions may begin to appear from hours to 2 to 3 days after exposure and may continue to appear for 1 week or more. These later occurring, less inflammatory lesions are confusing to the patient, who cannot recall additional exposure. Lesions produced by small amounts of allergen are slower to evolve. They are not produced, as is generally believed, by contact with the serum of ruptured blisters, because the blister fl uid does not contain the offending chemical. Acute eczematous inflammation evolves into a subacute stage before resolving.

TREATMENT

Cool, wet dressings. The evaporative cooling produced by wet compresses causes vasoconstriction and rapidly suppresses inflammation and itching. Burow’s powder, available in a 12-packet box, may be added to the solution to suppress bacterial growth, but water alone is usually sufficient. A clean cotton cloth is soaked in cool water, folded several times, and placed directly over the affected areas. Evaporative cooling produces vasoconstriction and decreases serum production. Wet compresses should not be held in place and covered with towels or plastic wrap because this prevents evaporation. The wet cloth macerates vesicles and, when removed, mechanically debrides the area and prevents serum and crust from accumulating. Wet compresses should be removed after 30 minutes and replaced with a freshly soaked cloth. It is tempting to leave the drying compress in place and to wet it again by pouring solution onto the cloth. Although evaporative cooling will continue, irritation may occur from the accumulation of scale, crust, and serum and from the increased concentration of aluminum sulfate and calcium acetate, the active ingredients in Burow’s powder.

Oral corticosteroids. Oral corticosteroids such as prednisone are useful for controlling intense or widespread inflammation and may be used in addition to wet dressings. Prednisone controls most cases of poison ivy when it is taken in 20-mg doses twice a day for 7 to 14 days (for adults); however, to treat intense or generalized inflammation, prednisone may be started at 30 mg or more twice a day and maintained at that level for 3 to 5 days. Sometimes 21 days of treatment are required for adequate control. The dosage should not be tapered for these relatively short courses because lower dosages may not give the desired antiinflammatory effect. Inflammation may reappear as diffuse erythema and may even be more extensive if the dosage is too low or is tapered too rapidly. Commercially available steroid dose packs taper the dosage and provide treatment for too short a time and so should not be used. Topical corticosteroids are of little use in the acute stage because the cream does not penetrate through the vesicles.

Antihistamines. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and hydroxyzine (Atarax), do not alter the course of the disease, but they relieve itching and provide enough sedation so patients can sleep. They are given every 4 hours as needed.

Antibiotics. The use of oral antibiotics may greatly hasten resolution of the disease if signs of superficial secondary infection, such as pustules, purulent material, and crusts, are present. Staphylococcus is the usual pathogen, and cultures are not routinely necessary. Deep infection (cellulitis) is rare with acute eczema. Cephalexin and dicloxacillin are effective; topical antibiotics are much less effective.

Subacute eczematous inflammation

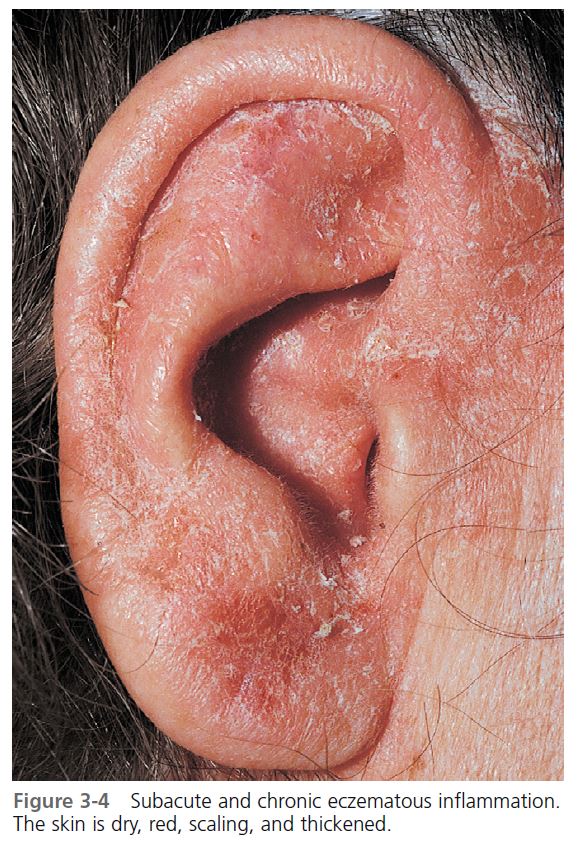

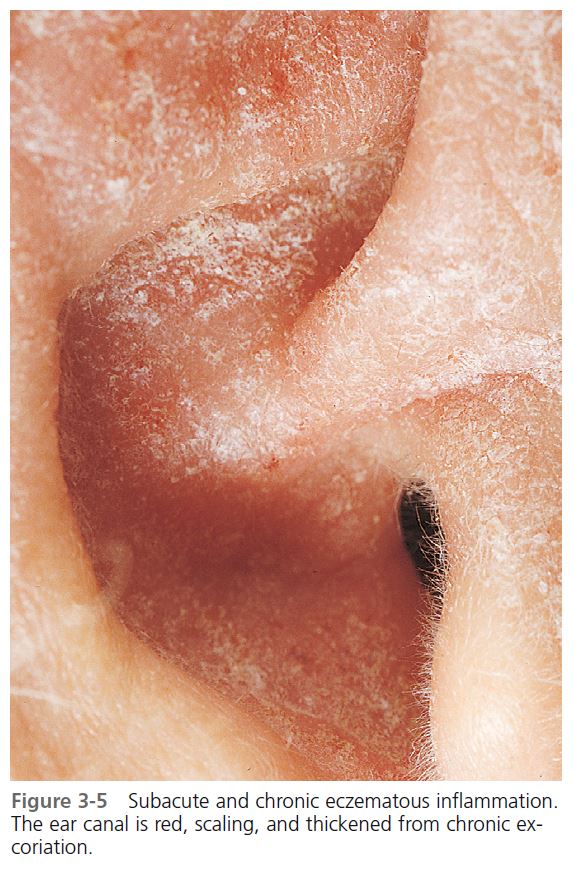

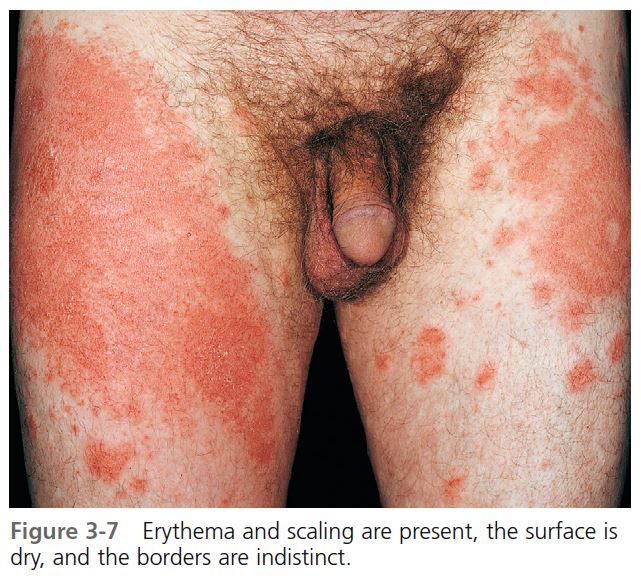

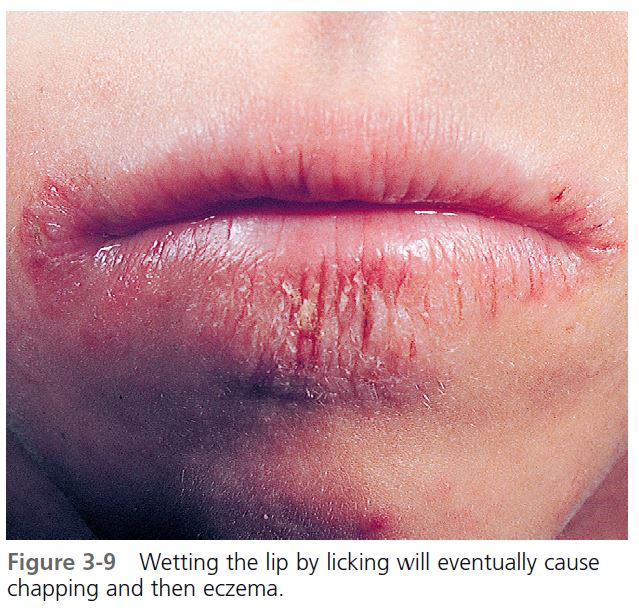

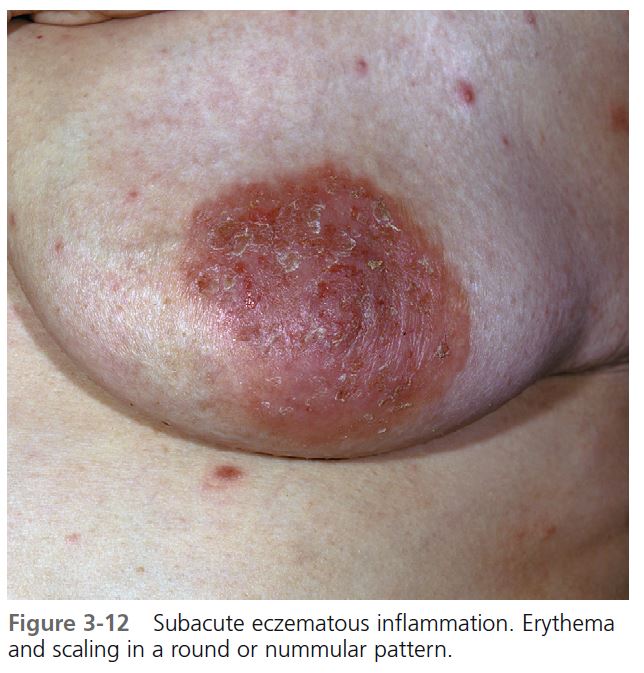

PHYSICAL FINDINGS. Erythema and scale are present in various patterns, usually with indistinct borders ( Figures 3-4 and 3-5 ). The redness may be faint or intense ( Figures 3-6 through 3-9 ). Psoriasis, superficial fungal infections, and eczematous inflammation may have a similar appearance ( Figures 3-10 through 3-12 ). The borders of the plaques of psoriasis and superficial fungal infections are well-defined. Psoriatic plaques have a deep, rich red color and silvery white scales.

SYMPTOMS. These vary from no itching to intense itching.

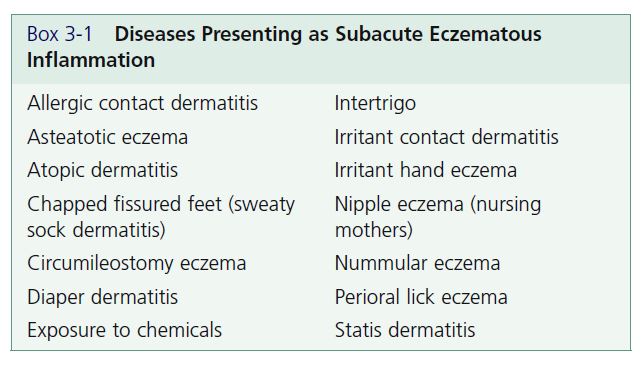

COURSE. Subacute eczematous inflammation may be the initial stage or it may follow acute inflammation. Irritation, allergy, or infection can convert a subacute process into an acute process. Subacute inflammation resolves spontaneously without scarring if all sources of irritation and allergy are withdrawn. Excess drying created from washing or continued use of wet dressings causes cracking and fissures. If excoriation is not controlled, the subacute process can be converted to a chronic process. Diseases that have subacute eczematous inflammation as a characteristic are listed in Box 3-1 .

TREATMENT. It is important to discontinue wet dressings when acute inflammation evolves into subacute inflammation. Excess drying creates cracking and fi ssures, which predispose to infection.

Topical corticosteroids. These agents are the treatment of choice (see Chapter 2 ). Creams may be applied two to four times a day or with occlusion. Ointments may be applied two to four times a day for drier lesions. Subacute inflammation requires group III through V corticosteroids for rapid control. Occlusion with creams hastens resolution, and less expensive, weaker products such as triamcinolone cream 0.1% (Kenalog) give excellent results. Staphylococcus aureus colonizes eczematous lesions, but studies show their numbers are signifi cantly reduced following treatment with topical steroids.

Topical macrolide immune suppressants. Tacrolimus ointment (Protopic) and pimecrolimus cream (Elidel) are the first topical macrolide immune suppressants that are not hydrocortisone derivatives. They inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines in T cells and mast cells and prevent the release of preformed inflammatory mediators from mast cells. Dermal atrophy does not occur. These agents are effective for the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases, such as atopic dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis, and irritant contact dermatitis. They are approved for use in children 2 years or older. Response to these agents is slower than the response to topical steroids. Topical steroids may be used for several days before the use of these agents to obtain rapid control.

Pimecrolimus (Elidel) cream. Pimecrolimus permeates through skin at a lower rate than tacrolimus, indicating a lower potential for percutaneous absorption. The cream is applied twice a day and may be used on the face. Continuous long-term use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in any age group should be avoided, and application limited to areas of involvement with dermatitis.

Tacrolimus ointment (Protopic). Tacrolimus is effective in the treatment of children (aged 2 years and older) and adults with atopic dermatitis and eczema. The most prominent adverse event is application site burning and erythema. It is available in 0.03% and 0.1% ointment formulations. Some clinicians find the 0.03% concentration to be marginally effective. Continuous long-term use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in any age group should be avoided, and application limited to areas of involvement with dermatitis.

Doxepin cream. A topical form of the antidepressant doxepin (doxepin 5% cream; Zonalon) is effective for the relief of pruritus associated with eczema in adults and children aged over 12 years. The two most common adverse effects are stinging at the site of application and drowsiness. The medication can be applied four times a day as needed.

Lubrication. This is a simple but essential part of therapy. Inflamed skin becomes dry and is more susceptible to further irritation and infl ammation. Resolved dry areas may easily relapse into subacute eczema if proper lubrication is neglected. Lubricants are best applied a few hours after topical steroids and should be continued for days or weeks after the infl ammation has cleared. Frequent application (one to four times a day) should be encouraged. Applying lubricants directly after the skin has been patted dry following a shower seals in moisture. Lotions or creams with or without the hydrating chemicals urea and lactic acid may be used. Bath oils are very useful if used in amounts sufficient to make the skin feel oily when the patient leaves the tub.

Lotions. Curél, DML, Lubriderm, Cetaphil, or any of the other lotions listed in the Formulary are useful.

Creams. DML, Moisturel, Neutrogena, Nivea, Eucerin, and Acid Mantle or any of the other creams listed in the Formulary are useful.

Mild soaps. Frequent washing with a drying soap, such as Ivory, delays healing. Infrequent washing with mild or superfatted soaps (e.g., Dove, Cetaphil, Basis—see the Formulary) should be encouraged. It is usually not necessary to use hypoallergenic soaps or to avoid perfumed soaps. Although allergy to perfumes occurs, the incidence is low.

Antibiotics. Eczematous plaques that remain bright red during treatment with topical steroids may be infected. Infected subacute eczema should be treated with appropriate systemic antibiotics, which are usually those active against Staphylococci. Systemic antibiotics are more effective than topical antibiotics or antibiotic-steroid combination creams.

Tar. Tar ointments, baths, and soaps were among the few effective therapeutic agents available for the treatment of eczema before the introduction of topical steroids. Topical steroids provide rapid and lasting control of eczema in most cases. Some forms of eczema, such as atopic dermatitis and irritant eczema, tend to recur. Topical steroids become less effective with long-term use. Tar is sometimes an effective alternative in this setting. Tar ointments or creams may be used for long-term control or between short courses of topical steroids.

ADULT-ONSET RECALCITRANT ECZEMA AND MALIGNANCY

Generalized eczema or erythroderma may be the presenting sign of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Intractable pruritus has been associated with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Unexplained eczema of adult onset may be associated with an underlying lymphoproliferative malignancy. Patients may have widespread erythematous plaques that are poorly responsive to therapy. When a readily identifiable cause (e.g., contactants, drugs, or atopy) is not found, a systematic evaluation should be pursued.

Chronic eczematous inflammation

ETIOLOGY. Chronic eczematous inflammation may be caused by irritation of subacute inflammation, or it may appear as lichen simplex chronicus.

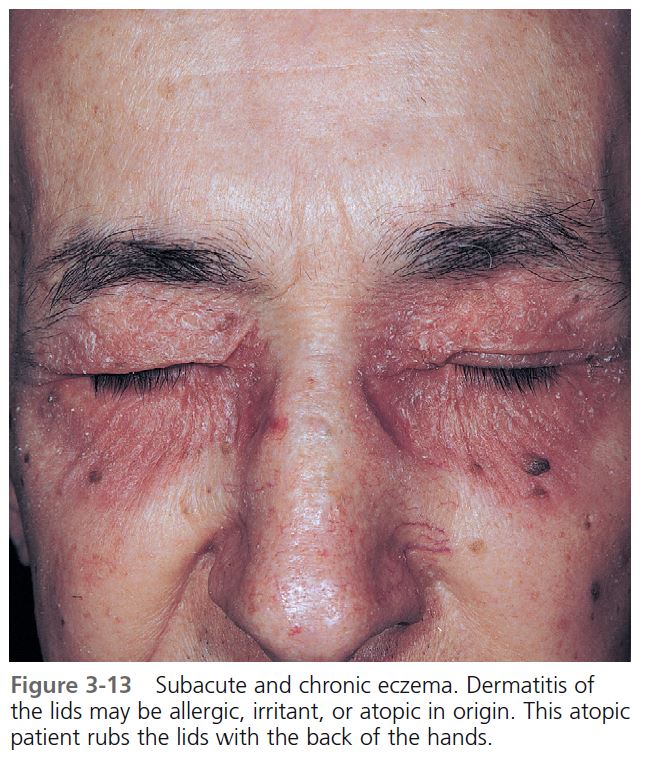

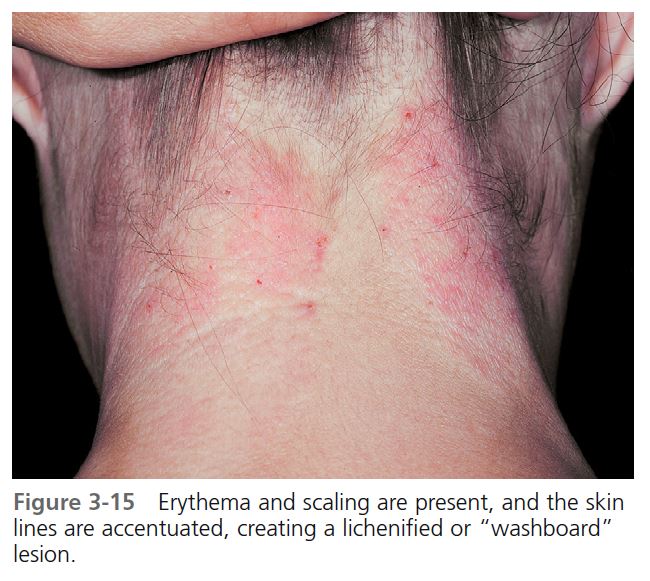

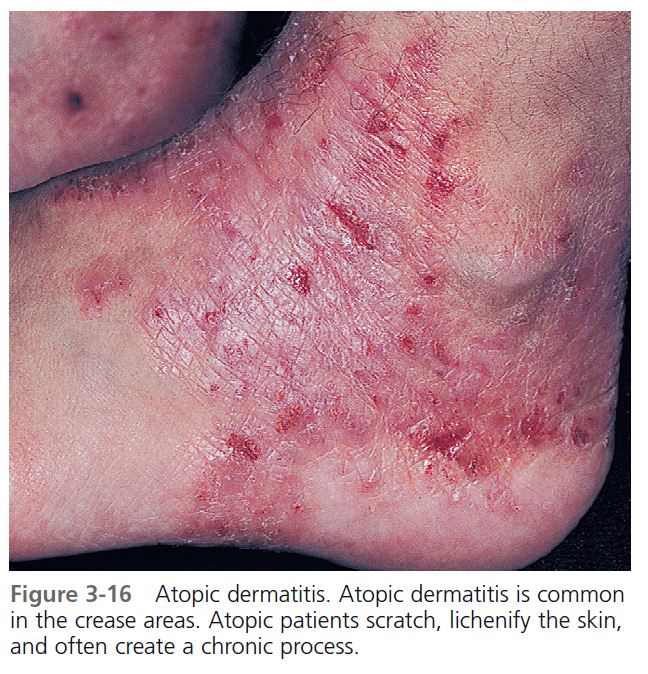

PHYSICAL FINDINGS. Chronic eczematous inflammation is a clinical-pathologic entity and does not indicate simply any long-lasting stage of eczema. If scratching is not controlled, subacute eczematous inflammation can be modified and converted to chronic eczematous inflammation ( Figure 3-13 ). The inflamed area thickens, and surface skin markings may become more prominent. Thick plaques with deep parallel skin marking (“washboard” lesion) are said to be lichenified ( Figure 3-14 ). The border is well defined but not as sharply defined as it is in psoriasis ( Figure 3-15 ). The sites most commonly involved are those areas that are easily reached and associated with habitual scratching (e.g., dorsal feet, lateral forearms, anus, and occipital scalp), areas where eczema tends to be long-lasting (e.g., the lower legs, as in stasis dermatitis), and the crease areas (antecubital and popliteal fossa, wrists, behind the ears, and ankles) in atopic dermatitis ( Figures 3-16 to 3-18 ).

SYMPTOMS. There is moderate to intense itching. Scratching sometimes becomes violent, leading to excoriation and digging, and ceases only when pain has replaced the itch. Patients with chronic inflammation scratch while asleep.

COURSE. Scratching and rubbing become habitual and are often done unconsciously. The disease then becomes self-perpetuating. Scratching leads to thickening of the skin, which itches more than before. It is this habitual manipulation that causes the difficulty in eradicating this disease. Some patients enjoy the feeling of relief that comes from scratching and may actually desire the reappearance of their disease after treatment.

TREATMENT. Chronic eczematous inflammation is resistant to treatment and requires potent steroid therapy.

Topical steroids. Groups II through V topical steroids are used with occlusion each night until the inflammation clears—usually in 1 to 3 weeks; group I topical steroids are used without occlusion. Topical steroid foams (e.g., clobetasol foam) may be very effective. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% can be used as a primary treatment or used alternately with topical steroids.

Intralesional injection. Intralesional injection (Kenalog, 10 mg/ml) is a very effective mode of therapy. Lesions that have been present for years may completely resolve after one injection or a short series of injections. The medicine is delivered with a 27- or 30-gauge needle, and the entire plaque is infiltrated until it blanches white. Resistant plaques require additional injections given at 3- to 4-week intervals.

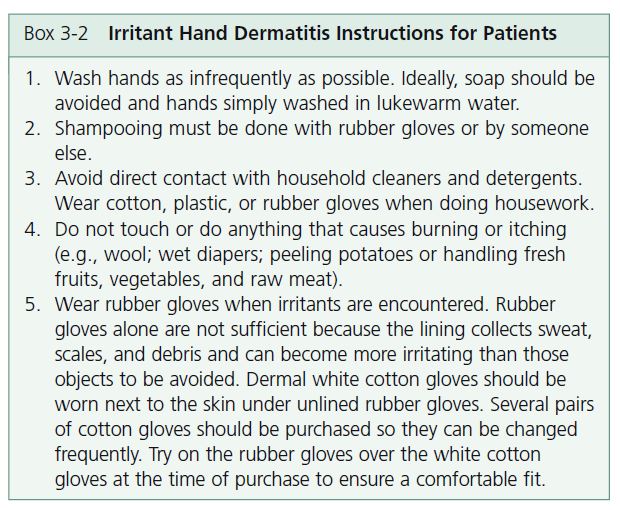

Inflammation of the hands is one of the most common problems encountered by the dermatologist. Hand dermatitis causes discomfort and embarrassment and, because of its location, interferes significantly with normal daily activities. Hand dermatitis is common in industrial occupations: it can threaten job security if inflammation cannot be controlled. Box 3-2 lists instructions for patients with irritant hand dermatitis.

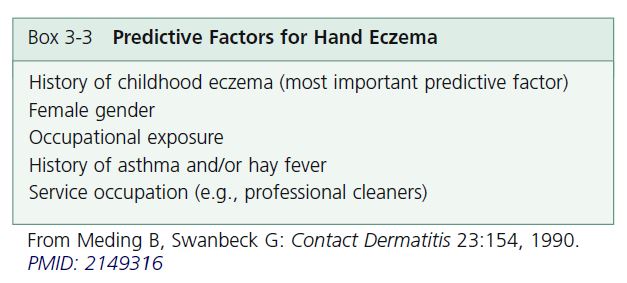

EPIDEMIOLOGY. A large study provided the following statistics: the prevalence of hand eczema was approximately 5.4% and was twice as common in females as in males. The most common type of hand eczema was irritant contact dermatitis (35%), followed by atopic hand eczema (22%) and allergic contact dermatitis (19%). The most common contact allergies were to nickel, cobalt, fragrance mix, balsam of Peru, and colophony. Of all the occupations studied, cleaners had the highest prevalence at 21.3%. Hand eczema was more common among people reporting occupational exposure. The most harmful exposure was to chemicals, water and detergents, dust, and dry dirt. A change of occupation was reported by 8% and was most common in service workers. Hairdressers had the highest frequency of change. Hand eczema was shown to be a long-lasting disease with a relapsing course; 69% of the patients had consulted a physician, and 21% had been on sick leave at least once because of hand eczema. The mean total sick-leave time was 18.9 weeks; the median was 8 weeks. PMID: 2145721 The most important predictive factors for hand eczema are listed in Box 3-3.

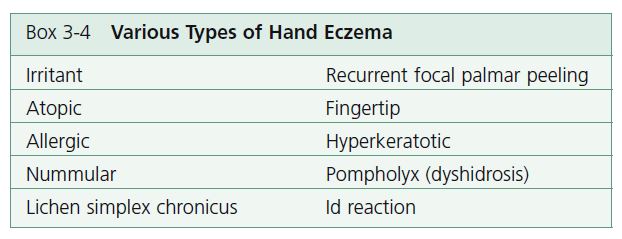

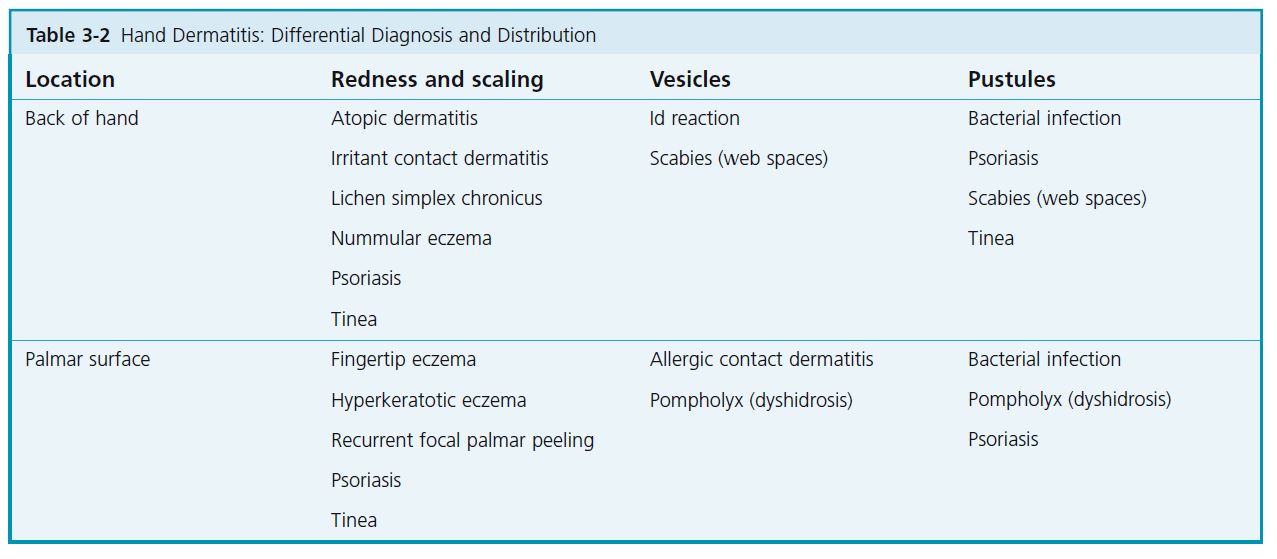

DIAGNOSIS. The diagnosis and management of hand eczema are a challenge. There is almost no association between clinical pattern and etiology. No distribution of eczema is typically allergic, irritant, or endogenous. Not only are there many patterns of eczematous inflammation ( Table 3-2 ), but also there are other diseases, such as psoriasis, that may appear eczematous. Many patients diagnosed with hand eczema actually have psoriasis. The original primary lesions and their distribution become modified with time by irritants, excoriation, infection, and treatment. All stages of eczematous infl ammation may be encountered in hand eczema ( Box 3-4 ).

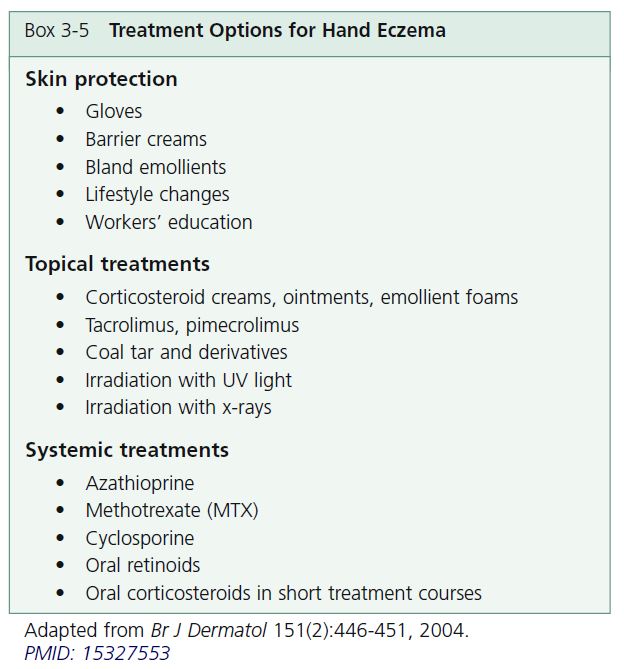

TREATMENT. Most patients can be managed with skin protection and topical treatments. Skin protection and emollients are important. Topical treatments control the disease but require long-term intermittent use. Systemic treatments provide temporary remission but long-term use of potentially toxic drugs is discouraged. Treatment options are outlined in Box 3-5 .

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS. Hand eczema often has a long-lasting and relapsing course. Patients with ongoing hand eczema experience negative psychosocial consequences. There may be far-reaching consequences including long sick-leave periods, sick pension, and changes of occupation.

Irritant contact dermatitis

Irritant hand dermatitis (housewives’ eczema, dishpan hands, detergent hands) is the most common type of hand inflammation. Some people can withstand long periods of repeated exposure to various chemicals and maintain normal skin. At the other end of the spectrum, there are those who develop chapping and eczema from simple hand washing. Patients whose hands are easily irritated may have an atopic diathesis.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY. The stratum corneum is the protective envelope that prevents exogenous material from entering the skin and prevents body water from escaping. The stratum corneum is composed of dead cells, lipids (from sebum and cellular debris), and water-binding organic chemicals. The stratum corneum of the palms is thicker than that of the backs of the hands and is more resistant to irritation. The pH of this surface layer is slightly acidic. Environmental factors or elements that change any component of the stratum corneum interfere with its protective function and expose the skin to irritants. Factors such as cold winter air and low humidity promote water loss. Substances such as organic solvents and alkaline soaps extract water-binding chemicals and lipids. Once enough of these protective elements have been extracted, the skin decompensates and becomes eczematous.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION. The degree of inflammation depends on factors such as strength and concentration of the chemical, individual susceptibility, site of contact, and time of year. Allergy, infection, scratching, and stress modify the picture.

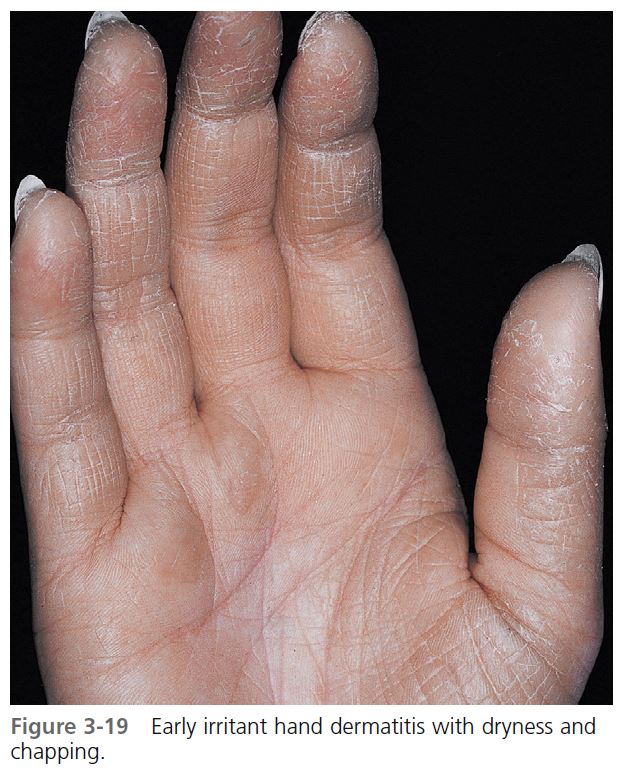

STAGES OF INFLAMMATION. Dryness and chapping are the initial changes ( Figure 3-19 ). Very painful cracks and fissures occur, particularly in joint crease areas and around the fi ngertips. The backs of the hands become red, swollen, and tender. The palmar surface, especially that of the fingers, becomes red and continues to be dry and cracked. A red, smooth, shiny, delicate surface that splits easily with the slightest trauma may develop. These are subacute eczematous changes ( Figure 3-20 ). Acute eczematous inflammation occurs with further irritation creating vesicles that ooze and crust. Itching intensifies, and excoriation leads to infection ( Figures 3-21 and 3-22 ). Necrosis and ulceration followed by scarring occur if the irritating chemical is too caustic.

PATIENTS AT RISK. Individuals at risk include mothers with young children (e.g., from changing diapers), individuals whose jobs require repeated wetting and drying (e.g., surgeons, dentists, dishwashers, bartenders, fi shermen), industrial workers whose jobs require contact with chemicals (e.g., cutting oils), and patients with the atopic diathesis.

PREVENTION. One study revealed that hospital staff members who used an emulsion cleanser (e.g., Cetaphil lotion, Duosoft [in Europe]) had signifi cantly less dryness and eczema than those who used a liquid soap. Regular use of emollients prevented irritant dermatitis caused by a detergent.

BARRIER-PROTECTANT CREAMS. Loss of skin barrier function by mechanical or chemical insults may result in water loss and hand eczema. Barrier creams (see Box 3-6 ) applied at least twice a day on all exposed areas protect the skin and are formulated to be either water-repellent or oil repellent. The water-repellent types offer little protection against oils or solvents.

TREATMENT. The inflammation is treated as outlined under “Stages of eczematous infl ammation.” Lubrication and avoidance of further irritation help to prevent recurrence. A program of irritant avoidance should be carefully outlined for each patient (see Box 3-2 ).

Atopic hand dermatitis

Hand dermatitis may be the most common form of adult atopic dermatitis (see Chapter 5 ). Hand eczema is significantly more common in people with a history of atopic dermatitis than in others. The following factors predict the occurrence of hand eczema in adults with a history of atopic dermatitis:

• Hand dermatitis before age 15

• Persistent eczema on the body

• Dry or itchy skin in adult life

• Widespread atopic dermatitis in childhood

Many people with atopic dermatitis develop hand eczema independently of exposure to irritants, but such exposure causes additional irritant contact dermatitis.

The backs of the hands, particularly the fingers, are affected ( Figure 3-23 ). The dermatitis begins as a typical irritant reaction with chapping and erythema. Several forms of eczematous dermatitis evolve; erythema, edema, vesiculation, crusting, excoriation, scaling, and lichenification appear and are intensifi ed by scratching. Management for atopic hand eczema is the same as that for irritant hand eczema.

Allergic contact dermatitis

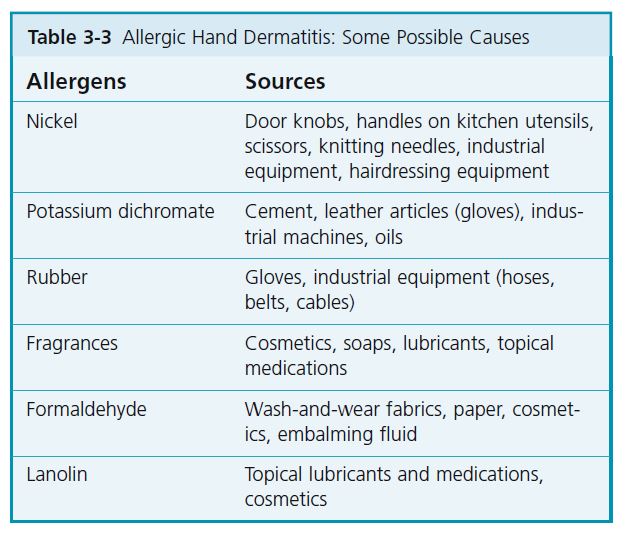

Allergic contact dermatitis of the hands is not as common as irritant dermatitis. However, allergy as a possible cause of hand eczema, no matter what the pattern, should always be considered in the differential diagnosis; it may be investigated by patch testing in appropriate cases. The incidence of allergy in hand eczema was demonstrated by patch testing in a study of 220 patients with hand eczema. In 12% of the 220 patients, the diagnosis was established with the aid of a standard screening series now available in a modified form (T.R.U.E. TEST). Another 5% of the cases were diagnosed as a result of testing with additional allergens. The hand eczema in these two groups (17%) changed dramatically after identification and avoidance of the allergens found by patch testing. Table 3-3 lists some possible causes of allergic hand dermatitis.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS. The diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis is obvious when the area of infl ammation corresponds exactly to the area covered by the allergen (e.g., a round patch of eczema under a watch or inflammation in the shape of a sandal strap on the foot). Similar clues may be present with hand eczema, but in many cases allergic and irritant hand eczemas cannot be distinguished by their clinical presentation. Hand inflammation, whatever the source, is increased by further exposure to irritating chemicals, washing, scratching, medication, and infection. Inflammation of the dorsum of the hand is more often irritant or atopic than allergic.

TREATMENT. Allergy may initially appear as acute, subacute, or chronic eczematous inflammation and is managed accordingly.

Nummular eczema

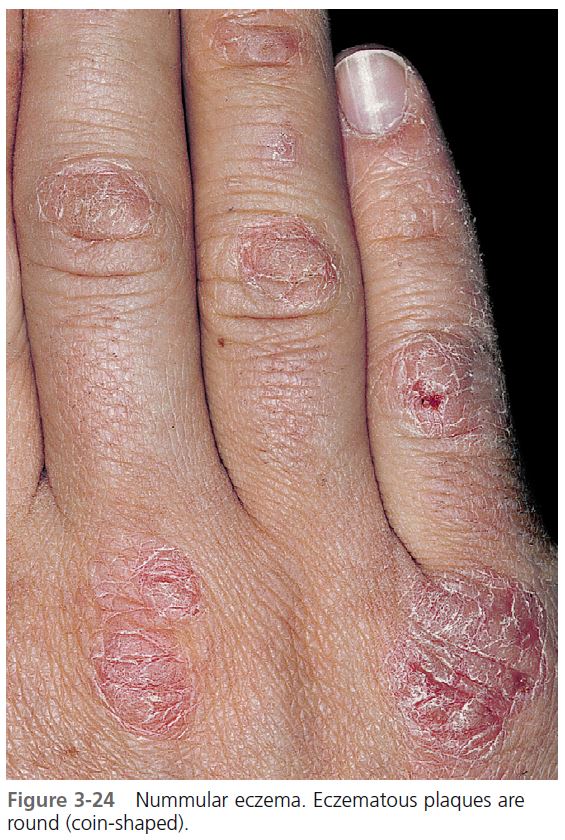

Eczema that appears as one or several coin-shaped plaques is called nummular eczema . This pattern often occurs on the extremities but may also present as hand eczema. The plaques are usually confined to the backs of the hands ( Figure 3-24 ). The number of lesions may increase, but once they are established they tend to remain the same size. The inflammation is either subacute or chronic and itching is moderate to intense. The cause is unknown. Thick, chronic, scaling plaques of nummular eczema look like psoriasis; treatment for nummular eczema is the same as that for subacute or chronic eczema.

Lichen simplex chronicus

A localized plaque of chronic eczematous inflammation that is created by habitual scratching is called lichen simplex chronicus or localized neurodermatitis . The back of the wrist is a typical site. The plaque is thick with prominent skin lines (lichenification) and the margins are fairly sharp. Once established, the plaque does not usually increase in area. Lichen simplex chronicus is treated in the same manner as chronic eczematous inflammation.

Recurrent focal palmar peeling

Keratolysis exfoliativa or recurrent focal palmar peeling is a common, chronic, asymptomatic, noninflammatory, bilateral peeling of the palms of the hands and occasionally soles of the feet; its cause is unknown ( Figure 3-25 ). The eruption is most common during the summer months and is often associated with sweaty palms and soles. Some people experience this phenomenon only once, whereas others have repeated episodes. Scaling starts simultaneously from several points on the palms or soles with 2 or 3 mm of round scales that appear to have originated from a ruptured vesicle; however, these vesicles are never seen. The scaling continues to peel and extend peripherally, forming larger, roughly circular areas that resemble ringworm whereas the central area becomes slightly red and tender. The scaling borders may coalesce. The condition resolves in 1 to 3 weeks and requires no therapy other than lubrication.

Hyperkeratotic eczema

A very thick, chronic form of eczema that occurs on the palms and occasionally the soles is seen almost exclusively in men. One or several plaques of yellow-brown, dense scale increase in thickness and form deep interconnecting cracks over the surface, similar to mud drying in a river bed ( Figure 3-26 ). The dense scale, unlike callus, is moist below the surface and is not easily pared with a blade. Patients discover that the scale is firmly adherent to the epidermis when they attempt to peel off the thick scale, and this exposes tender bleeding areas of the dermis. Hyperkeratotic eczema may result from allergy or excoriation and irritation, but in most cases the cause is not apparent. The disease is chronic and may last for years. Psoriasis and lichen simplex chronicus must be considered in the differential diagnosis. The disease is treated like chronic eczema; although the plaques respond to group II steroid cream and occlusion, recurrences are frequent. Patch testing is indicated for recurrent disease.

Fingertip eczema

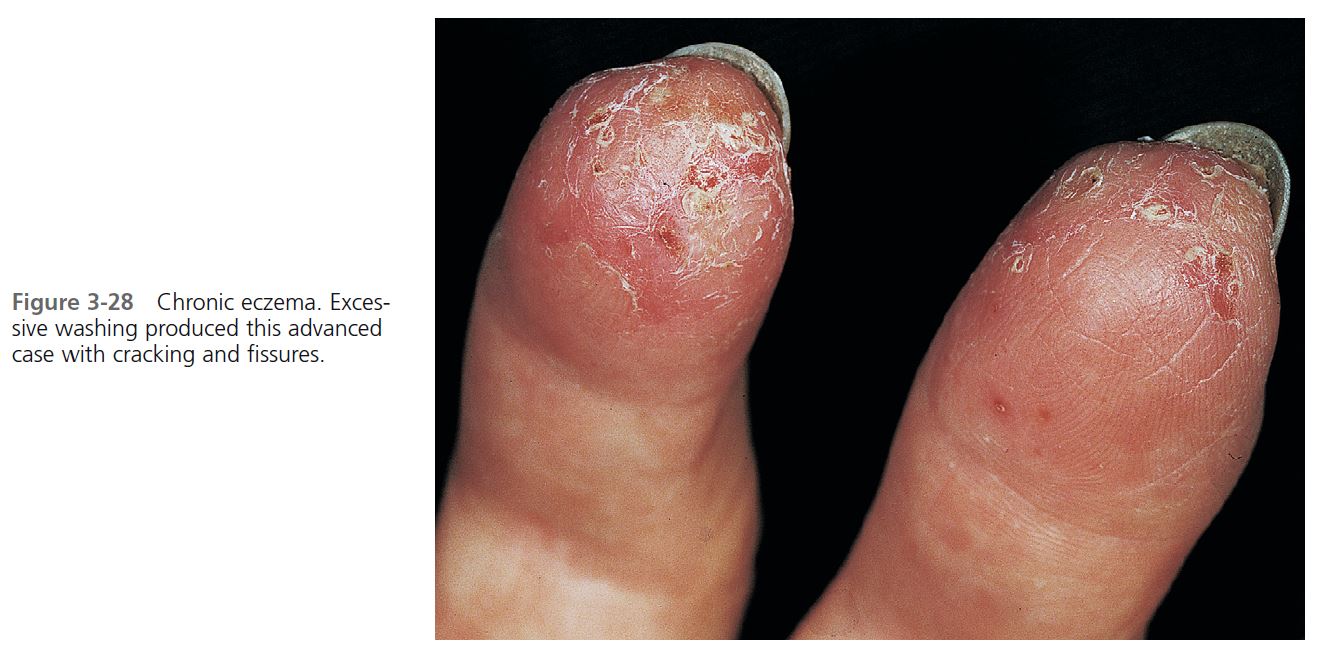

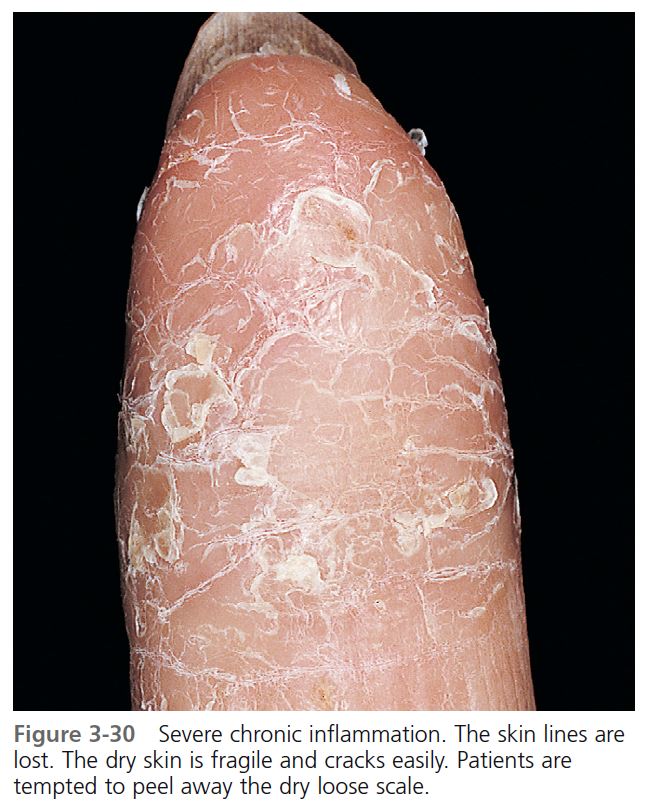

A very dry, chronic form of eczema of the palmar surface of the fingertips may be the result of an allergic reaction (e.g., to plant bulbs or resins) or may occur in children and adults as an isolated phenomenon of unknown cause. One finger or several fingers may be involved. Initially the skin may be moist and then may become dry, cracked, and scaly ( Figure 3-27 ). The skin peels from the fingertips distally, exposing a very dry, red, cracked, fissured, tender, or painful surface without skin lines ( Figures 3-27, 3-28, and 3-29 ). The process usually stops shortly before the distal interphalangeal joint is reached ( Figures 3-30 and 3-31 ). Fingertip eczema may last for months or years and is resistant to treatment. Topical steroids with or without occlusion give only temporary relief. Once allergy and psoriasis have been ruled out, fi ngertip eczema should be managed the same way as subacute and chronic eczema, by avoiding irritants and lubricating frequently. Elidel or Protopic is sometimes effective; tar creams applied twice each day have at times provided relief.

Pompholyx

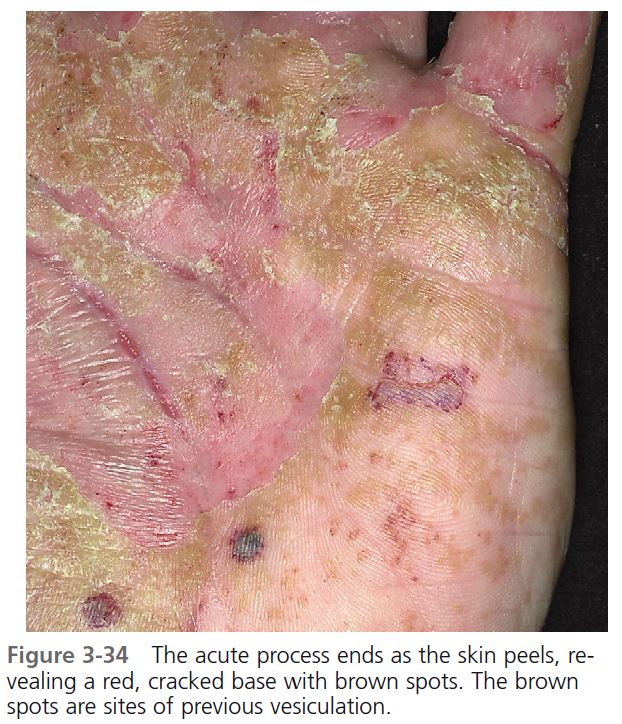

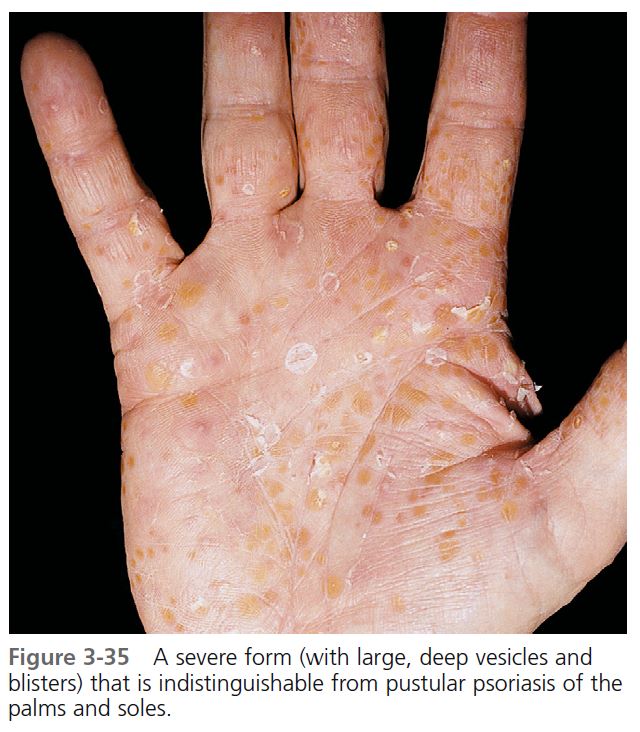

Pompholyx (dyshidrosis) is a distinctive reaction pattern of unknown etiology presenting as symmetric vesicular hand and foot dermatitis ( Figure 3-32 ). Moderate to severe itching precedes the appearance of vesicles on the palms and sides of the fingers ( Figure 3-33 ). The palms may be red and wet with perspiration, hence the name dyshidrosis. The vesicles slowly resolve in 3 to 4 weeks and are replaced by 1- to 3-mm rings of scale ( Figures 3-34 and 3-35 ). Chronic eczematous changes with erythema, scaling, and lichenification may follow. Waves of vesiculation may appear indefinitely. Pain rather than itching is the chief complaint. Pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles may resemble pompholyx, but the vesicles of psoriasis rapidly become cloudy with purulent fluid. Pustular psoriasis is chronic and the pustules do not evolve and disappear as rapidly as those of pompholyx. Patients with atopic dermatitis are affected as frequently as others.

ETIOLOGY. A recent study found the following causes of pompholyx in the 120 patients: mycosis (10.0%); allergic contact pompholyx (67.5%), with cosmetic and hygiene products as the main factor (31.7%), followed by metals (16.7%); and internal reactivation from drug, food, or haptenic (nickel) origin (6.7%). The remaining 15.0% of patients were classified as idiopathic patients, but all were atopic. PMID: 18086998 Ingestion of nickel, cobalt, and chromium can elicit pompholyx in patients who are patch test negative to these metals.

TREATMENT. Topical steroids; cold, wet compresses; and possibly oral antibiotics are used as the initial treatment, but the response is often disappointing. Short courses of oral steroids are sometimes needed to control acute fl ares. Resistant cases might respond to psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy. Patients (64%) who flared after oral challenge to metal salt cleared or markedly improved on diets low in the incriminated metal salt, and 78% of those patients remained clear when the diet was rigorously followed (a suggested diet for nickel-sensitive patients with pompholyx appears on p. 144 ). Attempts to control pompholyx with elimination diets may be worth a trial in difficult cases.

Patients with severe pompholyx who did not respond to conventional therapy or who had debilitating side effects from corticosteroids were treated with low-dose methotrexate (15 to 22.5 mg per week). PMID: 10188683 This led to significant improvement or clearing, and the need for oral corticosteroid therapy was substantially decreased or eliminated.

Id reaction

Intense inflammatory processes, such as active stasis dermatitis or acute fungal infections of the feet, can be accompanied by an itchy, dyshidrotic-like vesicular eruption (“id reaction”; Figure 3-36 ). These eruptions are most common on the sides of the fi ngers but may be generalized. The eruptions resolve as the inflammation that initiated them resolves. The id reaction may be an allergic reaction to fungi or to some antigen created during the inflammatory process. Almost all dyshidrotic eruptions are incorrectly called id reactions. The diagnosis of an id reaction should not be made unless there is an acute inflammatory process at a distant site and the id reaction disappears shortly after the acute inflammation is controlled.

ECZEMA: VARIOUS PRESENTATIONS

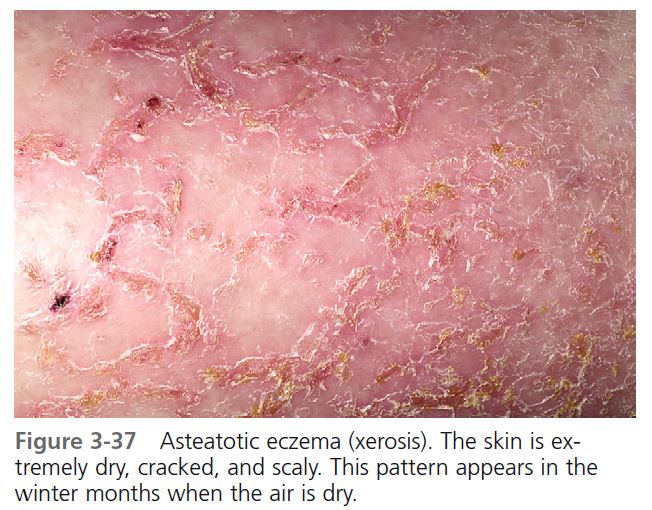

Asteatotic eczema

Asteatotic eczema (eczema craquelé) occurs after excess drying, especially during the winter months and among the elderly. Patients with an atopic diathesis are more likely to develop this distinctive pattern. The eruption can occur on any skin area, but it is most commonly seen on the anterolateral aspects of the lower legs. The lower legs become dry and scaly and show accentuation of the skin lines (xerosis) ( Figure 3-37 ). Red plaques with thin, long, horizontal superficial fissures appear with further drying and scratching ( Figure 3-38 ). Similar patterns of inflammation may appear on the trunk and upper extremities as the winter progresses. A cracked porcelain or “crazy paving” pattern of fissuring develops when short vertical fissures connect with the horizontal fi ssures. The term eczema craquelé is appropriately used to describe this pattern. The severest form of this type of eczema shows an accentuation of the previously described pattern with deep, wide, horizontal fissures that ooze and are often purulent ( Figure 3-39 ). Pain, rather than itching, is the chief complaint with this condition. Scratching or treatment with drying lotions such as calamine aggravates the eczematous inflammation and leads to infection with accumulation of crusts and purulent material.

TREATMENT. The initial stages are treated as subacute eczematous infl ammation with group III or IV topical steroid ointments. The severest form may have to be treated as acute eczema. The treatment involves wet compresses and antibiotics to remove crust and suppress infection before group V topical steroids and lubricants are applied. Wet compresses should be used only for a short time (1 or 2 days). Prolonged use of wet compresses results in excessive drying. Lubricating the dry skin during and after topical steroid use is essential. The use of oral steroids should be avoided; the disease fl ares within 1 or 2 days once they are discontinued.

Nummular eczema

Nummular eczema is a common disease of unknown cause that occurs primarily in the middle-aged and elderly. The typical lesion is a coin-shaped, red plaque that averages 1 to 5 cm in diameter ( Figure 3-40 ). The lesions can itch, and scratching often becomes habitual. In these cases, the term nummular neurodermatitis has been used. The plaque may become thicker and vesicles appear on the surface ( Figure 3-41 ); vesicles in ringworm, if present, are at the border. Unlike the thick, silvery scale of psoriasis, this scale is thin and sparse. The erythema in psoriasis is darker. Once the disease is established, lesions may become more numerous, but individual lesions tend to remain in the same area and do not increase in size. The disease is worse in the winter. The back of the hand is the most commonly involved site; usually only one lesion or a few lesions are present (see Figure 3-24 ). Other frequently involved areas are the extensor aspects of the forearms and lower legs, the fl anks, and the hips ( Figures 3-42 to 3-44 ). Lesions in these other sites tend to be more numerous. An extensive form of the disease can occur suddenly in patients with dry skin that is exposed to an irritating medicine or chemical, or in patients who have an active eczematous process at another site, such as stasis dermatitis on the lower legs. The lesions in these cases are round, faintly erythematous, dry, cracked, superficial, and usually confluent.

The course is variable, but it is usually chronic, with some cases resisting all attempts at treatment. Many cases become inactive after several months. Lesions may reappear at previously involved sites in recurrent cases.

TREATMENT. Treatment depends on the stage of activity; all stages of eczematous infl ammation may be present simultaneously. The red vesicular lesions are treated as acute, the red scaling plaques as subacute, and the habitually scratched thick plaques as chronic eczematous inflammation. Therefore group I to V topical steroids are intermittently used. Topical steroid foams may be especially effective. Foams with an emollient base such as Verdeso (desonide) or Olux-E (clobetasol) do not sting. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% used alone or intermittently with topical steroids may be tried.

CHAPPED FISSURED FEET

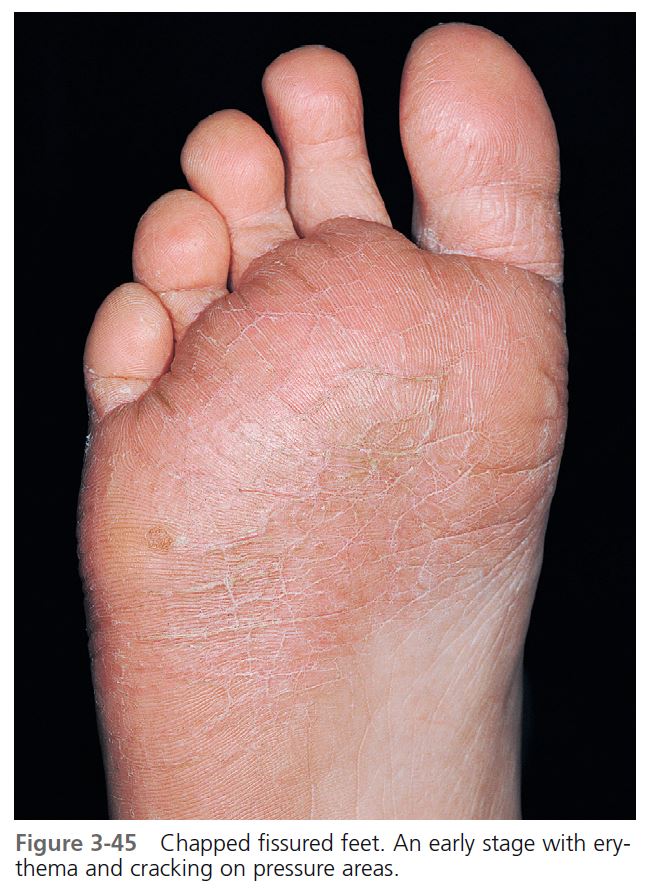

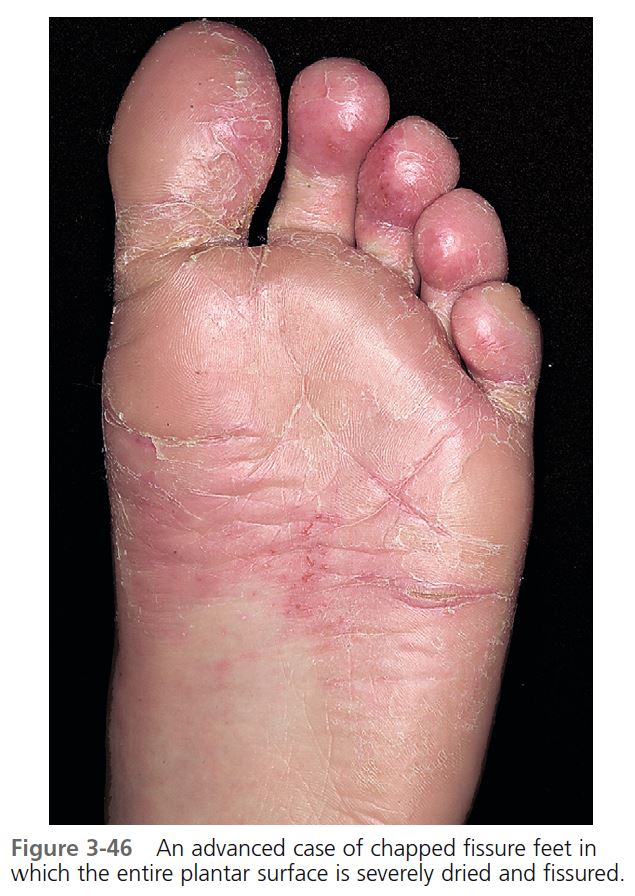

CLINICAL PRESENTATION. Chapped fissured feet (sweaty sock dermatitis, peridigital dermatitis, juvenile plantar dermatosis) are seen initially with scaling, erythema, fissuring, and loss of the epidermal ridge pattern. The tendency to severe chapping declines with age and is gone around the age of puberty. The mean age of onset is 7.3 years; the mean age of remission is 14.3 years. Onset is in early fall when the weather becomes cold and heavy socks and impermeable shoes or boots are worn. An artificial intertrigo is created when moist socks are kept in contact with the soles. The skin in pressure areas, toes, and metatarsal regions becomes dry, brittle, and scaly, and then fissured ( Figure 3-45 ). The chapping extends onto the sides of the toes. Eventually, the entire sole may be involved; sometimes the hands are also affected ( Figure 3-46 ).

The eruption lasts throughout the winter, clears without treatment in the late spring, and predictably recurs the next fall. Earlier descriptions referred to this entity as atopic winter feet in children, but the name has been changed to include patients who do not have atopic dermatitis. Atopic dermatitis of the feet in children occurs on the dorsal toes and usually not on the plantar surface, and it is itchy. The role of atopy is not yet defi ned. Children with chapped fissured feet complain of soreness and pain. Affected individuals must be predisposed to chapping because their wearing of moist socks and impermeable boots does not differ from that of unaffected children.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS. The differential diagnosis includes psoriasis, tinea pedis, and allergic contact dermatitis. The erythema in psoriasis is darker and the scales shed; the scales in chapped fissured feet are adherent, and removal of the scales causes bleeding. Tinea of the feet in children is rare. Feet with the rare case of familial Trichophyton rubrum are pale brown and have a fi ne scale. Fissuring is minimal, and there is little seasonal variation. Allergic contact dermatitis to shoes usually affects the dorsal aspect and spares the soles, webs, and sides of the feet. The eruption is bright red and scaly rather than pale red and chapped.

TREATMENT. Treatment is less than satisfactory. Topical steroids and lubrication provide some relief. Group II or III topical steroids are applied twice each day or, preferably, with plastic wrap occlusion at bedtime. Protopic ointment may be effective. PMID: 16681600 Lubricating creams are applied several times each day, especially directly after removing moist socks to seal in moisture. The feet should not be allowed to remain moist inside shoes. Preventive measures include changing into light leather shoes after removing boots at school and changing cotton socks one or two times each day.

SELF-INFLICTED DERMATOSES

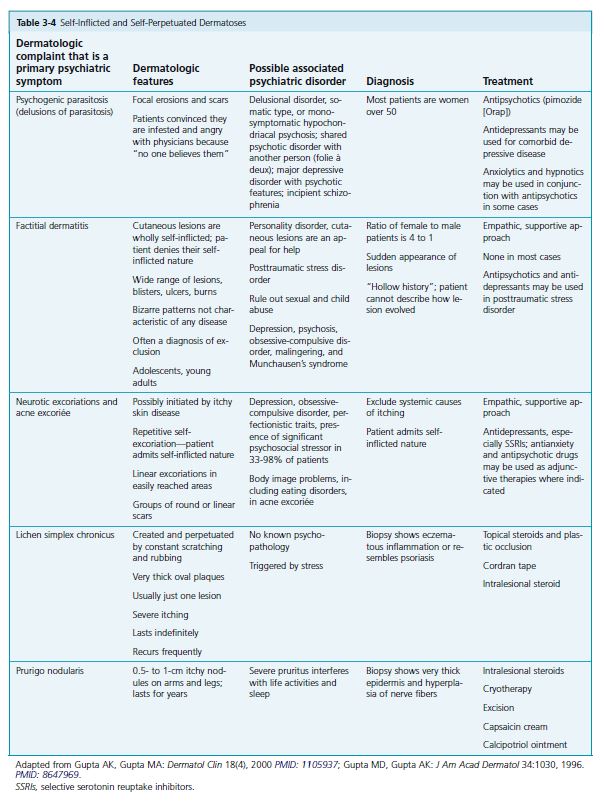

A number of skin disorders are created or perpetuated by manipulation of the skin surface ( Table 3-4 ). Patients may benefit from both dermatologic and psychiatric care. The most common self-inflicted dermatoses are discussed here.

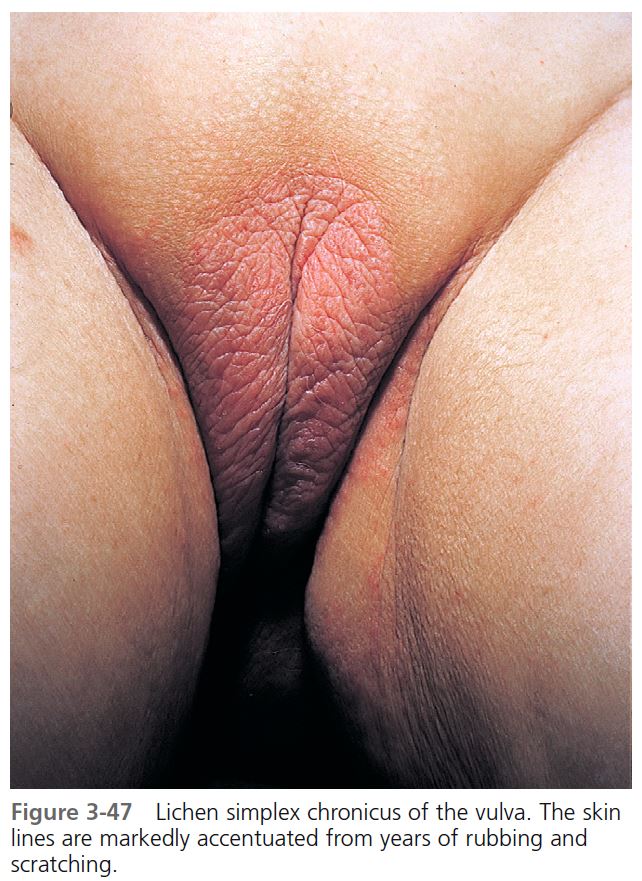

Lichen simplex chronicus

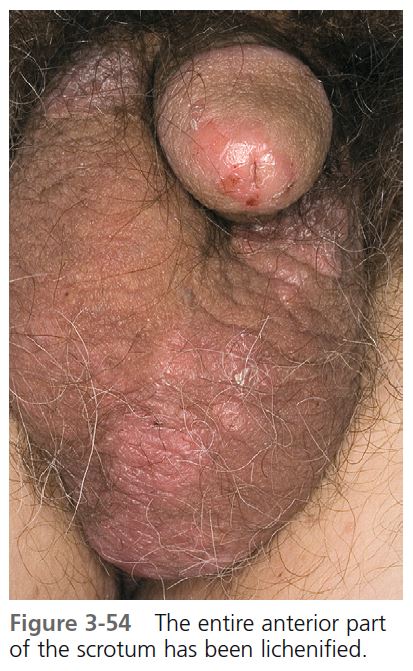

Lichen simplex chronicus ( Figures 3-47 through 3-54 ), or circumscribed neurodermatitis, is an eczematous eruption that is created by habitual scratching of a single localized area. The disease is more common in adults, but may be seen in children. The areas most commonly affected are those that are conveniently reached. These are listed in Box 3-7 in approximate order of frequency. Patients derive great pleasure in the relief that comes with frantically scratching the inflamed site. Loss of this pleasurable sensation or continued subconscious habitual scratching may explain why this eruption frequently recurs.

A typical plaque stays localized and shows little tendency to enlarge with time. Red papules coalesce to form a red, scaly, thick plaque with accentuation of skin lines ( lichenification ). Lichen simplex chronicus is a chronic eczematous disease, but acute changes may result from sensitization with topical medication. Moist scale, serum, crusts, and pustules are signs of infection.

Lichen simplex nuchae occur almost exclusively in women who reach for the back of the neck during stressful situations (see Figure 3-51 ). The disease may spread beyond the initial well-defined plaque. Diffuse dry or moist scale, crust, and erosions extend into the posterior scalp beyond the neck. Secondary infection is common. Nodules, usually less than 1 cm and scattered randomly in the scalp, occur in patients who frequently pick at the scalp; there may be few nodules or many.

CHRONIC VULVAR ITCHING

Women who have chronic vulvar itching usually have eczema. The degree of itching may not correspond to the appearance of the skin. Scratching begins a cycle that makes the skin rough, red, and irritated, producing more itching. Lichen sclerosus, contact dermatits, lichen planus, psoriasis, and Paget’s disease are other causes of itching. A 2- to 4-week course of a group I topical steroid is usually very effective.

RED SCROTUM SYNDROME

Lichen simplex of the scrotum is a common fi nding, and thickened skin with accentuated skin markings is typical. Some patients present with persistent redness of the anterior half of the scrotum that may involve the base of the penis ( Figure 3-55 ). There is persistent itching, burning, or pain. The cause is unknown and it is resistant to treatment. Some men present with erythema of the anterior scrotum and have no symptoms. This is a variant of normal.

TREATMENT. The patient must first understand that the rash will not clear until even minor scratching and rubbing are stopped. Scratching frequently takes place during sleep,

and the affected area may have to be covered. Lichen simplex chronicus is chronic eczema and is treated as outlined in the section on eczematous infl ammation. Clobetasol

foams are very effective and can be used for lesions on the neck, legs, wrists, ankles, and vulva. Treatment of the anal area or the fold behind the ear does not require potent

topical steroids as do other forms of lichen simplex; rather, these intertriginous areas respond to group V or VI topical steroids. Lichen simplex nuchae, because of its location, is

difficult to treat. Infl ammation that extends into the scalp may be treated with a group II steroid gel such as fluocinonide applied twice each day. Moist, secondarily infected areas respond to oral antibiotics and topical steroid solutions (e.g., clobetasol solution). A 2- to 3-week course of prednisone (20 mg twice daily) should be considered when an extensively inflamed scalp does not respond rapidly to topical treatment. Nodules caused by picking at the scalp may be very resistant to treatment, requiring monthly intralesional injections with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog 10 mg/ml). Botulinum toxin A injected intradermally into lichenifi ed lesions may block acetylcholine release and control pruritus.

Prurigo nodularis

Prurigo nodularis is an uncommon disease of unknown cause that may be considered a nodular form of lichen simplex chronicus. There is intractable pruritus. It resembles picker’s nodules of the scalp except that the few to 20 or more nodules are randomly distributed on the extensor aspects of the arms and legs ( Figures 3-56 and 3-57 ). They are created by repeated scratching. The nodules are red or brown, hard, and dome-shaped with a smooth, crusted, or warty surface; they measure 1 to 2 cm in diameter. Hypertrophy of cutaneous papillary dermal nerves is a relatively constant feature. Complaints of pruritus vary. Some patients claim there is no itching and that scratching is only habitual, whereas others complain that the pruritus is intense.

TREATMENT. Prurigo nodularis is resistant to treatment and lasts for years. As with picker’s nodules of the scalp, repeated intralesional steroid injections may be effective. Excision of individual nodules is sometimes helpful. Cryotherapy is sometimes successful. Capsaicin 0.025% (Zostrix cream) and capsaicin 0.075% HP (Zostrix-HP cream) interfere with the perception of pruritus and pain by depletion of neuropeptides in small sensory cutaneous nerves. Application of the cream four to six times daily for up to 10 months resulted in cessation of burning and pruritus. Lesions gradually heal. The use of combination or sequential topical calcipotriene with topical steroids has been effective. Naltrexone (50 mg daily), an orally active opiate antagonist, was found to be effective therapy for pruritic symptoms in many diseases. Oral cyclosporine (3 to 5 mg/kg daily) was effective in one study. PMID: 18445069 Gabapentin has been used in resistant cases. PMID: 18086601 Depression and dissociative experiences may be associated with this disorder and psychiatric referral may be appropriate.

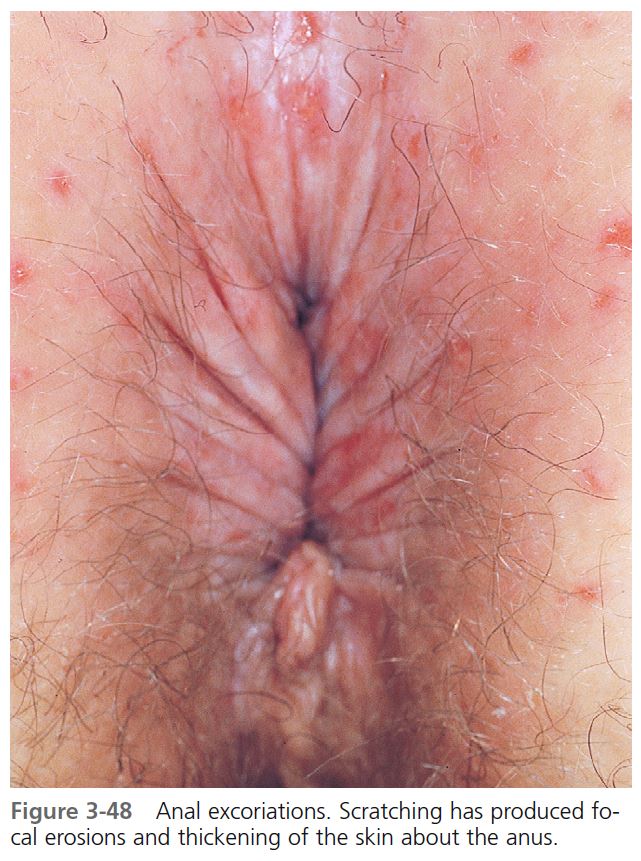

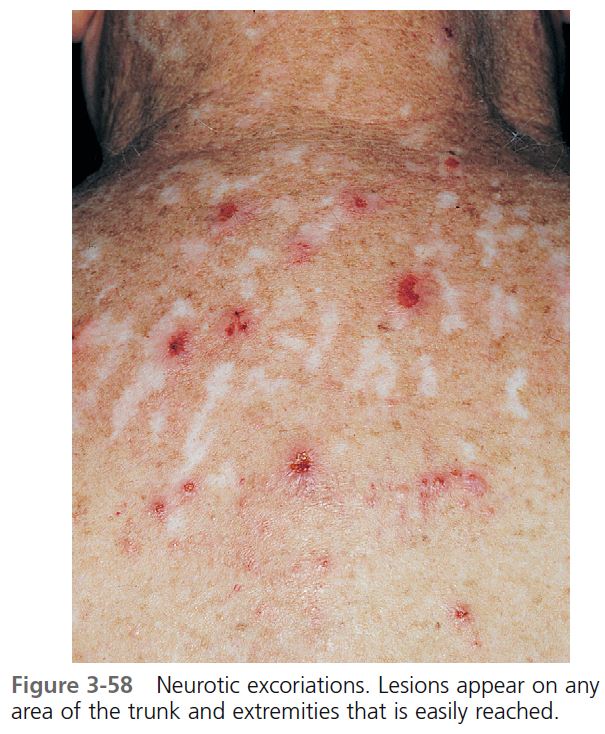

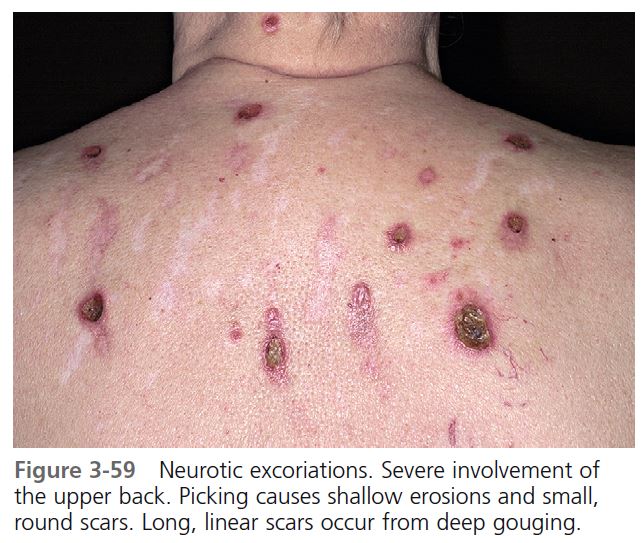

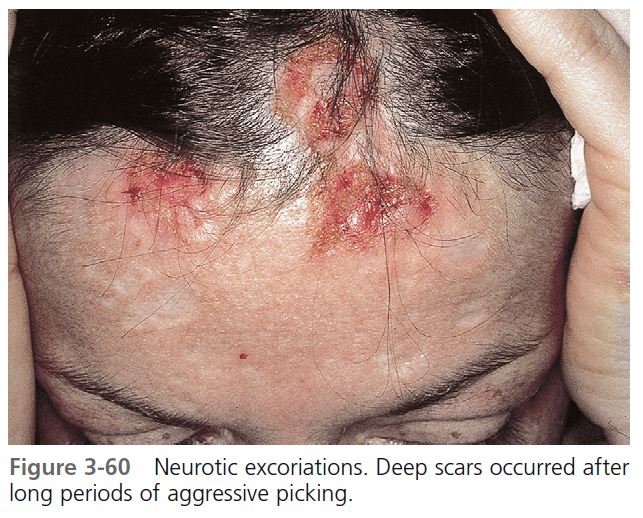

Neurotic excoriations

Neurotic excoriations are patient-induced linear excoriations. Patients dig at their skin to relieve itching or to extract imaginary pieces of material that they feel is imbedded in or extruding from the skin. Itching and digging become compulsive rituals. Most patients are aware that they create the lesions. The most consistent psychiatric disorders reported are perfectionistic and compulsive traits; patients manifest repressed aggression and self-destructive behavior. Depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, somatoform disorders, mania, psychosis, and substance abuse have also been associated with itch. Recurrent and intrusive thoughts lead to compulsive skin picking. Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a common comorbid condition. Excoriation is preceded by increased tension and anxiety followed by gratifi cation or relief when excoriating the skin.

CLINICAL APPEARANCE. Repetitive scratching and digging produces few to several hundred excoriations; all lesions are of similar size and shape. They tend to be grouped in areas that are easily reached, such as the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, abdomen, thighs, and upper parts of the back and shoulders, with the face being the most common site ( Figures 3-58 through 3-60 ). These vary from a few to several hundred and vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Recurrent picking at crusts delays healing. Groups of white scars surrounded by brown hyperpigmentation are typical; their presence alone can indicate past difficulty.

TREATMENT. The use of group I topical steroids applied twice a day or group V topical steroids under plastic wrap occlusion combined with systemic antibiotics produces gratifying results. Resistant lesions are treated with monthly intralesional injections with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog 10 mg/ml). Frequent lubrication and infrequent washing with only mild soaps should be encouraged once areas are healed. Patients should try to substitute the ritual of applying lubricants for the ritual of digging. An empathic, supportive approach has been reported to be significantly more effective than insight-oriented psychotherapy, which often exacerbates the symptoms. Psychiatric referral is appropriate for patients who fail the supportive approach. Those with depression may be treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), doxepin, and psychotherapy. Obsessive-compulsive disorders are treated with SSNRIs, SSRIs, TCAs and behavioral therapy. PMID: 18318883

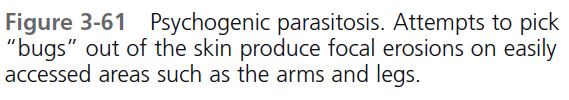

PSYCHOGENIC PARASITOSIS

Patients with psychogenic parasitosis (delusions of parasitosis) believe they are infested with parasites. They move from one physician to another looking for someone who will believe them. A variety of psychiatric disorders may be associated with this disorder, but suggesting psychiatric referral may offend the patient. A supportive, therapeutic relationship is essential.

THE DELUSION. Patients report seeing and feeling parasites. Involvement of the ears, eyes, and nose is common. They present with the “matchbox” sign, in which small bits of excoriated skin, dried blood, debris, or insect parts are brought in matchboxes or other containers as “proof” of infestation. Body fl uids thought to contain parasites are brought in jars. Pest control offi cers may have been hired to rid the house of parasites.

THE SKIN. Excoriations and ulcers and linear scars are common on easily reached areas of the forearms, legs, trunk, and face ( Figure 3-61 ).

CLASSIFICATION. Classify patients with psychogenic parasitosis into four groups: anxiety/hypochondriasis, anxiety/hypochondriasis with depression, delusional parasitosis, and delusional parasitosis with depression. Patients suffering from anxiety/hypochondriasis may believe that they are infested by parasites but may also express doubt about their infestation, express fears of “going crazy,” and agree that parasites may not be present. Patients with anxiety/hypochondriasis and depression may agree to undergo a psychiatric evaluation. Patients who have a true delusion are convinced that they have a parasitic infestation that none of the physicians can fi nd; these patients may have an underlying major depression.

MANAGEMENT. A majority of patients with short-term illness can be cured with suggestion; the remainder have a true delusion. Patients with symptoms for over 3 months are usually not cured by suggestion alone. Listen and show concern; examine the skin with magnifi cation and prepare scrapings; rule out true infestation. Animal and bird mites and scabies may actually be present. Do not suggest that the diagnosis is obvious on the fi rst visit. The second visit can be lengthy. Collect specimens brought in by the patient and set them aside for later evaluation. Conduct a thorough examination and listen for indicators of depression. After two or more visits patients may suggest that this may be “all in my head.” At this point, explain that some patients actually see and feel parasites that are not real. Explain that this is an illness that affects sane people. The clinician may sense that the patient doubts the existence of the infestation (i.e., the belief is shakable). The patient is then offered a benzodiazepine to help with anxiety while waiting for the next visit 2 weeks later; a psychiatric referral is suggested at that 2-week follow-up visit.

Patients whose belief is unshakable are considered to have a delusional disorder. Suggest psychiatric referral. Explain that many other patients with similar symptoms have been helped with this treatment and that the medication can be taken as a “therapeutic trial.” Antipsychotics (e.g., pimozide, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine) are usually prescribed by the psychiatrist.

STASIS DERMATITIS AND VENOUS ULCERATION: POSTPHLEBITIC SYNDROMES

Stasis dermatitis

ETIOLOGY. Stasis dermatitis is an eczematous eruption that occurs on the lower legs in some patients with venous insufficiency. The dermatitis may be acute, subacute, or chronic and recurrent, and it may be accompanied by ulceration. Most patients with venous insufficiency do not develop dermatitis, which suggests that genetic or environmental factors may play a role. The reason for its occurrence is unknown. Some have speculated that it represents an allergic response to an epidermal protein antigen created through increased hydrostatic pressure, whereas others believe that the skin has been compromised and is more susceptible to irritation and trauma.

ALLERGY TO TOPICAL AGENTS. Patients with stasis dermatitis have signifi cantly more positive reactions when patch tested with components of previously used topical agents. Topical medications that contain potential such as lanolin, benzocaine, parabens, and neomycin should be avoided by patients with stasis disease. Allergy to corticosteroids in topical medication is also possible.

Types of eczematous inflammation

SUBACUTE INFLAMMATION

Subacute inflammation usually begins in the winter months when the legs become dry and scaly. Brown staining of the skin (hemosiderin) may have appeared slowly for months ( Figure 3-62 ). The pigment is iron left after disintegration of red blood cells that leaked out of veins because of increased hydrostatic pressure. Scratching induces first subacute and then chronic eczematous inflammation. Attempts at self-treatment with drying lotions (calamine) or potential sensitizers (e.g., neomycin containing topical medicines) exacerbate and prolong the inflammation.

ACUTE INFLAMMATION

A red, superficial, itchy plaque may suddenly appear on the lower leg. This acute process may be eczematous inflammation, cellulitis, or both. Weeping and crusts appear ( Figure 3-63 ). A vesicular eruption (id reaction) on the palms, trunk, and/or extremities sometimes accompanies this acute inflammation. The inflammation responds to systemic antibiotics, wet compresses, and group III to V topical steroids. Wet compresses should be discontinued before excessive drying occurs. The id reaction resolves spontaneously as the primary site improves.

CHRONIC INFLAMMATION

Recurrent attacks of inflammation eventually compromise the poorly vascularized area, and the disease becomes chronic and recurrent ( Figures 3-64 and 3-65 ). The typical presentation is a cyanotic red plaque over the medial malleolus. Fibrosis following chronic inflammation leads to permanent skin thickening. The skin surface in these irreversibly changed areas may have a bumpy, cobblestone appearance that results from fi brosis and venous and lymph stasis. The skin remains thickened and diffusely dark brown (postinfl ammatory hyperpigmentation) during quiescent periods.

TREATMENT OF STASIS DERMATITIS

Topical steroids and wet dressings. The early, dry, superficial stage is managed as subacute eczematous inflammation with group II to V topical steroid creams or ointments and lubricating creams or lotions. Oral antibiotics (usually those active against Staphylococci, e.g., cephalexin) hasten resolution if cellulitis is present. Moist exudative infl ammation and moist ulcers respond to tepid wet compresses of Burow’s solution or just saline or water for 30 to 60 minutes several times a day. Wet dressings suppress infl ammation while debriding the ulcer. Adherent crust may be carefully freed with blunt-tipped scissors. Group V topical steroids are applied to eczematous skin at the periphery of the ulcer. Patients must be warned that steroid creams placed on the ulcer stop the healing process. Elevation of the legs encourages healing.

Venous leg ulcers

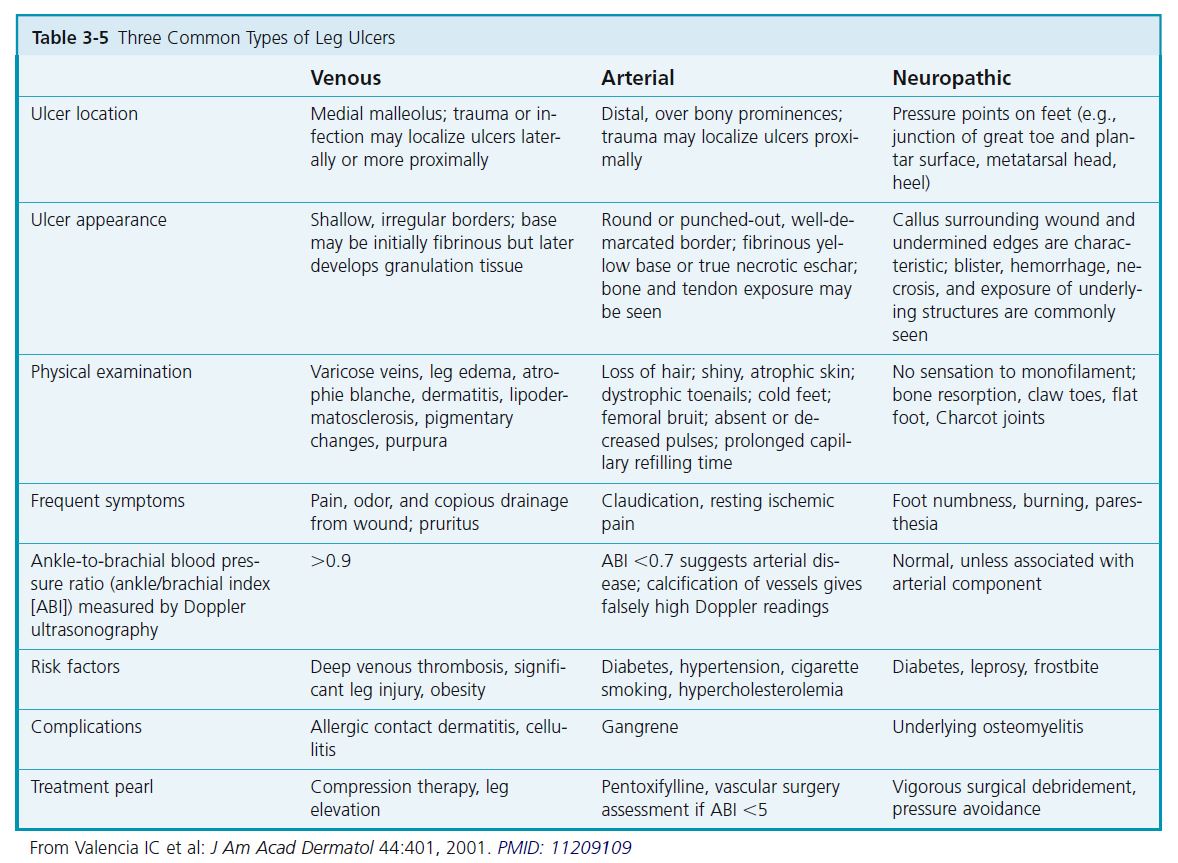

The three main types of lower-extremity ulcers are venous, arterial, and neuropathic ( Table 3-5 ). Most leg ulcers are venous; foot ulcers are more often caused by arterial insufficiency or neuropathy. Most venous ulcers are located over the medial malleolus and are often larger than other ulcers. Diabetes is a common underlying condition.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS. Many diseases cause leg ulcers ( Box 3-8 ). Biopsy (basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas) and culture (fungal, atypical mycobacterial) chronic ulcers that do not respond to conventional therapy. Vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus may be associated with lower-extremity ulcers.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY. The leg has superficial, communicating, and deep veins. The superficial system contains the long (medial) and short (lateral) saphenous veins. Perforator veins connect the superfi cial veins to the deep venous system. Normally blood flows from the superficial to the deep system. Venous hypertension (“chronic venous insufficiency”) occurs if any of the valves dysfunction, a thrombosis blocks the deep system, or there is calf muscle pump failure. Increased pressure causes diffusion of substances, including fibrin, out of capillaries. Fibrotic tissue may predispose the tissue to ulceration.

ETIOLOGY AND LOCATION. Venous insufficiency followed by edema is the fundamental change that predisposes to dermatitis and ulceration. Venous insufficiency occurs when venous return in the deep, perforating, or superficial veins is impaired by vein dilation and valve dysfunction. Deep vein thrombophlebitis, which may have been asymptomatic earlier, is the most frequent precursor of lower leg venous insufficiency. Blood pools in the deep venous system and causes deep venous hypertension and dilation of the perforators that connect the superfi cial and deep venous systems. Venous hypertension is then transmitted to the superficial venous system. The largest perforators are posterior and superior to the lateral and medial malleoli. These are the same areas where dermatitis and ulceration are most prevalent. Superficial varicosities alone are unlikely to produce venous insufficiency.

CLINICAL FEATURES. Ulceration is almost inevitable once the skin has been thickened and circulation is compromised. Ulceration may occur spontaneously or after the slightest trauma ( Figure 3-66 ). The ulcer may remain small or may enlarge rapidly without any further trauma. A dull, constant pain that improves with leg elevation is present. Pain from ischemic ulcers is more intense and does not improve with elevation.

Ulcers have a sharp or sloping border and are deep or superficial. Removal of crust and debris reveals a moistbase with granulation tissue. The base and surrounding skin are often infected. Healing is slow, taking several weeks or months. After healing, it is not uncommon to see ulcers rapidly recur. The ulcers are replaced with ivorywhite sclerotic scars. Despite the pain and the inconvenience of treatment, most patients tolerate this disease well and remain ambulatory.

CHANGES IN SURROUNDING SKIN. Edema is a common finding; it is usually pitting and disappears at night with elevation. Chronic edema, trauma, infection, and inflammation lead to subcutaneous tissue fi brosis, giving the skin a firm, nonpitting, “woody” quality. Fat necrosis may follow thrombosis of small veins, and this may be the most important underlying change that predisposes to ulceration. Recurrent ulceration and fat necrosis is associated with loss of subcutaneous tissue and a decrease in lower leg circumference (lipodermatosclerosis). Advanced disease is represented by an “inverted bottle leg,” in which the proximal leg swells from chronic venous obstruction and the lower leg shrinks from chronic ulceration and fat necrosis.

STASIS PAPILLOMATOSIS. Stasis papillomatosis is a condition usually found in chronically congested limbs. Lesions vary from small to large plaques that consist of aggregated brownish or pinkish papules with a smooth or hyperkeratotic surface ( Figures 3-67 and 3-68 ). The lesions most frequently affect the dorsum of the foot, the toes, the extensor aspect of the lower leg, or the area surrounding a venous ulcer. This condition occurs in patients with local lymphatic disturbances; patients with primary lymphedema, chronic venous insufficiency, trauma, and recurrent erysipelas are at greatest risk.

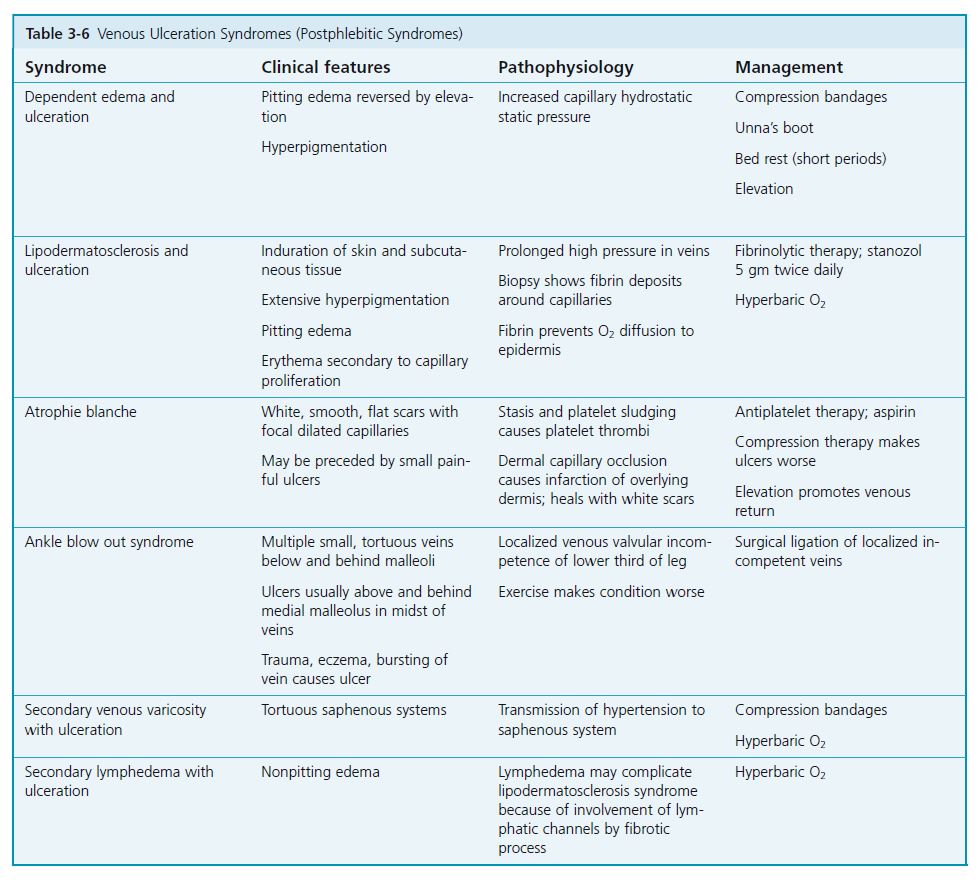

POSTPHLEBITIC SYNDROMES (CLINICAL VARIANTS). Impairment of venous return leads to increased hydrostatic pressure and interstitial fluid accumulation. Six clinical variants ( Table 3-6 ) occur with venous hypertension.

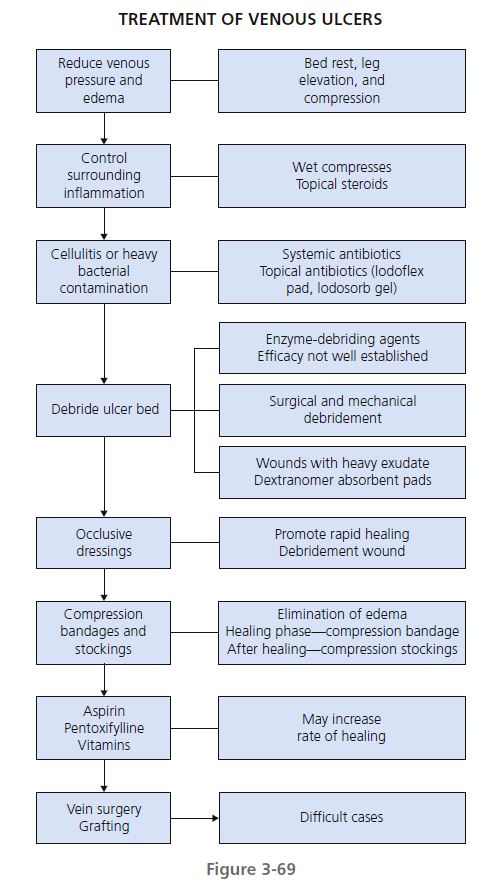

MANAGEMENT OF VENOUS ULCERS

INITIAL EVALUATION AND TREATMENT. Once other causes of lower leg ulcers have been excluded, the area around the ulcer must be prepared for defi nitive treatment. Ulcers do not heal if edema, infection, or eczematous inflammation is present. The venous system should be investigated. Surgery or sclerotherapy may be needed to control venous reflux.

VARICOSE VEINS. Varicose veins are superficial vessels that are caused by defective venous valves. Perforator vein incompetence may lead to ulceration. Varicose veins cause venous hypertension that leads to edema, cutaneous pigmentation, stasis dermatitis, and ulceration. The goal of therapy is to normalize venous physiology. Deep venous hypertension is managed with compression therapy. Sclerotherapy is used to treat isolated perforator incompetence, even through an ulcer if necessary. Saphenous vein insufficiency is usually managed by surgery.

LABORATORY EVALUATION. Initial evaluation includes complete blood count (CBC), blood glucose level, and sedimentation rate. Consider curet or biopsy of the ulcer for bacterial culture. Biopsy the edge of ulcers that do not heal with conventional therapy to rule out basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma. Radiograph deep ulcers to rule out osteomyelitis.

FUNCTION STUDIES. Doppler, plethysmography, and duplex scanning are used to characterize venous abnormalities in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Continuous-wave Doppler studies are useful in providing information on the anatomic level of any superficial venous incompetence or obstruction; however, it can be difficult to differentiate superficial from deep venous insufficiency. Plethysmography is a simple test to measure the venous refl ux degree and the calf muscle pump efficiency. Image ultrasound associated with pulsated Doppler ultrasound, known as duplex scanning, is a method that provides detailed anatomic information, and is especially useful in identifying which veins are competent. These characteristics enable duplex scanning to substitute for phlebography because duplex scanning is noninvasive and avoids radiological contrasts, showing both anatomic and functional features (reflux or obstruction) of the venous system. It is the examination of choice to assess the superficial, deep, and perforating systems. PMID: 15941430

TREATMENT. Hospital-based wound care clinics are available for treatment. Venous pressure and leg edema can be reduced with bed rest, leg elevation, and compression. Contributing systemic disease, local infection, and inflammation should be treated ( Figure 3-69 ). Stop cigarette smoking and excessive alcohol intake. Encourage good nutrition. Multivitamin supplements that contain vitamins C and E and zinc may help.

LEG ELEVATION. Venous hypertension must be reversed. Bed rest and leg elevation are effective. Elevation of the legs above the heart level for 30 minutes, three to four times per day, allows swelling to subside. Leg elevation at night is accomplished by raising the foot end of the patient’s bed on blocks 15 to 20 cm high.

INFLAMMATION SURROUNDING THE ULCER. Tepid saline or silver nitrate (0.5%) wet compresses rapidly control infl ammation. Silver nitrate is preferred when infection is present. Fresh compresses (replaced hourly) should be kept in place almost continuously for 24 to 72 hours. Fluids should not be added to dressings that are in place. Group V topical steroids are applied two to four times each day and may be covered with the compress. Patients with venous ulcers are prone to developing allergic reactions to topical medications in the surrounding compromised skin. Neomycin, paraben preservatives, and lanolin should be avoided. If inflammation persists after appropriate treatment, patch testing should be undertaken.

SYSTEMIC ANTIBIOTICS. Ulcers are typically contaminated with different aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, but routine administration of systemic antibiotics does not increase healing rates. Topical and/or systemic antibiotics may enhance wound healing when heavy bacterial contamination is present. Cellulitis must be treated with systemic antibiotics (see Chapter 9 ). Stasis dermatitis and cellulitis have a similar appearance and are often confused. Stasis dermatitis may act as a reservoir for infection. Dermatitis is easily treated with short courses of group I to IV topical steroids.

TOPICAL ANTIBIOTICS. Cadexomer-iodine (Iodoflex pad, Iodosorb gel) preparations have antimicrobial properties, debride wounds, and stimulate granulation tissue; other topical antiseptics may be toxic for wounds.

DEBRIDEMENT OF ULCER BED. Once cellulitis and eczematous infl ammation have been controlled, the ulcer must be prepared for defi nitive treatment. Exudate and crust must be removed to expose granulation tissue, the foundation for new epithelium.

Wound debridement. Ulcers should be debrided of necrotic and fi brinous debris. Occlusive dressing, chemical debridement, and surgical and mechanical debridement are three methods that help to remove necrotic tissue and promote granulation tissue.

Occlusive dressings. Occlusive dressings promote rapid healing of leg ulcers. Many products are available; the choice is usually determined by the type of wound and the amount of exudate. These dressings should be used with compression for maximum benefit. Wound care clinics are profi cient in the application of these dressings.

Chemical debridement. Enzyme-debriding agents may be considered to remove necrotic tissue. Santyl (collagenase), Panafi l (papain), Granulex (trypsin), or Accuzyme is applied one or several times each day. The efficacy of all of these agents is not well established; Elase is ineffective.

Surgical or mechanical debridement. Debridement with sharp surgical instruments must be performed with great care so as not to damage delicate viable tissue. Whirlpool, wound irrigation, wet dressings, and hydrotherapy are all commonly used.

DEFINITIVE TREATMENT

1. Measure the ulcer at each visit.

2. Encourage elevation and periods of exercise and ambulation.

3. Minimize bacteria and necrotic debris.

4. Promote granulation tissue formation.

5. Induce reepithelialization.

6. Reduce edema.

7. Protect from trauma.

COMPRESSION. Compression is the cornerstone of therapy for venous ulcers. Elimination of edema is essential during treatment and after resolution. This is accomplished by applying external compression bandages during the healing phase and graded compression stockings after healing to prevent recurrence. Compression bandages can be applied over occlusive dressing during the healing phase. Some patients may have arterial insuffi ciency, as well as venous disease. Measure the ankle-brachial pressure index before compression to avoid necrosis or gangrene of the foot.

Compression bandages. Compression therapy and maintenance of a moist wound environment are essential. Compression improves venous hypertension and relieves edema. An external pressure of at least 35 to 40 mm Hg at the ankle is desirable. Many bandage systems are available.

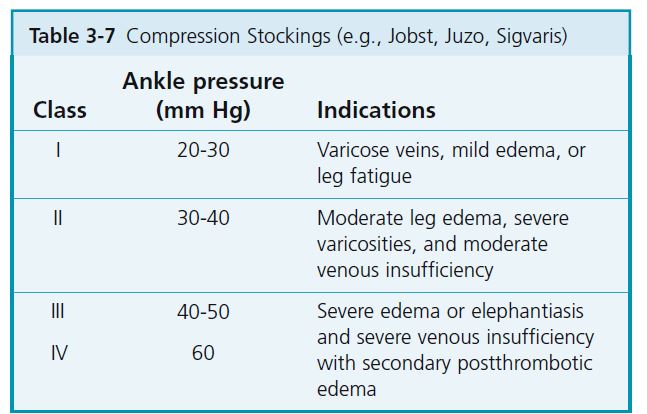

GRADED ELASTIC COMPRESSION STOCKINGS. These stockings exert high pressure at the ankle, with pressure decreasing to the thigh. After healing, compression stockings should be worn to prevent ulcer recurrence. These stockings are put on in the morning soon after the patient gets out of bed. Patients with arthritis who have difficulty putting these stockings on may use the zip-up type. The amount of compression can be specifi ed by the physician (see Table 3-7 ). Patients with chronic venous insufficiency who have had stasis dermatitis or ulceration require a compression of between 35 and 40 mm Hg. Various lengths can be purchased; an above-the-knee stocking may give the best results but knee-high stockings are most commonly used. The stockings may be difficult for older patients to put on; also, the stockings must be replaced periodically because they may stretch, thereby losing elasticity. Firmly applied Ace bandages are a less effective but convenient alternative.

There are four classes of stockings based on the compression exerted at the ankle.

Nonelastic bandages. Unna’s boots (e.g., Dome Paste, Gelocast Bandage, Unna-Flex) are gauze bandages impregnated with zinc oxide paste to create a semirigid “boot” when applied. They protect ulcers from the environment and help control edema and are especially helpful in elderly or noncompliant patients because they can be left in place for 7 to 10 days. Because such a bandage does not eliminate existing edema fl uid, it should be applied in the morning after edema has drained. However, when ulcers produce a large amount of exudate, the boot should be changed more often. Unna’s boots are not applied over synthetic dressings.

Pneumatic compression pumps. Intermittent compression pumps are considered when a venous ulcer does not respond to treatment with standard compression dressings.

ASPIRIN. Oral enteric-coated aspirin (300 mg) increased the rate of venous ulcer healing.

Pentoxifylline. Pentoxifylline (800 mg three times a day) accelerated the healing rate of venous ulcers and was more effective than the conventional dose (400 mg three times a day).

Vitamins. Patients with signs of malnutrition, such as low serum albumin or transferrin concentrations, may benefi t from dietary supplementation. Ascorbic acid (1 to 2 gm/day), zinc sulfate (220 mg three times a day), and vitamin E (200 mg/day) may be used for supplementation. These vitamins are essential for wound healing but should not be prescribed in excessively high dosages.

Grafting. Skin grafts promote healing even if they do not take because they stimulate wound epithelialization. Split-thickness skin grafting is used for large ulcers. Meshed grafts are useful for large ulcers because they allow exudate to escape through the graft interstices. The donor site may be painful and slow to heal, especially in elderly patients. Pinch grafting is useful for smaller wounds. Multiple small pinches or superfi cial punch biopsies are taken from a donor site (e.g., thigh) and placed dermal side down on the ulcer bed. The tissue-engineered human skin equivalent Apligraf is effective for treating long-standing deep ulcers.

Vein surgery. Ligation or sclerosis of the long and short saphenous systems, with or without communicating vein ligation or sclerosis, is useful only if the deep veins are competent. Superficial vein surgery does not improve the healing rate of venous ulcers.