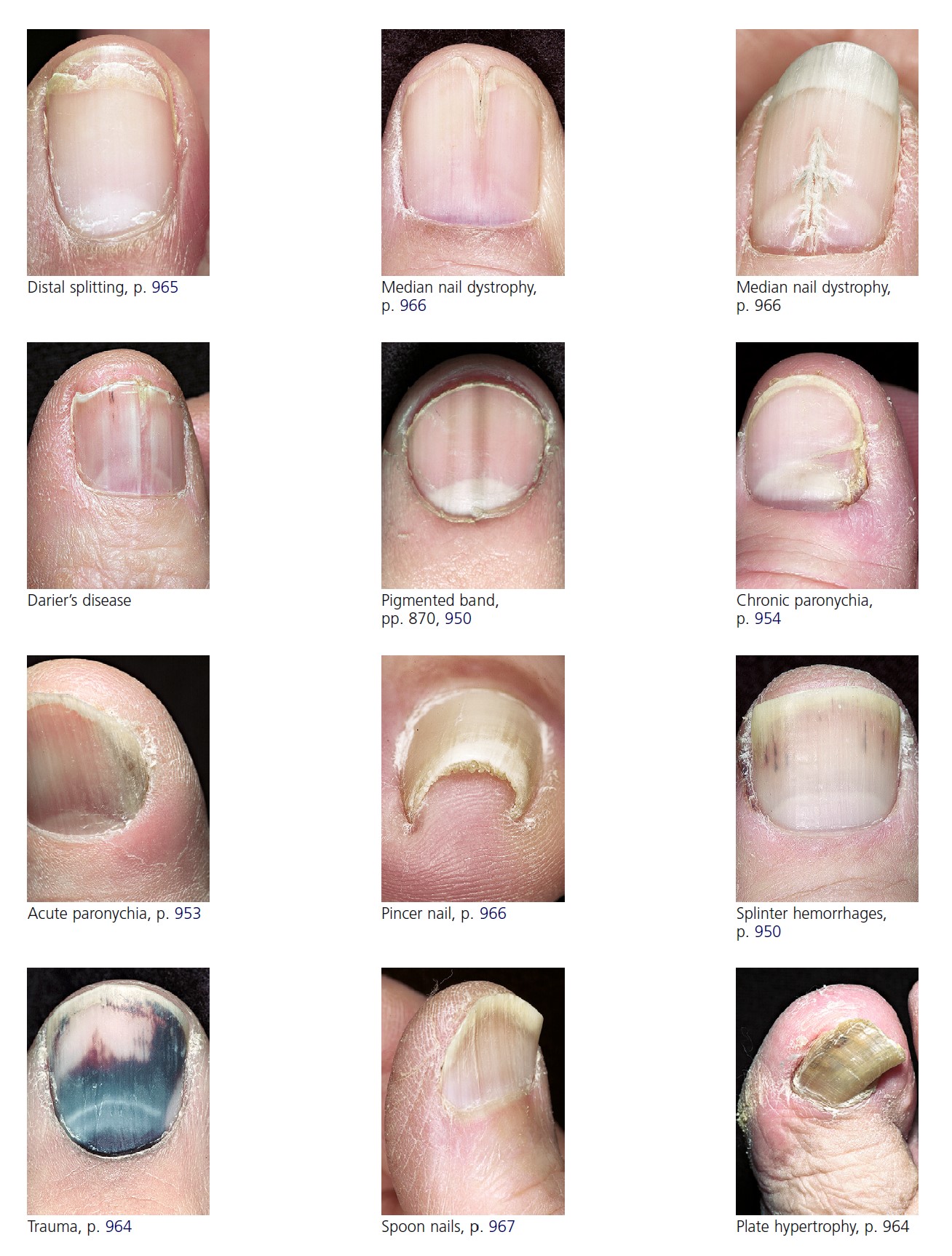

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

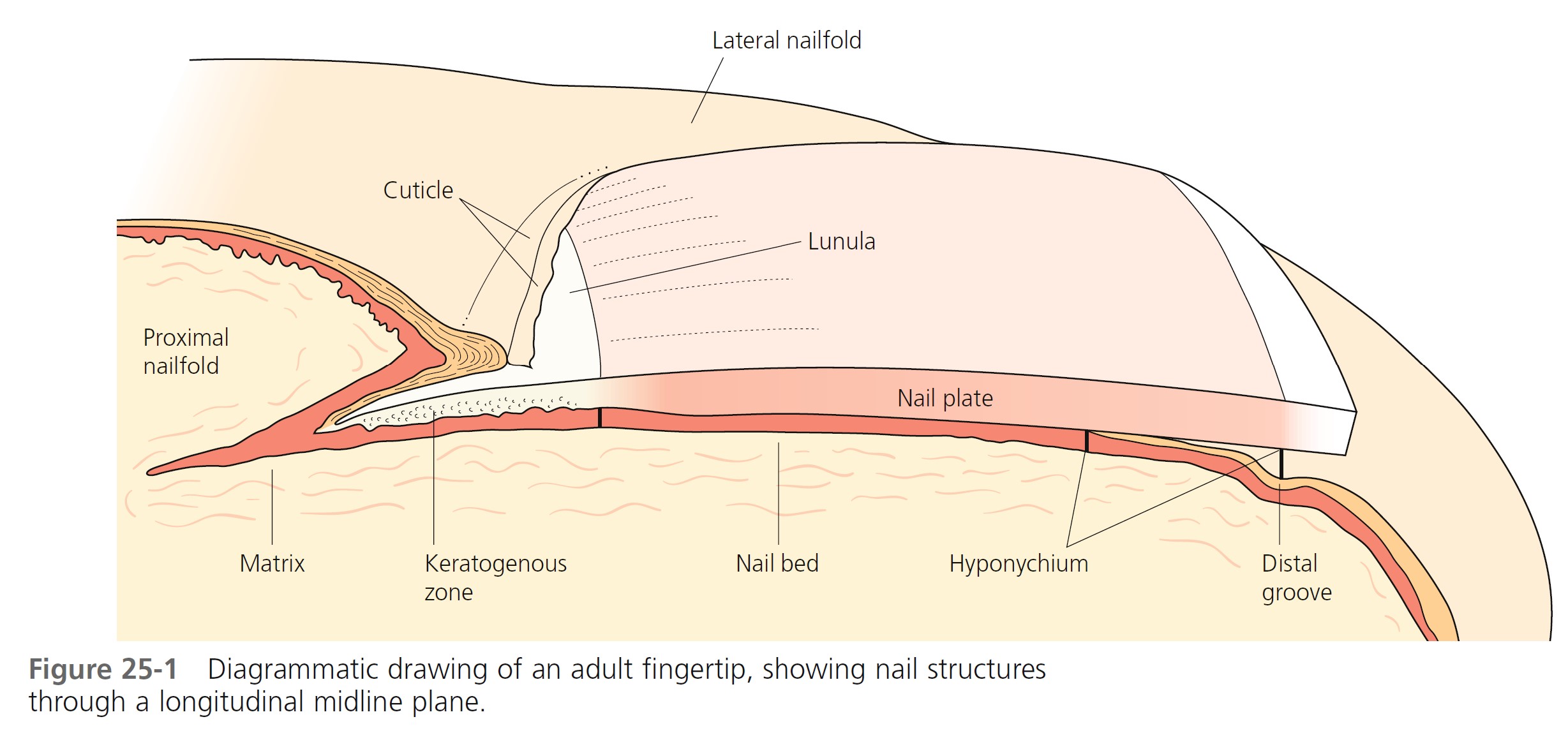

ANATOMY. The nail unit consists of several components ( Figure 25-1 ). The nail plate is hard, translucent, dead keratin. The nailfold includes the skin surrounding the lateral and proximal aspects of the nail plate. The proximal nailfold overlies the matrix. Its keratin layer extends onto the proximal nail plate to form the cuticle. Capillary loops at the tip of the proximal nailfold are normally small and inapparent, but they become distinct in diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and scleroderma. The proximal nailfold epithelium covers the proximal nail plate for a few millimeters and then makes a 180-degree turn and curves back into direct contact with the nail plate. It makes another 180-degree turn and becomes continuous with the nail matrix.

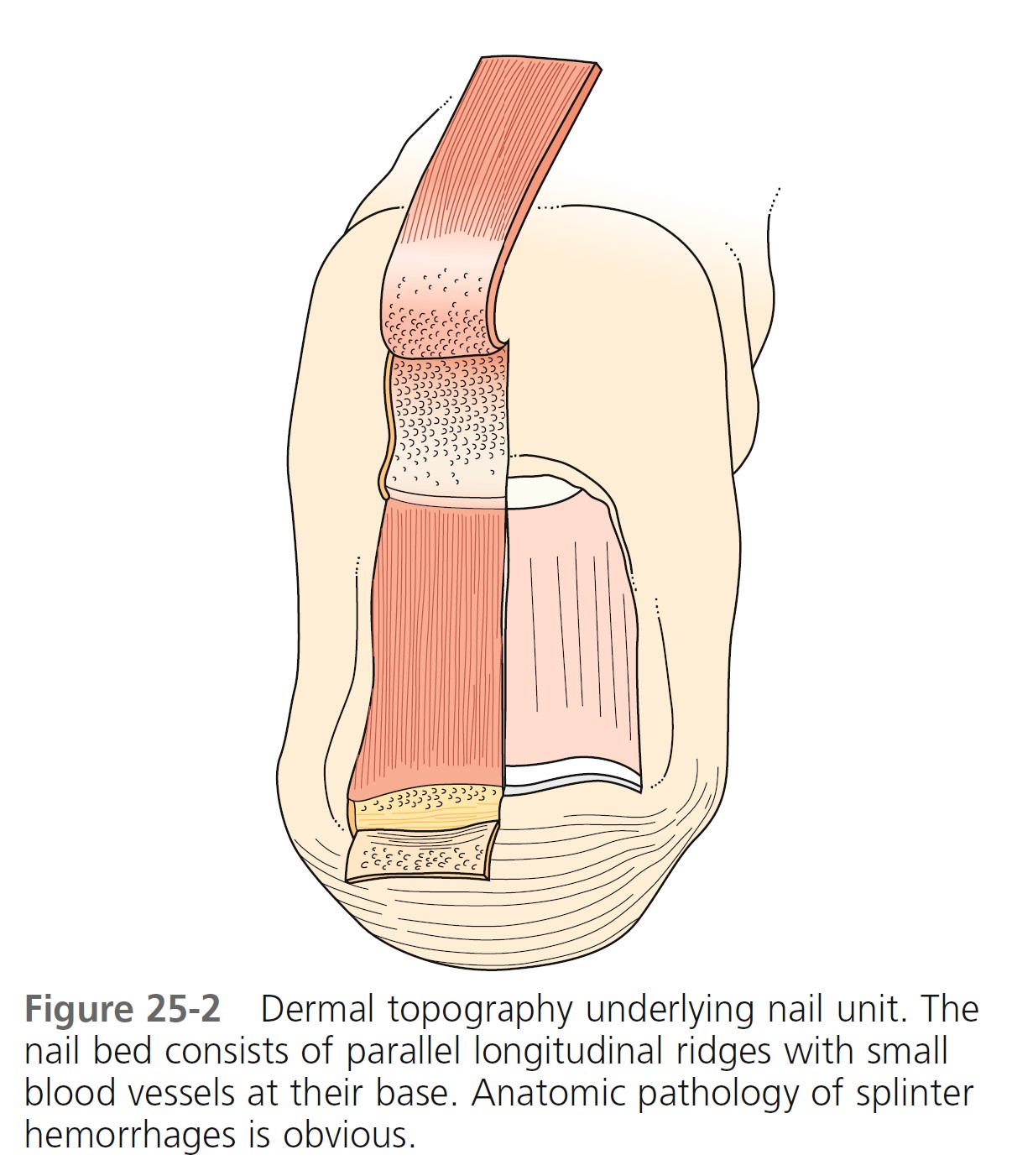

The matrix epithelium synthesizes 90% of the nail plate. The lunula (white half-moon), which is visible through the nail plate, is the distal aspect of the nail matrix. It is continuous with the nail bed. The nail bed extends from the distal nail matrix to the hyponychium. As the nail streams distally, material is added to the undersurface of the nail, thickening it and making it densely adherent to the nail bed. The nail bed consists of parallel longitudinal ridges with small blood vessels at their base ( Figure 25-2 ). Bleeding induced by trauma or vessel disease, such as lupus, occurs in the depths of these grooves, producing the splinter hemorrhage pattern viewed through the nail plate. The hyponychium is a short segment of skin lacking nail cover; it begins at the distal nail bed and terminates at the distal groove.

NAIL BIOPSY. Ungual biopsies are used to diagnose tumors, inflammatory disease, and infections. A punch or excisional biopsy technique is chosen, which provides a sufficient amount of tissue and produces a minimal amount of scarring. In practice these procedures are performed by some dermatologists and orthopedic hand surgeons. All of these techniques have recently been described. PMID: 1740326

GROWTH RATES. Nails grow continuously, but their growth rate decreases both with age and with poor circulation. Fingernails, which grow faster than toenails, grow at a rate of 0.5 to 2 mm per week. It takes approximately 5.5 months for a fingernail to grow from the matrix to the free edge and approximately 12 to 18 months for a toenail to be replaced. A reduction in the rate of matrix-cell division occurs during systemic diseases such as scarlet fever, causing thinning of the nail plate (Beau’s lines).

NORMAL VARIATIONS

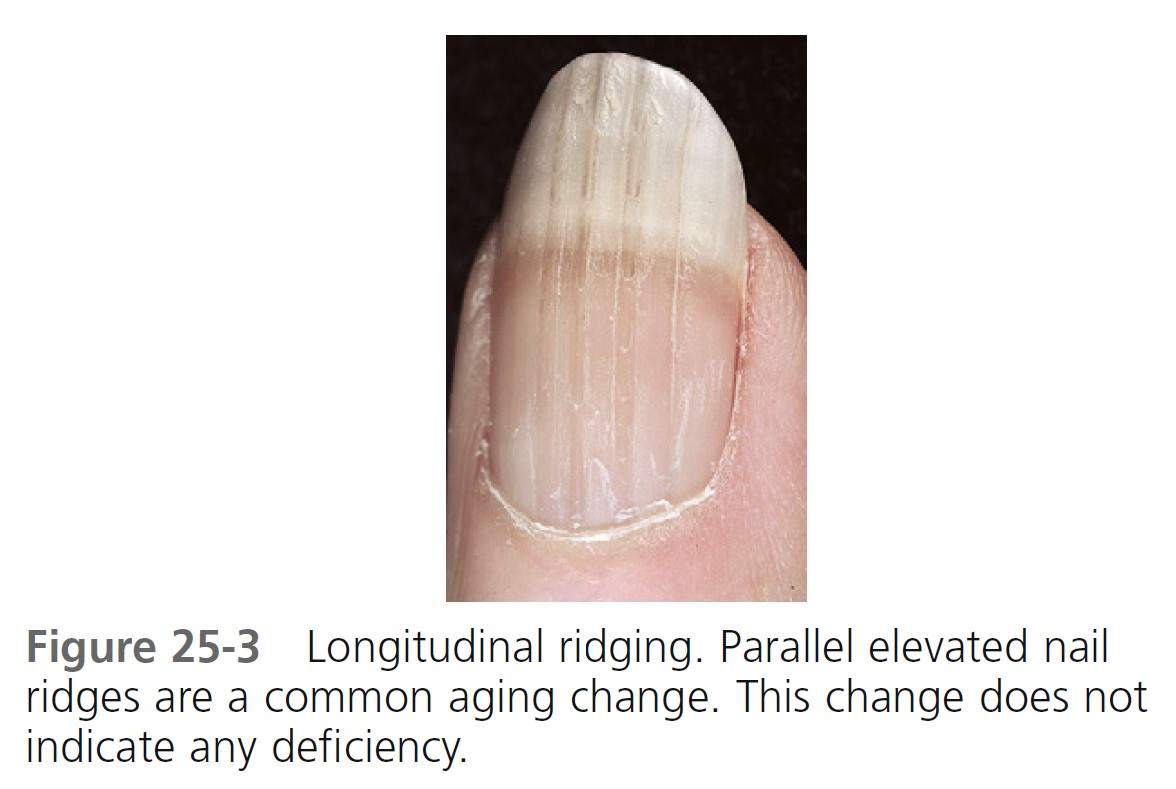

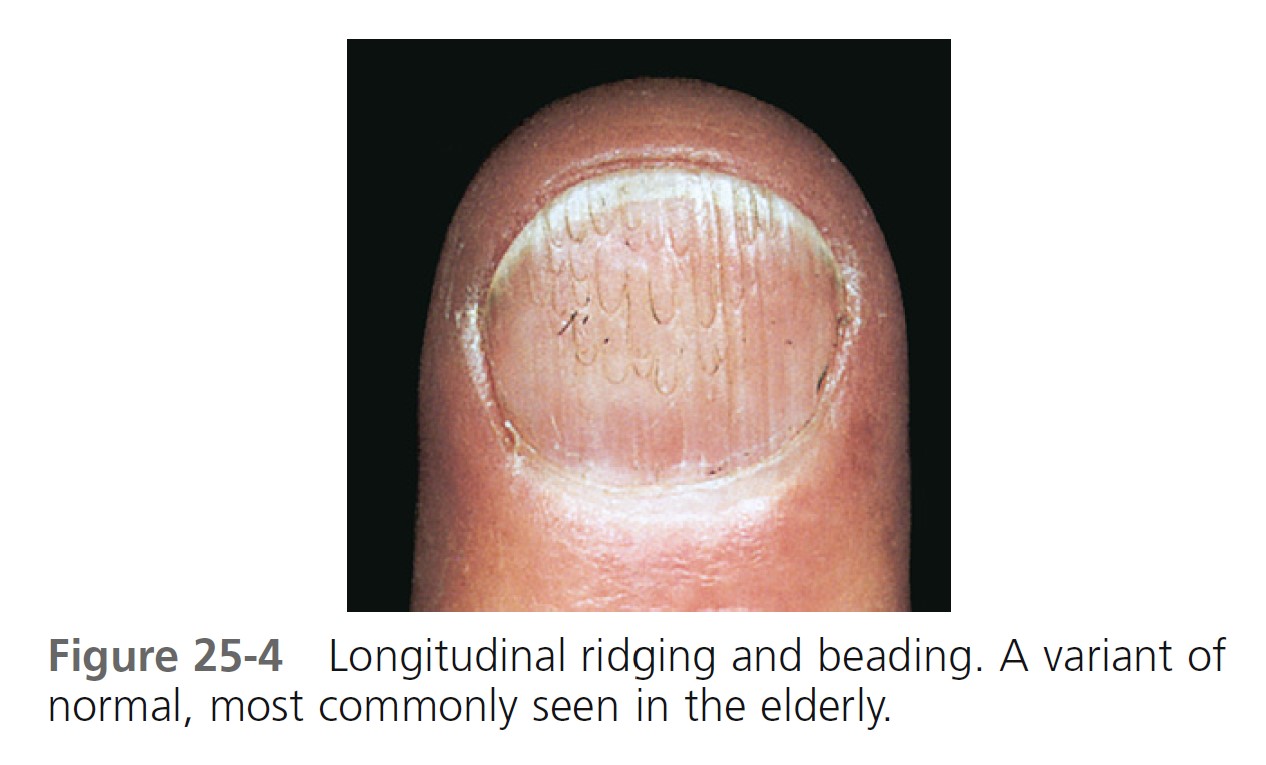

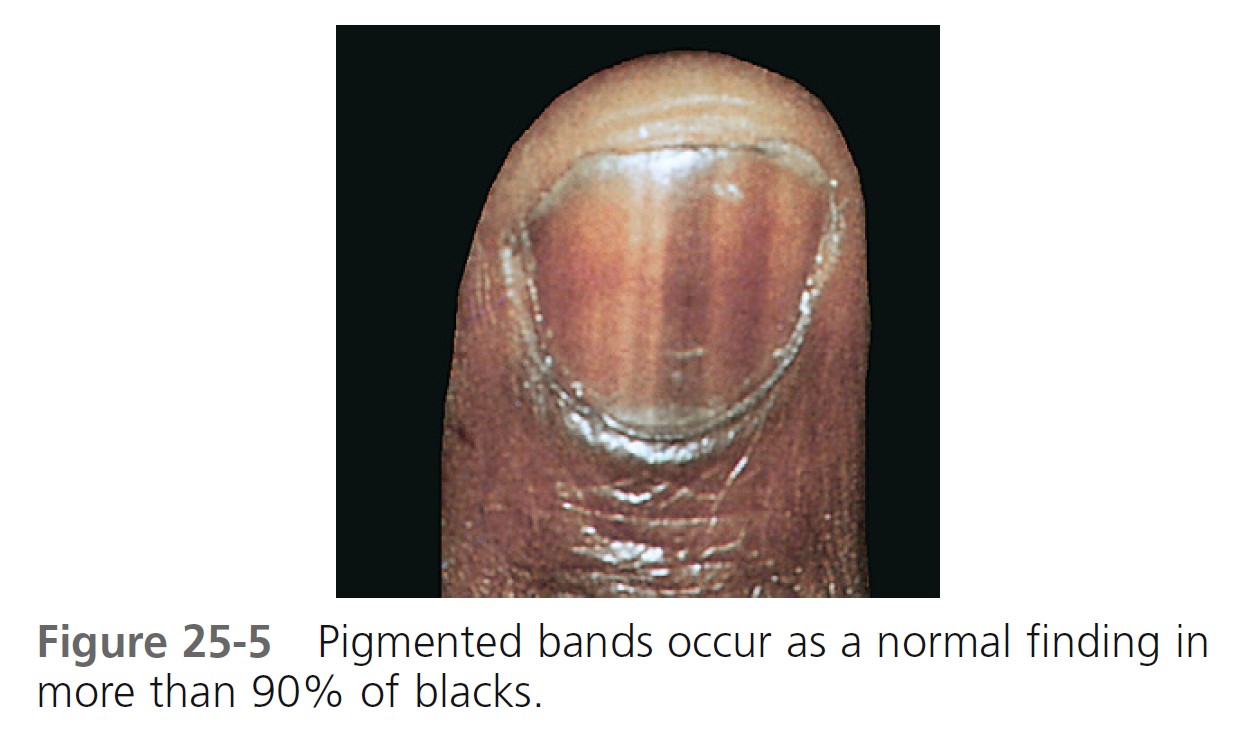

The shape and opacity of the nail vary considerably among individuals. Aging may increase or decrease nail thickness. Longitudinal ridging ( Figure 25-3 ) is common in aging, but this variant is occasionally observed among the young. Beading occurs at all ages but is more common in the elderly ( Figure 25-4 ). The beads cover part or most of the plate surface and are arranged longitudinally. A pigmented band or bands occur in more than 90% of blacks ( Figure 25-5 ). The sudden appearance of such a band in whites necessitates further investigation.

Nail structure can be altered by primary skin diseases, infections, trauma, internal diseases, congenital syndromes, and tumors. A more detailed discussion with illustrations of the most commonly encountered entities is presented in the following sections.

NAIL DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH SKIN DISEASE

PSORIASIS. Nail changes are characteristic of psoriasis (see p. 275 ), and the nails of psoriasis patients should be examined. These changes offer supporting evidence for the diagnosis of psoriasis when skin changes are equivocal or absent.

The incidence of nail involvement in psoriasis varies from 10% to 50%. Nail involvement usually occurs simultaneously with skin disease but may occur as an isolated finding. Over 50% of patients suffer from pain, and many are restricted in their daily activities.

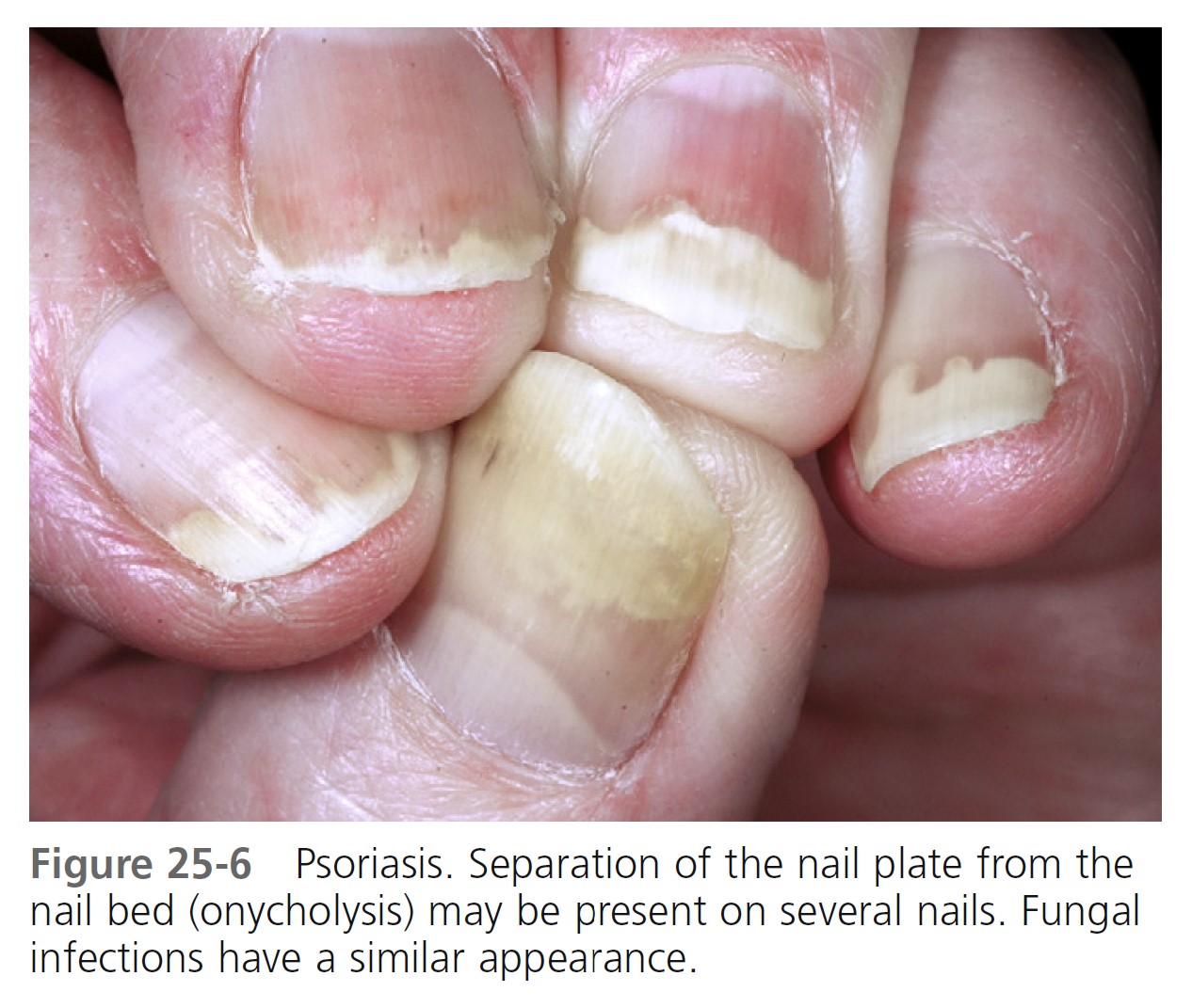

Onycholysis. Psoriasis of the hyponychium results in the accumulation of yellow, scaly debris that elevates the nail plate. The debris is commonly mistaken for nail fungus infection. Psoriasis of the nail bed causes separation of the nail from the nail bed. Unlike the uniform separation caused by pressure on the tips of long nails, the nail detaches in an irregular manner ( Figure 25-6 ). The nail plate turns yellow, simulating a fungal infection. Separation begins at the distal groove or under the nail plate and may involve several nails.

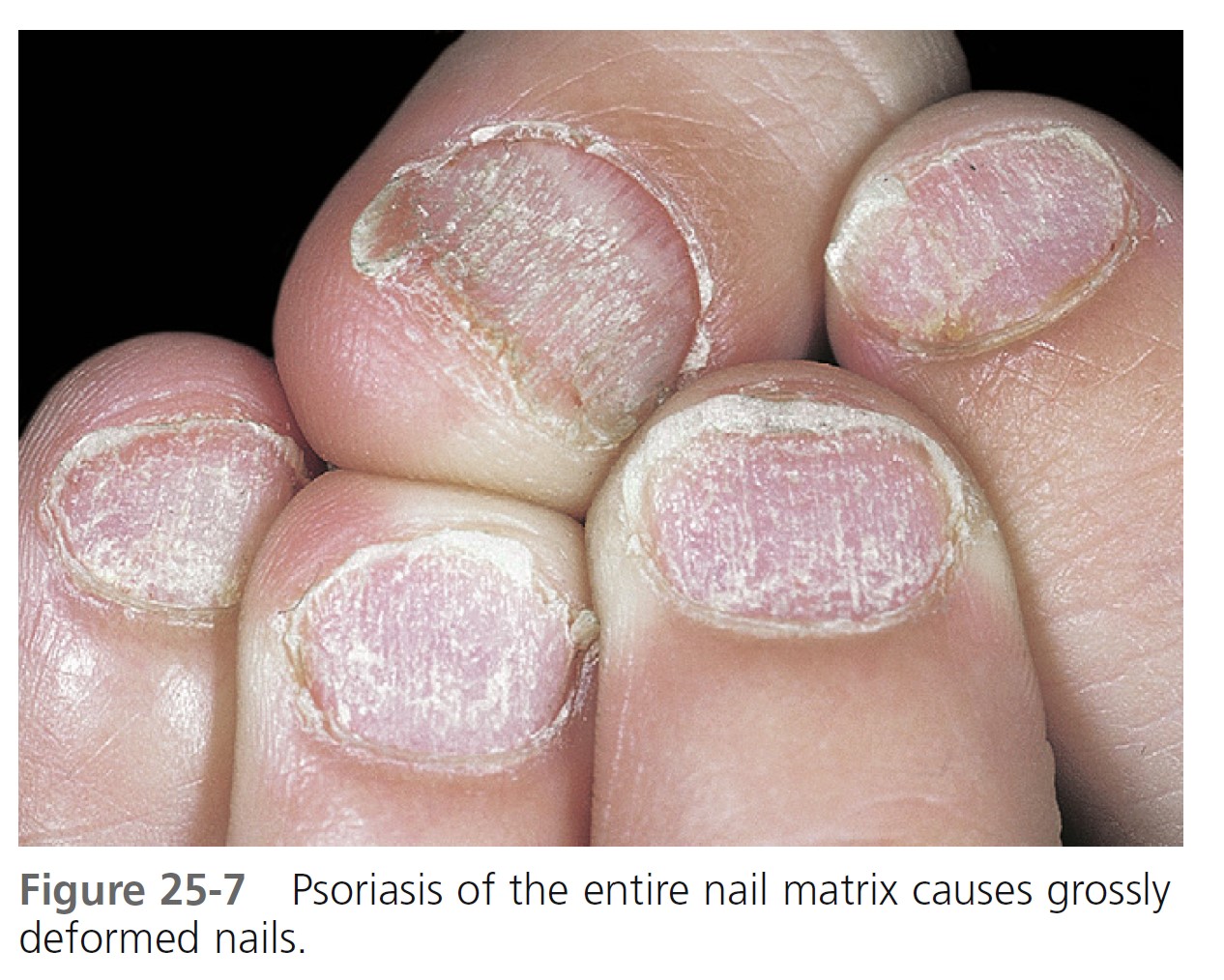

Nail deformity. Extensive involvement of the nail matrix results in a nail losing its structural integrity, resulting in fragmentation and crumbling. Gross alteration of the nail plate surface and nail bed splinter hemorrhages are common ( Figure 25-7 ).

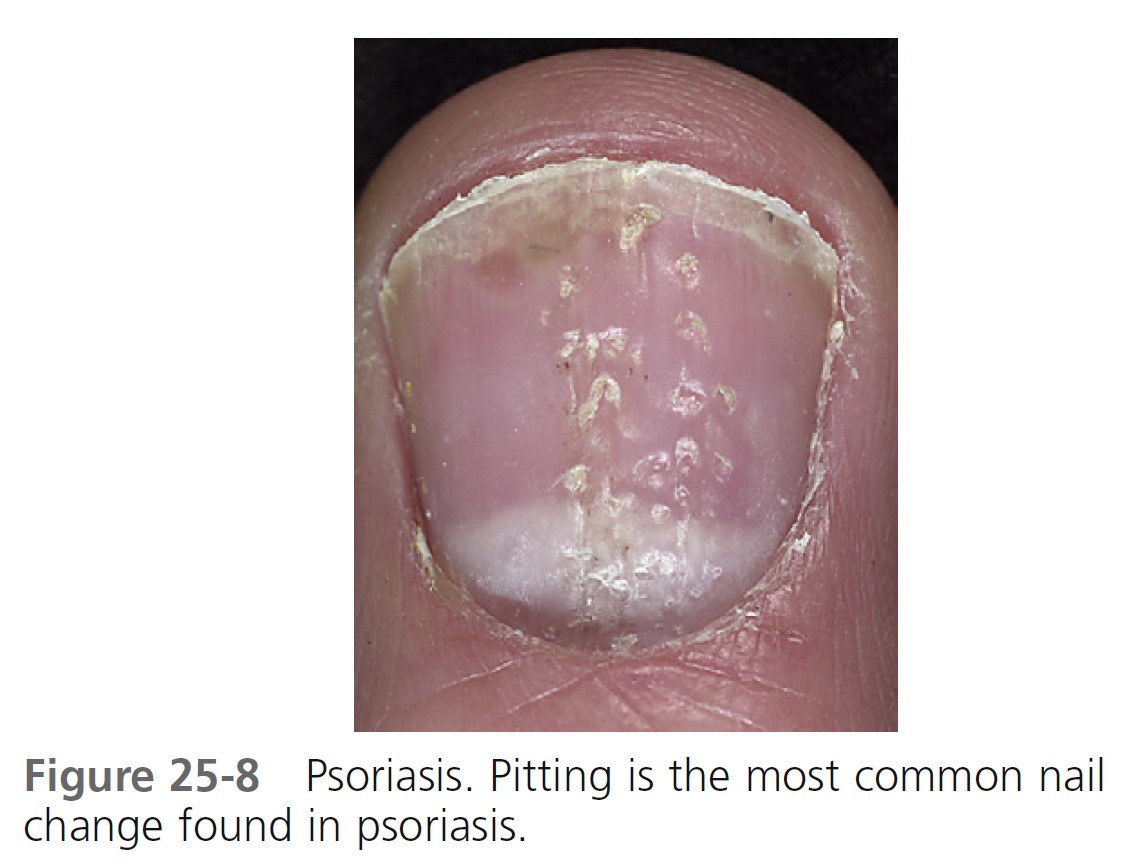

Pitting. Pitting, or sharply defined ice pick–like depressions in the nail plate, is the most common finding ( Figure 25-8 ). The number, distribution, patterns, and depth vary. Nail plate cells are shed in much the same way as psoriatic scale is shed, leaving a variable number of tiny, punched out depressions on the nail plate surface. They emerge from under the cuticle and grow out with the nail. Many other cutaneous diseases may cause pitting (e.g., eczema, fungal infections, and alopecia areata), or it may occur as an isolated finding in a normal variation.

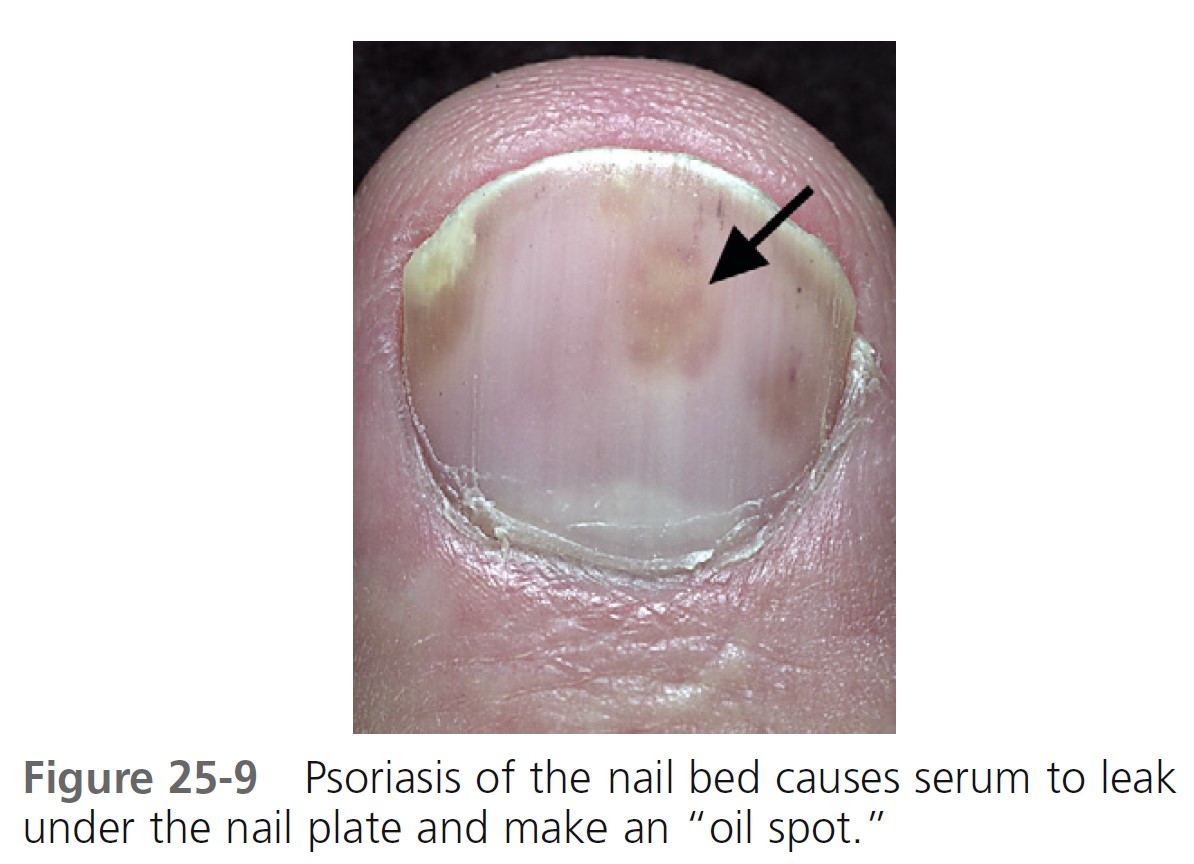

Oil spot lesion. Psoriasis of the nail bed may cause localized separation of the nail plate. Cellular debris and serum accumulate in this space. The brownish-yellow color ( Figure 25-9 ) observed through the nail plate looks like a spot of oil.

TREATMENT

Nail psoriasis is difficult to treat, but may respond to different approaches used alone or together. PMID: 17572277 Relapse is common. Nails may improve when patients are treated with systemic agents such as cyclosporine, methotrexate, acitretin, or biologic agents.

TRIAMCINOLONE ACETONIDE. Intralesional injection at monthly intervals into the matrix with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) (2.5 to 10 mg/ml) delivered with a 30-gauge needle is the standard treatment for psoriatic nail disease used by most dermatologists. A simplified protocol has been proposed. Triamcinolone acetonide (0.4 ml, 10 mg/ml) is injected, following ring block, at each of four periungual sites: two at the nail matrix and one in each lateral nailfold, directed medially towards the nail bed. This method is utilized to achieve delivery of the agent to both the nail matrix and the nail bed. If needed, a second set of injections is administered after 2 months. Subungual hyperkeratosis, ridging, and thickening respond well. Benefits are sustained for at least 9 months. Onycholysis and pitting are less responsive.

CALCIPOTRIOL. Calcipotriol cream or ointment once daily every weeknight and clobetasol once daily every weekend for 6 months followed by clobetasol twice weekly for the second 6 months reduce subungual hyperkeratosis. Calcipotriol ointment twice daily for up to 5 months is less effective. Calcipotriene 0.005% and betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% ointment (Taclonex ointment, Dovobet ointment) is a combination that may be effective with once-daily application to nails and nailfolds.

TAZAROTENE. Tazarotene 0.1% gel (Tazorac) is applied each evening for up to 24 weeks to fingernails. Medication can be used under occlusion or unoccluded. Tazarotene gel reduced onycholysis (in occluded and nonoccluded nails) and pitting (in occluded nails).

BIOLOGIC DRUGS. Case reports show rapid improvement of psoriatic nails with etanercept and infliximab. There is little merit in treating psoriatic nails with photochemotherapy (PUVA) or topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU).

PUSTULAR PSORIASIS OF THE NAIL APPARATUS

Pustular psoriasis of the nail bed, matrix, or surrounding skin is common and may be painful. It has a chronic course and poor response to treatment. Severe cases are treated with systemic retinoids. Topical calcipotriol is effective in about 50% of patients with localized disorder and is also useful as maintenance therapy after retinoid treatment. Calcipotriene 0.005% and betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% ointment (Taclonex ointment, Dovobet ointment) is a combination that may be more effective than calcipotriene alone.

LICHEN PLANUS

Approximately 25% of patients with nail lichen planus (LP) have LP in other sites before or after the onset of nail lesions. Nail LP usually appears during the fifth or sixth decade of life. The matrix, nail bed, and nailfolds may be involved in producing a variety of changes, few of which are characteristic. Minimal inflammation of the matrix induces longitudinal grooving and ridging, which are the most common findings of LP of the nail. The development of severe and early destruction of the nail matrix with scarring characterizes a small subset of patients with nail LP. A pterygium, caused by adhesion of a depressed proximal nailfold to the scarred matrix, may occur after intense matrix inflammation ( Figure 25-10 ). The nail plate distal to this focus is either absent or thinned out. In most cases, nail LP is self-limiting or promptly regresses with treatment. Permanent damage to the nail is uncommon, even in patients with diffuse involvement of the matrix. Matrix lesions may respond to intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (2.5 to 5 mg/ml) delivered with a 30-gauge needle every 3 or 4 weeks. Severe cases respond to prednisone (20 to 40 mg/day). This may require a long course of treatment in which the possible risks may outnumber the advantages. Onychomycosis may be confused clinically with lichen planus.

ACQUIRED DISORDERS

Bacterial and viral infections

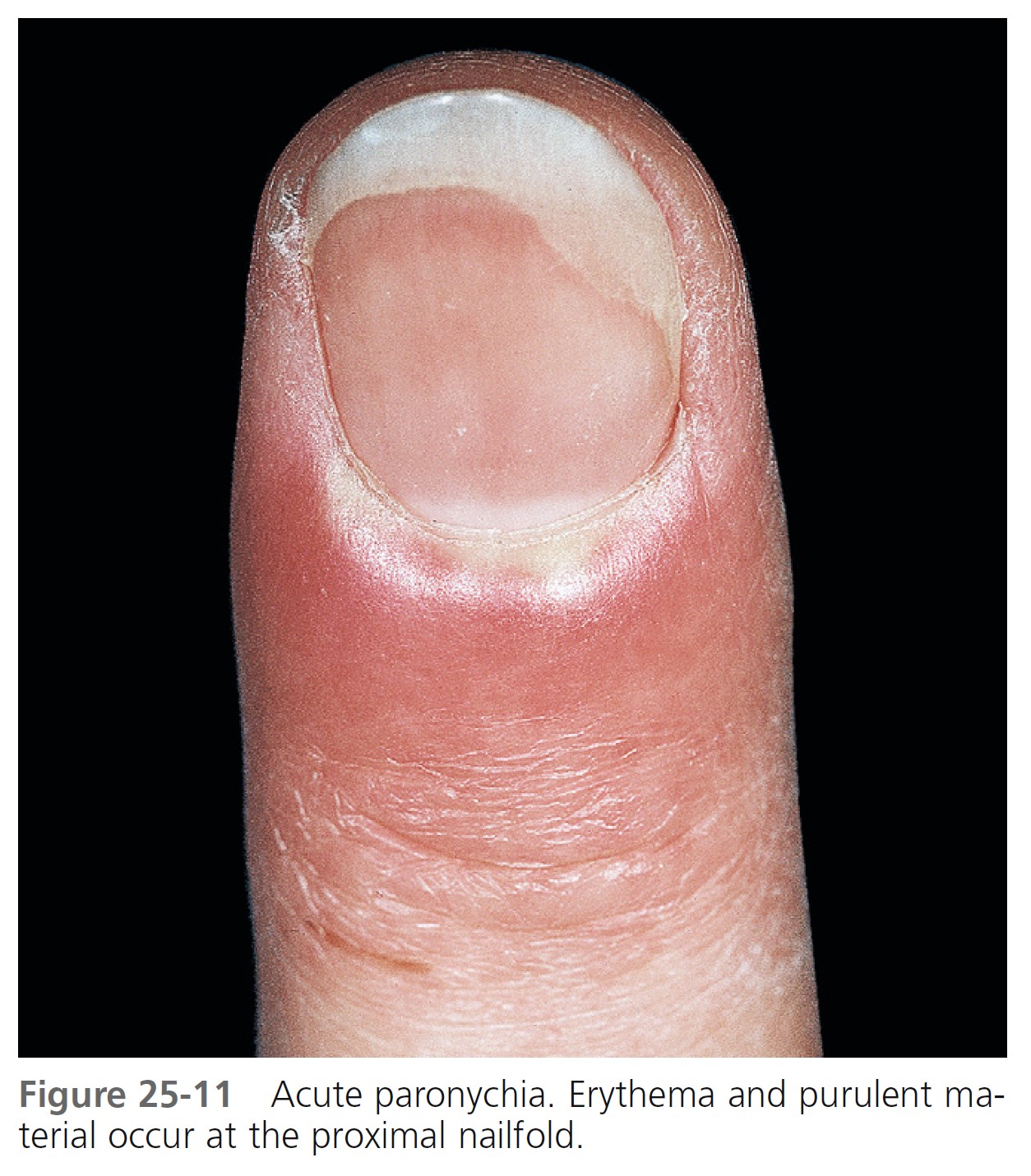

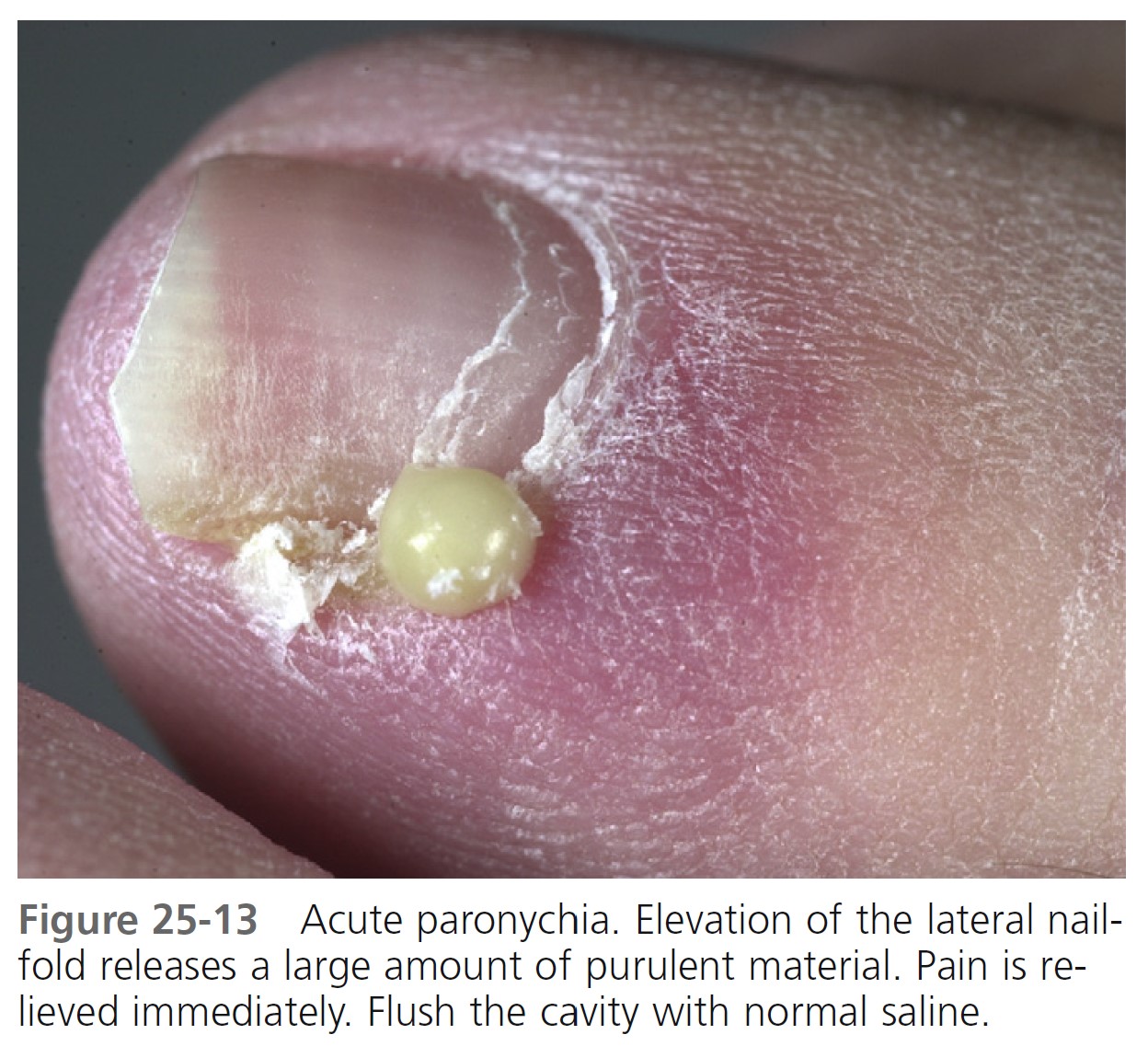

ACUTE PARONYCHIA. The rapid onset of painful, bright red swelling of the proximal and lateral nailfold may occur spontaneously or may follow trauma or manipulation ( Figures 25-11 and 25-12 ). Superficial infections present with an accumulation of purulent material behind the cuticle (see Figure 25-12 ). The small abscess is drained by inserting a 23- or 21-gauge needle tip or similar instrument between the proximal nailfold and the nail plate and lifting the nailfold with the tip of the needle (see Figure 25-13 ). Pain is abruptly relieved as the purulent material drains. There is no need for anesthesia or daily dressing. A diffuse, painful swelling suggests deeper infection, and cases that do not respond to antistaphylococcal antibiotics may require deep incision. Acute paronychia rarely evolves into chronic paronychia.

Treatment. Treatment of acute paronychia is determined by the degree of inflammation. If an abscess has not formed, the use of warm water compresses may be effective. The combination of a topical antibiotic (mupirocin or bacitracin/neomycin/polymyxin B) and a group II or III corticosteroid such as betamethasone dipropionate cream is safe and effective for treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial paronychia and seems to offer advantages compared with topical antibiotics alone. Persistent lesions are treated with oral antistaphylococcal antibiotics and/or deep surgical drainage.

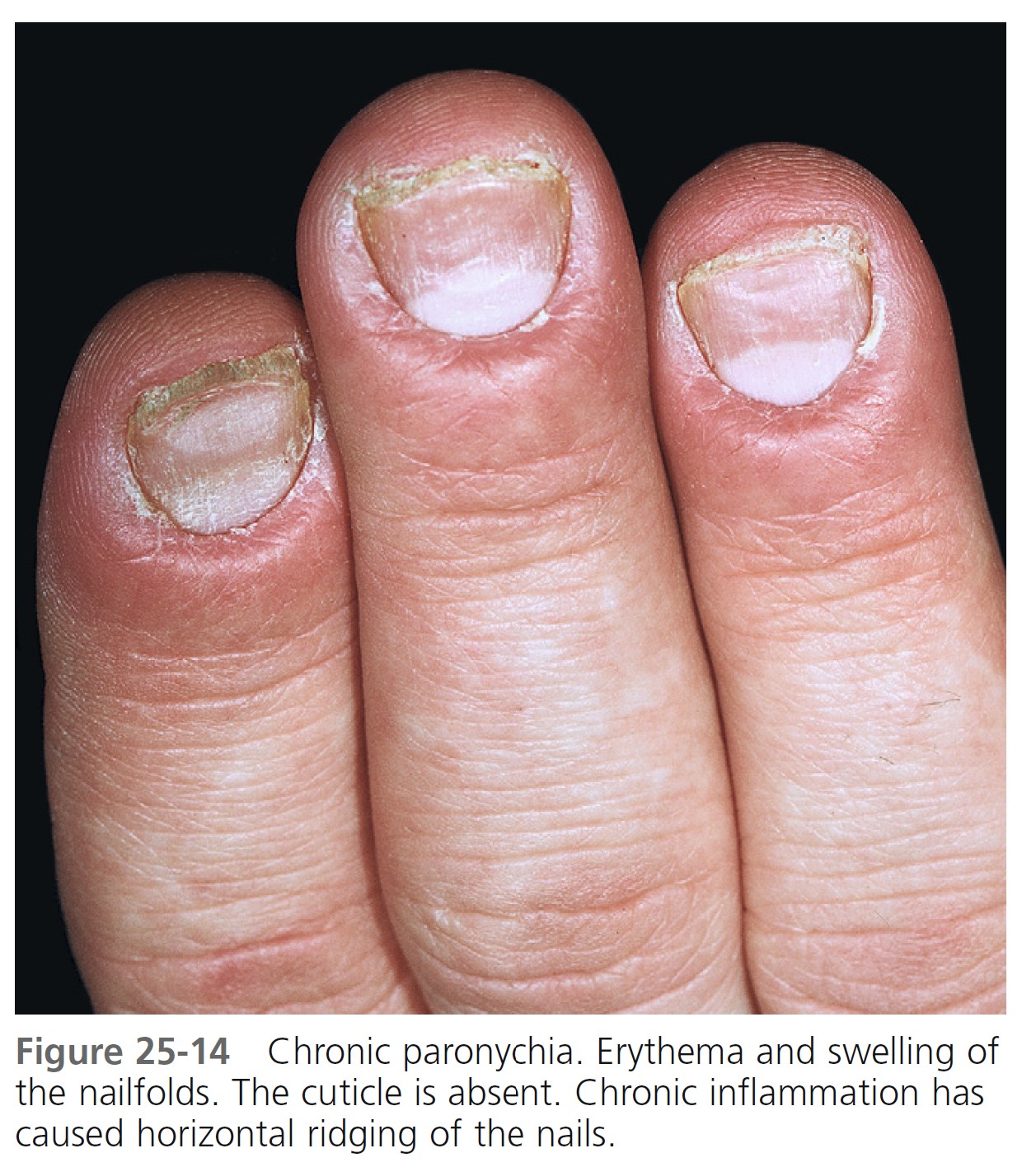

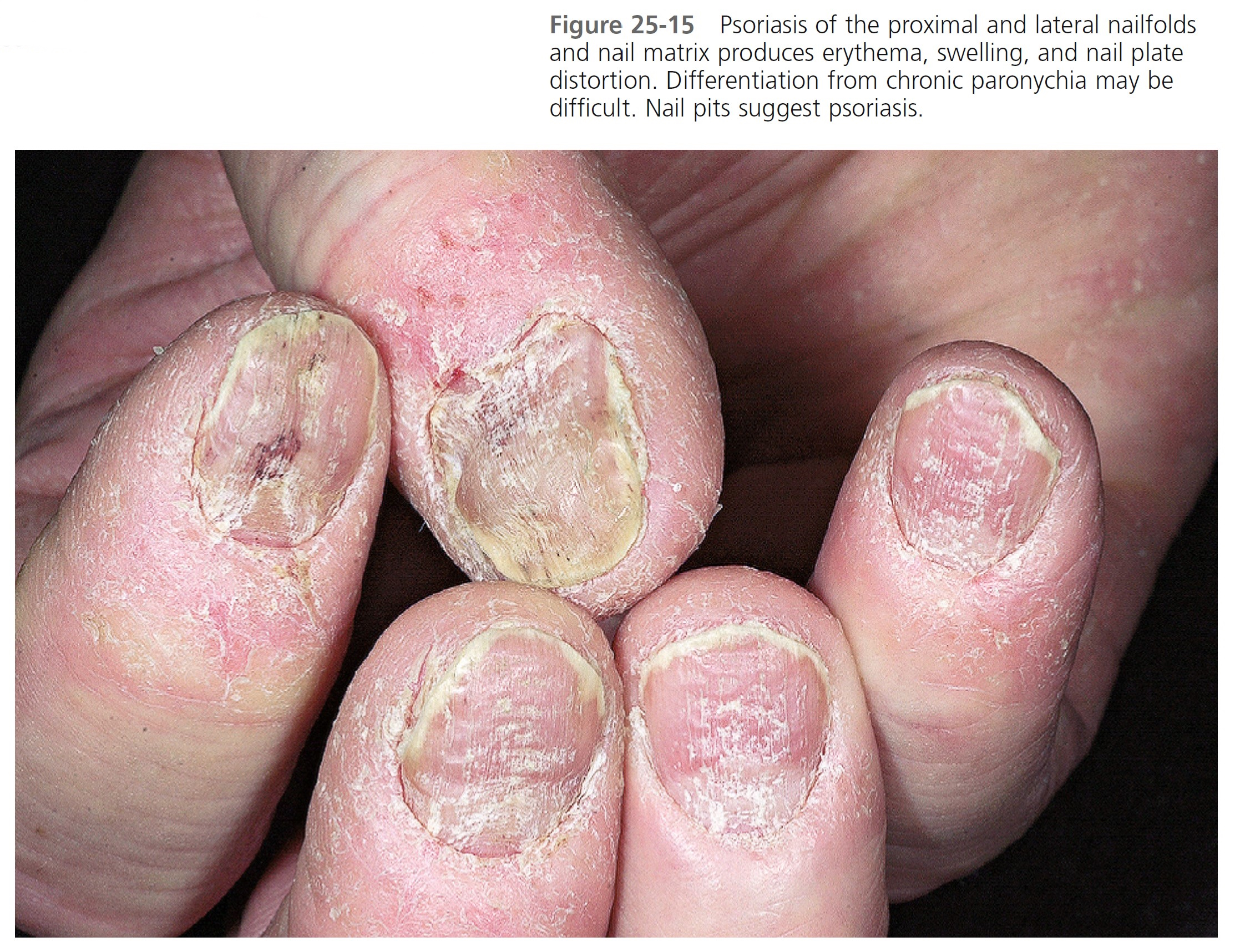

CHRONIC PARONYCHIA. Chronic paronychia is not a yeast infection, but rather an inflammation of the proximal and lateral nailfolds. Chronic paronychia evolves slowly and presents initially with tenderness and mild swelling about the proximal and lateral nailfolds ( Figure 25-14 ). Significant contact irritant exposure is a major cause. Individuals whose hands are repeatedly exposed to moisture (e.g., bakers, dishwashers, and dentists) are at greatest risk. Manipulation of the cuticle accelerates the process. Typically, many or all fingers are involved simultaneously. The cuticle separates from the nail plate, leaving the space between the proximal nailfold and the nail plate exposed to infection. Many organisms, both pathogens and contaminants, thrive in this warm, moist intertriginous space. The skin about the nail becomes pale red, tender or painful, and swollen. Occasionally a small quantity of pus can be expressed from under the proximal nailfold. A culture of this material may grow Candida or gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. Candida is probably just a colonizer of the proximal nailfold rather than a direct cause of the disease. It disappears when the physiologic barrier is restored. The nail plate is not infected and maintains its integrity, although its surface becomes brown and rippled. There is no subungual thickening such as that present in some fungal infections. Proximal separation of the nail plate from the matrix area may occur as a consequence of nail matrix damage. The nail plate may sometimes present a green discoloration of its lateral margins as a result of Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization. The process is chronic and responds very slowly to treatment. Psoriasis of the fingers may present in a similar form ( Figure 25-15 ).

Treatment. Resolution of chronic paronychia depends on avoiding exposure to contact irritants and on treatment of underlying inflammation and infection. Every attempt must be made to keep the proximal nailfold dry. Patients should refrain from washing dishes and from washing their own hair. Rubber or plastic gloves are of some value, but moisture accumulates in them with prolonged use. The hands stay dry if a cotton glove is worn under the rubber glove. Controlling inflammation is the primary goal. Topical steroid creams (group V) applied twice daily for up to 3 weeks are more effective than systemic antifungals. Oral antibiotics do not penetrate this distal site in sufficient concentration, and the variety of organisms is too numerous to respond to a single oral agent. Treatments to keep the space between the nail plate and proximal nailfold may help. Place fungoid tincture (miconazole), ciclopirox (olamine) topical suspension or one or two drops of 3% thymol in 70% ethanol (compounded by a pharmacist) at the proximal nailfold and wait for this liquid to flow by capillary action into the space created by the absent cuticle. Slight elevation of the proximal nailfold with a flat toothpick facilitates penetration. This should be repeated two or three times a day for weeks, until the cuticle is re-formed. The cuticle may never re-form in patients with long-standing inflammation. Fluconazole (200 mg/day) for 1 to 4 weeks may control chronic inflammation. Short courses of fluconazole may have to be repeated as the infection recurs.

DRUG-INDUCED PARONYCHIA. The protease inhibitors lamivudine and indinavir, used to treat human immunodeficiency virus, have been reported to cause paronychia and ingrown toenails in about 4% of patients receiving these drugs. Pyogenic granuloma–like lesions, staphylococcal superinfection, onycholysis, and severe skin dryness may also be present. The nails of the great toes are usually affected. The lesions appear 2 to 12 months after starting treatment. Complete regression of skin manifestations occurs within 9 to 12 weeks after the drugs are withdrawn. Inhibition of endogenous proteases may explain the initial hypertrophy of the nailfold and the subsequent development of pyogenic granuloma–like lesions.

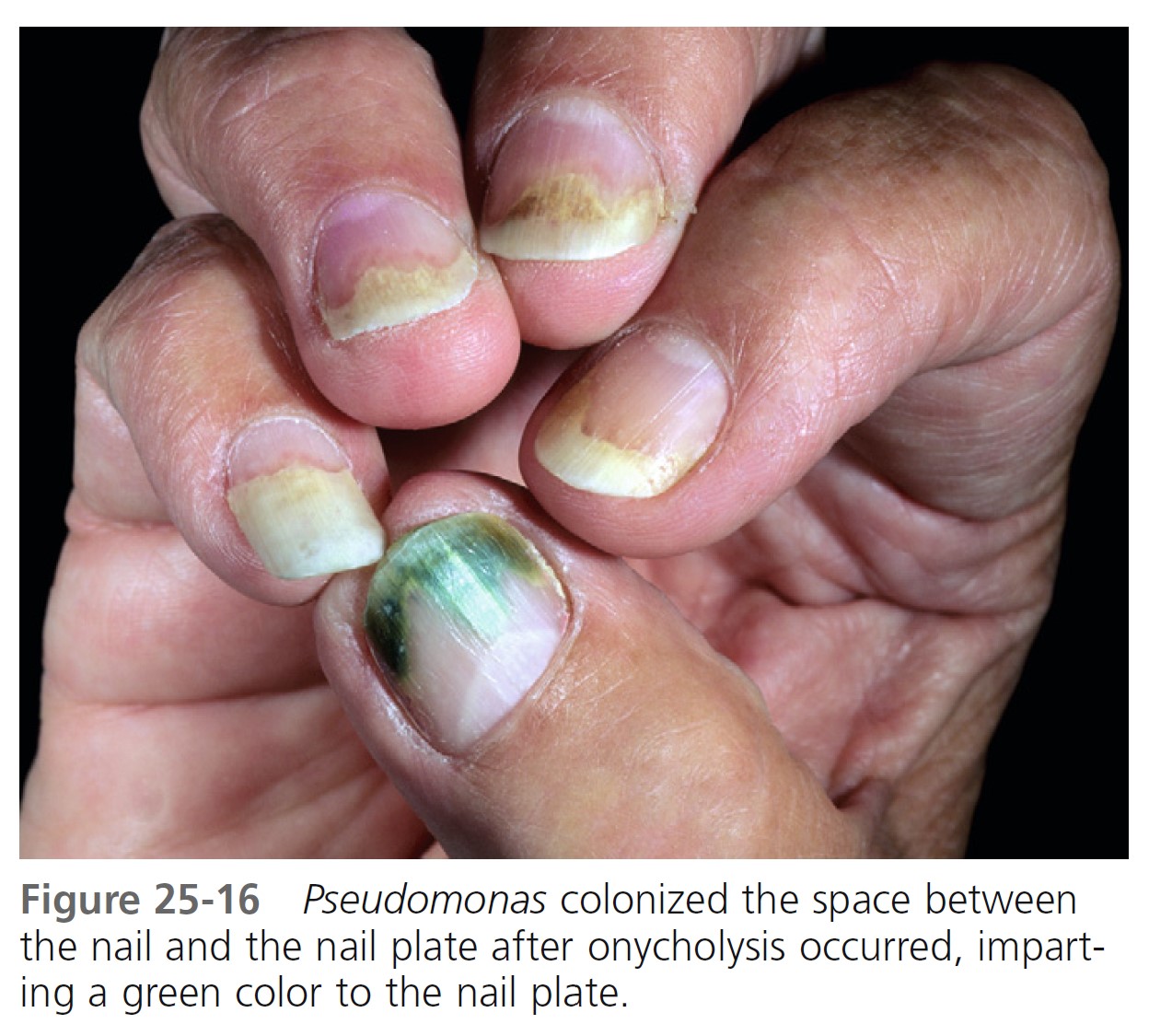

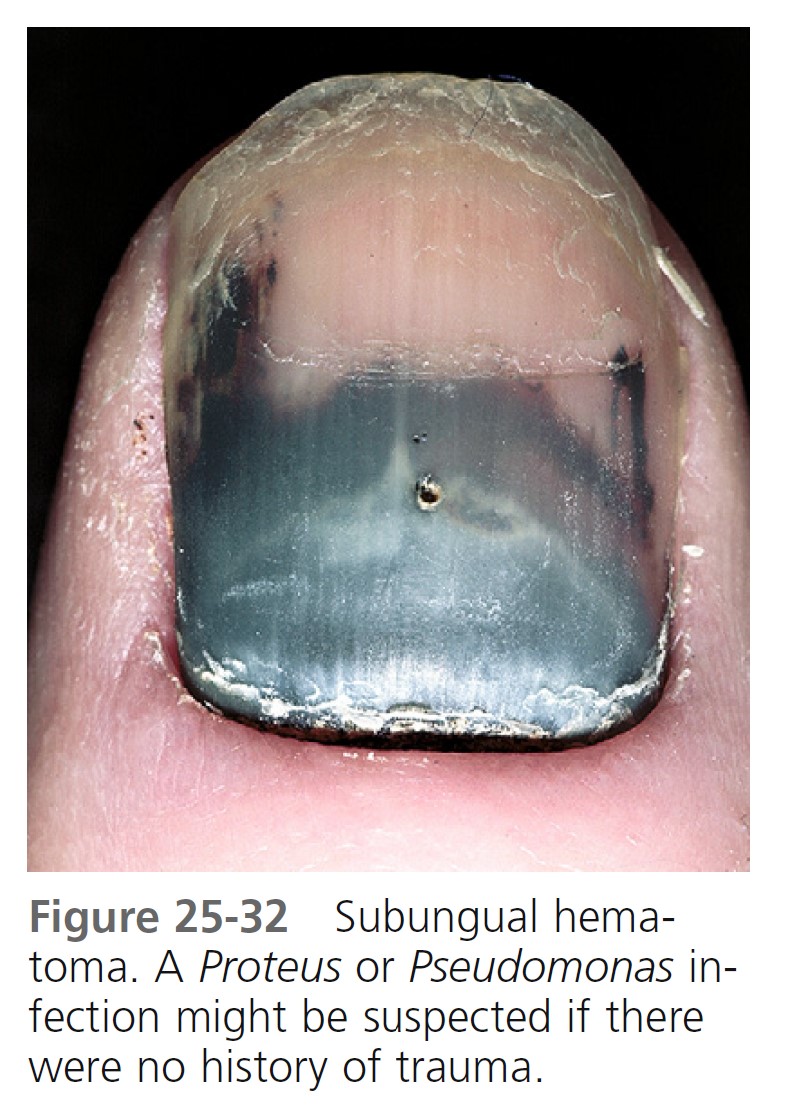

PSEUDOMONAS INFECTION. Repeated exposure to soap and water causes maceration of the hyponychium and softening of the nail plate. Separation of the nail plate (onycholysis) exposes a damp, macerated space between the nail plate and the nail bed, which is a fertile site for the growth of Pseudomonas . The nail plate assumes a greenblack color ( Figure 25-16 ). There is little discomfort or inflammation. This presentation may be confused with subungual hematoma (see Figure 25-32 ), but the absence of pain with Pseudomonas infection establishes the diagnosis. Apply a few drops of a mixture of one part chlorine bleach/four parts water under the nail three times a day. Vinegar (acetic acid) may also be used.

HERPETIC WHITLOW. In the past, dentists and nurses were at risk of acquiring herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection of the fingertip. Young adults are typically affected by HSV-2. HSV-1 infection of the hand occurs in children as a result of autoinoculation following herpetic gingivostomatitis. The risk has greatly diminished with the use of gloves. The appearance and course of the disease resemble those at other body sites, except that there is extreme pain from the swollen fingertips ( Figure 25-17 ). Lymphangitis and lymphadenitis, secondary to HSV infection of the hand, are possible complications, particularly with HSV-2 infection. Herpes simplex virus infection in AIDS patients is characterized by atypical presentations and unusual locations. Herpetic finger infections in these patients may rapidly progress to the complete destruction of nail structures.

Fungal nail infections

Tinea of the nails is also called tinea unguium. Dermatophytes Trichophyton rubrum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes are responsible for most fingernail and toenail infections. Certain nondermatophyte nail pathogens (e.g., cytalidium dimidiatum and Scytalidium hyalinum ) may also cause infection. Other nondermatophyte nail pathogens (certain species of Acremonium, Alternaria, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Onychocola, and Scopulariopsis ) may cause infection. Candida albicans can occasionally be a pathogen in fingernail disease. Multiple pathogens may be present in a single nail. Nail infection may occur simultaneously with hand or foot tinea or may occur as an isolated phenomenon. Onychomycosis is estimated to affect approximately 2% to 13% of the population of North America and Europe. The disease may also occur in children. Trauma predisposes to infection. There is a tendency to label any process involving the nail plate as a fungal infection, but many other cutaneous diseases can change the structure of the nail. Fifty percent of thick nails are not infected with fungus. Many patients with nail disease have psoriasis and are not infected with fungus. Differential diagnosis is discussed at the end of this section.

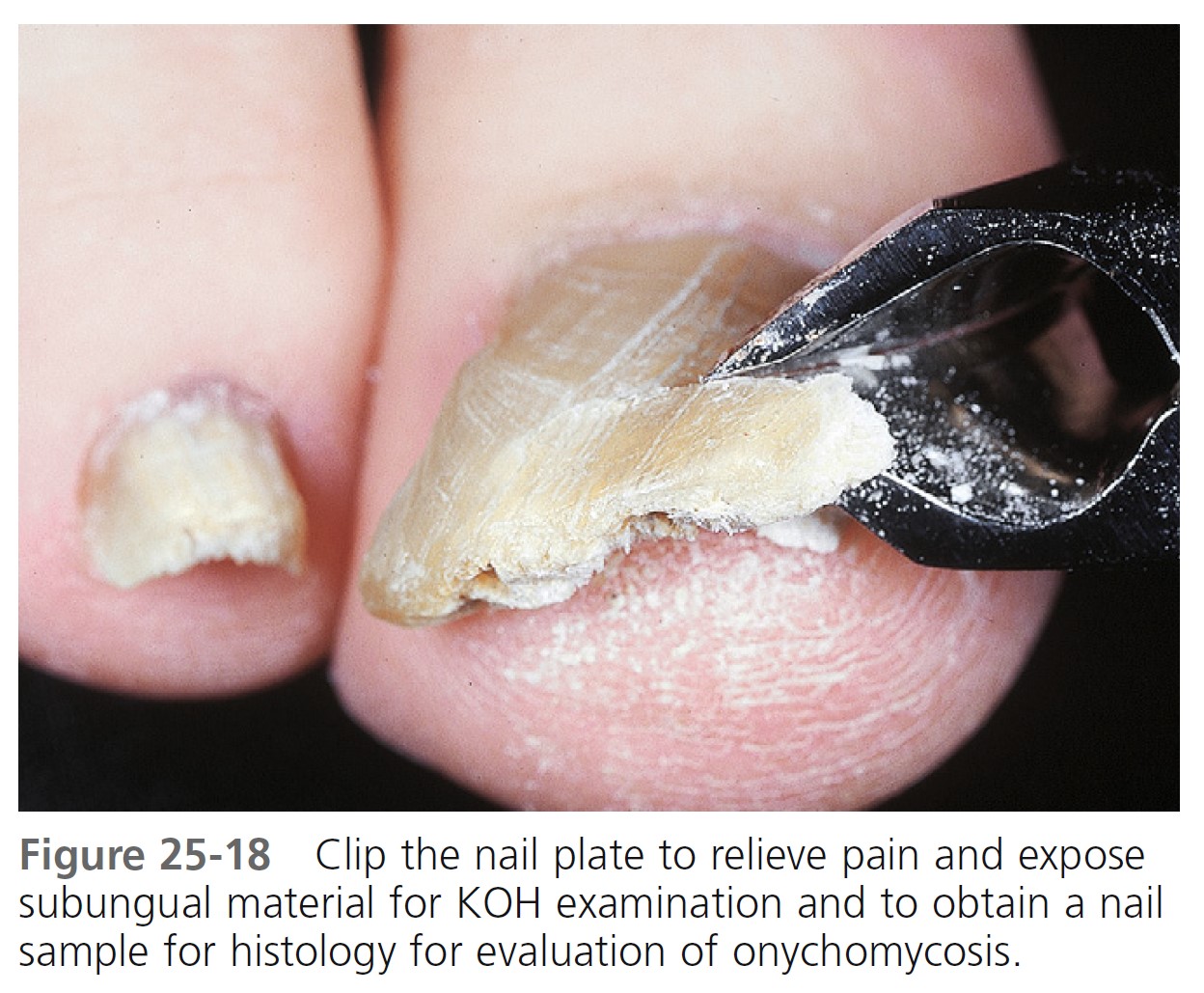

TINEA VS. PSORIASIS. Differentiation of fungal infection from dystrophic changes resulting from psoriasis or other causes is difficult. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations, culture, and, occasionally, nail unit biopsy specimens are used. These tests are time-consuming and may yield false-negative results. Histologic examination of distal nail clipping specimens by routine histology and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining is an accurate and simple method for differentiating onychomycosis from nail psoriasis ( Figure 25-18 ). It is equal to culture and superior to KOH preparation in leading to the correct diagnosis of dermatophyte infection.

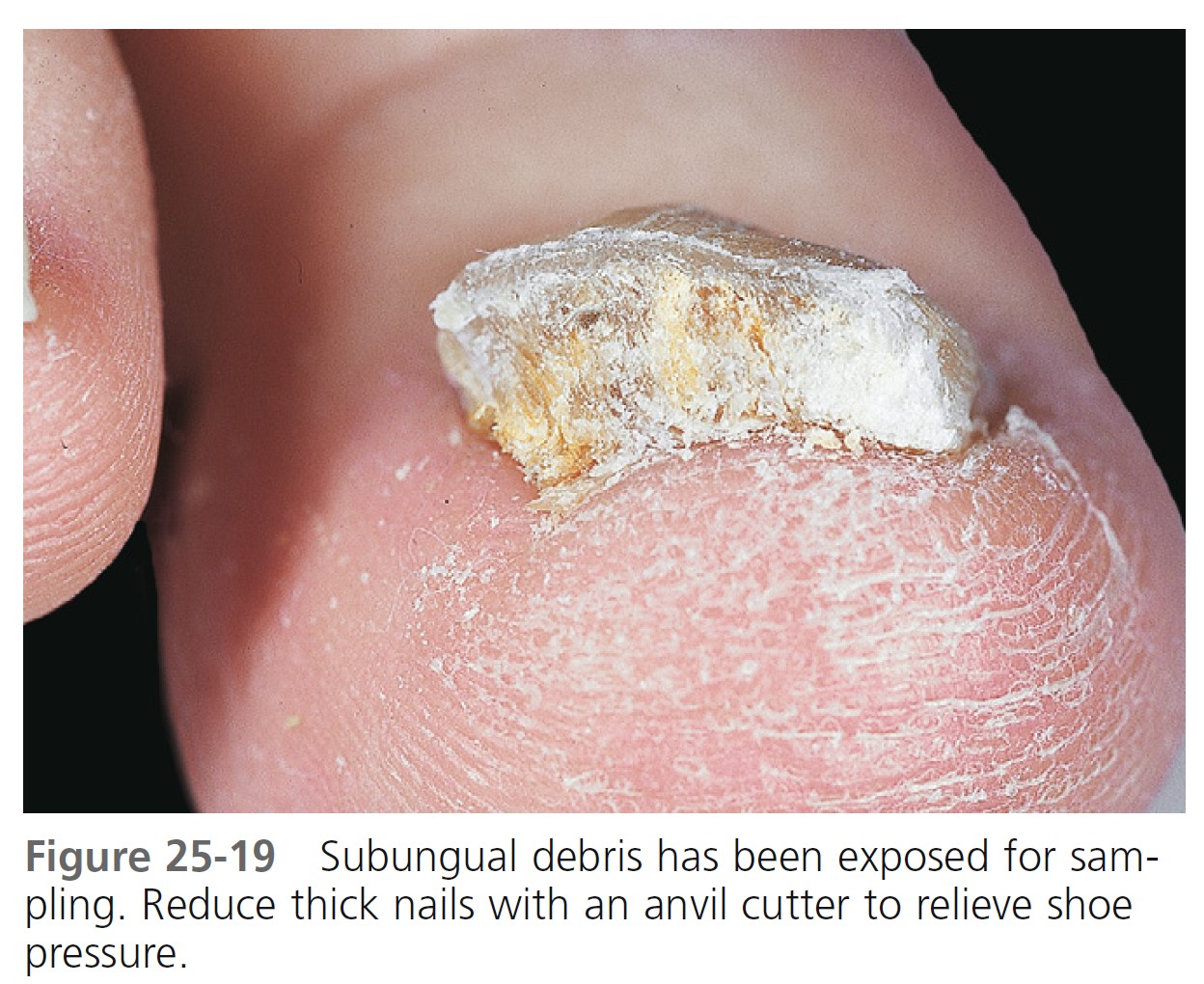

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS. The diagnosis of fungal nail infection may be established with both a potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination and a culture, and occasionally a nail biopsy. Physicians without the facilities to perform a KOH or culture may obtain these services from local or specialty laboratories, such as the University Center for Medical Mycology, Department of Dermatology, www.medicalmycology.org . These specialty laboratories provide convenient containers for specimen collection. Mayo Medical Laboratories provides a similar service ( www.mayomedicallaboratories.com ). Confirm the species of fungus before starting oral antifungal treatment. When performing cultures, obtain crumbling debris from under several nails and at different parts (proximal and distal areas of infection) of the infected nail ( Figure 25-19 ). Collect subungual debris from under the distal edge of the nail with a curette. Sample the nail surface with a curette or scrape it with a #15 scalpel blade ( Figure 25-20 ). Fungi are found in the nail plate and in the cornified cells of the nail bed. Hyphae that are present in the nail plate may not be viable; therefore sample the cornified cells of the nail bed if possible.

Nail biopsy. Many clinicians initiate therapy after confirming the presence of hyphae in a nail biopsy specimen. The potassium hydroxide test is the most cost-effective diagnostic method but a nail biopsy using nail clipping for histology is more sensitive. Submit the nail clipping in the same formalin solution used for skin biopsies. The laboratory will stain sections of the nail with periodic acid-Schiff, which stains fungal hyphae. The fungal species cannot be identified with this method.

Nail collection techniques for culture. First swab the nail plate with alcohol to remove bacteria. Fragments of nail plate and nail bed scrapings are inoculated onto Sabouraud’s medium with and without antibiotics to identify the fungal species. Use fresh Sabouraud’s with antibiotics. Antibiotics degrade in old media and do not effectively suppress bacterial contaminants. The dermatophyte test medium contains the antibiotic cycloheximide and phenol red as a pH indicator. Dermatophytes release alkaline metabolites that turn the medium from yellow to red in 7 to 14 days. Some nondermatophytes, such as Scopulariopsis, Aspergillus, Penicillium, black molds, and yeast, may cause a color change and give a false-positive reaction. The nail plate and hard debris can be adequately softened for direct examination by leaving the fragments, along with several drops of potassium hydroxide, in a watch glass covered with a Petri dish for 24 hours. (See Chapter 13 on fungal infections for details of the KOH examination.)

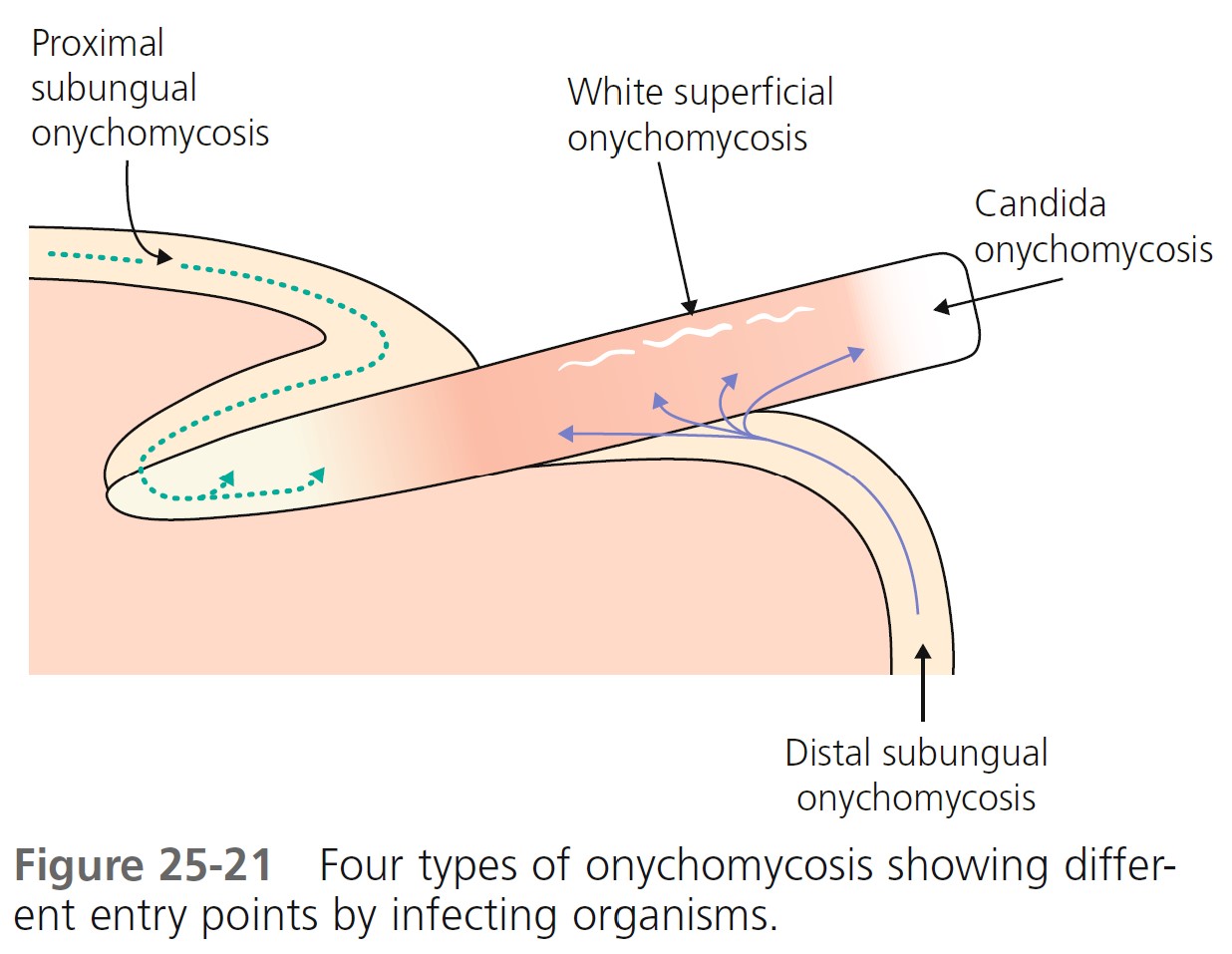

PATTERNS OF INFECTION. There are four distinct patterns of nail infection. Several patterns of infection may occur simultaneously in the nail plate. T. rubrum and T. mentagrophytes invade the nail plate more frequently than T. violaceum or T. tonsurans . Aspergillus, Cephalosporium, Fusarium, and Scopulariopsis, generally considered contaminants or nonpathogens, have been isolated from infected nails. They may be found in any pattern of nail infection, especially distal subungual onychomycosis and white superficial onychomycosis. The contaminants do not respond to griseofulvin or the newer oral antifungal agents. The four patterns of nail infection are illustrated in Figure 25-21.

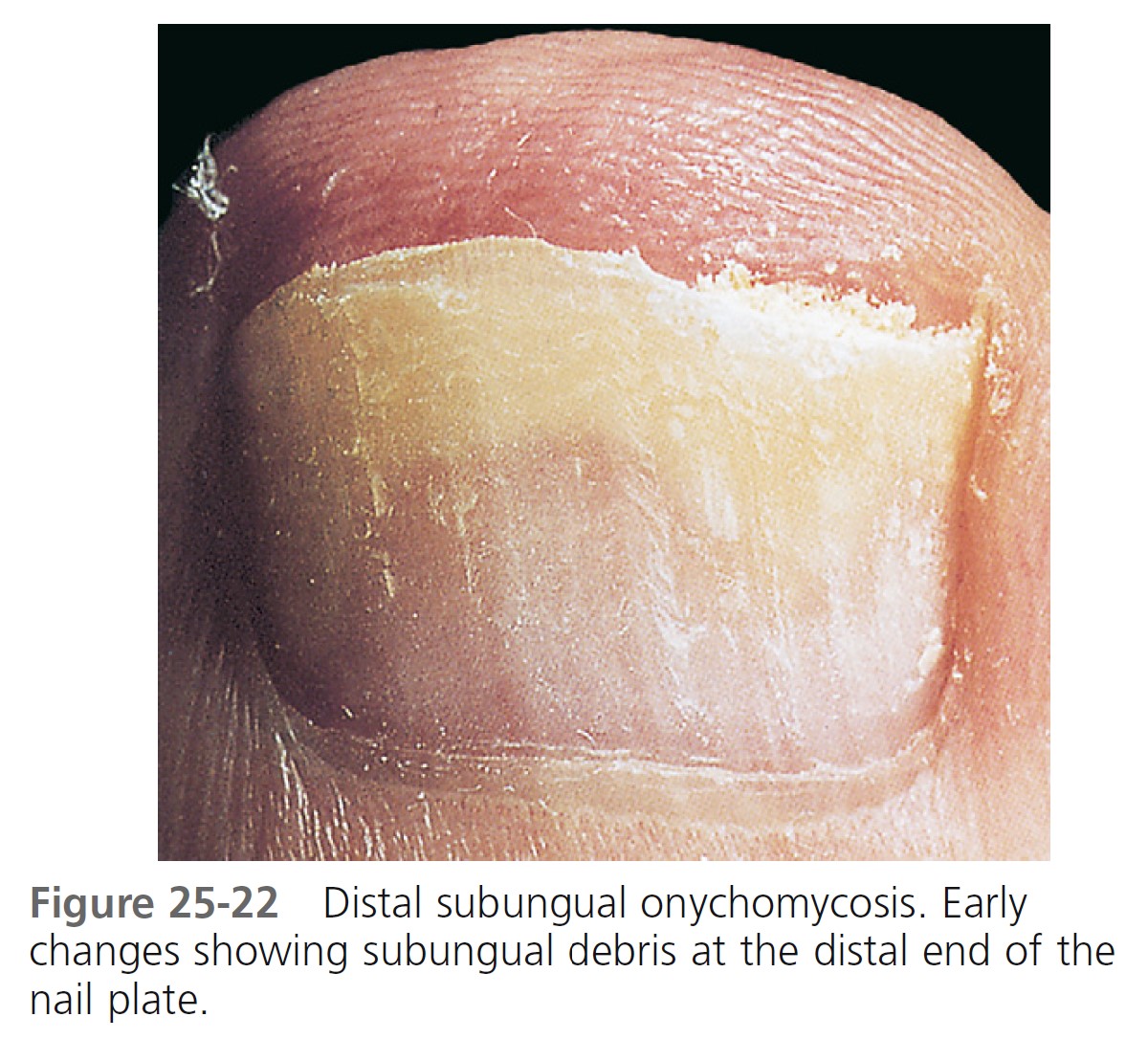

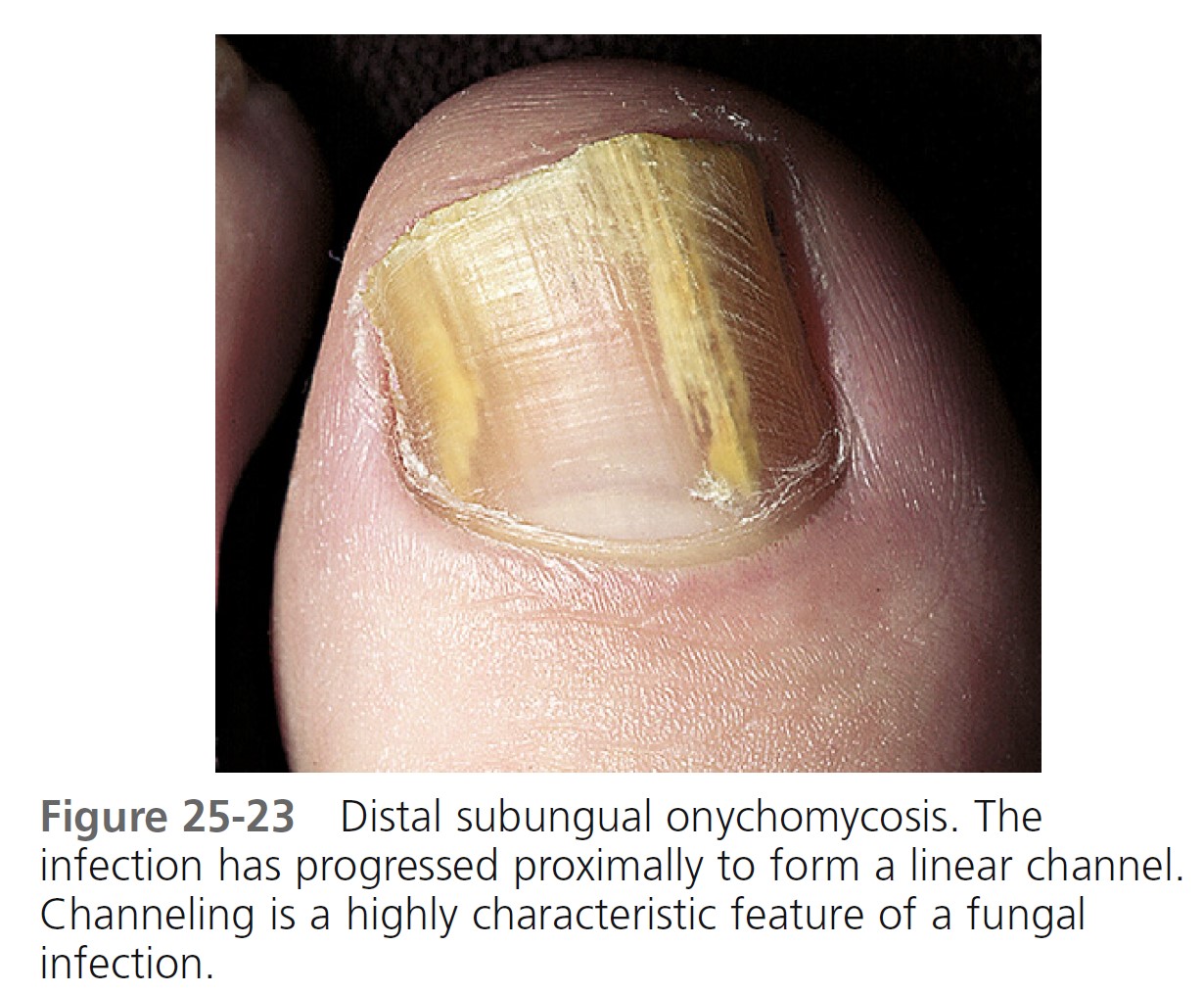

Distal subungual onychomycosis. Distal subungual onychomycosis ( Figures 25-22 and 25-23 ) is the most common pattern of nail invasion. Fungi invade the hyponychium, the distal area of the nail bed. The distal nail plate turns yellow or white as an accumulation of hyperkeratotic debris causes the nail to rise and separate from the underlying bed. Fungus grows in the substance of the plate, causing it to crumble and fragment. A large mass composed of thick nail plate and underlying debris may cause discomfort with footwear.

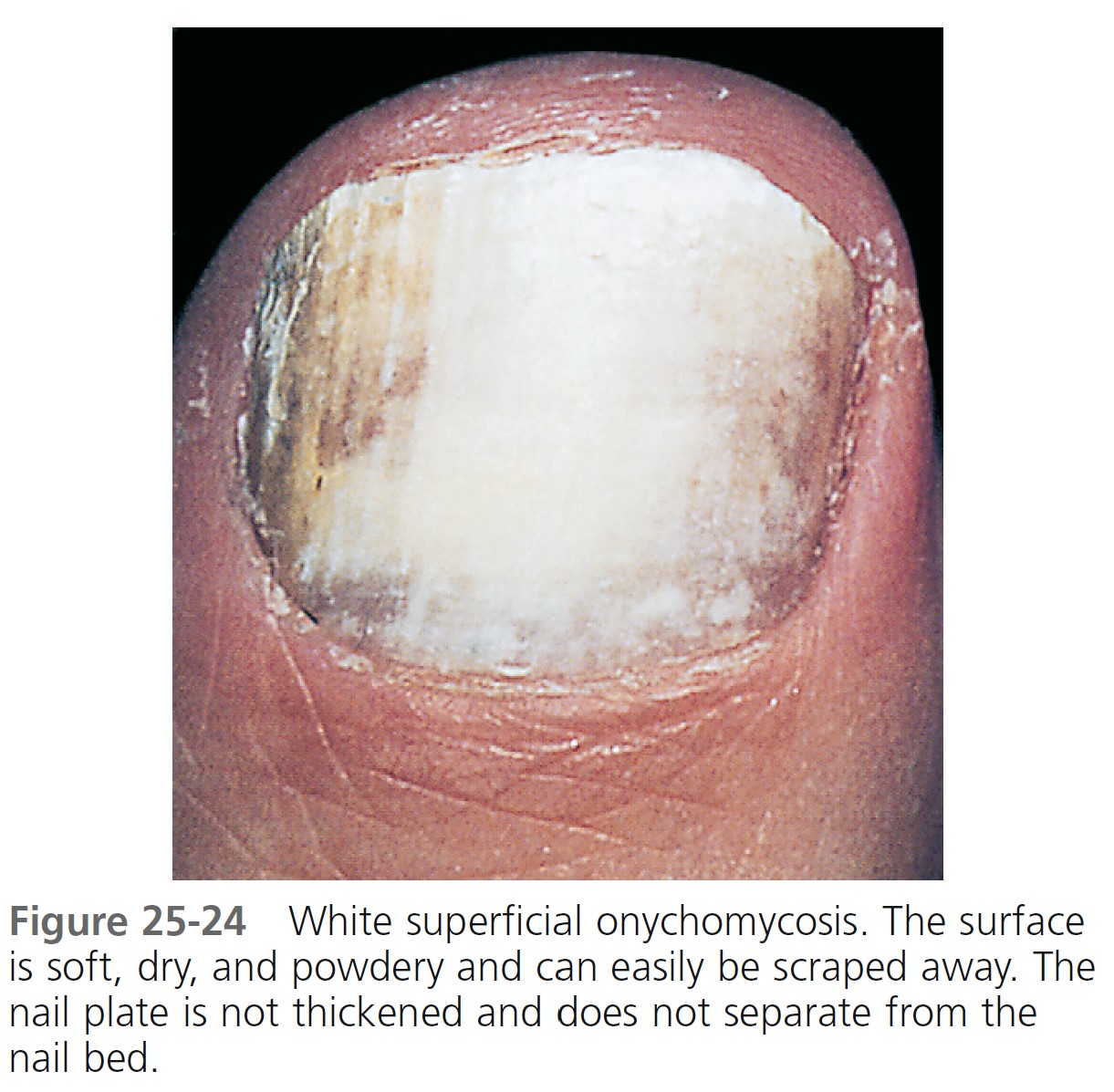

White superficial onychomycosis. This is caused by surface invasion of the nail plate, most often by T. mentagrophytes. The surface of the nail is soft, dry, and powdery and can easily be scraped away ( Figure 25-24 ). The nail plate is not thickened and remains adherent to the nail bed.

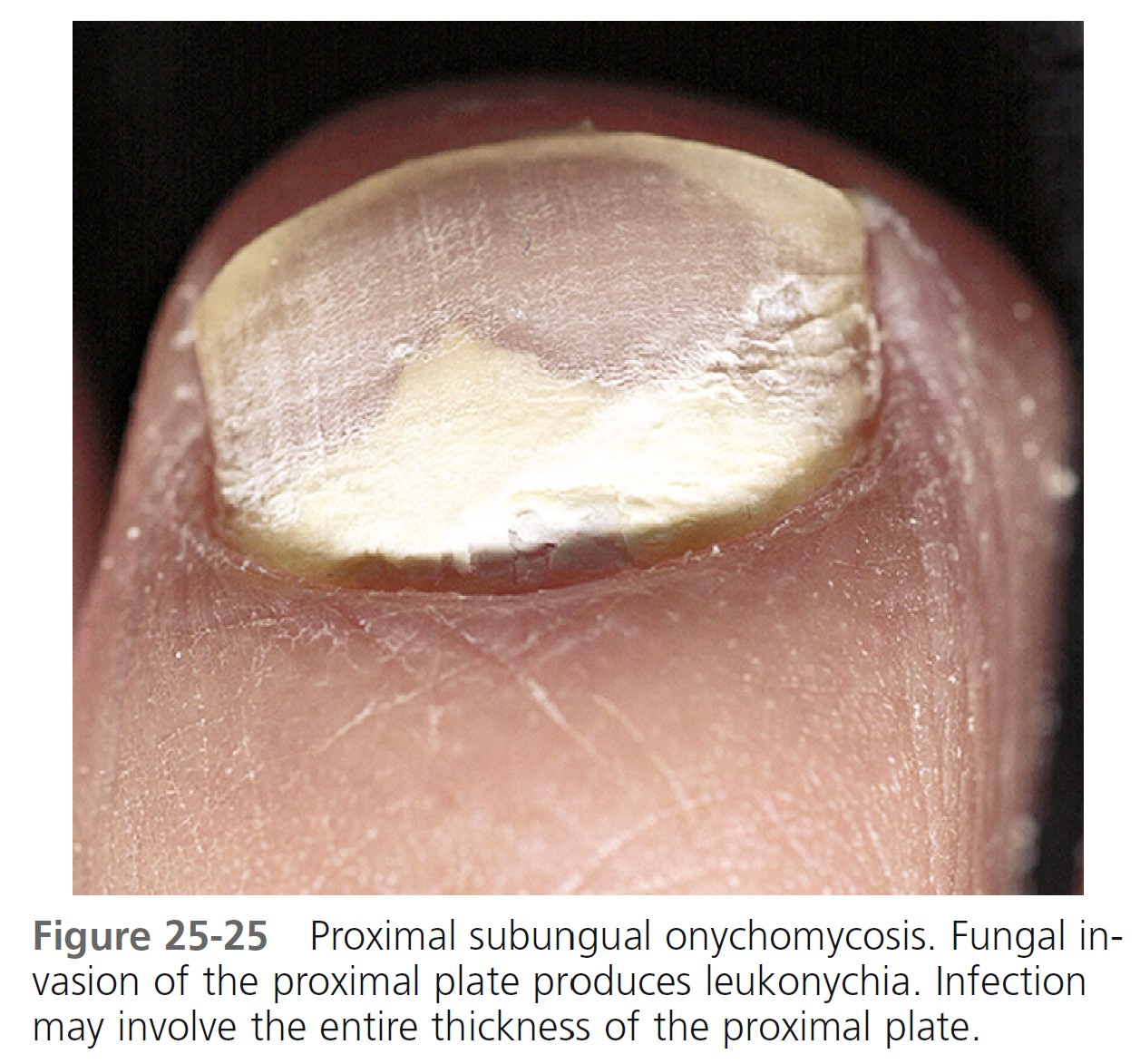

Proximal subungual onychomycosis. Microorganisms enter the posterior nailfold-cuticle area, migrate to the underlying matrix, and finally invade the nail plate from below. Infection occurs within the substance of the nail plate, but the surface remains intact. Hyperkeratotic debris accumulates and causes the nail to separate ( Figure 25-25 ). Transverse white bands begin at the proximal nail plate and are carried distally with outward growth of the nail plate. T. rubrum is the most common cause. This is the most common pattern seen in patients with AIDS.

Candida onychomycosis. Nail plate infection caused by C. albicans is seen almost exclusively in chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. It generally involves all of the fingernails. The nail plate thickens and turns yellow-brown.

There are many other patterns of infection. Linear, yellow or dark brown streaks appear at the distal end and grow proximally in some patterns. In others, some or all of the nail plate may appear yellow; in these areas, the nail can be separated from the underlying bed.

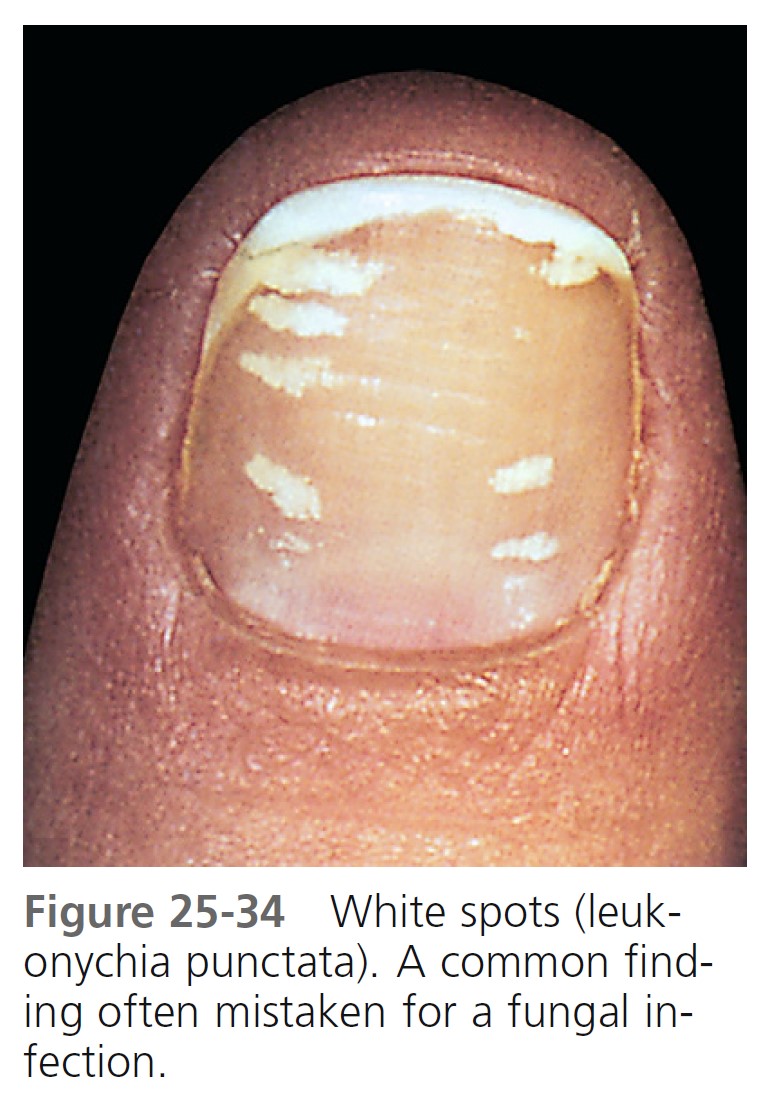

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS. Psoriasis is most commonly confused with onychomycosis, and the two diseases may coexist. More confusion exists, since psoriatic nail disease may present as an isolated phenomenon without other cutaneous signs. The single distinguishing feature of psoriasis, pitting of the nail plate surface, is not a feature of fungal infection. Leukonychia, the occurrence of white spots or bands that appear proximally and proceed out with the nail, is probably caused by minor trauma and may be confused with proximal subungual onychomycosis. Eczema or habitual picking of the proximal nailfold induces the nail plate to be wavy and ridged, but its substance remains intact and hard. Numerous, less common nail diseases may be confused with tinea unguium.

GENETIC PREDISPOSITION. Trichophyton rubrum onychomycosis frequently occurs in several members of the same family in different generations. The infection is rare in persons marrying into infected families. Predisposed individuals may acquire T. rubrum infection in childhood from their infected parents. The infection remains asymptomatic and localized to the plantar region. Nail invasion begins in adult life, possibly from nail trauma.

QUALITY-OF-LIFE ISSUES. Onychomycosis physically and psychologically affects patients’ lives. It is capable of having a negative effect on quality of life via social stigma and disrupting daily activities. The problems are embarrassment, functional problems at work, reduction in social activities, fear of spreading the infection to others, and a significant incidence of pain. Onychomycosis can interfere with standing, walking, and exercising. Associated physical impairments can result in paresthesia, pain, discomfort, and loss of manual dexterity. Patients may also suffer from loss of self-esteem and social interaction. Insurance companies consider this disease a cosmetic nuisance and are reluctant to pay for treatment unless the patient is physically impaired by the disease.

TREATMENT

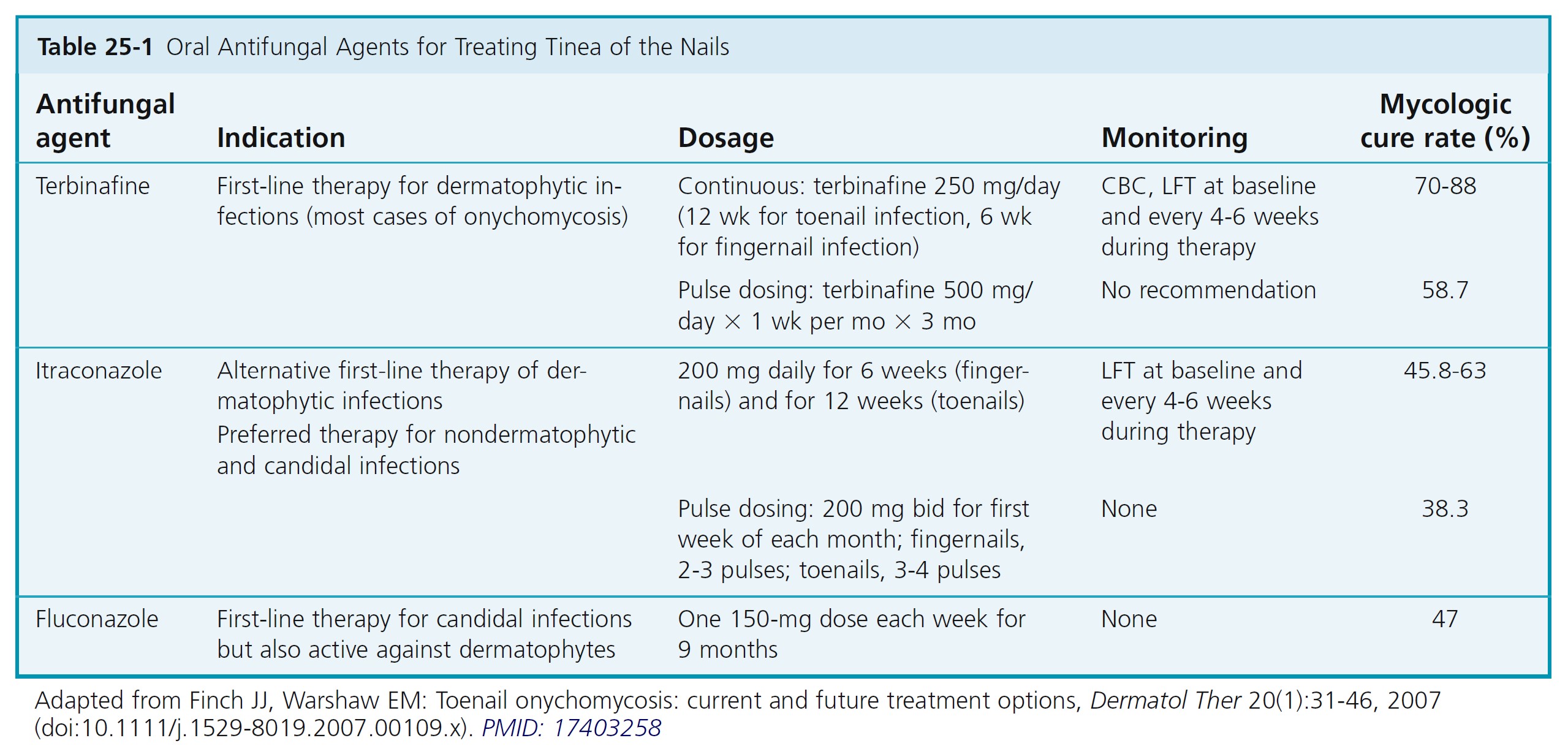

ORAL AGENTS: TERBINAFINE, ITRACONAZOLE, FLUCONAZOLE. These drugs penetrate keratinizing tissue. The levels reached in the nail plate exceed those in plasma. Therapeutic levels persist in the nails for at least 1 month after discontinuation of therapy. Terbinafine has higher cure rates and a slower relapse rate. Itraconazole can influence the level of many drugs. Terbinafine is relatively free of interactions. Table 25-1 discusses recommended dosages.

Continuous terbinafine. Continuous treatment with terbinafine is the optimal therapy for onychomycosis. Continuous terbinafine (250 mg/day for 12 weeks) is significantly more effective than intermittent itraconazole (400 mg/day for 1 week every 4 weeks for 12 weeks) in the treatment of toenail onychomycosis. Continuous terbinafine is more effective than intermittent terbinafine regimens and is just as safe. PMID: 16467022

Griseofulvin is less effective than the newer antifungal agents. Periodic debridement of infected nail during the course of treatment may increase the cure rate.

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS. A variety of clinical signs present at the initial clinical evaluation indicate a poor overall prognosis for ultimate cure of onychomycosis (see p. 960 ).

RESPONSE TO TREATMENT. Cure of all 10 toenails may be unattainable. A nail plate with a normal appearance is not always attainable after a successful therapeutic onychomycosis regimen. Some residual change is likely after chronic infection. Successful eradication of the fungus may leave the nail abnormal and the residual changes may be unrelated to infection or a result of damage to the nail unit from long-standing disease (e.g., onycholysis). Clinical and mycologic criteria are important to ascertain both the diagnosis and the resolution of onychomycosis. In severe cases of onychomycosis, up to 10% of the nail surface is likely to remain abnormal in appearance even when mycology indicates a cure of fungal infection.

It takes 12 to 18 months for a newly formed toenail plate and 4 to 6 months for a fingernail to replace a diseased nail. Immediately after completion of therapy the nail usually does not appear to be clear of infection. A proximal area of normal-appearing nail, representing newly formed nail plate that is devoid of infection, may be present. Visible clearance of the infection will occur after the process of nail plate turnover is complete. If onychomycosis is suggested based on clinical observation, diagnostic laboratory tests should be performed. If these produce negative findings, they should be repeated. Clinical manifestations of other nail disorders—such as psoriasis, neoplasms, and lichen planus—may mimic those of onychomycosis but can be diagnosed by nail-unit biopsy.

PREVENTING RECURRENCE. Preventing recurrence of tinea pedis may prevent recurrence of onychomycosis. Prolonged use of a topical antifungal agent applied around the toes, after clinical response of onychomycosis to an oral agent, may prevent nail reinfection. Use of a topical antifungal cream for 1 year after clinical cure of onychomycosis has prevented reinfection in the 12-month follow-up period. A twice weekly application of terbinafine cream in the nail area, between the toes and on the soles, would be a reasonable prevention program. Trauma to the tips of nails from tight-fitting shoes may be the single most important event for encouraging hyphae invasion in the region of the hyponychium that leads to distal subungual onychomycosis.

Shoes or boots that create a confined, damp, and warm atmosphere facilitate the development of fungal infection. Protect feet in communal showers. Medicated powders applied directly to the toe webs and soles (not poured into shoes) will help maintain a dry environment but will probably not prevent recurrence.

DRUG INTERACTIONS. Itraconazole has an affinity for cytochrome P-450 enzymes and therefore has the potential for interactions. Terbinafine is not metabolized through this system and has little potential for drug-drug interactions. Drug interactions are usually less severe with fluconazole than with itraconazole.

LABORATORY MONITORING. Many physicians check liver function and complete blood counts before and at 6 weeks during treatment with terbinafine. Laboratory tests are not required during pulse dosing of itraconazole.

SAFETY OF ORAL AGENTS. Terbinafine and itraconazole are available in a generic from at a considerable savings. Patients have the impression that they cause many side effects, especially liver disease. These drugs have been used in Europe and the United States for several years. They have a very low incidence of serious side effects.

RECURRENCE RATES. Studies of terbinafine and itraconazole demonstrated that at 5 years, 23% of terbinafine treated patients and 53% of itraconazole-treated patients experienced a relapse or reinfection, after achieving mycologic cure at 1 year. At 5-year follow-up, 13% of the itraconazole group and 46% of the terbinafine group remained disease-free. Another study showed that 11% of terbinafine responders showed evidence of relapse 18 to 21 months after cessation of treatment. PMID: 17403258 Patients treated with itraconazole or terbinafine who experience recurrence of onychomycosis can be retreated with response rates similar to those of the initial course.

MECHANICAL REDUCTION OF INFECTED NAIL PLATE. A nail clipper with pliers handles may be used to remove substantial amounts of hard, thick debris. One should insert the pointed tip of the instrument as far down as possible between the diseased nail and the nail bed. Adherent thick nail plate can be reduced by sanding or cutting the surface layers with the clippers. Removal of the infected nail may accelerate resolution of the infection.

SURGICAL REMOVAL. Painful or extremely infected nails (usually the nail of the first toe) can be removed by a simple surgical procedure.

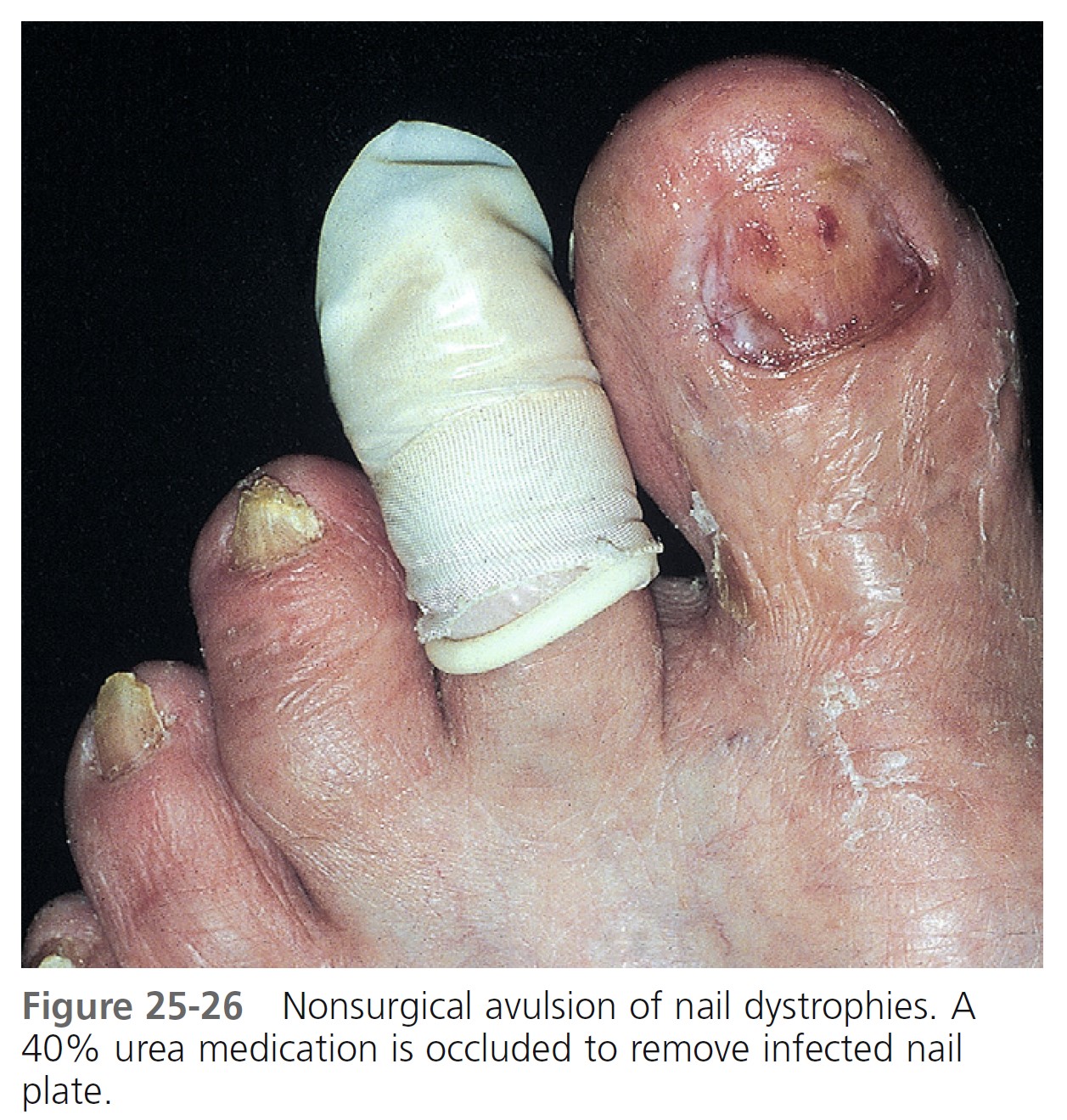

NONSURGICAL AVULSION OF NAIL DYSTROPHIES. If nails are very thick at baseline, consider occlusion with 40% urea cream under tape in addition to oral therapy. Symptomatic dystrophic nails may be painlessly removed with a urea compound ( Figure 25-26 ). The technique has its greatest application in removing hypertrophic mycotic nails and can be used to treat other hypertrophic nail conditions of the nail plate, such as psoriatic nails. The procedure also facilitates subsequent treatment with topical antifungal agents. The technique removes only grossly diseased or dystrophic nails, not normal nails. Forty percent urea gel or cream is commercially available or by prescription.

Cloth adhesive tape is used to cover the normal skin surrounding the affected nail plate, which has been pretreated with tincture of benzoin. The urea cream is generously applied directly to the nail surface and covered with a piece of plastic wrap. This in turn is covered with a finger that is cut from a plastic glove and held in place with adhesive tape. Patients are instructed to keep the area completely dry with the aid of plastic gloves or booties.

An alternate technique uses adhesive felt (moleskin) and waterproof, stretchable tape (Blenderm). A nail-shaped hole is cut in a piece of moleskin, and the moleskin is applied, sticky surface down, on the dorsal aspect of the toe so that just the nail is exposed through the hole. The well is fi lled with the urea cream and covered with Blenderm tape. The patient returns to the physician in 7 to 10 days. At that time the treated nails are removed, when possible, either by lifting the entire nail plate from the nail bed or by cutting the abnormal portions with a nail cutter. This is followed by light curettage until a clinically normal nail is reached at all margins.

Trauma

ONYCHOLYSIS

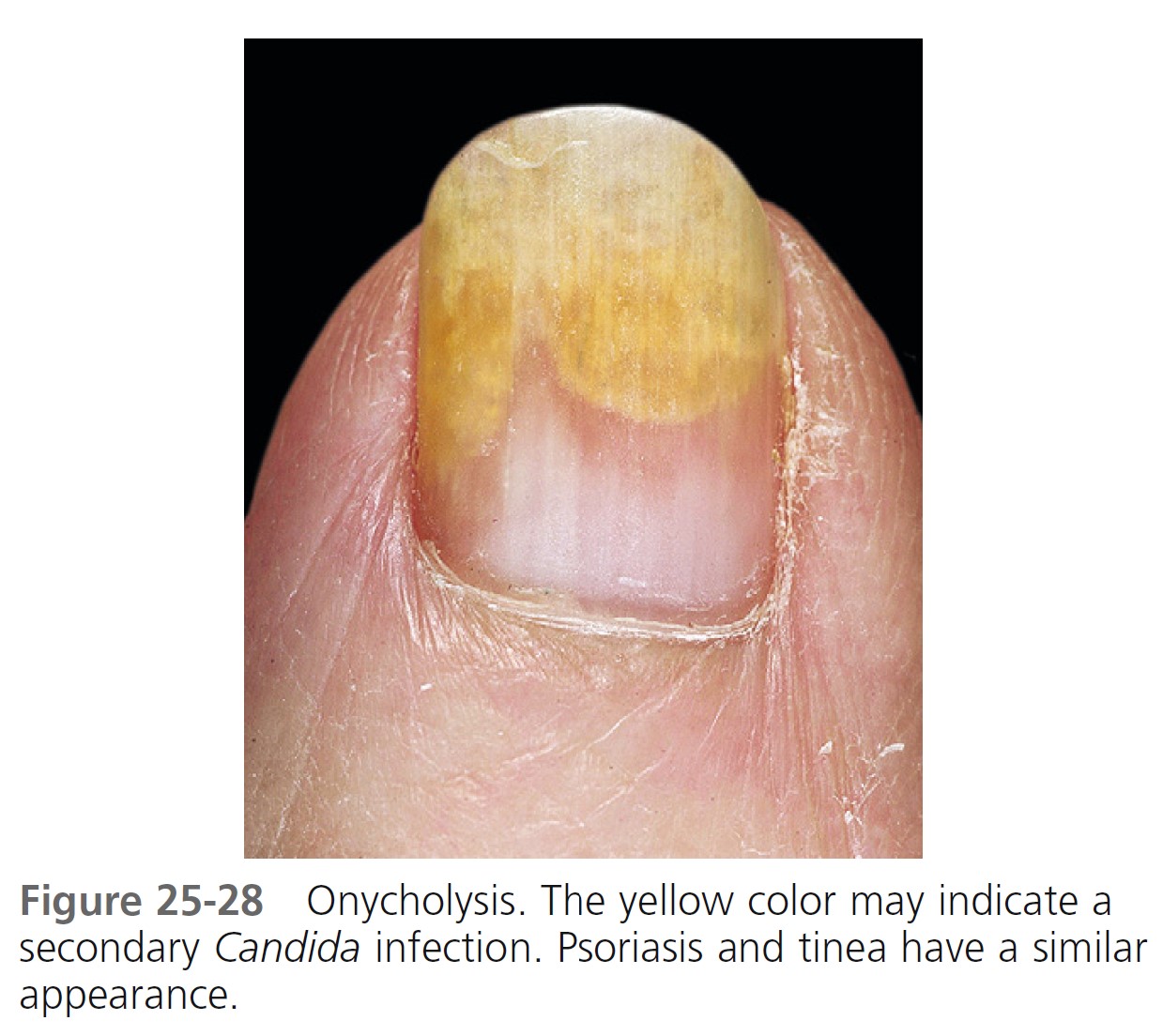

Onycholysis, the painless separation of the nail from the nail bed, is common. Separation usually begins at the distal groove and progresses irregularly and proximally, causing part or most of the plate to become separated. The nonadherent portion of the nail is opaque with a white ( Figure 25-27 ), yellow ( Figures 25-28 and 25-29 ), or green tinge. The causes of onycholysis include psoriasis, trauma, Candida or Pseudomonas infections, internal drugs, PUVA photochemotherapy, contact with chemicals, maceration from prolonged immersion, and allergic contact dermatitis (e.g., to nail hardener and adhesives). Onycholysis is known to be associated with thyroid disease (especially hyperthyroidism). Consider screening patients with unexplained onycholysis for asymptomatic thyroid disease.

When other signs of skin disease are absent, onycholysis is most frequently seen in women with long fingernails. With normal activity, the extended nail inadvertently strikes objects and acts as a lever to pry the nail from the nail bed. Forcing a stylus between the nail plate and bed while manicuring can cause separation.

TREATMENT. All of the separated nail is removed, and the fingers are kept dry. Removing the separated nail eliminates the lever, and dryness discourages infection. One should not cover the cut nails; occlusion promotes maceration. Any form of manipulation should be discouraged. Avoid exposure to contact irritants. Yeast commonly grows in the space between the nail and nail bed. Use liquid topical agents that can flow under the nail such as fungoid tincture that contains miconazole. Use oral fluconazole (Diflucan) for resistant cases. A short course of fluconazole (e.g., 150 mg daily for 5 to 7 days) may have to be repeated as the nail grows out.

PHOTOONYCHOLYSIS. Onycholysis may be precipitated by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. Photoonycholysis may occur with the use of tetracycline antibiotics and cytotoxic drugs. Nail changes with the taxanes, primarily docetaxel, are reported in up to 30% to 40% of patients. Prolonged weekly exposure to paclitaxel, other taxanes, and anthracyclines causes onycholysis in some patients, which may be precipitated by exposure to sunlight. Patients receiving these drugs should protect their nails from sunlight. The reaction does not warrant discontinuation of therapy.

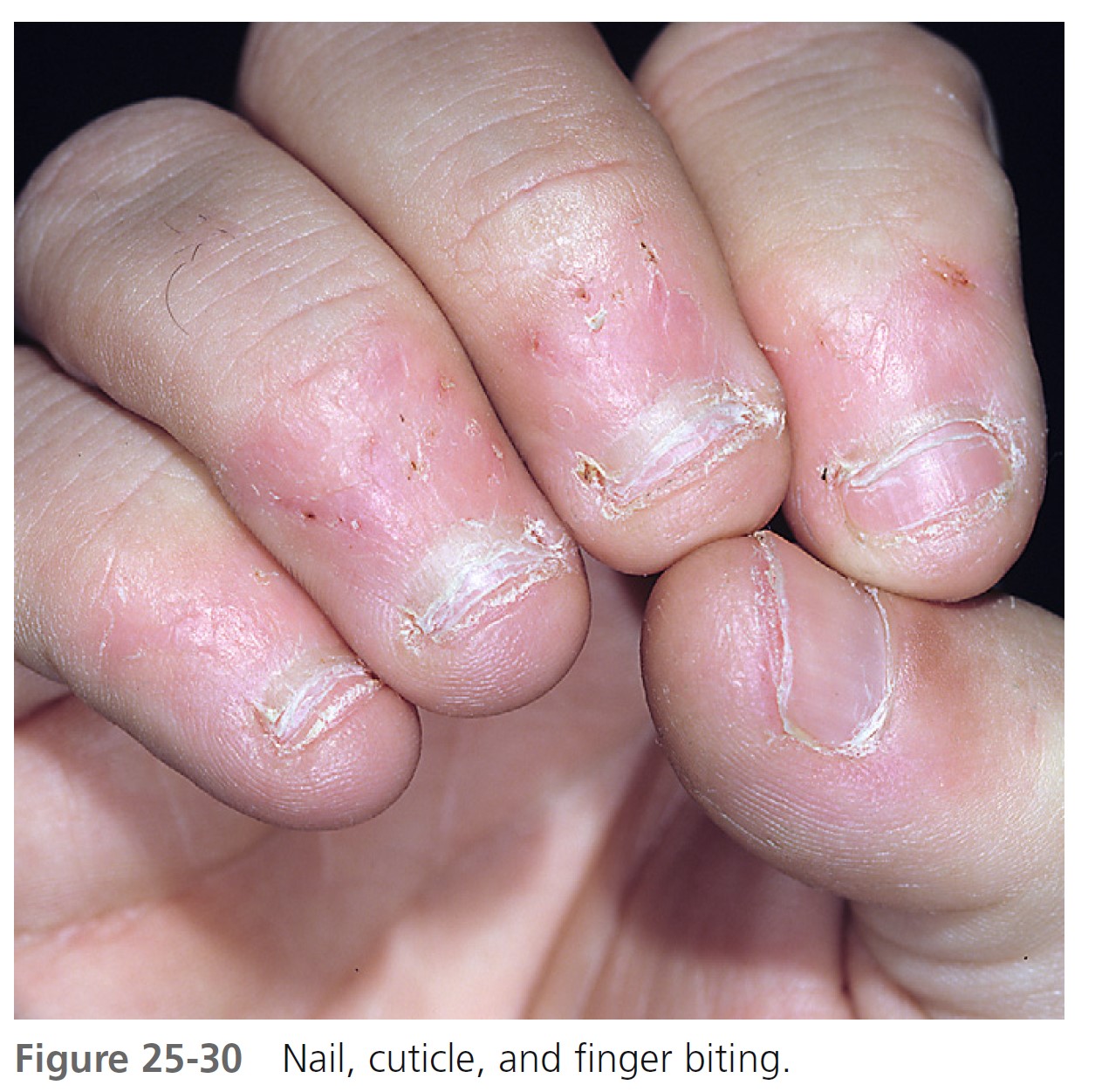

NAIL AND CUTICLE BITING

Nail biting is a nervous habit that usually begins in childhood and lasts for years. One or all nails may be chewed as far as the lunula. The nail plate is chiseled and bitten from the nail bed by the teeth. Nail growth occurs during periods of physical activity, but periods of physical inactivity seem to promote zealous nail biting. Thin strips of skin on the lateral and proximal nailfold may also be stripped ( Figure 25-30 ).

Patients are aware of their habit but seem powerless to control it. In one study mild aversion such as painting the nail plate with a distasteful preparation such as Nail Cure (Purepac) or Sally Hansen Nail Biter resulted in significant improvements in nail length. A second effective method of habit reversal is to have patients perform a competing response whenever they have the urge to nail bite or find themselves biting their nails.

NAIL PLATE EXCORIATION

Digging or excoriating the nail plate is much less common than biting. This destructive practice may result in gross deformity of the nail plate.

HANGNAIL

Triangular strips of skin may separate from the lateral nailfolds, particularly during the winter months. Attempts at removal may cause pain and extension of the tear into the dermis. Separated skin should be cut before extension occurs. Constant lubrication of the fingertips with skin creams (e.g., Aquaphor ointment) and avoidance of repeated hand immersion in water are beneficial.

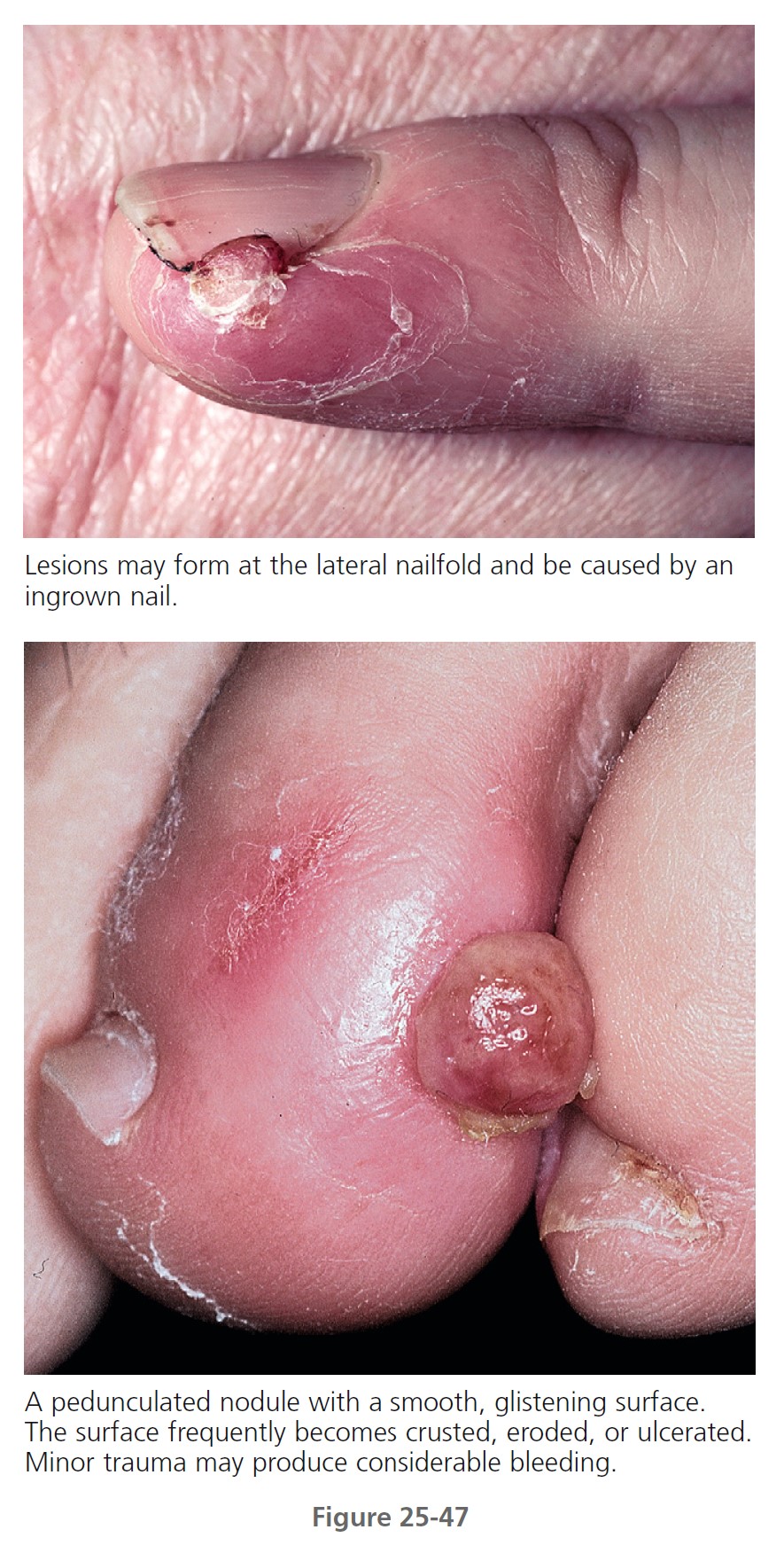

INGROWN TOENAIL

Ingrown fingernails and toenails are common; the large toe is most frequently affected. The nail pierces the lateral nailfold and enters the dermis, where it acts as a foreign body. The first signs are pain and swelling. The area of penetration becomes purulent and edematous as exuberant granulation tissue grows alongside the penetrating nail ( Figure 25-31 ). Ingrown nails are caused by lateral pressure of poorly fitting shoes, improper or excessive trimming of the lateral nail plate, or trauma.

TREATMENT

Ingrown nail without inflammation. Separate the distal anterior tip and lateral edges of an ingrown toenail from the adjacent soft tissue with a wisp of absorbent cotton coated with collodion. This gives immediate relief of pain and provides a firm runway for further growth of the nail. The collodion fixes the cotton in place, waterproofs the area, and permits bathing. The cotton insert may need reinsertion in 3 to 6 weeks. Cotton without collodion may be used, but it may have to be replaced frequently. This method is not applicable to patients with infected acute inflammation of the lateral nailfold.

Ingrown nail with inflammation. The lateral nailfold is infiltrated with 1% or 2% lidocaine (Xylocaine). Nail splitting scissors are inserted under the ingrown nail parallel to the lateral nailfold. The tip is inserted toward the matrix until resistance is met, and the wedge-shaped nail is then cut and removed. Granulation tissue is reduced with a silver nitrate application or removed with a curette. For a few days, the inflamed site is treated with a water or Burow’s cool, wet compress until the swelling and inflammation have subsided. Shoes should be worn that allow the toes to fall naturally, without compression. The new nail is forced up and over the lateral nailfold by inserting cotton under the lateral nail margin and allowing it to remain in place for days or weeks.

Recurrent ingrown nail. Patients with recurrent ingrown nails may require the use of liquid phenol for permanent destruction of the lateral portions of the nail matrix. The use of oral antibiotics as an adjunctive therapy in treating ingrown toenails does not play a role in decreasing the healing time or postprocedure morbidity.

SUBUNGUAL HEMATOMA

Subungual hematoma ( Figure 25-32 ) may be caused by trauma to the nail plate, which causes immediate bleeding and pain. The quantity of blood may be sufficient to cause separation and loss of the nail plate. The traditional method of puncturing the nail with a red-hot paperclip tip remains the quickest and most effective method of draining the blood. Alternatively, a carbon dioxide laser can be used to melt the nail at the center of the discolored area and decompress the hematoma. No anesthesia is required with this procedure. Trephining the nail with a hand drill, dental drill, or a fine-point scalpel blade can be painful because of the pressure required to puncture the nail. Often digital nerve block is necessary when drilling methods are used. Trauma to the proximal nailfold causes hemorrhage that may not be apparent for days. The nail plate may emerge from the nailfold with bloodstains that remain until the nail grows out. Young children with subungual hematoma may be victims of child abuse.

NAIL HYPERTROPHY

Gross thickening of the nail plate may occur with tight fitting shoes or other forms of chronic trauma. The nail plate is brown, very thick, and points to one side ( Figure 25-33 ). Shoes compress the nail plate against the toe and cause pain. The substance of the nail plate may be reduced with sandpaper or a file, or the nail can be removed and the nail matrix permanently destroyed with phenol so that the nail will not regrow.

WHITE SPOTS OR BANDS

White spots (leukonychia punctata) in the nail plate, a very common finding, possibly result from cuticle manipulation or other mild forms of trauma ( Figure 25-34 ). The spots or bands may appear at the lunula or may appear spontaneously in the nail plate and subsequently disappear or grow with the nail. Psoriasis of the mid-nail matrix can also produce this change.

DISTAL PLATE SPLITTING (BRITTLE NAILS)

The splitting into layers or peeling of the distal nail plate may resemble or be analogous to the scaling of dry skin ( Figure 25-35 ). This nail change is found in approximately 20% of the adult population. Repeated water immersion and the frequent use of nail polish removers increase the incidence of brittle nails, particularly in women. Local measures to rehydrate the nail plate should be initiated. A moisturizer may be applied after the nails have been soaked in water. Protection with rubber-over-cotton gloves and application of heavy lubricants (e.g., Aquaphor ointment) directly to the nail plate provide improvement. The moisturizing agent may be applied under occlusion with a white cotton glove or sock. Nail enamel may slow the evaporation of water from the nail plate. It should be removed and reapplied no more than once a week. A number of nail conditioning products (e.g., Elon nail products) are available from Dartmouth pharmaceuticals online ( www.ilovemynails.com ) and in pharmacies. Patients with brittle nails who receive the B-complex vitamin biotin (2.5 mg/day) may improve and have up to a 25% increase in nail plate thickness. A 10-mg dose of silicon daily, a useful form of which is choline-stabilized orthosilicic acid, has a similar effect.

HABIT-TIC DEFORMITY

Habit-tic deformity is a common finding and is caused by biting or picking a section of the proximal nailfold of the thumb with the index fingernail. Although the condition is most common to the thumbnails, all nails can be affected. The lesion is often noted as an incidental finding in a patient seeking treatment for another cutaneous disease. The resulting defect consists of a longitudinal band of horizontal grooves that often have a yellow discoloration. The band extends from the proximal nailfold to the tip of the nail ( Figure 25-36 ). This should not be confused with the nail rippling that occurs with chronic paronychia or chronic eczematous inflammation of the proximal nailfold. The ripples of chronic inflammation appear as rounded waves ( Figure 25-37 ), in contrast to the closely spaced, sharp grooves produced by continual manipulation.

The method of formation is demonstrated for the patient. Some patients are not aware of their habit, and others who admit to nail picking may not realize that they have created the defect. Patients who discontinue manipulation are able to grow relatively normal nails; there are those, however, who find it impossible to stop.

From a psychiatric perspective, it is often unclear how to classify habit-tic disorders. The heterogeneity of behaviors complicates the diagnostic process. In some cases it might be classified as obsessive-compulsive disorder. In other cases, the behavior is automatic, bearing similarities to the impulse control disorder trichotillomania, which may be related to obsessive-compulsive disorders. Obsessive compulsive disorder sometimes responds to the serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine (Prozac), and patients with habit-tic deformity may respond to this medication.

MEDIAN NAIL DYSTROPHY

Median nail dystrophy is a distinctive nail plate change of unknown origin. A longitudinal split appears in the center of the nail plate. Several fine cracks project from the line laterally, giving the appearance of a fir tree. The thumb is most often affected ( Figure 25-38 ). There is no treatment, and after a few months or years the nail can be expected to return to normal. Recurrences are possible.

PINCER NAILS (CURVATURE)

Inward folding of the lateral edges of the nail results in a tube- or pincer-shaped nail ( Figure 25-39 ). The nail bed is drawn up into the tube and may become painful. The toenails are more commonly involved than the fingernails. Shoe compression is thought to cause pincer nails, but the etiology is uncertain. If pain is significant, surgical removal of the nail or reconstruction of the nail unit is required.

THE NAIL AND INTERNAL DISEASE

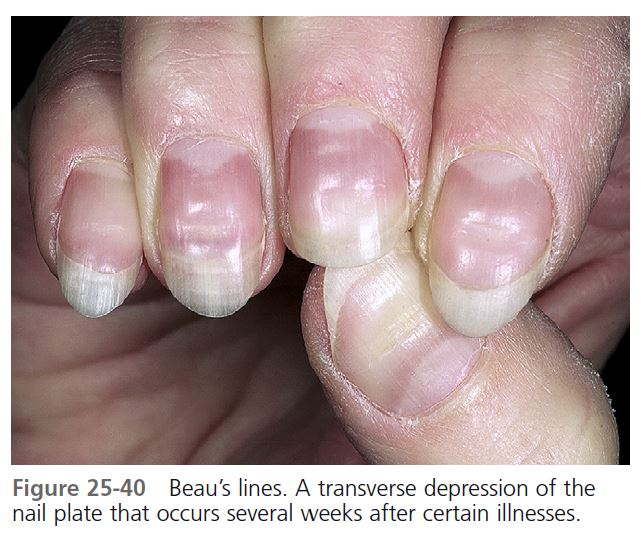

BEAU’S LINES

Beau’s lines are transverse depressions of all of the nails that appear at the base of the lunula weeks after a stressful event has temporarily interrupted nail formation ( Figure 25-40 ). The lines progress distally with normal nail growth and eventually disappear at the free edge. They develop in response to many diseases, such as syphilis, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, myocarditis, peripheral vascular disease, and zinc deficiency, and to illnesses accompanied by high fevers, such as scarlet fever, measles, mumps, hand-foot and-mouth disease, and pneumonia, and to chemotherapeutic agents.

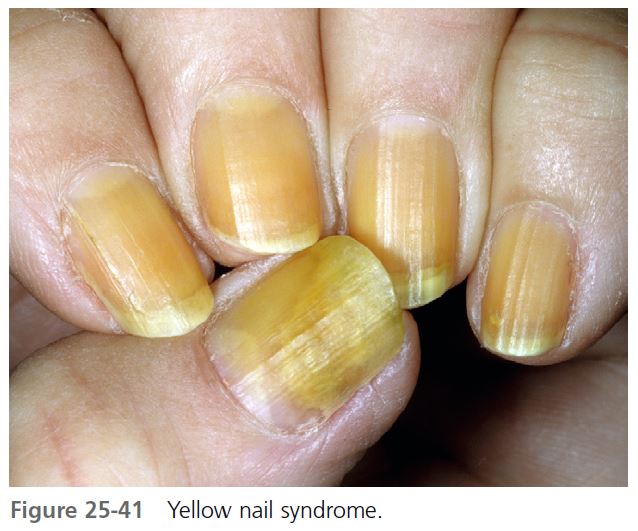

YELLOW NAIL SYNDROME

Yellow nail syndrome is a rare acquired condition defined by the presence of yellow nails associated with lymphedema and/or chronic respiratory manifestations. Chronic respiratory manifestations include pleural effusions, bronchiectasis, chronic sinusitis, and recurrent pneumonias. The spontaneous appearance of yellow nails occurs before, during, or after certain respiratory diseases and in diseases associated with lymphedema. Patients note that nail growth slows and appears to stop. The nail plate may become excessively curved, and it turns dark yellow ( Figure 25-41 ). The surface remains smooth or acquires transverse ridges, indicating variations in the growth rate; nails grow at less than half the normal rate. Partial or total separation of the nail plate may occur. The nails show an increased curvature about the long axis, the cuticles and lunulae are lost, and usually all the nails are involved. The nails grow very slowly, at a rate of 0.1 to 0.25 mm/week, compared with 0.5 to 2 mm/week for normal adult fingernails. Nails that grow slowly often become thicker. The lymphatic impairment associated with yellow nail syndrome appears to be secondary, and predominantly functional in nature, rather than as a result of structural changes. Yellowish nail pigmentation has been reported in patients with AIDS. The nails may spontaneously improve, even when the associated disease does not improve. Oral vitamin E in dosages of up to 800 international units/day for up to 18 months may help. Yellow nails that were treated with a 5% vitamin E solution (containing DL -α-tocopherol in dimethylsulfoxide), two drops twice a day to the nail plate, showed marked clinical improvement and an increase in nail growth rate. Yellow nails improve in about half of patients, often without specific therapy.

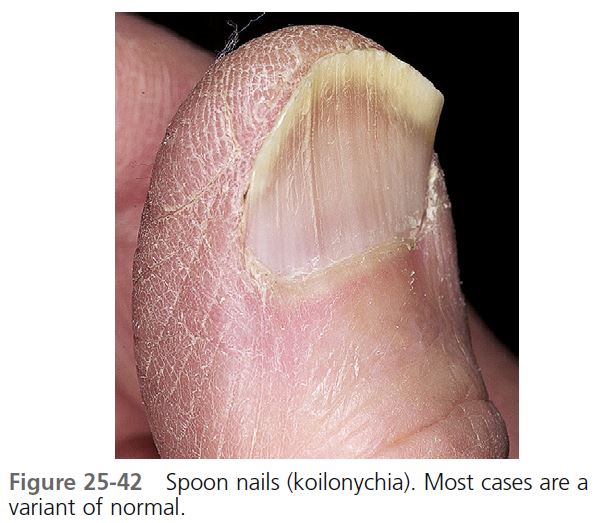

SPOON NAILS

Lateral elevation and central depression of the nail plate cause the nail to be spoon shaped; this is called koilonychia ( Figure 25-42 ). Spoon nails are seen in normal children and may persist a lifetime without any associated abnormalities. The spontaneous onset of spoon nails has been reported to occur with iron deficiency anemia and in 50% of patients with idiopathic hemochromatosis. The nail reverts to normal when the anemia is corrected.

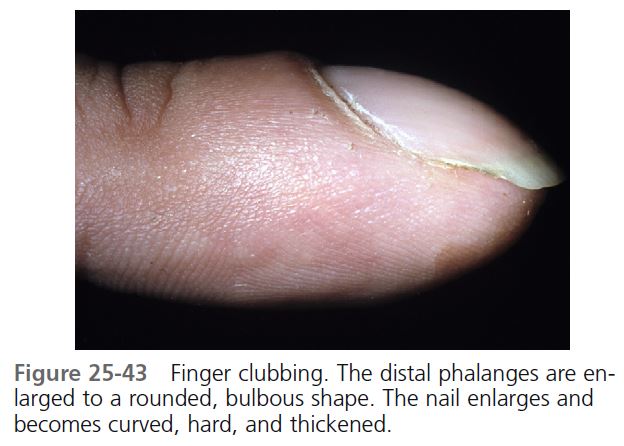

FINGER CLUBBING

Finger clubbing (Hippocratic nails) is a distinct feature associated with a number of diseases, but it may occur as a normal variant. Clubbing is painless unless associated with pulmonary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, and then there is periarticular pain and swelling, most often in the wrists, ankles, knees, and elbows ( Figure 25-43 ).

The features of clubbing occur in stages. The first is periungual erythema and a softening of the nail bed, giving a spongy sensation on palpation. The proximal nailfold feels as though it is floating on the underlying tissue. Next there is an increase in the normal 160-degree angle between the nail bed and the proximal nailfold. Lovibond (Lovibond’s angle) showed that when viewed from the lateral aspect, an angle of greater than 180 degrees made by the nail as it exits the proximal nailfold can differentiate true clubbing from other conditions, such as nail curving and paronychia.

An increase in the depth of the distal phalanges is the last change. The distal phalanges of the fingers and toes are enlarged to a rounded, bulbous shape. The nail enlarges and becomes curved, hard, and thickened. The process usually takes years.

Vascular endothelial growth factor may play a central role in the development of clubbing. It is a platelet-derived factor induced by hypoxia and is produced by diverse malignancies.

All patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease have clubbing. In North America, 80% of acquired clubbing is associated with pulmonary disease. Clubbing is associated with a variety of lung diseases, cardiovascular disease, cirrhosis, colitis, and thyroid disease. One third of patients with lung cancer have evidence of clubbing. The changes are permanent. PMID: 17976417

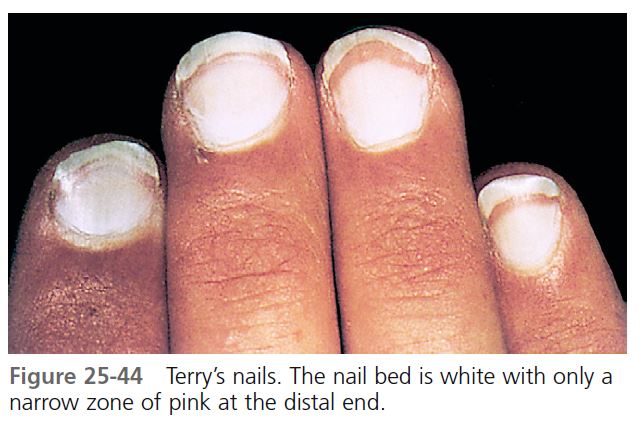

TERRY’S NAILS

Terry’s nails are white or light pink but retain a 0.5- to 3-mm normal, pink, distal band ( Figure 25-44 ). The findings are associated with cirrhosis, chronic congestive heart failure, adult-onset diabetes mellitus, and age. It has been speculated that Terry’s nails are a part of aging and that associated diseases “age” the nail. These changes are not associated with hypoalbuminemia or anemia.

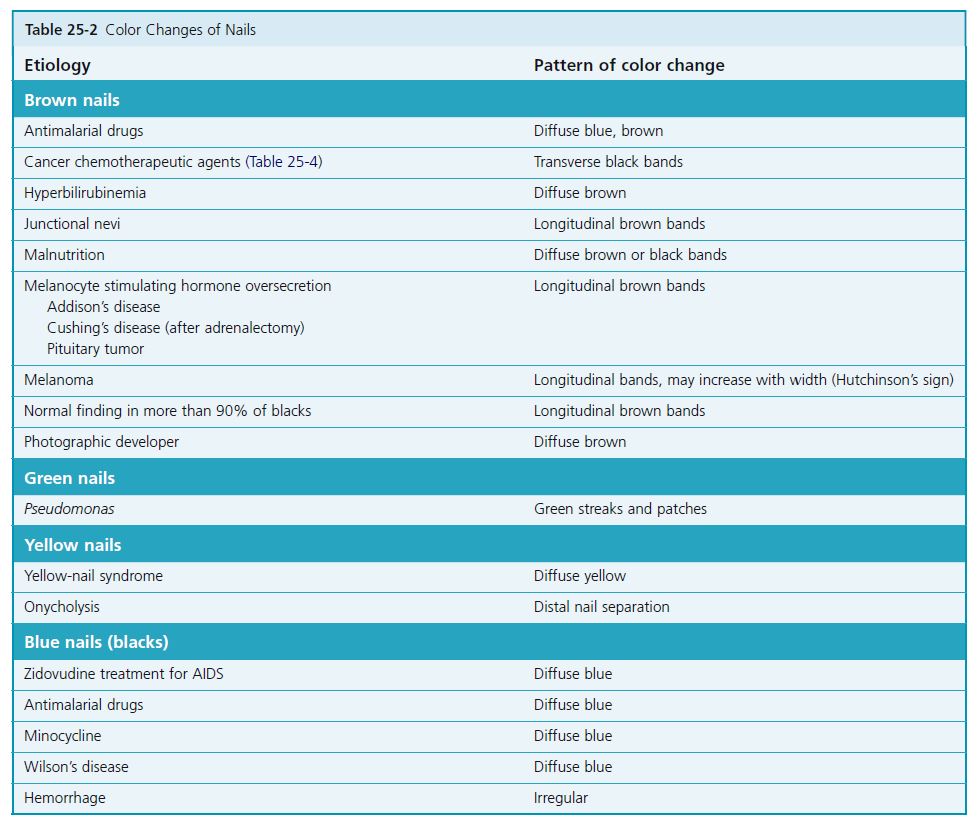

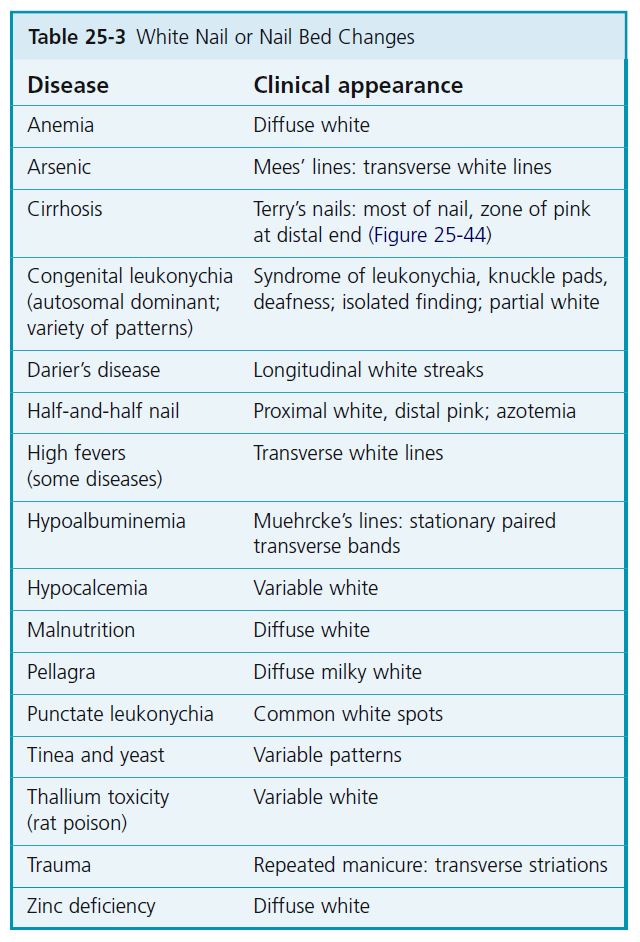

COLOR AND DRUG-INDUCED CHANGES

Changes in nail color may result from a color change in the nail plate or in the nail bed. Several articles list changes associated with nail pigmentation. Some of these changes are listed in Tables 25-2 and 25-3 . Cancer chemotherapeutic drugs have been associated with a variety of changes in the nail unit.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Numerous congenital syndromes involve nail changes. The most widely understood syndromes all have autosomal dominant inheritance patterns.

Among other signs of pachyonychia congenita, there are yellow, very thick nail beds with elevated nails, palmar and plantar hyperkeratosis, and white keratotic thickening of the tongue. Some patients have erupted teeth at birth. In nail-patella syndrome, there are defective short nails and small or absent patella, in addition to other signs.

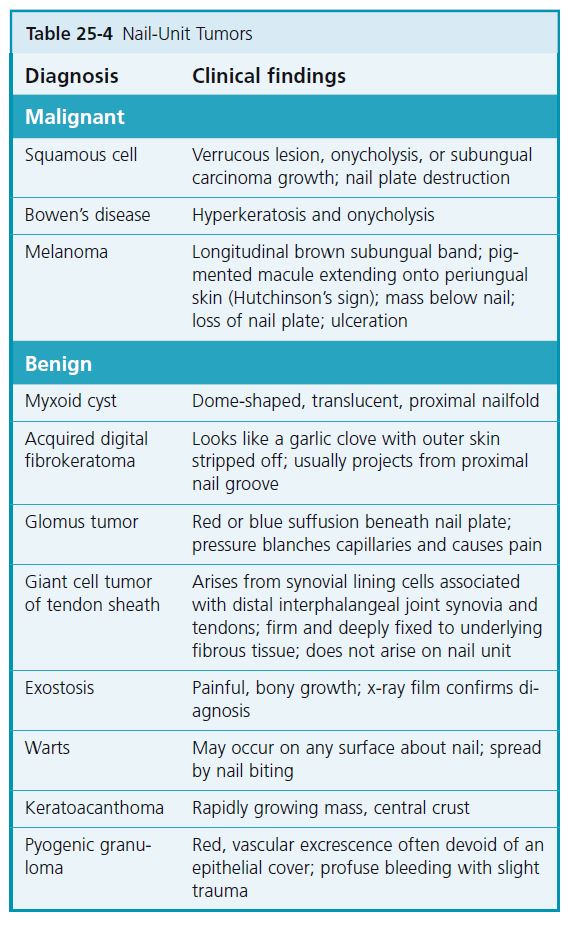

TUMORS

A limited number of tumors have been reported to occur about and under the nails ( Table 25-4 ).

WARTS. The most common periungual growth is the periungual wart. It is discussed in Chapter 12 . Warts are most common in children who bite their nails. Warts on the lateral nailfold and on the fingertip may extend deeply under the nail ( Figure 25-45 ). A longitudinal nail groove may result from warts situated over the nail matrix. Warts are epidermal growths, but, if massive, they can erode the underlying bony matrix by displacement.

DIGITAL MUCOUS CYSTS. Digital mucous cysts (focal mucinosis) are not true cysts but rather a focal collection of mucin lacking a cystic lining. These soft, dome-shaped, translucent, pink-white structures occur on the dorsal surface of the distal phalanx of the middle-aged and the elderly ( Figure 25-46 ). These structures contain a clear, viscous, jellylike substance that exudes if the cyst is incised. There are two types. The cysts on the proximal nailfold are not connected to the joint space or tendon sheath. They

result from localized fibroblast proliferation. Compression of the nail matrix cells induces a longitudinal nail groove. The cysts located on the dorsal-lateral finger at the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint are probably caused by herniation of tendon sheaths or joint linings and are related to ganglion and synovial cysts.

Simple surgical excision, intralesional steroid injections, and unroofing of the cyst followed by electrodesiccation and curettage have a high recurrence rate.

Excision of the lesion with its pedicle and associated portions of the joint capsule affords a high cure rate but may result in subsequent partial loss of motion.

Cryosurgery. Cryosurgery using either the open-spray or the cryoprobe technique yields a cure rate of up to 75%. A local anesthetic is injected before treatment. The roof of the cyst is removed with scissors and the gelatinous material is expelled to facilitate freezing of the base of the lesion. Either a flat cryoprobe of approximately the same size as the cyst or a direct intermittent open spray to the center of the lesion is applied. The freeze time is 30 to 40 seconds when the cryoprobe technique is used and 20 to 30 seconds when the open-spray technique is used. The treated site becomes edematous and exudative, and a bulla develops in most cases. Healing is complete in 4 to 6 weeks. Lesions can be retreated if necessary.

Multiple punctures. A high cure rate may be achieved with the simple technique of repeated punctures and expression of the cyst contents ( Figure 25-46 , B ). Cysts that resisted multiple needlings are usually reduced to small, asymptomatic nodules. Without anesthesia, the cyst is punctured with a medium-sized hypodermic needle (26 gauge) to a depth of 3 to 5 mm. The clear contents, sometimes tinged with blood, are squeezed out by fingertip pressure. The patient is given a supply of needles to repeat the procedure at home if the cyst recurs. From 1 to 10 needlings result in a cure or in an asymptomatic lesion.

Carbon dioxide laser. Carbon dioxide laser vaporization performed under local anesthesia resulted in complete remission in four out of six patients. No side effects of therapy occurred.

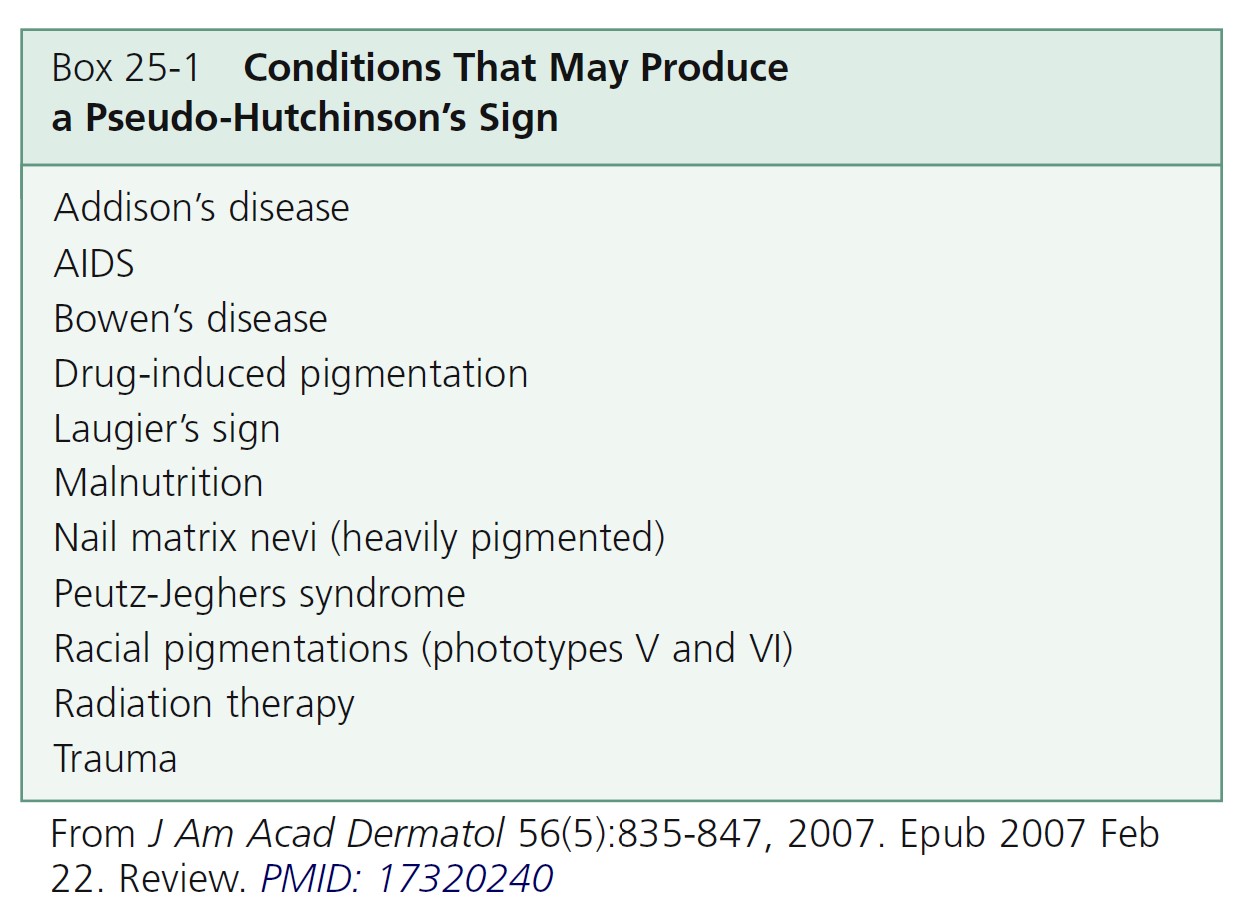

PYOGENIC GRANULOMA. Pyogenic granuloma occasionally occurs in the lateral nailfold. This benign mass of vascular tissue is removed with thorough electrodesiccation and curettage ( Figure 25-47 and see p. 906 ). Recurrences are common if any residual tissue is left. Periungual malignant melanoma can mimic pyogenic granuloma.

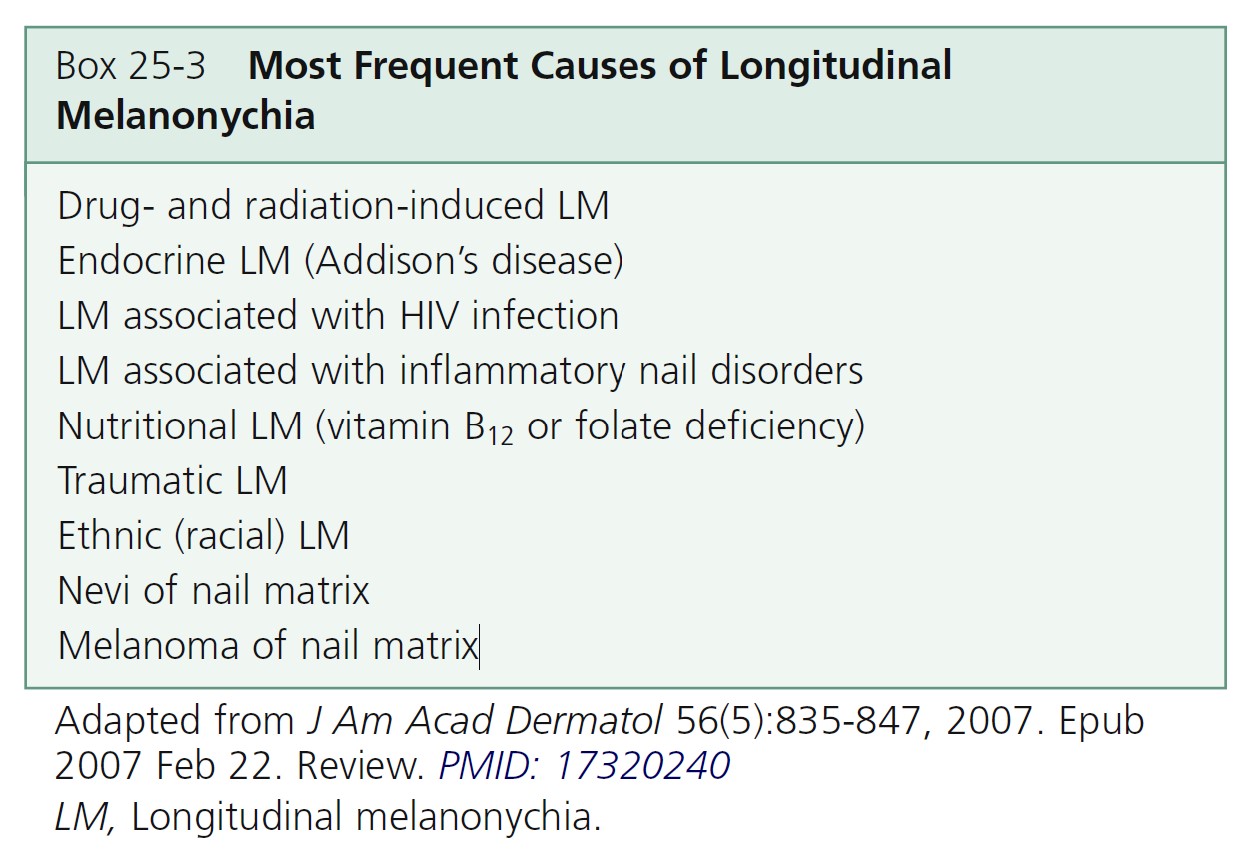

NEVI AND MELANOMA. Junctional nevi can appear in the nail matrix and produce a brown pigmented band. Brown longitudinal bands are common in blacks (see Figure 25-5 ) but rare in whites. Melanoma of the nail region, or melanotic whitlow, although rare, is a distinctive lesion ( Figures 25-48 and 25-49 ). Most are classified as acral lentiginous melanomas. The growth is usually painless and slow, and it can occur anywhere around or under the nail. The lesion may present as a pigmented band that increases in width. There has not been enough experience to make specific recommendations concerning the management of pigmented bands in whites. The spontaneous appearance of such a band is noteworthy to most physicians, who promptly require a biopsy. Benign subungual nevi are rare in whites, so subungual nevoid lesions should be regarded as malignant until proved otherwise. Nail matrix biopsy of longitudinal melanonychia is accomplished by shave, punch, or excision. Biopsies of possible subungual melanomas should be carried out by surgeons regularly doing such procedures. PMID: 17437887

Melanocytes in normal nail matrices are distributed in the basal layer and in the lower half of the epithelium. Therefore malignant melanoma of the nail matrix can arise from melanocytes situated in the squamous epithelium above the basal layer.

ABCDEF CRITERIA. The most salient features of subungual melanoma can be summarized according to the newly devised criteria that may be categorized under the first letters of the alphabet, namely, ABCDEF of subungual melanoma. In this system A stands for age (peak incidence being in the fifth to seventh decades of life) and for African Americans, Asians, and Native Americans, in whom subungual melanoma accounts for up to one third of all melanoma cases. B designates brown to black and with breadth of 3 mm or more and variegated borders. C stands for change in the nail band or lack of change in the nail morphology despite, presumably, adequate treatment. D indicates the digit most commonly involved. E stands for extension of the pigment onto the proximal and/or lateral nailfold (i.e., Hutchinson’s sign), and F designates family or personal history of dysplastic nevus or melanoma.

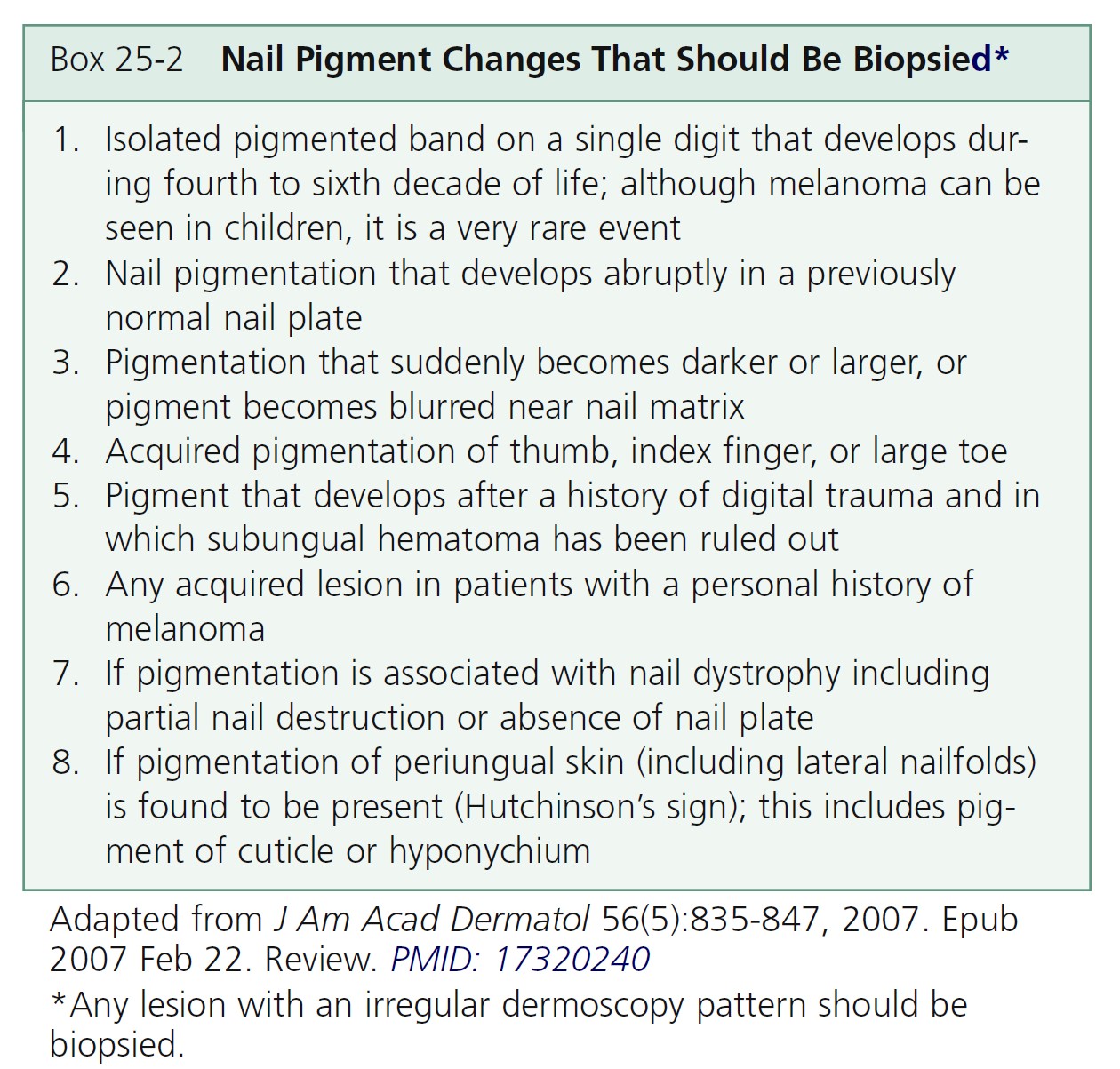

Hutchinson’s sign. Hutchinson’s sign, periungual extension of brown-black pigmentation from longitudinal melanonychia onto the proximal and lateral nailfolds, is an important indicator of subungual melanoma ( Figure 25-50 ). Periungual hyperpigmentation also occurs in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit. Hyperpigmentation of the nail bed and matrix may reflect through the “transparent” nailfolds simulating Hutchinson’s sign. Conditions that mimic Hutchinson’s sign are listed in Box 25-1.

Box 25-2 lists nail pigment changes that should be biopsied. Biopsy techniques are described on PMID: 1740326

LONGITUDINAL PIGMENTATION OF THE NAIL ( Figure 25-51 ). This is a common finding with multiple possible causes. History (time of onset, duration, medications) and exam (diameter, color) are important. Dermoscopy is also valuable. The most frequent causes of longitudinal nail pigmentation are listed in Box 25-3 .

Dermoscopy. Dermoscopy allows visual inspection through the stratum corneum and nail plate and provides magnification. The distal free edge of the nail plate is also examined. Proximal nail matrix pigment appears in the upper nail plate and pigment produced in the distal nail matrix appears in the lower part of the nail plate. The site to biopsy is derived from this information. An alternate method is to obtain a nail clipping and stain it with Fontana-Masson stain. The pathologist examines the distal edge and records the location of the pigment.