MELANOCYTIC NEVI

Nevi, or moles, are benign tumors composed of nevus cells that are derived from melanocytes. Many myths surround moles, for example, that hairs should not be plucked from moles or that moles should not be removed or disturbed.

NEVUS CELLS. The nevus cell differs from melanocytes. The nevus cell is larger, lacks dendrites, has more abundant cytoplasm, and contains coarse granules. Nevus cells aggregate in groups (nests) or proliferate in a non-nested pattern in the basal region at the dermoepidermal junction. Nevus cells in the dermis are classified into types A (epithelioid), B (lymphocytoid), and C (neuroid). Through a process of maturation and downward migration, type A epidermal nevus cells develop into type B cells and then into type C dermal nevus cells.

INCIDENCE AND EVOLUTION. Moles are so common that they appear on virtually every person. They are present in 1% of newborns and increase in incidence throughout infancy and childhood. The incidence peaks in the fourth to fifth decades. Nevi then diminish in number with advancing age.

Size and pigmentation may increase at puberty and during pregnancy. Nevi may occur anywhere on the cutaneous surface. There is a strong correlation between sun exposure and the number of nevi. Acquired nevi on the buttocks or female breast are unusual.

NEVI VS. MELANOMA. Nevi exist in a variety of characteristic forms that must be recognized to distinguish them from malignant melanoma. Except for certain types, such as large congenital nevi and atypical moles, most nevi have a very low malignant potential.

Nevi vary in size, shape, surface characteristics, and color. The important fact to remember is that each individual nevus tends to remain uniform in color and shape. Although various shades of brown and black may be present in a single lesion, the colors are distributed over the surface in a uniform pattern.

Melanomas consist of malignant pigment cells that grow and extend with little constraint through the epidermis and into the dermis. Such unrestricted growth produces a lesion with a haphazard or disorganized appearance, which varies in shape, color, and surface characteristics. The characteristics of uniformity cannot always be relied on to differentiate benign from malignant lesions because very early melanomas may appear quite uniform, having a round or oval shape with a uniform brown color.

EXAMINATION WITH A HAND LENS AND DERMOSCOPE. Careful inspection of suspicious lesions with a powerful hand lens and dermoscope will reveal a number of features that cannot be appreciated with the naked eye. Dermoscopy is discussed at the end of the chapter.

Common moles

Nevi may be classified as acquired or congenital, but a clinical classification based on appearance and conventional nomenclature is used here. Common acquired nevi appear after 6 months of age. They enlarge and increase in number through the third and fourth decades and then slowly disappear. Most are less than 5 mm in diameter. Fifty-five percent of adults have between 10 and 45 nevi greater than 2 mm in diameter. Nevi tend to be concentrated on sun-exposed sites.

CLASSIFICATION. Common moles are subdivided into three types—junction, compound, and dermal—based on the location of the nevus cells in the skin ( Figure 22-1 ). The three types represent sequential developmental stages in the life history of a mole. During childhood, nevi begin as flat junction nevi in which the nevus cells are located at the dermoepidermal junction. They evolve into compound nevi when some of the cells migrate into the dermis. Migration of all of the nevus cells into the dermis results in a dermal nevus. Dermal nevi usually form only in adults, but this evolution does not consistently occur. Nevi with cells confined to the dermoepidermal junction area tend to be flat, whereas those with cells confined to the dermis are usually elevated.

JUNCTION NEVI. Junction nevi are flat (macular) or slightly elevated, and they are light brown to brown-black with uniform pigmentation that may be slightly irregular ( Figure 22-2 ). The surface is smooth and flat to slightly elevated, and the border is round or oval and symmetric. Most lesions are hairless. Junction nevi vary in size from 0.1 to 0.6 cm; some are larger. Junction nevi may change into compound nevi after childhood, but they remain as junction nevi on palms, soles, and genitalia. Junction nevi are rare at birth and generally develop after the age of 2 years. Degeneration into melanoma is very rare.

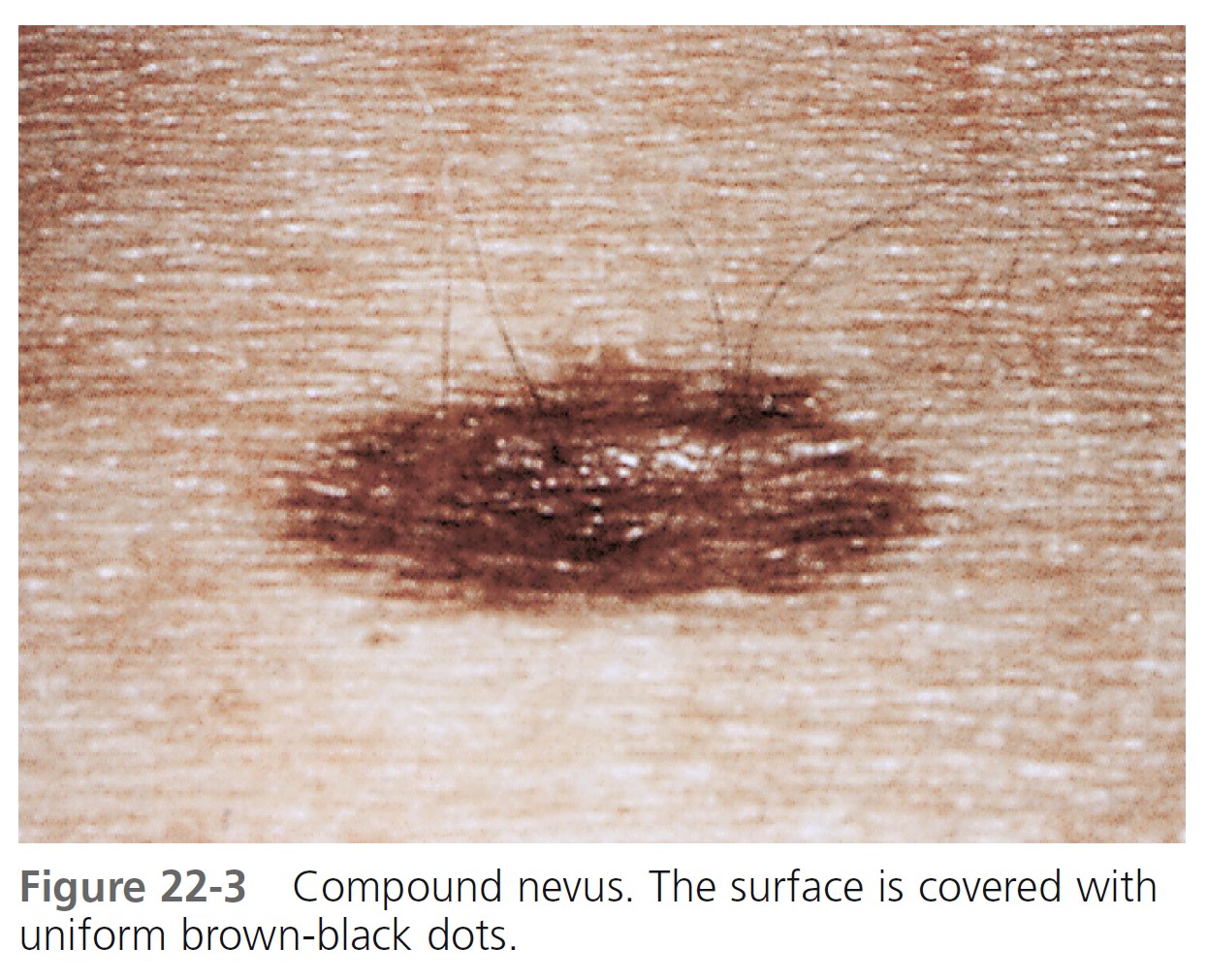

COMPOUND NEVI. Compound nevi are slightly elevated and flesh-colored or brown. They are elevated and smooth or warty and become more elevated with increasing age ( Figure 22-3 ). They are uniformly round, oval, and symmetric. Hair may be present. If a white halo appears at the periphery of the lesion, it is referred to as a halo nevus.

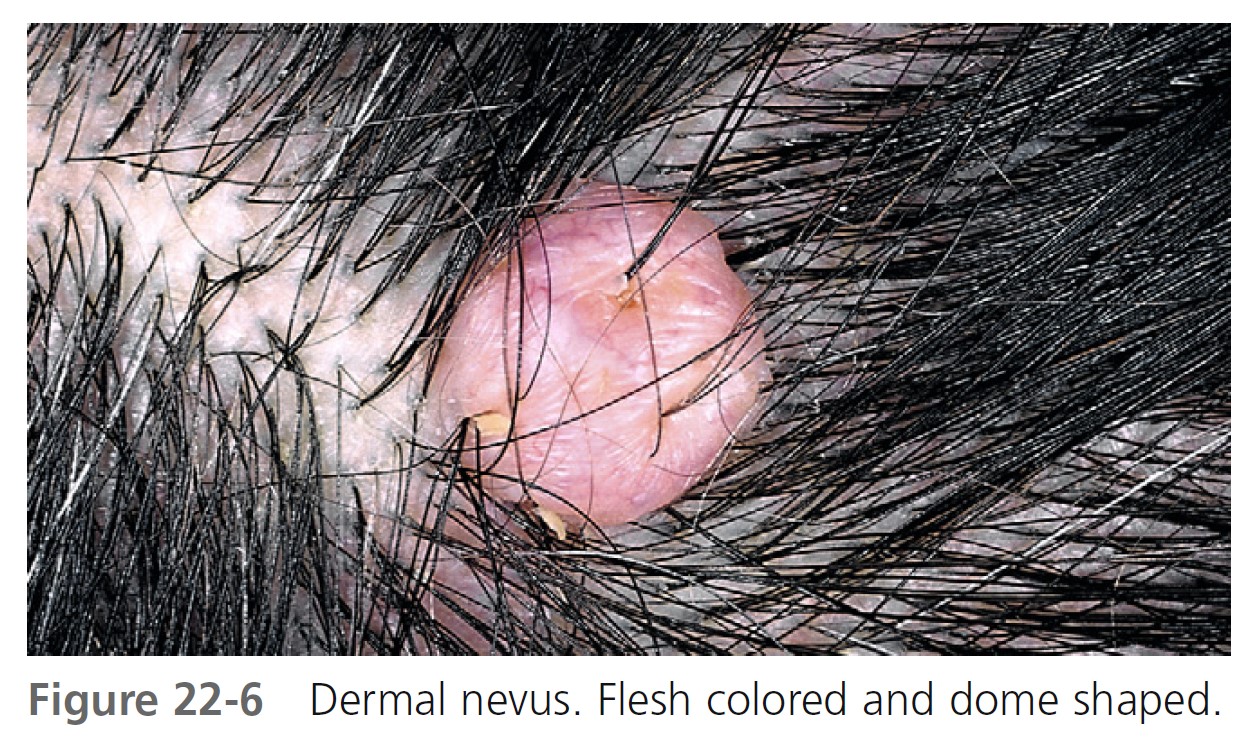

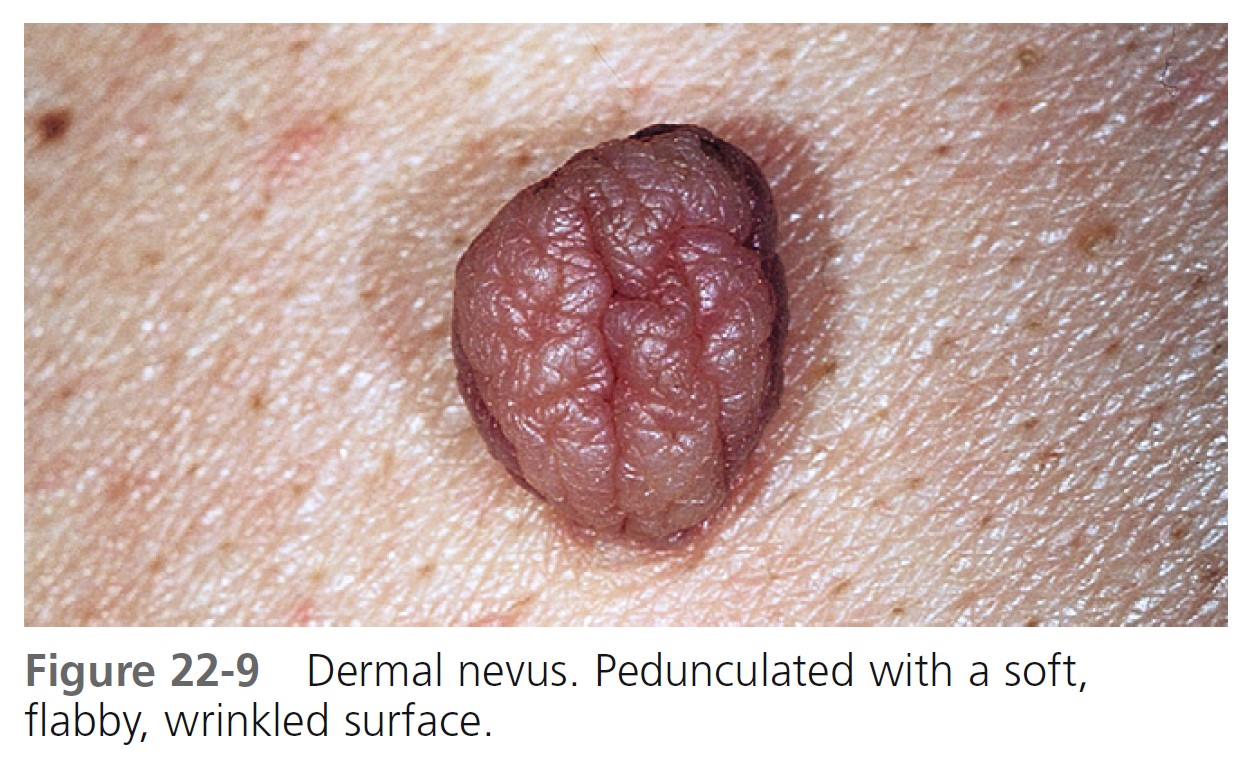

DERMAL NEVI. Dermal nevi are brown or black, but may become lighter or flesh-colored with age. Lesions vary in size from a few millimeters to a centimeter. The variety of shapes reflects the evolutionary process in which moles extend downward with age and nevus cells degenerate and become replaced with fat and fibrous tissue.

Dome-shaped lesions are the most common ( Figures 22-4 through 22-6 ). They generally appear on the face and are symmetric, with a smooth surface. They may be white or translucent, with telangiectatic vessels on the surface mimicking basal cell carcinoma. The structure may be warty ( Figure 22-7 ) or polypoid ( Figure 22-8 ). Pedunculated lesions with a narrow stalk are located on the trunk, neck, axillae, and groin. They may appear as a soft, flabby, wrinkled sack ( Figure 22-9 ).

Elevated nevi are exposed and are prone to trauma from clothing and other stimuli, often causing them to bleed and inflame, making some patients to suspect malignancy. A white border may appear, creating a halo nevus. Degeneration to melanoma is very rare, but dermal nevi may resemble nodular melanoma; therefore knowledge of duration and a history of recent change is important.

MANAGEMENT

SUSPICIOUS LESIONS. Any pigmented lesion suspected of being malignant should be biopsied or referred for a second opinion. Suspicious lesions should be completely removed by excisional biopsy down to and including subcutaneous tissue.

NEVI. Patients frequently request removal of nevi for cosmetic purposes. It is good practice to biopsy all pigmented lesions; therefore total removal by electrocautery should be avoided. Nevi are removed either by shave excision or by simple excision and closure with sutures. Most common nevi are small and shave excision is adequate.

RECURRENT PREVIOUSLY EXCISED NEVI (PSEUDOMELANOMA). Weeks to months after incomplete removal of a nevus, brown macular pigmentation may appear in the scar ( Figure 22-10 ). Some nevus cells remain with shave excision and partial repigmentation is possible. Residual pigmentation may be removed with electrocautery or cryosurgery. An unusual histologic picture resembling melanoma (pseudomelanoma) may follow partial removal of nevi. If the repigmented area is excised, the pathologist should be notified that the submitted tissue was acquired from a previously treated area. Histologically, the melanocytes appear atypical but are confined to the epidermis, and there is no lateral spread of individual melanocytes as is seen in melanoma.

NEVI WITH SMALL DARK SPOTS. A small percentage of small dark spots within melanocytic nevi are due to melanoma. These roundish areas of brown or black hyperpigmentation measure 3 mm or less in diameter and are located peripherally. Biopsy specimens of nevi with small dark dots should be sectioned to ensure histologic examination of this focus of hyperpigmentation.

Special forms

Special forms of pigmented lesions include congenital nevus, halo nevus, speckled lentiginous nevus, Becker’s nevus, benign juvenile melanoma (Spitz nevus), blue nevus, labial melanotic macules, and atypical nevi (dysplastic nevi, Clark nevi).

CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI. It is estimated that between 1% and 6% of the population have a congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN). Congenital melanocytic nevi (birthmarks) are present at birth and vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters, covering wide areas of the trunk, extremity, or face. Some lesions first become apparent during infancy. Not all pigmented lesions present at birth are congenital nevi; café-au-lait spots may also be present at birth. The largest lesions are referred to as giant hairy nevi. Giant congenital nevi on the trunk are referred to as bathing trunk nevi. Congenital nevi may contain hair; if present, it is usually coarse. Such nevi are uniformly pigmented, with various shades of brown or black predominating, but red or pink may be a minor or sometimes predominant color. Most are flat at birth but become thicker during childhood, and the surface becomes verrucous and sometimes nodular.

Size. CMNs are arbitrarily divided into groups according to their size in infancy: small (<1.5 cm in diameter), medium (1.5 to 19.9 cm in diameter), and large (>20 cm in diameter). Most grow in proportion to the growth of the child. CMNs on the head will increase in size by a factor of 1.5 and on the rest of the body by a factor of 3.

Histologic characteristics. Nevus cells occur (1) in the lower two thirds of the dermis, occasionally extending into the subcutis; (2) between collagen bundles distributed as single cells or cells in single file, or both; and (3) in the lower two thirds of the reticular dermis or subcutis associated with appendages, nerves, and vessels. Some congenital nevi do not have these microscopic features. Large congenital nevi usually do have the classic microscopic findings of congenital nevi, whereas small congenital nevi most often do not show these classic features. Medium sized congenital nevi may or may not show these classic microscopic features.

Malignant potential. Melanoma can develop in any CMN and the risk may correlate with the size of the nevus. The malignant potential of congenital nevi may be dependent on the histologic pattern of the lesion rather than the clinical size. Small congenital nevi frequently lack melanocytes in the deeper dermis. The increased risk of melanoma formation in large congenital nevi may be a result of transformation of cells residing deep in the dermis. Melanomas may develop in large CMNs before puberty; melanomas in small and medium CMNs generally develop at or after puberty.

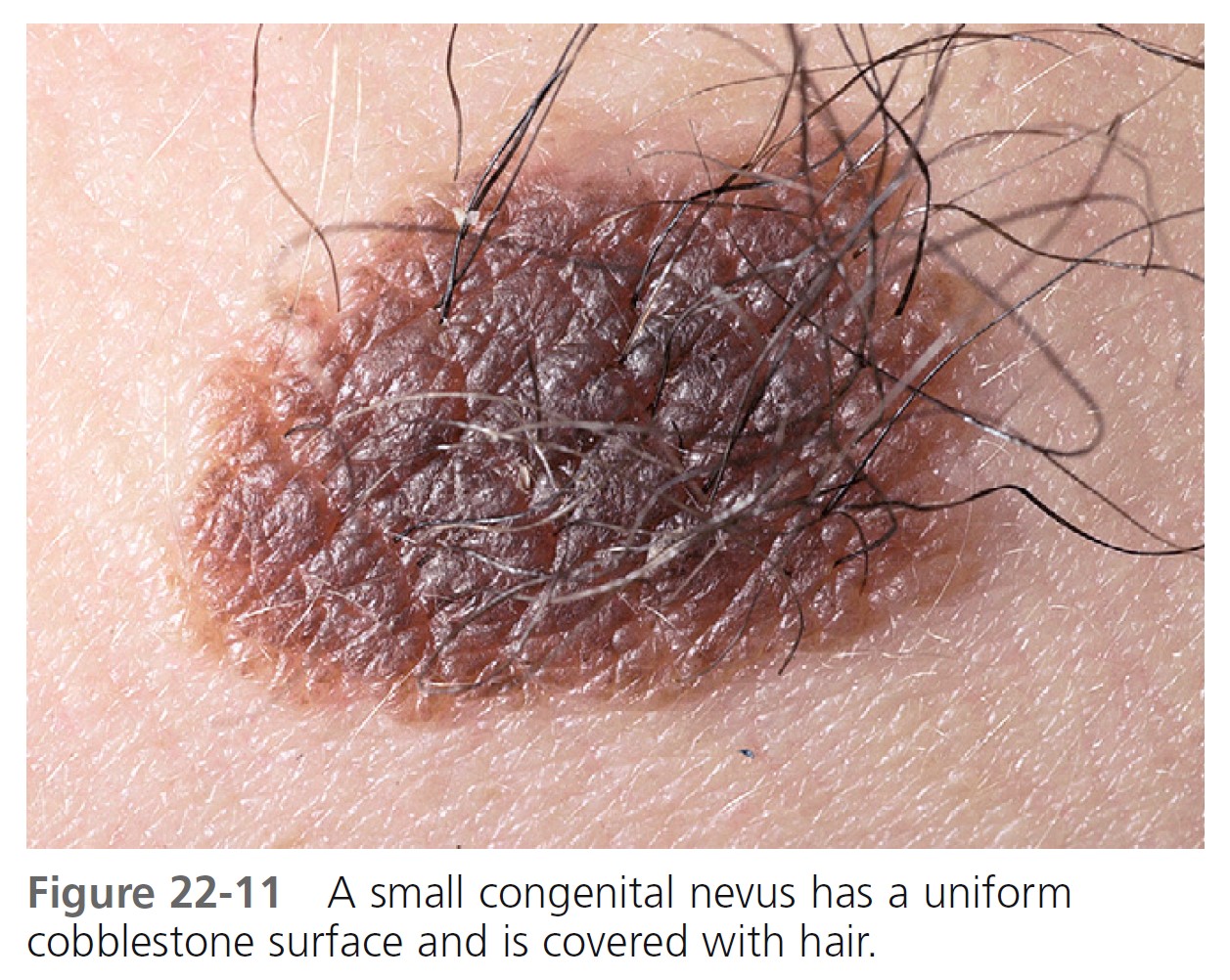

SMALL CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI. The incidence of malignant degeneration in small congenital nevi (<1.5 cm in diameter) is extremely low and prophylactic removal is not essential ( Figure 22-11 ). Almost all melanomas arising in small congenital nevi are of the epidermal variety. Therefore clinical observation will detect malignant changes in small CMNs. If small CMNs are to be excised, delaying this procedure until just before puberty would be appropriate because small congenital nevi do not undergo malignant transformation in prepubertal age groups.

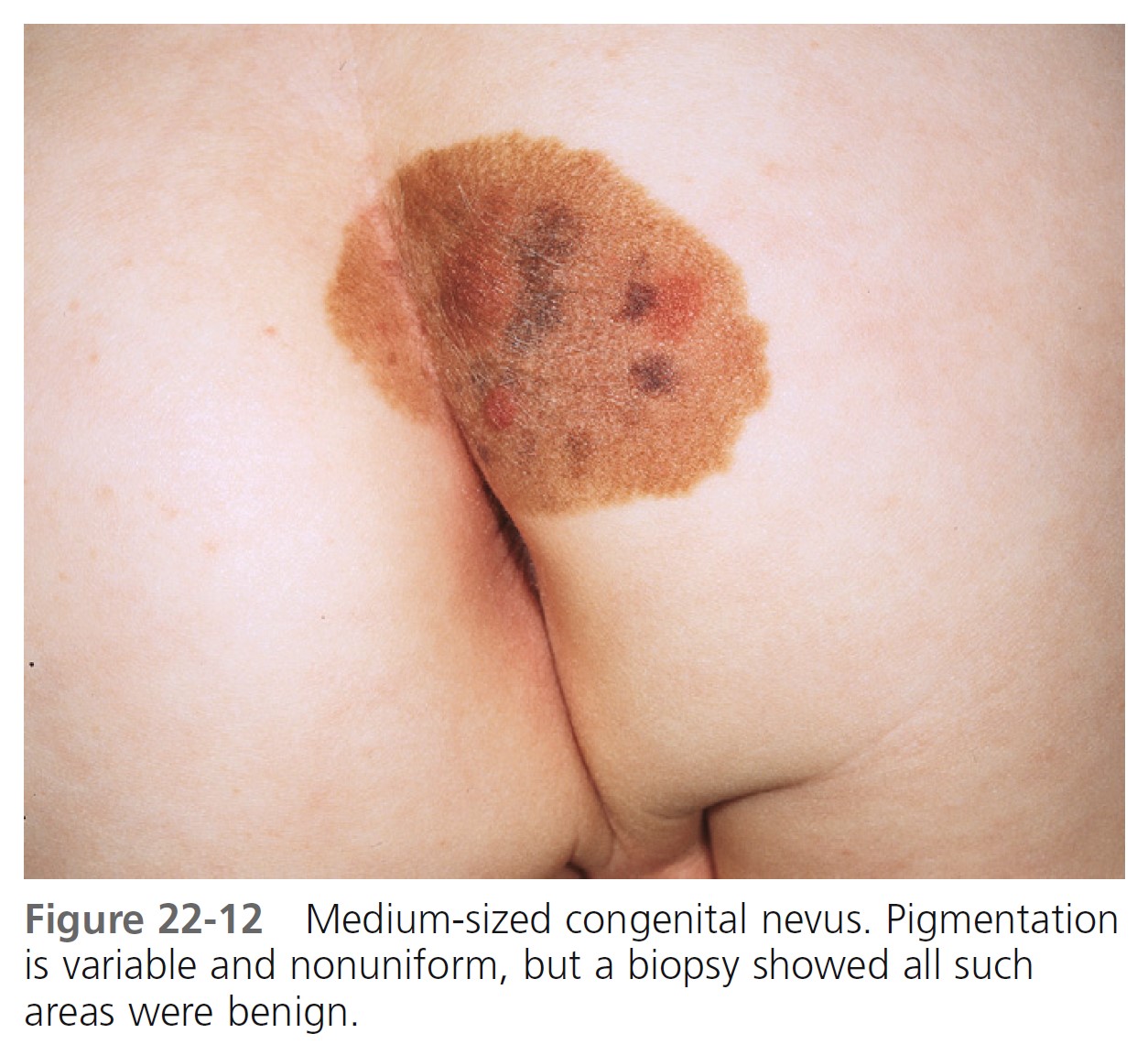

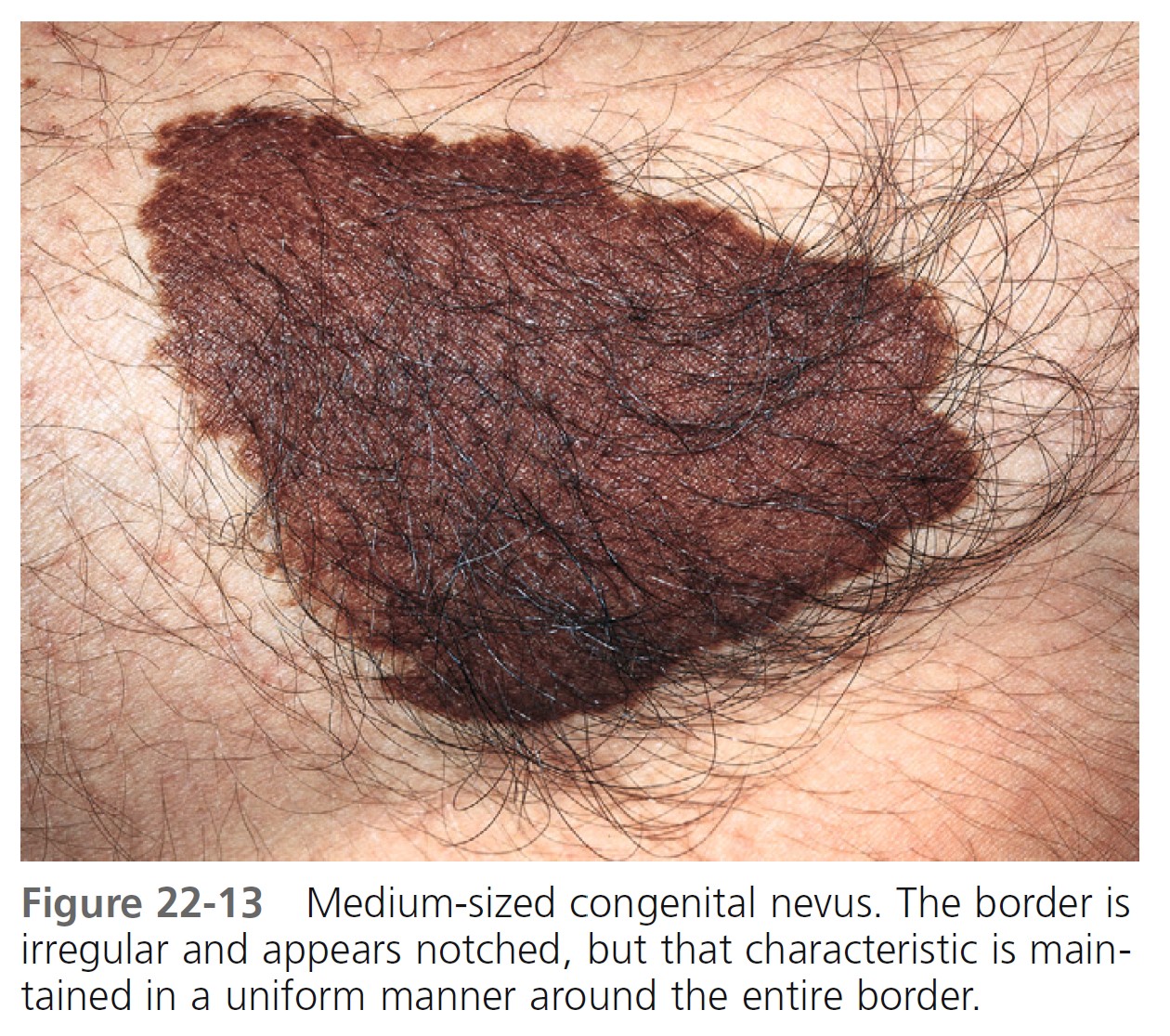

MEDIUM-SIZED CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI. The risk of the occurrence of malignant melanoma in medium-sized (1.5 to 19.9 cm in diameter) congenital melanocytic nevi is the subject of controversy ( Figures 22-12 and 22-13 ). Universally accepted recommendations regarding the management of such lesions have not been made. A short-term follow-up study showed no increased risk for malignant melanoma arising in banal-appearing medium-sized lesions or that prophylactic excision of all such lesions is mandatory. Lifelong medical observation seems a reasonable alternative for many medium-sized CMNs.

Another approach would be to perform a punch or small incisional biopsy. If the histologic pattern is that of an acquired nevus (superficial variant of congenital nevi), then the malignant potential is extremely low, and any malignant transformation would most likely be of the epidermal variety, which would be detectable by clinical observation. If the histologic pattern is that of the deeper dermal tumor, then a significant risk may be present; prophylactic excision at the earliest stage possible would be indicated.

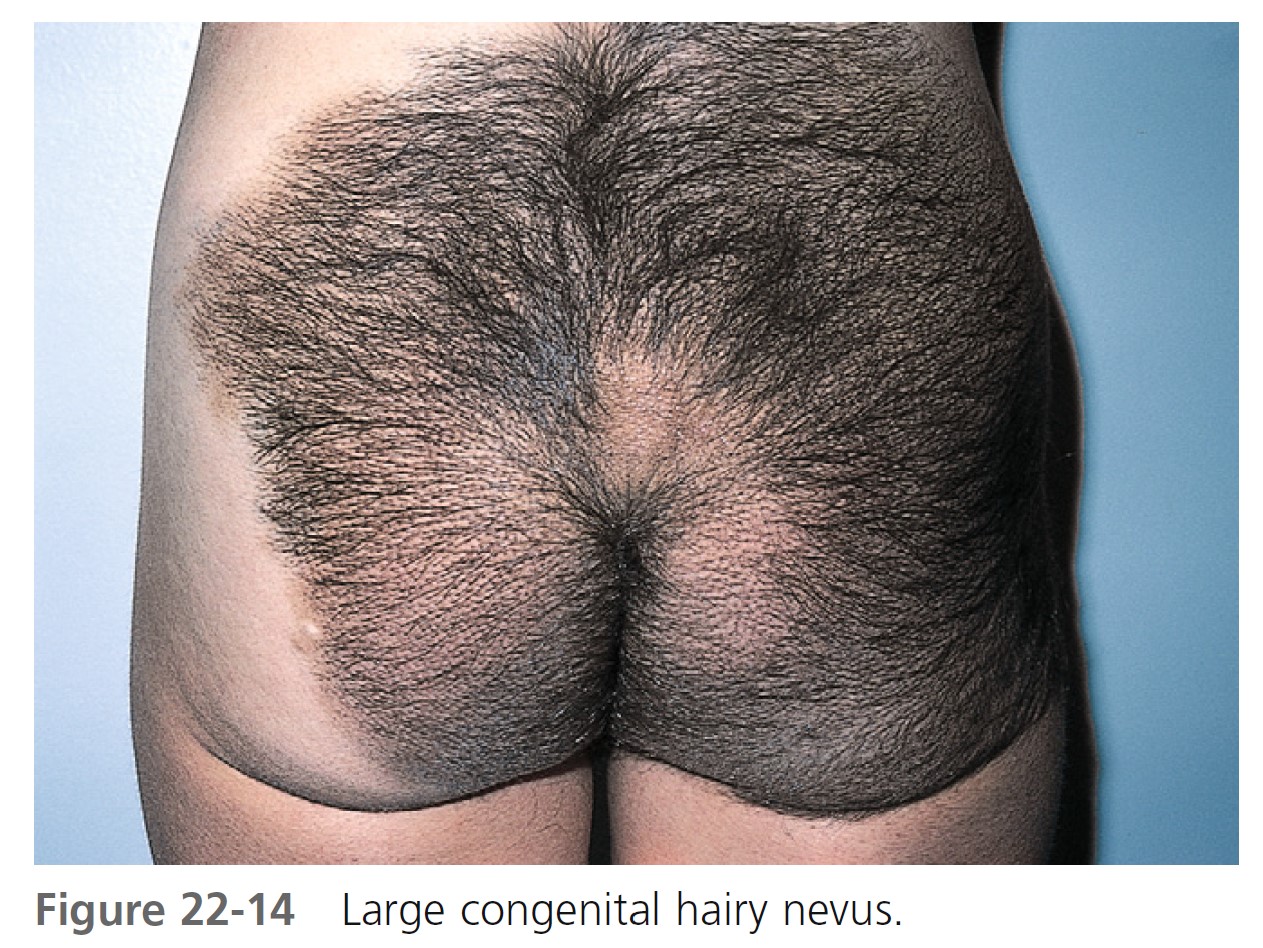

LARGE CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI. Large congenital melanocytic nevi (comprising ≥5% body surface area in preadolescents and >20 cm in adolescents and adults) may undergo malignant transformation ( Figures 22-14 and 22-15 ). The incidence ranges from 1.8% to 7.1%. Approximately half of the melanomas occur by 3 to 5 years of age. Therefore large, thick lesions should be removed as soon as possible. Large CMNs lighten with time and most nodules occur before the age of 2 years. There is an initial darkening with a subsequent significant lightening with age accompanied by increased surface irregularities, nodules, and hair growth. The most common anatomic site is the trunk. Most are associated with satellite congenital nevi, which can be extensive and involve a variety of sites. As many as two thirds of melanomas developing in giant CMNs have nonepidermal origins and are deeper in the dermis or lower subcutaneous tissue. Therefore clinical observation will fail to detect most malignant transformations in these patients.

DERMOSCOPY OF CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI. The most commonly observed dermoscopic features are globules (79.7%), reticular networks (70.3%), hypertrichosis (68.9%), milia-like cysts (52.7%), and perifollicular hypopigmentation (32.4%). PMID: 17709659

NEUROCUTANEOUS MELANOCYTOSIS (NCM). Patients with large CMNs are at risk for NCM, where the leptomeninges contain excessive amounts of melanocytes and melanin. Central nervous system melanomas may occur from malignant degeneration of these melanocytes. Benign proliferation of melanocytes in the leptomeninges may result in complications or death. Patients at greatest risk for developing NCM are those with large CMNs found on the back, head, or neck. Large CMNs of the trunk are associated with a symptomatic NCM occurrence of 4.8%, and an overall mortality from NCM and cutaneous melanoma of 2.3%. If symptomatic NCM developed in those with truncal nevi, however, the occurrence of death rises to 34%. PMID: 16635656 Patients with >20 satellite melanocytic nevi are at greatest risk of developing NCM. Most patients with large CMNs have multiple satellite nevi but no melanoma has ever been reported in satellite nevi.

MANAGEMENT OF CONGENITAL MELANOCYTIC NEVI. Risk assessment and treatment options are considered for each patient. Medical and psychosocial concerns need to be discussed. Management goals are to decrease the risk for developing melanoma by surgical removal and producing good cosmetic results. Removal of a small CMN, with a low risk for developing melanoma, may result in a disfiguring scar and would not be acceptable. Removal of a large, thick CMN that leaves a large, dense scar may be acceptable. Timing of surgery is a consideration. The best surgical scars result from surgery performed early in life; however, it may be best to delay surgery until after age 2 when the full extent of the nevus is evident. Very large lesions may require multiple procedures. CMNs should be removed down to the fascial layer.

PROPHYLACTIC TREATMENT. Prophylactic removal is considered for thick lesions in which it is difficult to detect melanoma. Dense nevi with a wrinkled (rugous) surface have the greatest risk. Growths that appear in covered areas (e.g., scalp, medial buttocks, perianal, genital areas) that are difficult to examine and follow are considered for early excision.

SPECKLED LENTIGINOUS NEVUS. Speckled lentiginous nevus (nevus spilus) is a common hairless, oval or irregularly shaped brown lesion that is dotted with darker brown-to-black spots. They may appear at any age. Lesions can appear at birth or in early infancy as lightly colored café-au-lait macules. Pigmented macules and papules then develop over a period of months to years. Lesions may be very large. It has been suggested that speckled lentiginous nevus is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus. The brown area is usually flat, and the black dots may be slightly elevated and contain typical nevus cells ( Figure 22-16 ). The spots range from 1 to 3 mm in diameter and may be lentigines, junctional, compound, or intradermal nevi. The background hyperpigmentation histologically has the features of a lentigo or café-au-lait macule. There is considerable variation in size, ranging from 1 to 20 cm. The anatomic position or time of onset is not related to sun exposure. Transformation into melanoma is rare. The risk of transformation may be similar to that for classic congenital nevi of similar size. Examine lesions periodically and educate the patient regarding the clinical signs of melanoma. Routine excision is not necessary. Biopsy suspicious areas. Speckled lentiginous nevus is flat and necessitates excision and closure if the patient desires removal. Lasers have been used to treat both the background hyperpigmentation and the speckles of speckled lentiginous nevi.

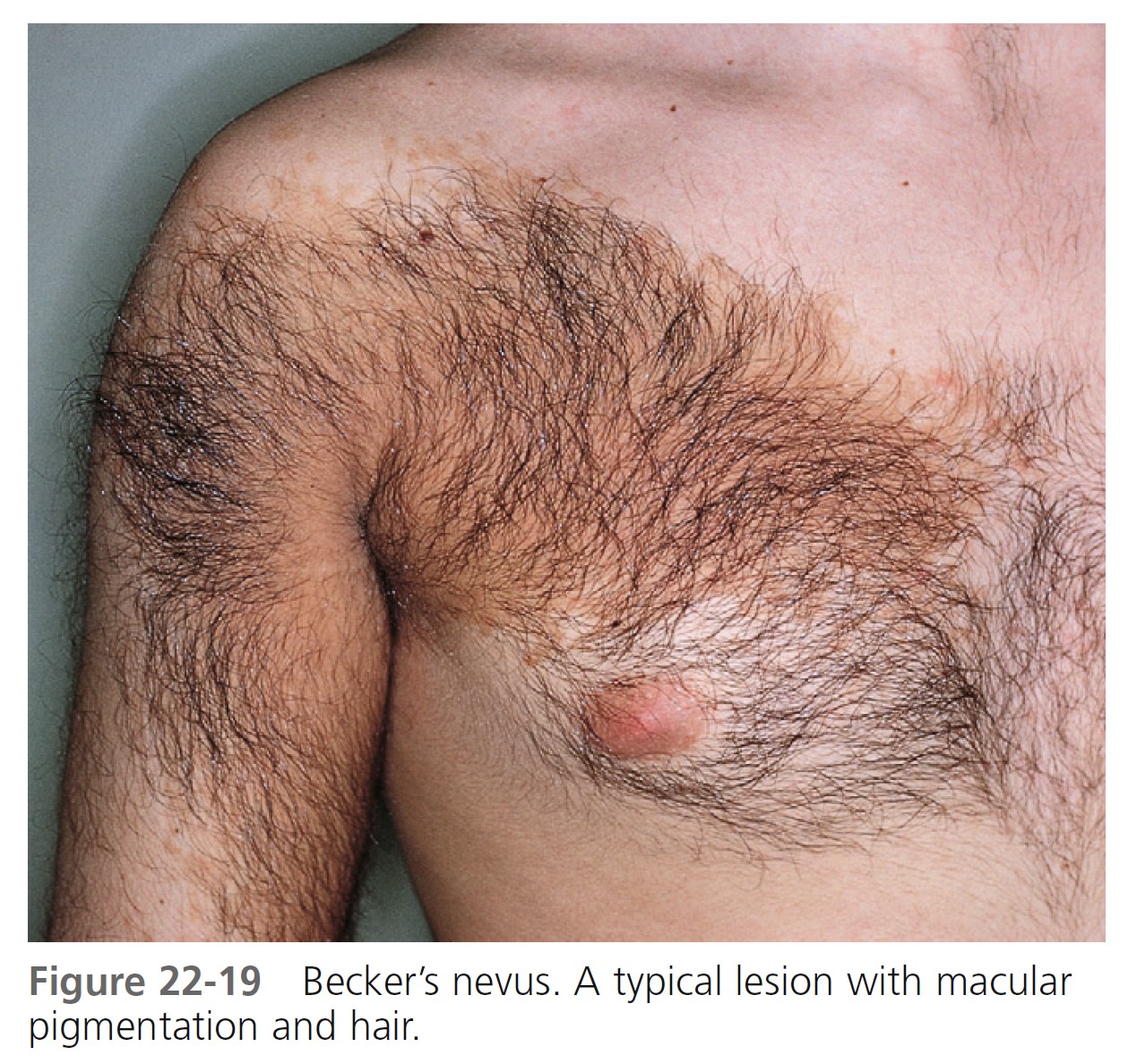

BECKER’S NEVUS. Becker’s nevus is not a nevocellular nevus because it lacks nevus cells. The lesion is a developmental anomaly consisting of either a brown macule ( Figure 22-17 ), a patch of hair ( Figure 22-18 ), or both ( Figure 22-19 ). Nonhairy lesions may later develop hair. The lesions appear in adolescent men on the shoulder, submammary area, and upper and lower back; they rarely appear on the lower limbs. Becker’s nevus varies in size and may enlarge to cover the entire upper arm or shoulder. The border is irregular and sharply demarcated. Malignancy has never been reported.

Becker’s nevus syndrome is the presence of an epithelial nevus showing hyperpigmentation, increased hairiness, and hamartomatous augmentation of smooth muscle fibers as well as other developmental defects such as ipsilateral hypoplasia of the breast and skeletal anomalies, including scoliosis, spina bifida occulta, or ipsilateral hypoplasia of a limb. The Becker’s nevus syndrome usually occurs sporadically.

Dermoscopic features of Becker’s nevus include network, focal hypopigmentation, skin furrow hypopigmentation, hair follicles, perifollicular hypopigmentation, and vessels.

Becker’s nevus is usually too large to remove by excision. The hair may be shaved or permanently removed. Laser removal of hair and pigmentation is reported.

HALO NEVI. A compound or dermal nevus that develops a white border is called a halo nevus. The incidence in the population is estimated to be 1%. Halo nevi are found most commonly in children. The average age of onset is 15 years. The depigmented halo is symmetric and round or oval with a sharply demarcated border ( Figure 22-20 ). There are no melanocytes in the halo area. Halo nevi have the dermoscopic features of benign melanocytic nevi, with globular and/or homogeneous patterns that are typically observed in children and young adults. Halo nevi structural patterns remain unchanged over time. Patients with Turner’s syndrome (short stature, gonadal dysgenesis, webbed neck, cubitus valgus, and lymphedema at birth) have a halo nevus prevalence of 18%. PMID: 15337976

HISTOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS. T lymphocytes at the site of depigmentation suggest that these cells participate in the halo phenomenon. Most halo nevi are located on the trunk; they never occur on palms and soles. They may occur as an isolated phenomenon, or several nevi may spontaneously develop halos. Halos may repigment with time, or the nevus may disappear. Repigmentation often takes place over months or years; however, it does not always occur. Repigmentation does not follow removal of the nevus. The incidence of vitiligo may be increased in patients with halo nevi. A halo may rarely develop around malignant melanoma, but in such instances it is usually not symmetric.

Removal of a halo nevus is unnecessary unless the nevus has atypical features. Parental concern over this impressive change is often reason for a conservative excision. In such cases, the mole part of a halo nevus may be removed by shave, excision, or laser.

SPITZ NEVUS. Spitz nevus (benign juvenile melanoma) is most common in children but does appear in adults. The term melanoma is used because the clinical and histologic appearance is similar to that of melanoma. They are hairless, red or reddish-brown, dome-shaped papules or nodules with a smooth ( Figure 22-21 ) or warty surface; they vary in size from 0.3 to 1.5 cm. The color is caused by increased vascularity, and bleeding sometimes follows trauma. Spitz nevi are usually solitary but may be multiple. They appear suddenly and, contrary to slowly evolving common moles, patients can sometimes date their onset. The Spitz nevus should be removed for microscopic examination. Histologic differentiation from melanoma is sometimes difficult. Dermoscopy of Spitz nevus shows (1) a starburst pattern, characterized by a prominent, black to blue diffuse pigmentation and pseudopods regularly distributed at the periphery in a radiate pattern; and (2) a globular pattern, typified by a discrete, brown to gray-blue pigmentation and a peripheral rim of large brown globules, often extending throughout the entire lesion.

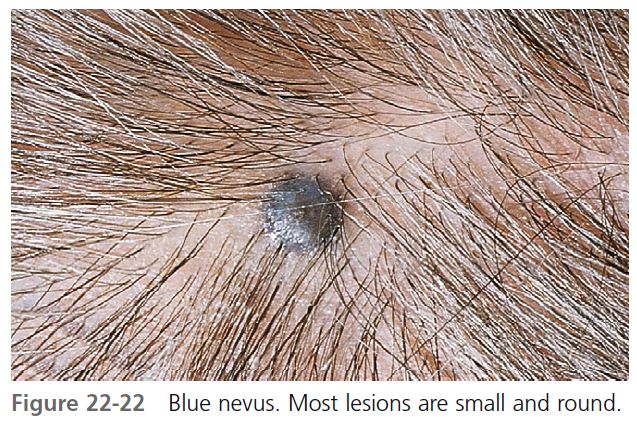

BLUE NEVUS. The blue nevus is a slightly elevated, round, regular nevus, usually less than 0.5 cm, and contains large amounts of pigment located in the dermis ( Figure 22-22 ). The brown pigment absorbs the longer wavelengths of light and scatters blue light (Tyndall effect). The blue nevus appears in childhood and is most common on the extremities and dorsum of the hands. A rare variant, the cellular blue nevus, is larger (usually greater than 1 cm) and nodular and is frequently located on the buttocks.

Melanomas are reported as arising in association with a common or cellular blue nevus and arising de novo and resembling cellular blue nevi. Blue nevi may be removed for cosmetic purposes.

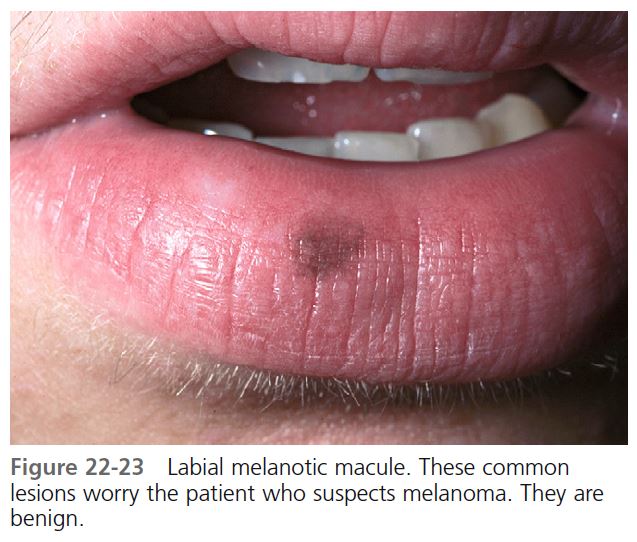

LABIAL MELANOTIC MACULE. Brown macules on the lower lip are relatively common, especially in young adult women ( Figure 22-23 ). Histologically, they resemble freckles and not lentigo, but unlike freckles, they do not darken with sun exposure. They are benign. Cryotherapy or laser surgery is used for patients who request treatment.

Atypical nevi

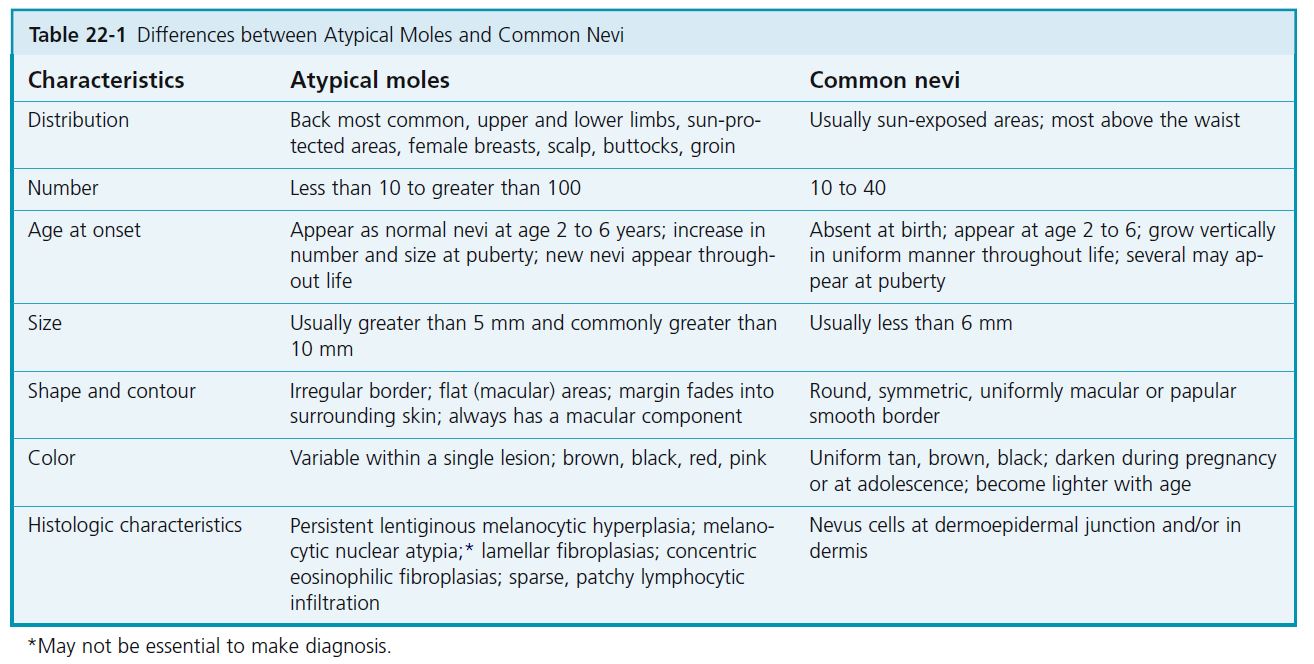

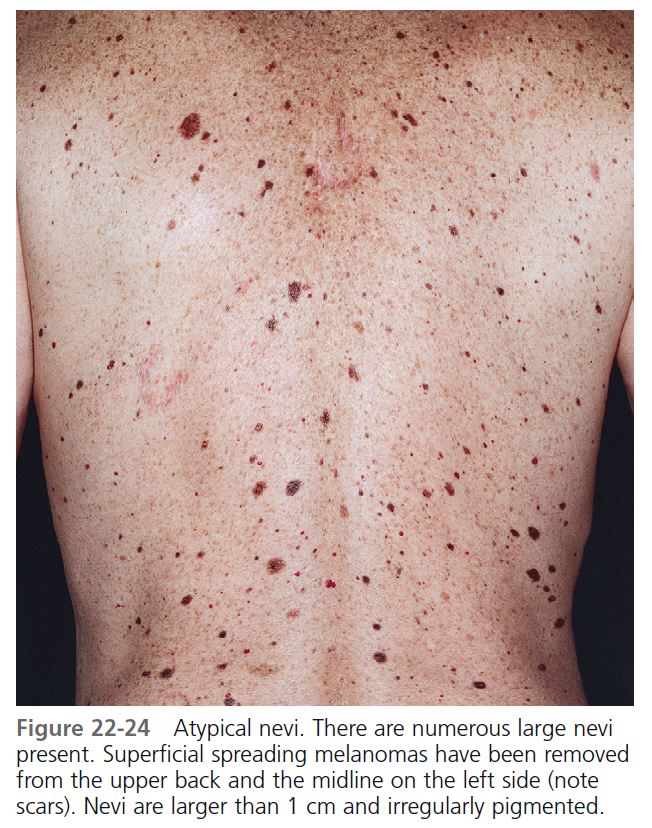

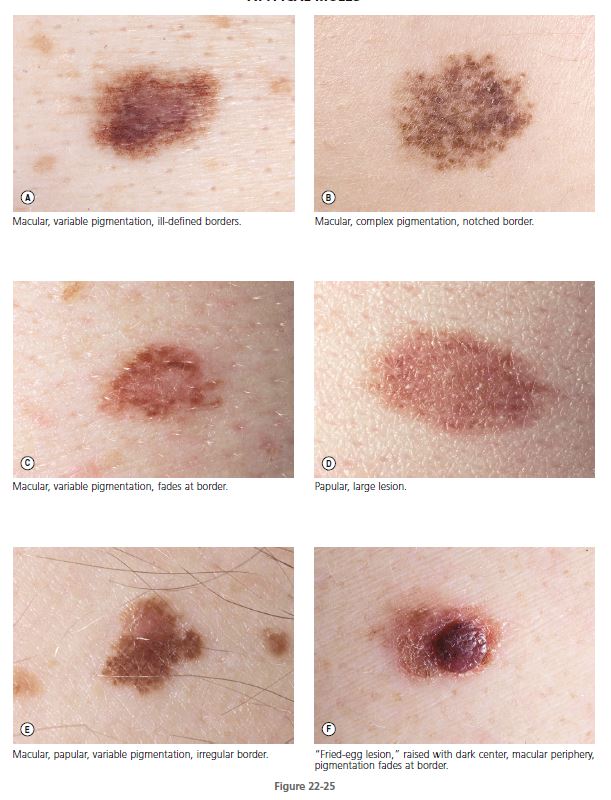

Atypical nevi, also referred to as dysplastic nevi or Clark nevi, may be inherited in a familial pattern or occur sporadically. They are usually larger than 5 mm in diameter and are either flat or flat with a raised center (“fried-egg lesion”) ( Table 22-1 ). They are darkly or irregularly pigmented with shades of brown and pink and usually have irregular or indistinct borders. Dysplastic nevi are common, with a prevalence rate of about 5%. Dysplastic nevi differ from common acquired nevi by (1) beginning to appear near puberty instead of in childhood and (2) continuing to develop past the fourth decade. Atypical nevi are a “marker” for patients at an increased risk for development of melanoma and a precursor lesion to melanoma. No data are available to assess what effect prophylactic removal has on decreasing the risk for future development of melanoma.

FAMILIAL MELANOMA AND MELANOMA PRECURSORS. Cutaneous melanoma may occur as isolated, so-called sporadic cases; in association with multiple atypical nevi; or in familial clusters, in which case it is referred to as the atypical mole syndrome (AMS), formerly known as dysplastic nevus syndrome. In the late 1970s the dysplastic nevus (DN) or atypical mole (AM) was identified in melanoma-prone families. It was then determined that AMs are cutaneous markers that identify specific family members who are at increased risk for melanoma. The AM may also be the single most important precursor lesion of melanoma. These nevi may occur in persons from melanoma-prone families and in persons who lack both a family history and a personal history of melanoma.

ATYPICAL MOLE SYNDROME AND FAMILIAL MELANOMA. Numerous families with multiple melanoma patients have been reported. These patients usually develop melanoma at a young age, have a predisposition to multiple primary melanomas, and have the tendency to develop thin, superficial-spreading melanomas. Large, unusual-looking moles were initially recognized as a precursor to melanoma in patients with familial cutaneous melanoma. This syndrome was named B-K mole syndrome from two of the probands, and the precursor nevi were designated as B-K moles and later referred to as dysplastic nevi (DN). The syndrome is now called the atypical mole syndrome (AMS). Recent estimates suggest that approximately 32,000 persons in the United States have familial AMS with familial melanoma, accounting for approximately 5.5% of all melanomas diagnosed in this country. Hereditary malignant melanoma and atypical moles represent pleiotropic effects of a mendelian autosomal dominant gene with high penetrance.

One study showed that the hereditary cutaneous malignant melanoma/AMS does not predispose to other cancers.

DEFINITION. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Conference on Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Melanoma has defined the familial atypical mole and melanoma syndrome as (1) the occurrence of malignant melanoma in one or more first- or second-degree relatives; (2) a large number of melanocytic nevi (MN), often more than 50, some of which are atypical and often variable in size; and (3) melanocytic nevi that demonstrate certain histologic features. AMS probably represents a spectrum. At one end all members of a kindred have atypical moles (AMs) and some have malignant melanoma (MM). At the other end are persons with one AM without a personal or family history of MM.

ASSOCIATION WITH MELANOMA. Patients with AMS, familial or sporadic, are at significant risk for developing melanoma. Atypical moles have been observed in 8% of patients with nonfamilial (sporadic) melanoma, and the transformation into superficial-spreading melanoma has been photographically documented. Family members without atypical moles do not show any apparent increase in melanoma risk. The frequency of sporadic AMS in the general population is unknown.

Atypical moles are found on the skin of 90% of patients with hereditary melanomas, and more than 50% of melanomas in this group are associated histologically with and probably evolve from atypical moles. The lifetime risk of developing cutaneous melanoma among the white population in the United States is approximately 0.8%; that is, 1 in 125 persons who have AMS and no family members with the disease have a 6% risk of developing melanoma. Persons who have AMS and a history of melanoma have a 10% risk of getting a second melanoma; persons who have AMS and have a family member with melanoma have a 15% risk. The lifetime risk of melanoma approaches 100% for those people with AMS from families with two or more first-degree relatives who have cutaneous melanoma.

Among atypical mole-bearing family members, those patients with melanoma have very large numbers of nevi more frequently than patients with AMS without melanoma. Family members with AMS have more nevi than do patients who have only common acquired types of nevi.

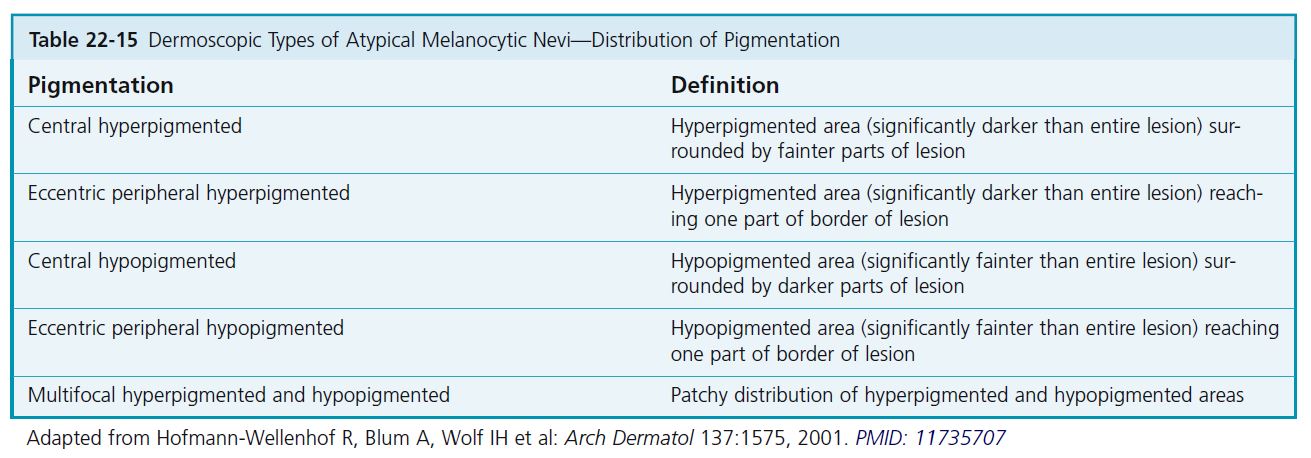

Classification of atypical melanocytic nevi

CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION

The clinical diagnosis of atypical melanocytic nevi is established when at least three of the following characteristics are present:

• Diameter greater than 5 mm

• Ill-defined borders

• Irregular margin

• Varying shades in the lesion

• Presence of papular and macular components

CLINICAL FEATURES OF ATYPICAL MOLES

MORPHOLOGY. These unusual nevi differ in a number of important ways from typical acquired pigmented nevi or moles (see Table 22-1 ). Atypical moles are larger than common moles. They have a mixture of colors, including tan, brown, pink, and black. The border is irregular and indistinct and often fades into the surrounding skin. The surface is complex and variable, with both macular and papular components ( Figure 22-24 ). A characteristic presentation is a pigmented papule surrounded by a macular collar of pigmentation (“fried-egg lesion”) ( Figure 22-25 ). In one study, the total number of nevi and macular components were the only useful features to predict histologic melanocytic dysplasia. However, “fried-egg lesions” often do not display histologic melanocytic dysplasia. In contrast, the absence of a macular component in melanocytic nevi in a person with fewer than 13 total body nevi accurately predicts the absence of melanocytic dysplasia on histologic examination.

SURFACE CHARACTERISTICS. The surface characteristics of atypical nevi are distinctive and can be appreciated with a hand lens and dermoscope (see Figure 22-46 ).

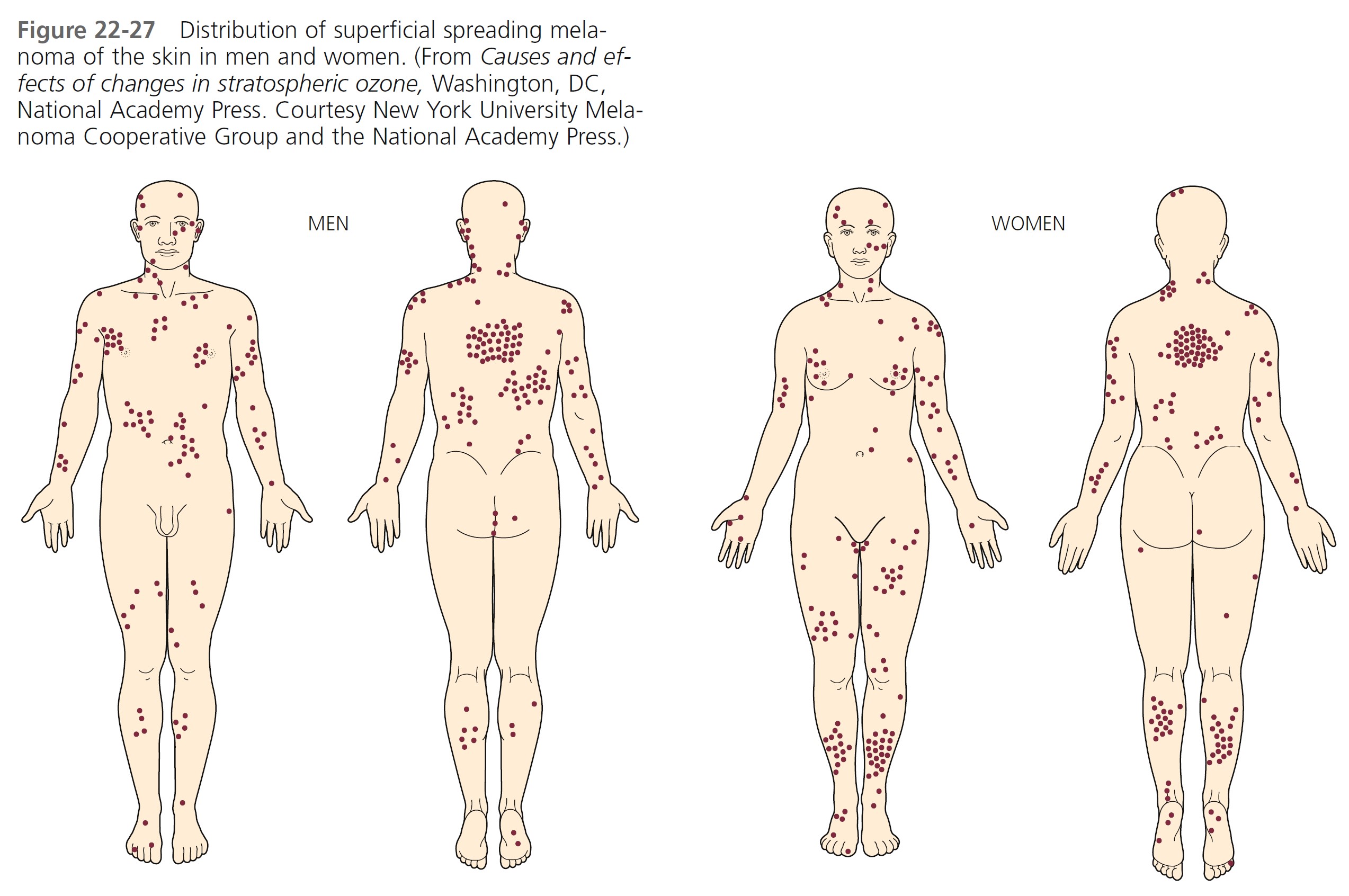

DEVELOPMENT AND DISTRIBUTION. Atypical moles (AMs) are not present at birth, but begin to appear in the mid-childhood years as typical common moles. The appearance changes at puberty, and newer lesions continue to appear well after the age of 40. Common moles occur most often on sun-exposed areas. AMs occur in those locations and at unusual sites such as the scalp, buttocks, and breast. The predilection sites for melanoma in familial AMs patients of both genders correspond with the distribution of nevi; in males, nevi and melanoma counts are higher on the back; in females, both the back and the lower extremities are affected. These findings strongly suggest an association between nevus distribution and melanoma occurrence and site in familial AMs.

HISTOLOGIC CHARACTERISTICS. The NIH Consensus Conference listed the histologic criteria as follows: architectural disorder with asymmetry, subepidermal (concentric eosinophilic and/or lamellar) fibroplasia, and lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia with spindle or epithelioid melanocytes aggregating in nests of variable size and forming bridges between adjacent rete ridges. Melanocytic atypia may be present to a variable degree. In addition, there may be dermal infiltration with lymphocytes, as well as the “shoulder” phenomenon (intraepidermal melanocytes extending singly or in nests beyond the main dermal component).

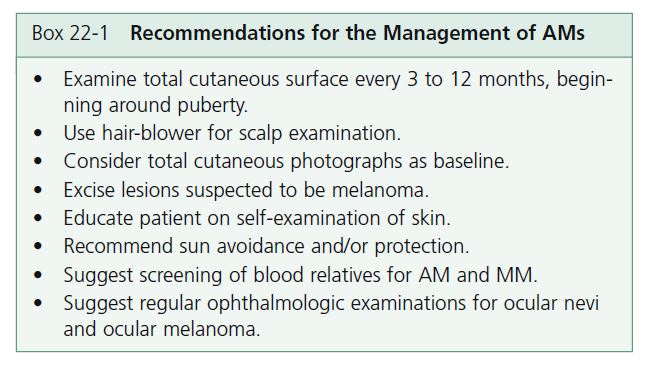

MANAGEMENT. Recommendations for treatment of patients with AMs have been given in the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement, October 24 to 26, 1983. These, along with other recommendations, are given in Box 22-1 .

MALIGNANT MELANOMA

Malignant melanoma is a malignancy of melanocytes that occurs in the skin, eyes, ears, gastrointestinal tract, leptomeninges, and oral and genital mucous membranes. One of the most dangerous tumors, melanoma has the ability to metastasize to any organ, including the brain and heart.

EPIDEMIOLOGY. In the United States, melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in men and the sixth most common cancer in women. A total of 62,000 cases of melanoma were diagnosed in the United States in 2006.

The incidence of malignant melanoma is increasing rapidly worldwide. Currently, 1 in 63 Americans will develop melanoma during their lifetime; the risk was 1 in 1500 in 1935. The highest incidence is in Australia and New Zealand. The median age at diagnosis is 57 years, and the median age at death is 67 years. Males are approximately 1.5 times more likely to develop melanoma than females. The most common areas are the back for men and the arms and legs for women.

Whites have a 10-fold greater risk of developing cutaneous melanoma than blacks, Asians, or Hispanics. Whites and blacks have a similar risk of developing plantar melanoma. Noncutaneous melanomas (e.g., mucosal) are more common in non-white populations.

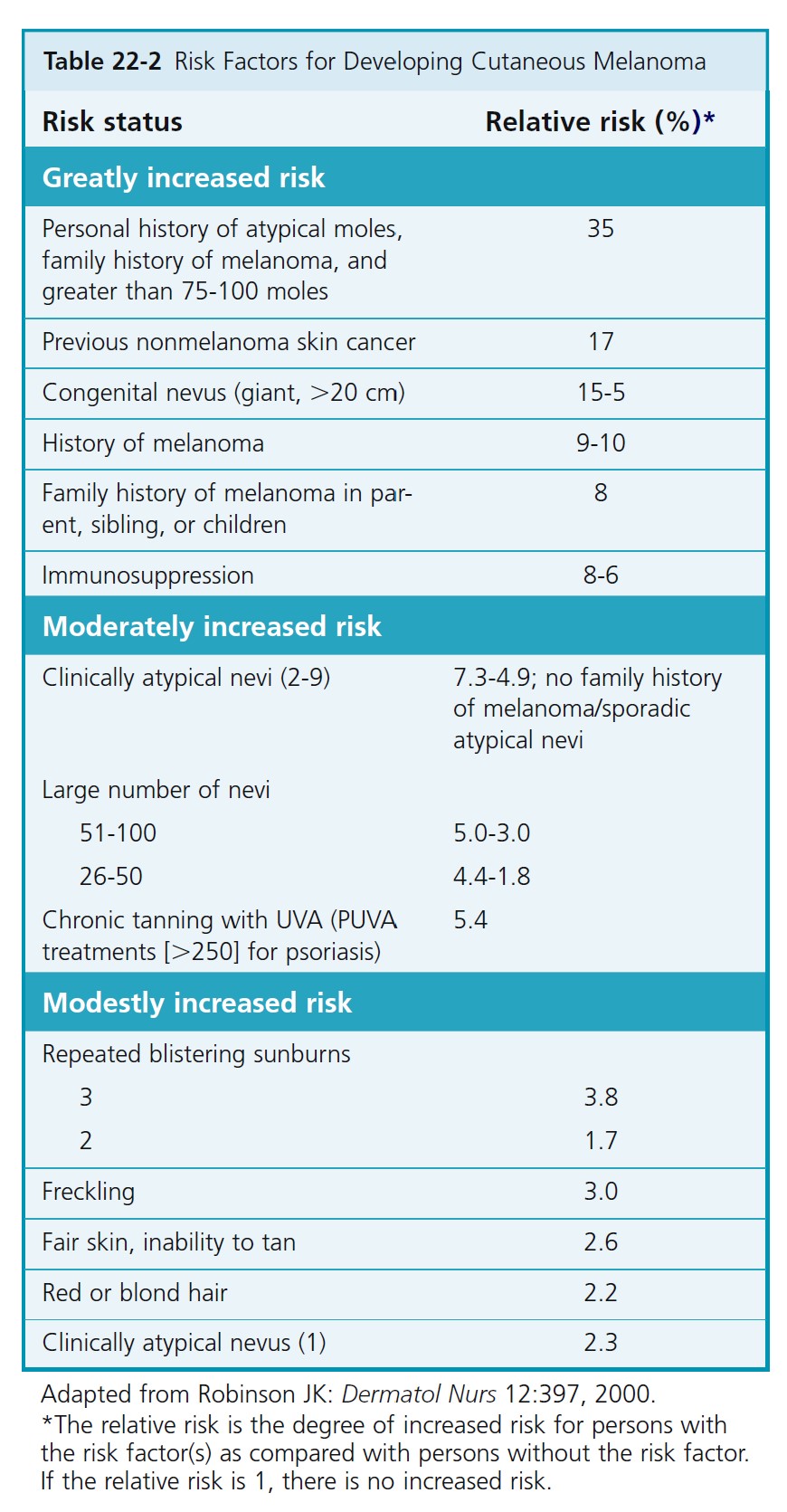

RISK FOR MELANOMA. The risk factors for melanoma are listed in Table 22-2 .

ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION EXPOSURE. Increased exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is considered to be a factor for the increased incidence of melanoma. Sunburns are a risk factor for melanoma. Sunburns are primarily due to UVB (280 to 320 nm) radiation. Melanomas are also increased in people exposed to ultraviolet A (UVA) radiation. High doses of UVA radiation are received in sun beds and with exposure to psoralen and UVA (PUVA) therapy.

PUVA and risk of melanoma. Oral methoxsalen (psoralen) and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) is effective therapy for psoriasis and other skin conditions. It is carcinogenic. An increased risk of melanoma is observed beginning 15 years after first exposure to oral methoxsalen (psoralen) and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA). This risk is greater in patients exposed to high doses of PUVA, appears to be increasing with the passage of time, and should be considered in determining the risks and benefits of this therapy.

RISK AND SUN EXPOSURE. Increased recreational sun exposure and alterations of the upper atmosphere by pollutants that result in increased radiation may be the two most important factors in the disproportionate rise in the incidence of melanoma. People who suntan poorly or sunburn easily or who have had multiple or severe sunburns have a twofold to threefold increased risk for developing cutaneous melanoma. Individuals with recreational and vacation sun exposure who experience acute episodic exposures to sunlight may be at greater risk than those with constant occupational sun exposure. Continuous UV radiation exposure, either in adult life or during adolescence, seems to play a protective role in melanoma risk. Those with outdoor occupations have been found to have a lower risk of acquiring melanoma. Intermittent exposure is associated with significant risk increases of melanoma. It is postulated that sunlight causes cutaneous immunosuppression.

SUNSCREEN EFFECTIVENESS. Chemical sunscreens block UVB but are less effective at blocking UVA, which comprises 90% to 95% of ultraviolet energy in the solar spectrum. Sunscreens prevent erythema and sunburn, but inhibit accommodation of the skin to sunlight; therefore their use may permit excessive exposure of the skin to UVA. Laboratory data suggest that melanoma is promoted by

UVA; therefore UVB sunscreens might not be effective in preventing melanoma. Sunscreen use may give people a false sense of security and encourage excessive exposure. Wearing hats and protective clothing and avoiding sunbathing are more protective than chemical sunscreens. For white, freckled children, the use of a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a high sun protection factor attenuates the development of nevi and, by deduction, decreases the risk of developing a melanoma. Sunscreens that contain zinc oxide or titanium dioxide reflect light and are referred to as physical rather than chemical sunscreens. These compounds effectively block UVA light.

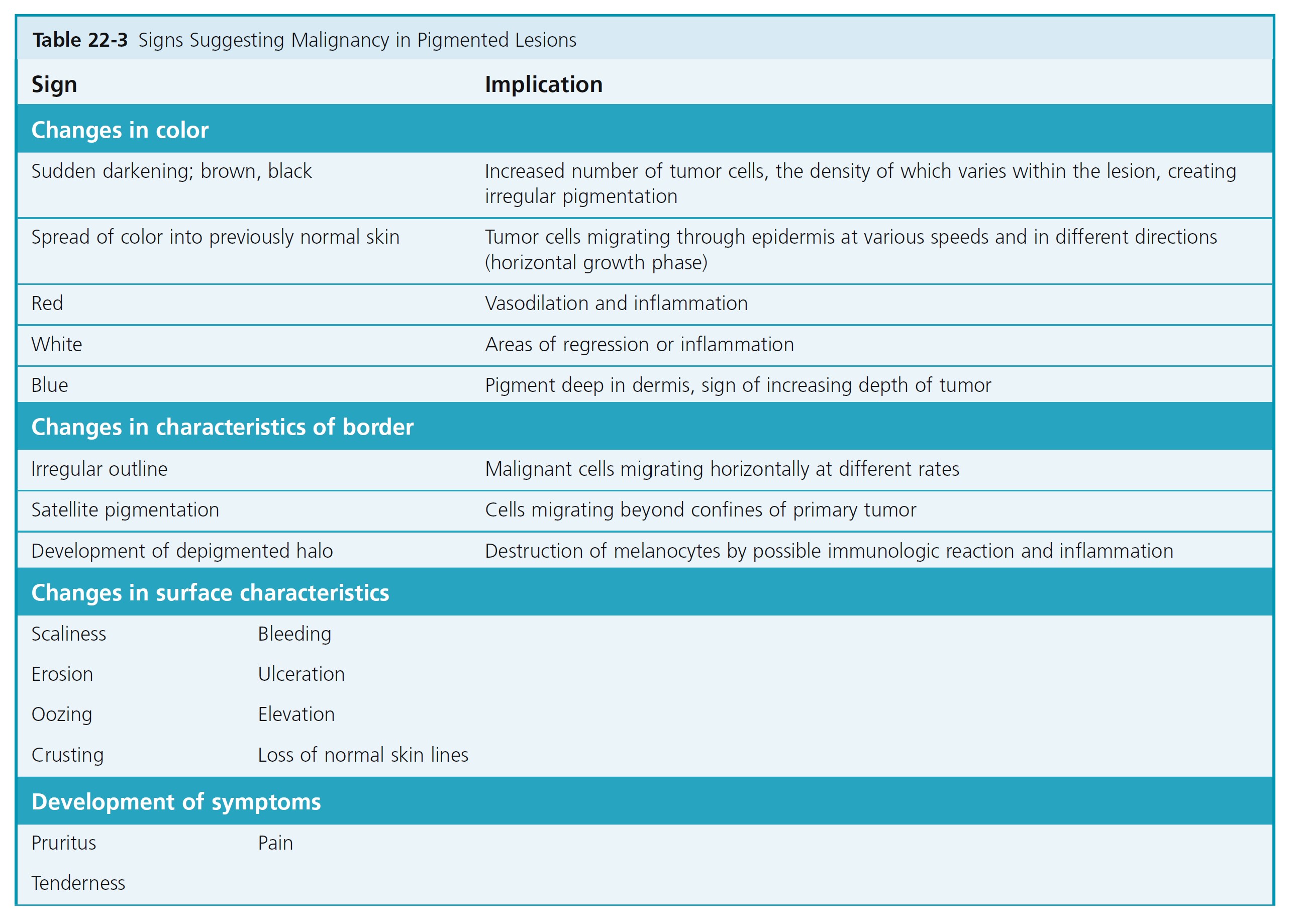

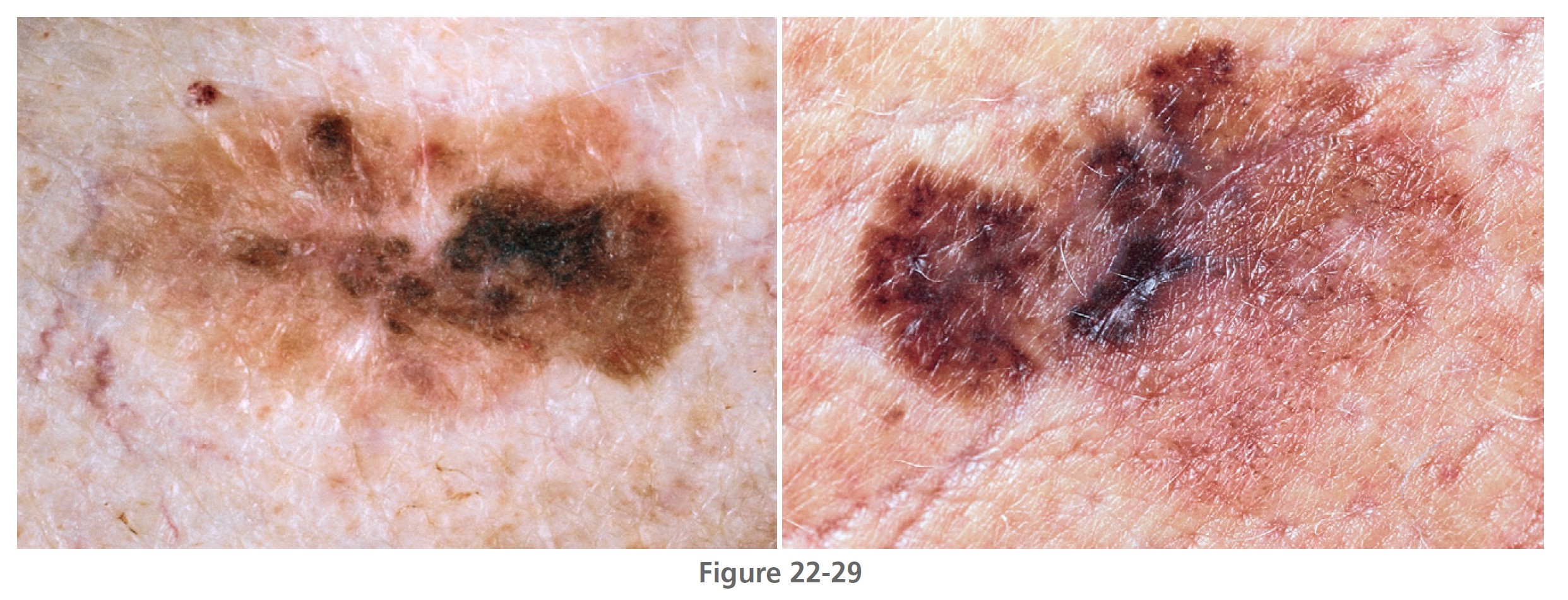

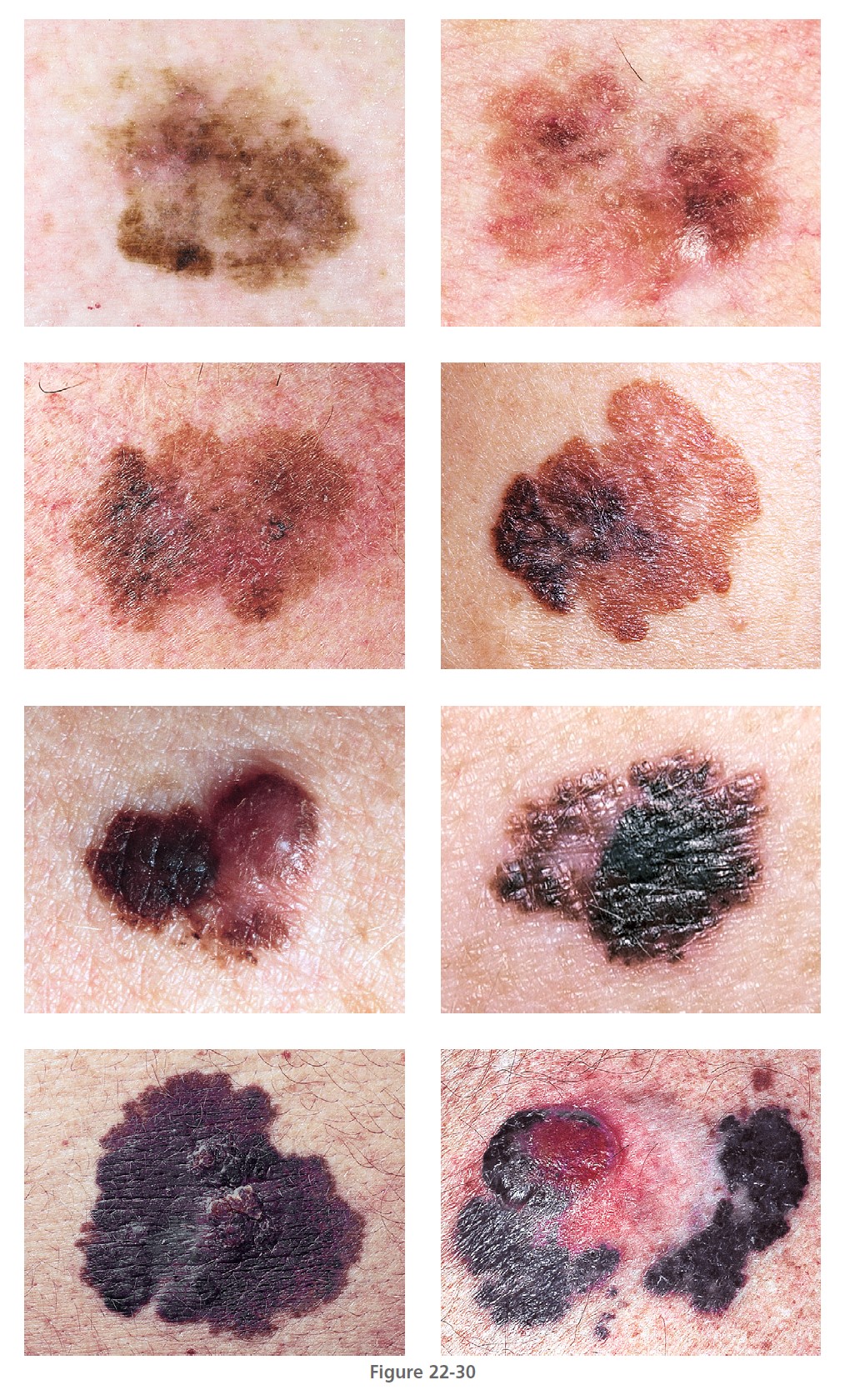

ABCDs OF MALIGNANT MELANOMA RECOGNITION. The goal is to recognize melanomas at the earliest stage. Compared to common acquired melanocytic nevi, malignant melanomas tend to have Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, and Diameter enlargement. Changes in shape and color are important early signs and should always arouse suspicion. Ulceration and bleeding are late signs; hope of cure diminishes greatly if the diagnosis has not been made before such changes occur. The specific signs that appear during the evolution of each type of melanoma are listed and illustrated on the following pages. A list of all possible changes at all stages of development is given in Table 22-3 .

CHARACTERISTICS OF BENIGN MOLES. Moles evolve and change during life. All of the changes occur over long periods of time and are nearly imperceptible. Circumferential enlargement occurs in common nevi of children. Benign acquired nevi progress from lentigo simplex, to flat pigmented junctional nevi, to elevated pigmented compound nevi, to more elevated skin-colored intradermal nevi over decades. Intradermal nevi continue to elevate as collagen is laid down over nests of nevus cells in the upper dermis. Therefore the distance between the dermoepidermal junction and the top of the underlying intradermal nevus increases with age.

Benign moles have a more uniform tan, brown, or black color. The border is regular and the lesion is roughly symmetric; if the lesion could be folded in half, the two halves would superimpose. Most acquired benign moles are 6 mm or less in diameter and appear early in life.

RECENT CHANGE IN A MOLE. The patient’s description of a change in a mole may be the earliest sign of melanoma. Changing color; developing erythematous or hyperpigmented halos; increasing diameter, height, or asymmetry of borders; or changing surface characteristics as well as pruritus, pain, bleeding, ulceration, or tenderness all suggest evolution into melanoma.

PRECURSOR LESIONS

Acquired melanocytic nevi. People with an increased number of benign melanocytic nevi have an increased risk for the development of melanoma. The number at which point the risk becomes significant varies from person to person, depending on factors such as family history and sun exposure. Because 80% of all patients have up to 50 benign nevi, a practical “cut-off” number of nevi over which patients might be at an increased risk for the development of melanoma would be 50. The relative risk for these patients has ranged from 3 to 15 when compared with the relative risk for patients with either no nevi or fewer than five nevi.

Atypical nevi. Atypical nevi may be observed in persons with or without melanoma and may be inherited in a familial pattern or occur sporadically. They are usually larger than 5 mm in diameter and are either flat or flat with a raised center (“fried-egg lesion”). They are darkly or irregularly pigmented with shades of brown and pink and usually have irregular or indistinct borders. Patients with atypical nevi outside of the familial melanoma setting have an increased risk for the development of melanoma but the rate is much lower. One clinically atypical nevus was associated with a 2-fold increased risk for the development of melanoma, whereas 10 or more atypical nevi conferred a 12-fold increased risk over patients without atypical nevi.

Congenital nevi. The malignant potential of congenital nevi is dependent on size and histologic pattern (see p. 851 ).

FOUR MAJOR CLINICAL-HISTOPATHOLOGIC SUBTYPES

Melanoma either begins de novo or develops from a preexisting lesion, such as a congenital or atypical mole. A classification into several different types was devised after observing that the microscopic anatomy of the tumor at the periphery of the elevated tumor mass was variable and possessed characteristic patterns that could be correlated with distinctive clinical presentations. The proposed types are superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM), nodular melanoma (NM), and acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM).

Many, but not all, pathologists recognize these various clinicopathologic types of melanoma. Some melanomas do not conform to this clinicopathologic classification and may be labeled exclusively as malignant melanoma. Malignant melanoma may be a single entity that has various clinical and histologic forms varying with the degree of differentiation of the tumor cell. The potential for a melanocyte to degenerate and become neoplastic is probably influenced by a number of factors, including degree of skin pigmentation, heredity, immunologic status, quantity of solar radiation, gender of the individual, and anatomic position on the body.

GROWTH CHARACTERISTICS. Once a melanocyte becomes neoplastic, constraints on its localization are removed, and it may leave its assigned position at the basal layer of the epidermis. A well-differentiated malignant melanocyte retains its affinity for the epidermis and may grow slowly horizontally, only to be restrained or eliminated in some areas by a still-competent immunologic system. Years of slow growth and regression by a number of such cells on the face produce the LMM.

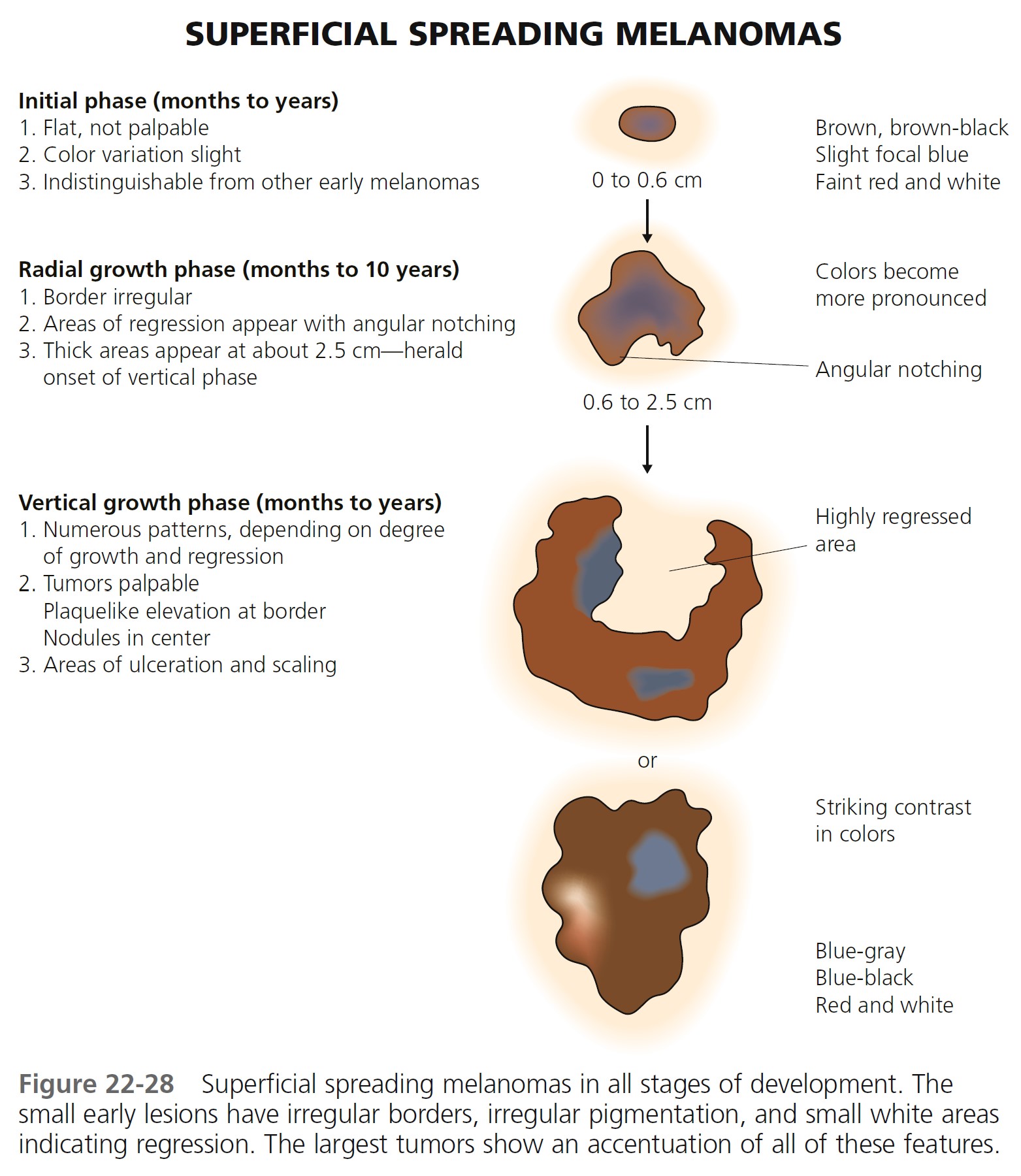

A more immature group of cells would be more aggressive and extend and regress at a faster rate, stimulating new vessel formation and inflammation. Such biologic behavior could be expected to produce the SSM. Melanomas in which the cells are extending laterally are considered to be in the horizontal (radial) growth phase. This phase may endure for months or years.

A poorly differentiated cell knows no bounds, has no affinity for the epidermis, and grows both horizontally and vertically, producing a mass or NM. Melanomas in which cells have begun to grow vertically into the dermis and form a mass are considered to be in the vertical growth phase. The validity of the type classification has yet to be settled; however, it does enable one to understand

the growth and evolution of malignant melanoma; and therefore is an aid to making an early diagnosis.

The various types of melanomas have specific characteristics.

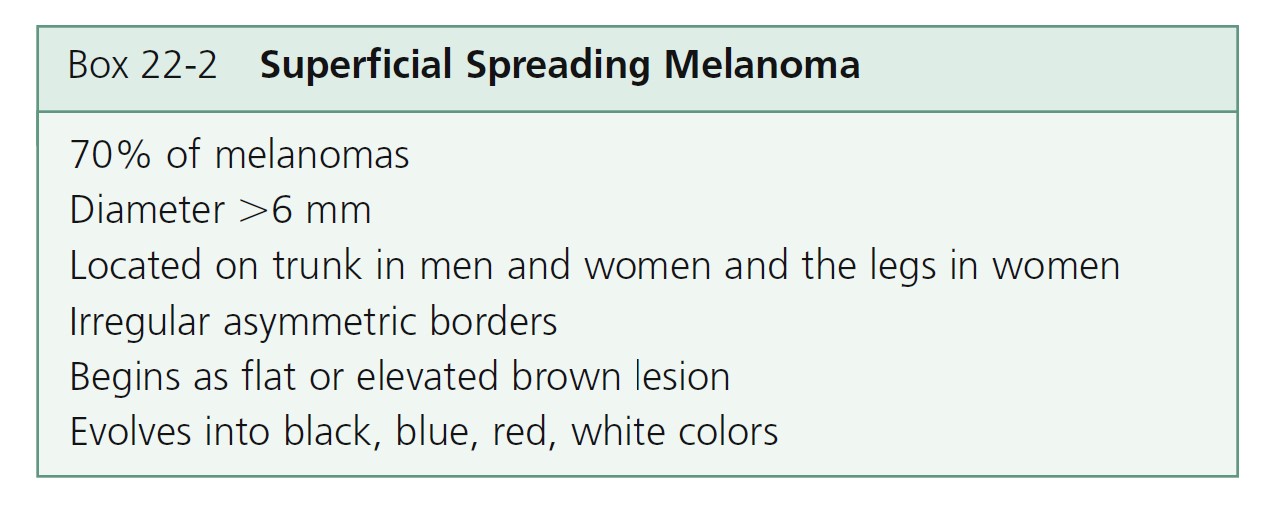

Superficial spreading melanoma

Superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) ( Box 22-2 ) is most common in middle age, from the fourth to fifth decade. It develops anywhere on the body, but most frequently on the upper back of both genders and on the legs of women ( Figures 22-26 to 22-30 ). SSM begins in a nonspecific manner and then changes shape by radial spread and regression (see Figure 22-28 ). The random migration of cells, along with the process of regression, results in lesions with an endless variety of shapes and sizes. The shape is bizarre if left untreated for years. The hallmark of SSM is the haphazard combination of many colors, but it may be uniformly brown or black. Colors may become more diverse as time proceeds. A dull red color is frequently observed, which may occupy a small area or may dominate the lesion. The precursor radial growth phase may last for months or for more than 10 years. Nodules appear when the lesion is approximately 2.5 cm in diameter.

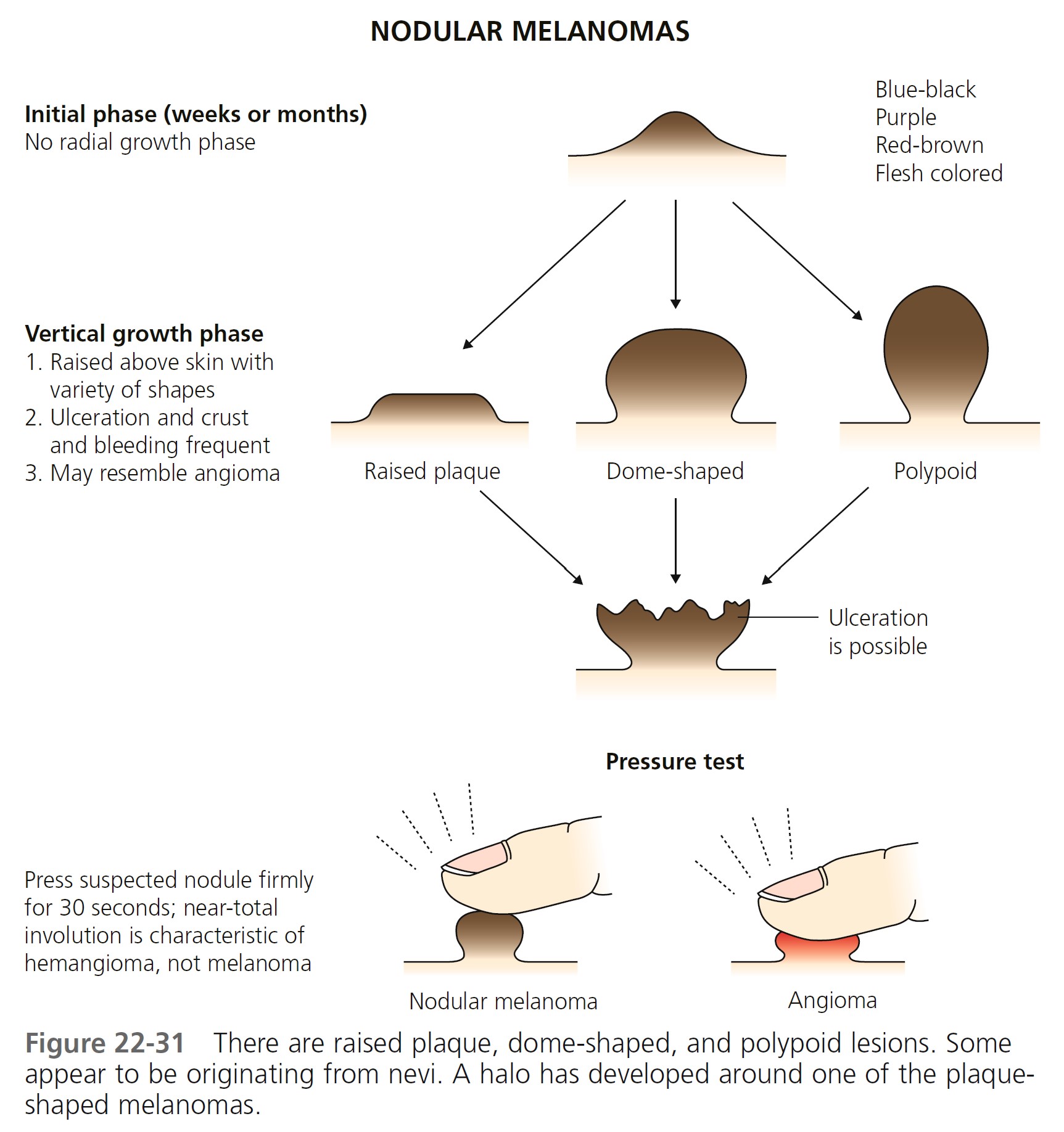

Nodular melanoma

Nodular melanoma (NM) ( Figures 22-31 and 22-32 , Box 22-3 ) occurs most often in the fifth or sixth decade. It is more frequent in males than females, with a ratio of 2:1. It is found anywhere on the body. NM is most commonly dark brown, red-brown, or red-black and is dome-shaped, polypoid, or pedunculated. It is occasionally amelanotic (flesh-colored) and resembles flesh-colored dermal nevi or basal cell carcinoma. These amelanotic melanomas represent 1.8% to 8.1% of all melanomas. NM is the type of melanoma most frequently misdiagnosed because it resembles a blood blister, hemangioma, dermal nevus, seborrheic keratosis, or dermatofibroma (see Figure 22-32 ).

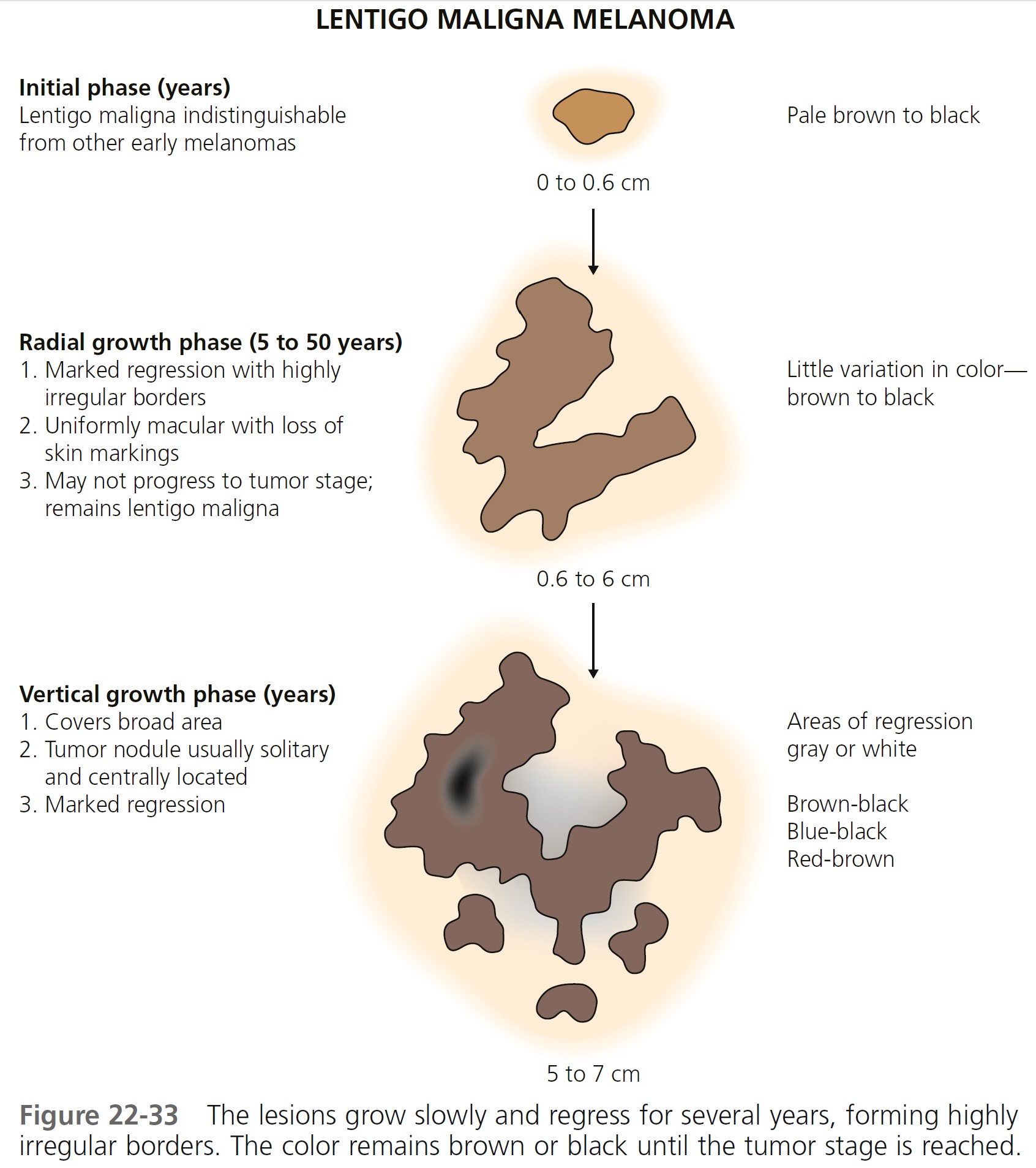

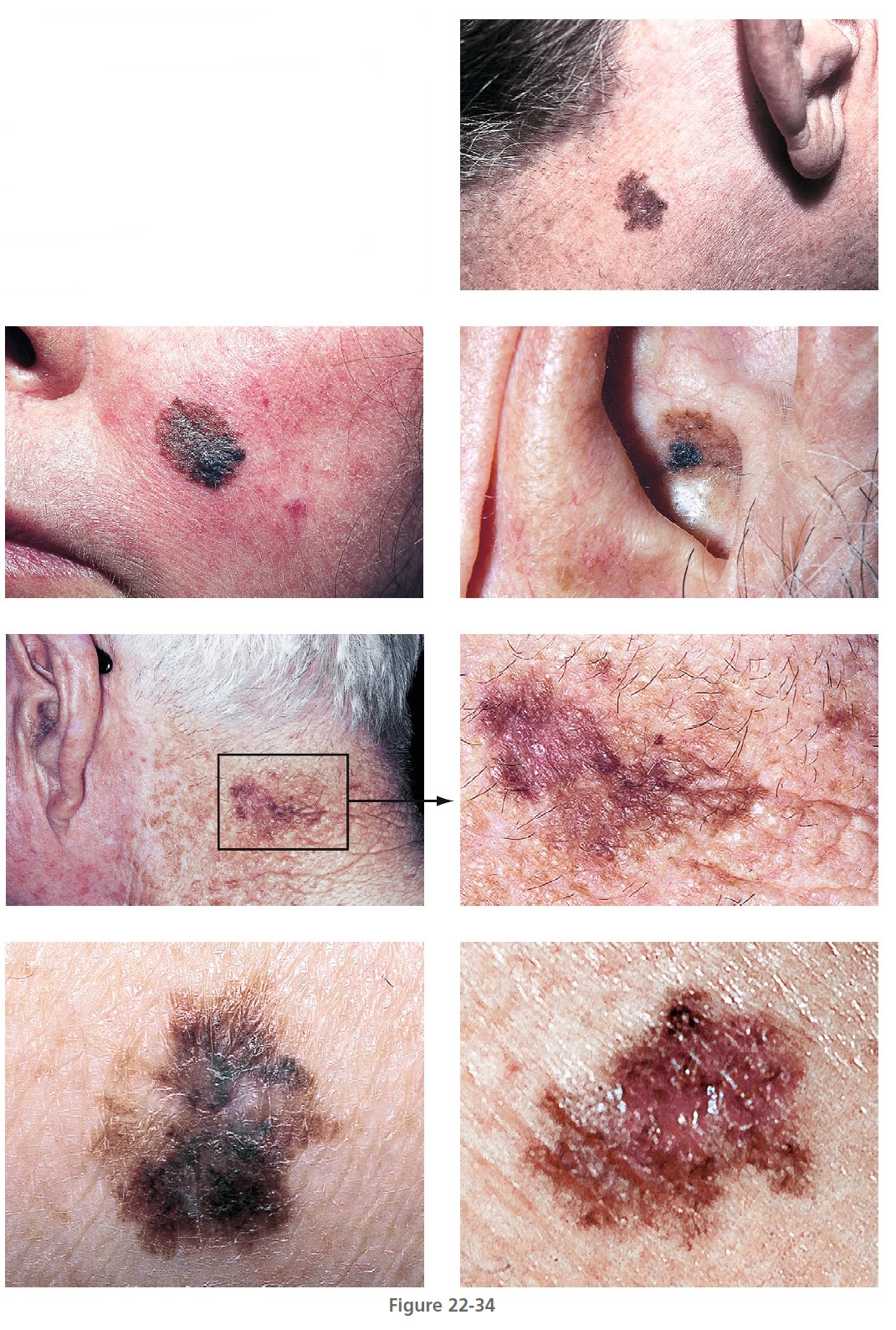

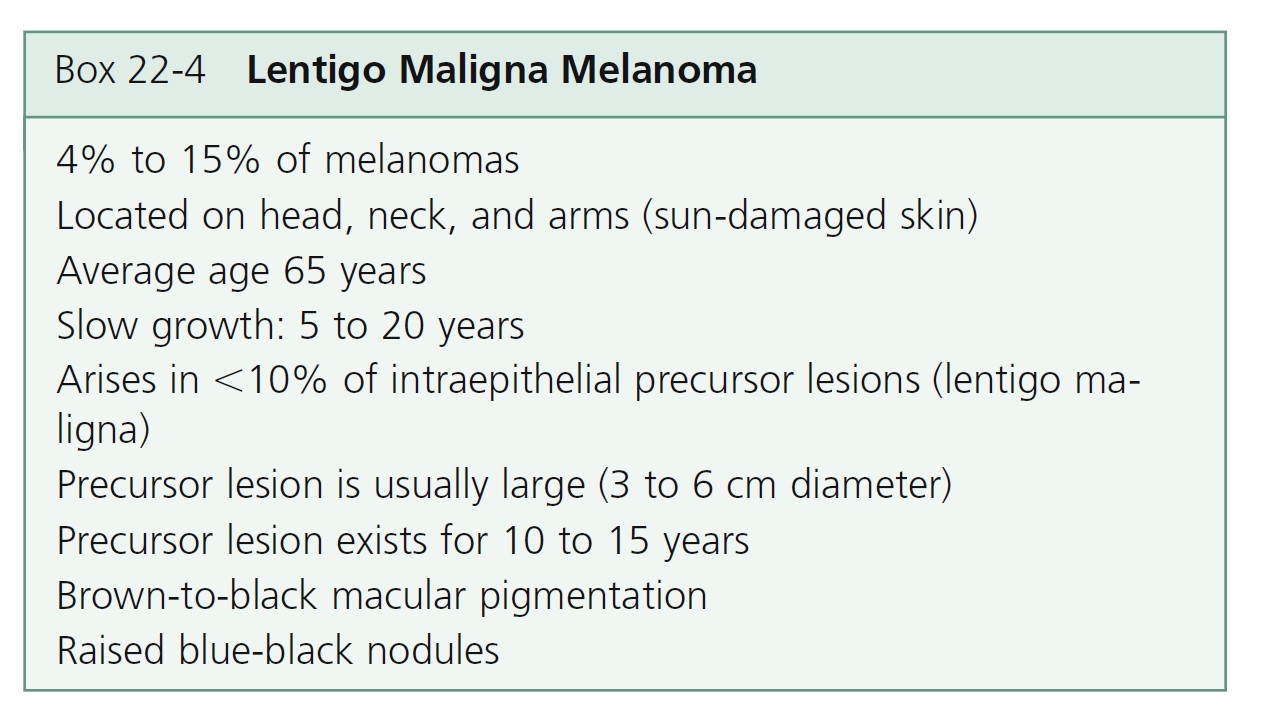

Lentigo maligna melanoma

Lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM) ( Figures 22-33 and 22-34 , Box 22-4 ) usually presents in the sixth or seventh decade. Most are located on the face, but 10% are on other exposed sites, such as the arms and legs. The radial growth phase is called lentigo maligna (LM) or Hutchinson’s freckle. The radial growth phase may last for years and never develop a vertical growth phase. The risk of progression of LM to LMM varies with age, but is lower than commonly believed. For a patient aged 45 years with LM, the estimated risk of developing LMM by age 75 is 3.3%. Estimated lifetime risk of transformation to melanoma is 4.7%. For a patient aged 65 years with LM, the risk of developing LMM is 1.2%, and the lifetime risk of transformation to melanoma is 2.2%. These risk estimates apply to patients in whom LM is discovered incidentally.

LMM may have a complex pattern. Years of migration and regression can produce lesions with a shape more varied and bizarre than that of SSM. The color is more uniform than SSM, but red and white may later occur. Tumors are generally in the center of the lesion, away from the border. LMM may ulcerate or undergo changes similar to other lesions when they enter the tumor stage. Nodules are usually single and generally appear when the lesion has assumed a size of 5 to 7 cm but may occur in much smaller lesions. LMM does not have a better prognosis than other forms of melanoma; as with other types of melanoma, the prognosis depends on tumor thickness.

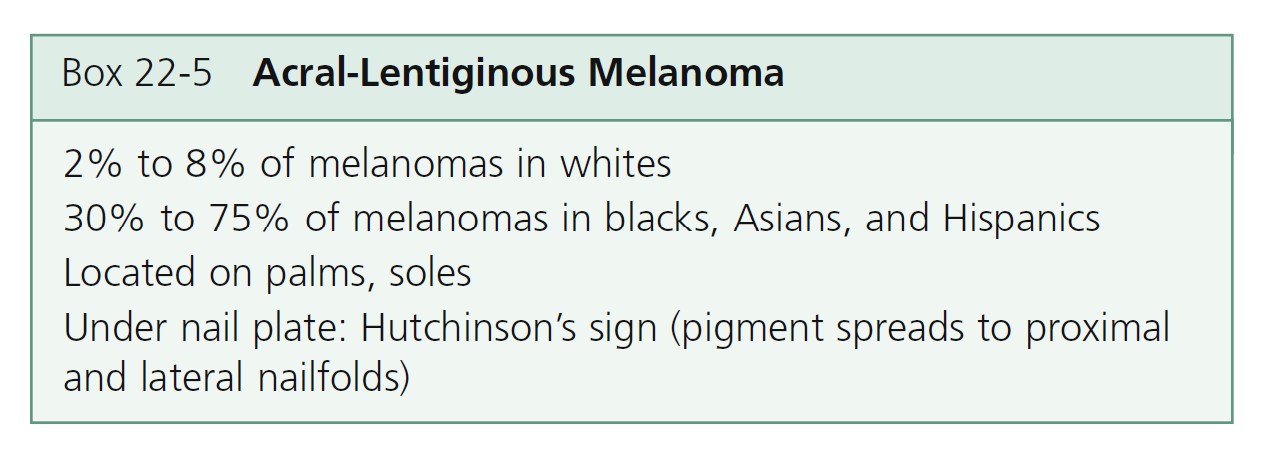

Acral-lentiginous melanoma

Acral-lentiginous melanoma (ALM) ( Figures 22-35 to 22-38 , Box 22-5 ) appears on the palms, soles, terminal phalanges, and mucous membranes. Similar in clinical presentation to LM and LMM, ALM has the same colors and tendency to remain flat. Like LM, plantar melanomas may remain latent for a number of years, making patients with these lesions good candidates for therapeutic cures if detected early. ALM is most frequent in blacks and Asians. The sole of the foot is the most prevalent site of malignant melanoma in non-whites. Small areas of elevation may be associated with deep invasion; the tumor is very aggressive and metastasizes early. The sudden appearance of a pigmented band originating at the proximal nailfold (Hutchinson’s sign) is suggestive of acral-lentiginous melanoma (see Figure 22-36 ). Acquired melanocytic lesions on the sole larger than 7 mm in maximum diameter should be examined histologically.

RARE TYPES. The following melanoma variants account for less than 2% of melanomas: melanoma arising from congenital nevus, mucosal (lentiginous) melanoma, ocular melanoma, malignant blue nevus, amelanotic melanoma (no pigment), and desmoplastic/neurotropic melanoma (markedly fibrotic stroma).

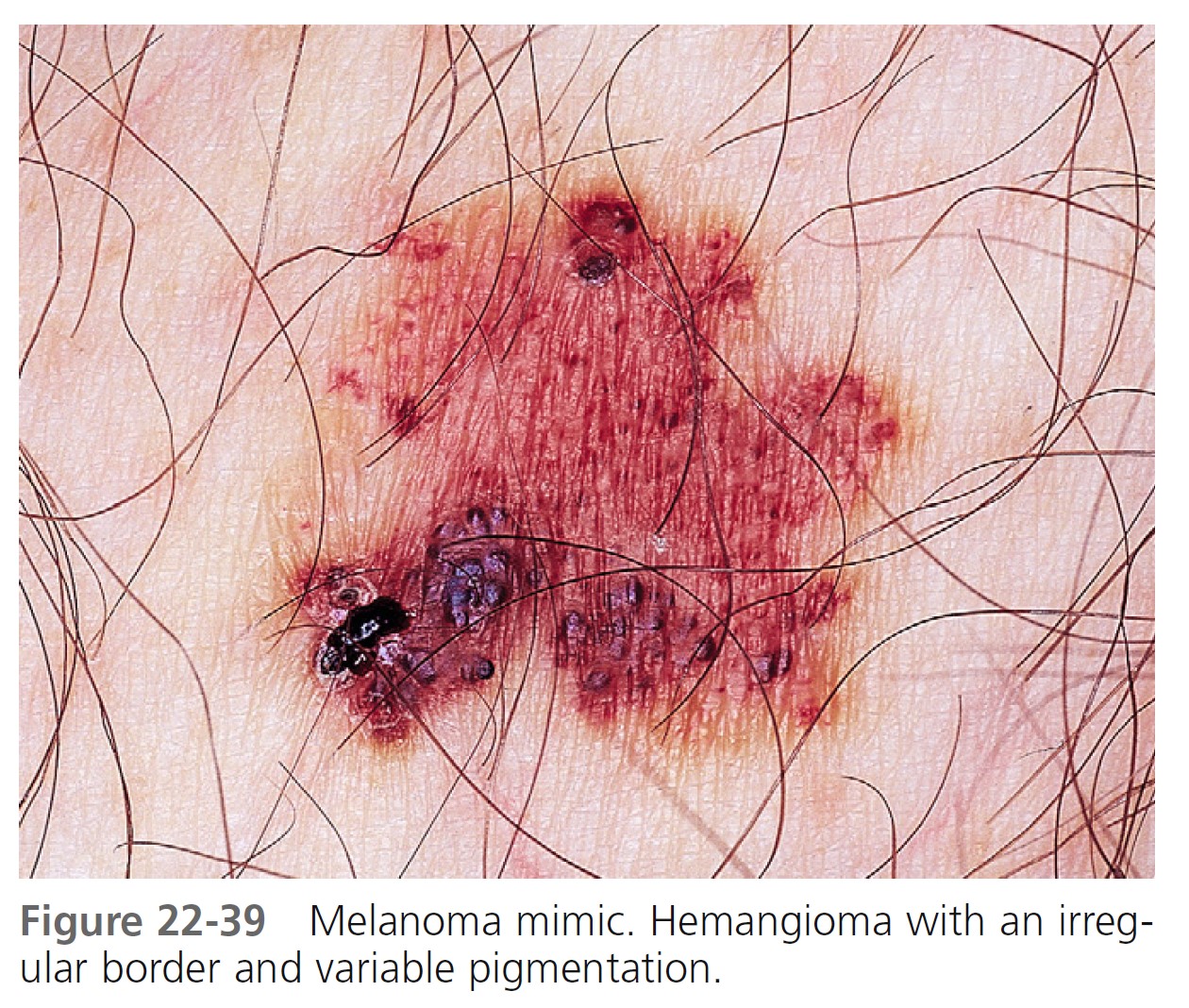

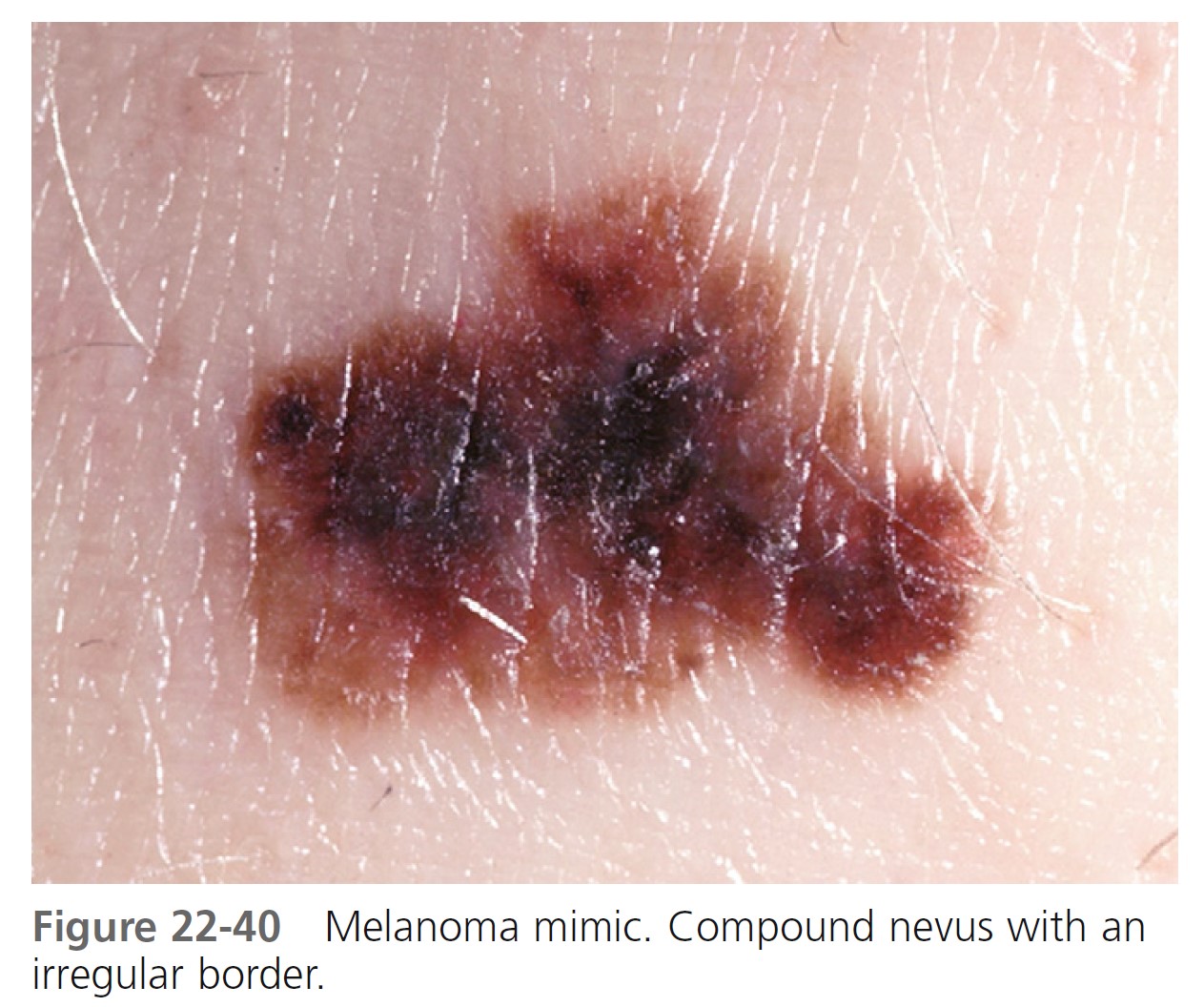

Benign lesions that resemble melanoma

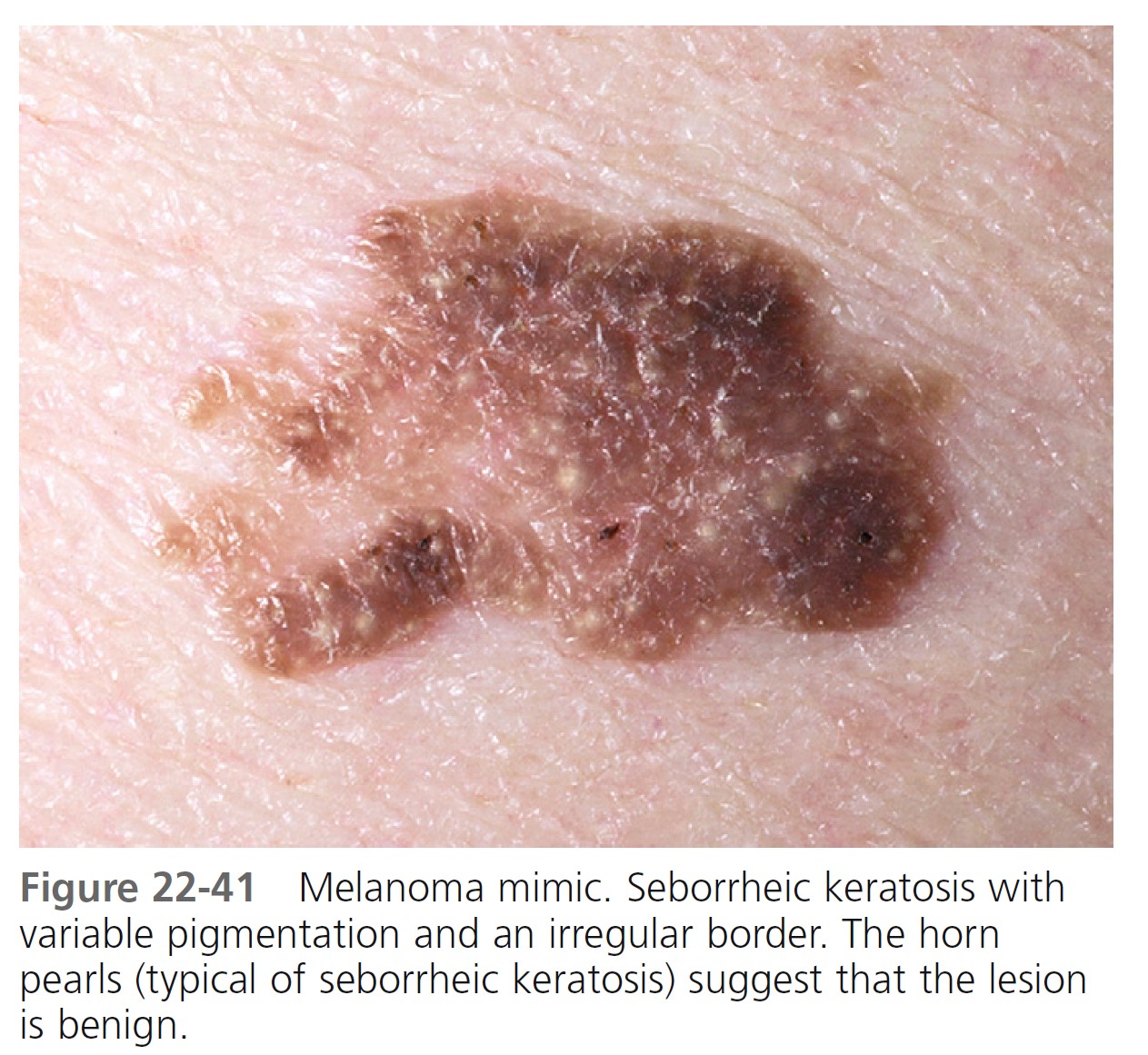

Typical nevi or other lesions, such as those of seborrheic keratosis, angiomas, and dermatofibromas, may have features that suggest melanoma. Biopsy specimens of these lesions should be obtained ( Figures 22-39 to 22-42 ).

LESION EXAMINATION

OBSERVATION PLUS MAGNIFICATION PLUS DERMOSCOPY. Several different lesions can be recognized by observation or magnification with a 10x ocular micrometer. The 10x ocular micrometer is a superior instrument for studying the surface characteristics of seborrheic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, dermatofibroma, compound nevi, dermal nevi, halo nevi, and hemangiomas. Many lesions can be scanned quickly. The dermoscope (see Figure 22-46 ) is an invaluable instrument for examination of flat to slightly raised pigmented lesions such as atypical nevi and lesions suspected of being melanoma. Examining numerous seborrheic keratoses with a dermoscope is inefficient. The horn pearls and keratin structure are clearly appreciated with 10x ocular magnification.

SCREENING FOR MELANOMA. Most pigmented lesions can be diagnosed on the basis of clinical criteria. Examination of the surface with 10x magnification is highly recommended for the initial evaluation of all skin growths. However, there are many small lesions in which the distinction between a benign and malignant process cannot be made by observation and magnification. Dermoscopy is useful for the diagnosis of these doubtful skin lesions.

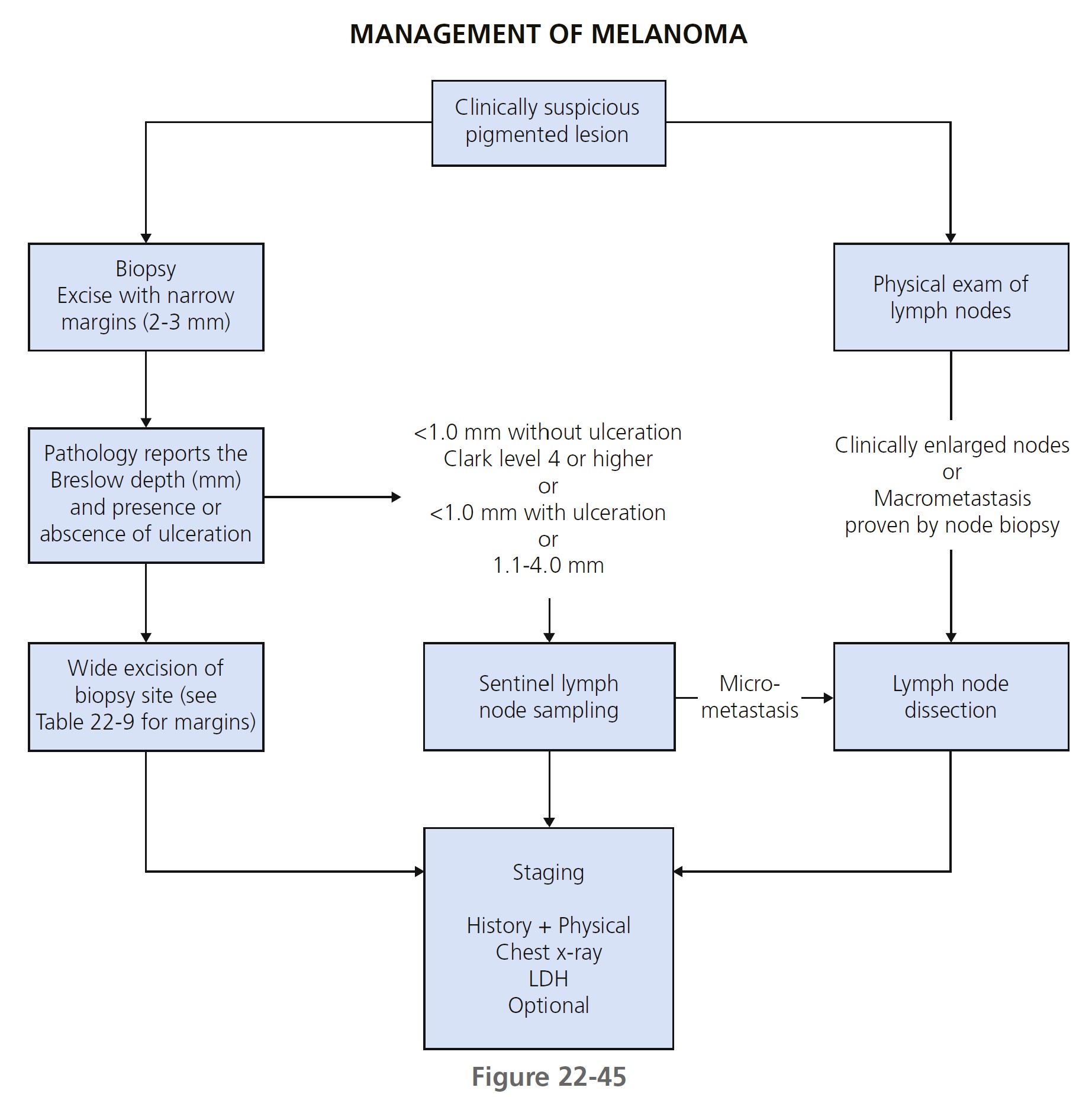

MANAGEMENT OF MELANOMA

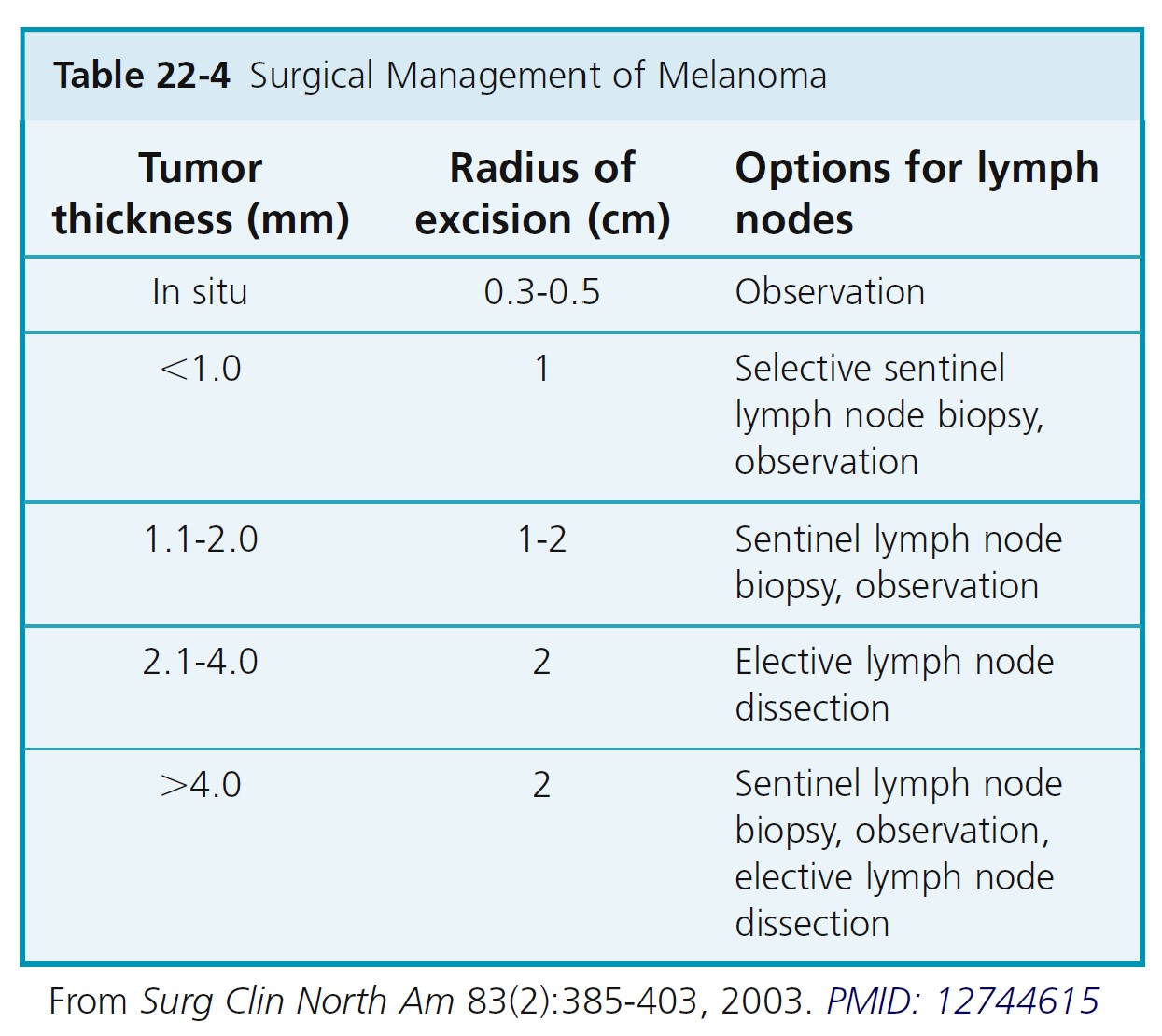

The classification and management of melanomas are summarized in Tables 22-4 to 22-8.

Biopsy

Whenever possible, excise the lesion for diagnostic purposes using narrow margins (2 to 3 mm of normal skin). Wider margins (>1 cm) may disrupt cutaneous lymphatic flow and affect the ability to identify the sentinel node(s). Incisional biopsy does not adversely affect survival. A punch biopsy technique is appropriate when the suspicion for melanoma is low, when the lesion is large, or when it is impractical to perform an excision. Punch through the thickest part of the lesion. Perform a repeat biopsy if the initial biopsy specimen is inadequate for accurate histologic diagnosis or staging. Shave biopsies are discouraged because partial removal of the primary melanoma may not provide accurate Breslow depth measurement.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS AND PROGRESSION

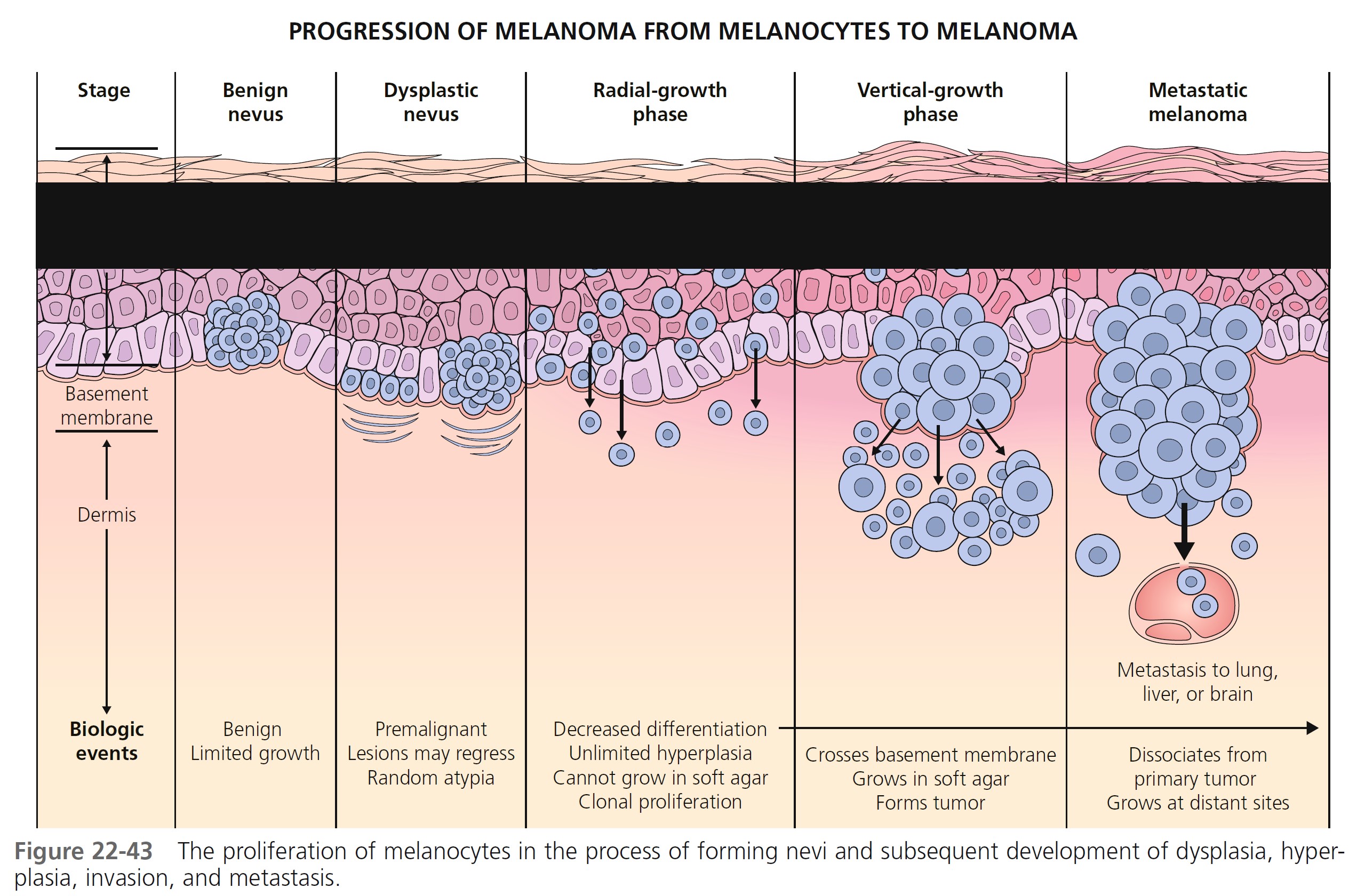

Melanocytes progress through a series of steps toward malignant transformation ( Figure 22-43 ). The first step is a proliferation of melanocytes to form nests along the basal layer to form a benign nevus.

The next step is the formation of a dysplastic nevus. Random cytologic atypia appears in the basement membrane area. Clinically, lesions increase in diameter, show variation in color and symmetry, and have irregular borders. Cells that degenerate to cancer (melanoma) loose the ability to remain localized. They enter the radial growth phase and proliferate intradermally. All cells have changed to atypical tumor cells. Cells penetrate into the papillary dermis singly or in small nests and the lesion becomes slightly raised. The vertical growth shows cells invading the papillary dermis and reticular dermis. Lentiginous melanoma initially have an in situ radial growth phase and in time may enter a vertical growth phase. Lateral intraepidermal extension of melanoma cells occurs in all subtypes except nodular melanoma.

RADIAL GROWTH PHASE TUMORS. Large and atypical melanocytes first proliferate in the epidermis above the epidermal basement membrane. They are arranged haphazardly at the dermal-epidermal junction, show upward (pagetoid) migration, and lack the biologic potential to metastasize. They then invade the papillary dermis (Clark level 2). Malignant cells confined above the epidermal basement membrane (in situ) or in the papillary dermis (microinvasive) are called radial growth phase melanomas. These are almost always less than 1 mm thick.

VERTICAL GROWTH PHASE TUMORS. Tumors that have invaded the reticular dermis have entered the vertical growth phase. They have metastatic potential. There are mitoses and nuclear pleomorphism. Cells fail to maturate as the tumor extends downward into the dermis. Clark level 3 and 4 tumors are usually in the vertical growth phase.

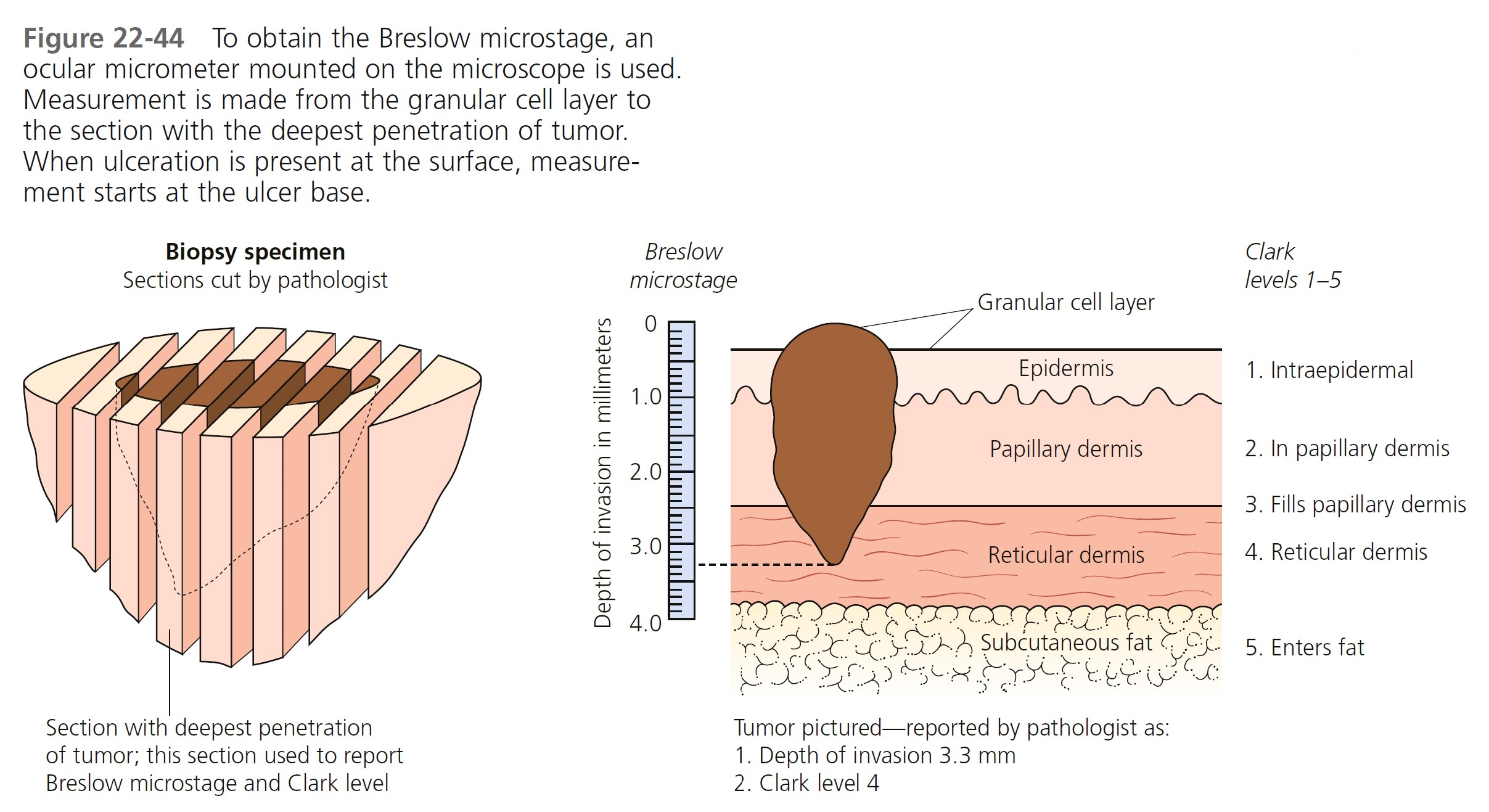

TUMOR THICKNESS (BRESLOW MICROSTAGE). Tumor thickness, as defined by the Breslow depth, is the most important histologic determinant of prognosis. The tumor is step-sectioned ( Figure 22-44 ). The section with the deepest level of penetration of tumor is used to measure thickness. An ocular micrometer is placed on the microscope. The pathologist measures the thickness of the tumor in millimeters from the top of the granular cell layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest part of the tumor. The report is given as Breslow level, followed by the depth reported in millimeters.

ULCERATION. The presence of ulceration microscopically, defined as the loss of epidermis overlying the melanoma, is the next most important histologic determinant of patient prognosis and should be used to upstage patients with melanoma when present.

TUMOR THICKNESS (CLARK LEVEL). Clark levels measure tumor invasion anatomically. The tumor depth is reported by anatomic site (e.g., epidermis, depth in dermis) and assigned a Clark level of invasion (see Figure 22-44 ). Clark levels appear to affect prognosis only in thinner (<1-mm depth) melanomas.

PATHOLOGY REPORT. The pathologist determines the tumor thickness in millimeters (Breslow level) and presence of ulceration.

Reporting of other histologic features is encouraged: Clark level, growth phase, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes, mitotic rate, regression, angiolymphatic invasion, microsatellitosis, neurotropism, and histologic subtype.

MITOTIC RATE. The mitotic rate per square millimeter in the dermal part of the tumor is reported. Although ulceration is considered the most important prognostic factor after Breslow thickness for localized cutaneous melanoma, many studies have shown that mitotic rate is a significant prognostic factor.

TUMOR-INFILTRATING LYMPHOCYTES. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are defined as brisk, nonbrisk, and absent. An infiltrative lymphocytic response may indicate favorable survival.

HISTOLOGIC REGRESSION. Areas of epidermis and dermis that have no recognizable tumor and are flanked by areas of melanoma indicate regression. Many studies have found regression to be associated with a worse prognosis and decreased survival. Regression is thought to be particularly important in thin melanomas. Extensive regression can be found in patients with thin (<1 mm) melanomas associated with metastases.

ANGIOLYMPHATIC INVASION AND ANGIOTROPISM. Vascular invasion in nodular melanomas is associated with tumor thickness, histologic diameter, ulceration, lymph node involvement, and distant metastases. Angiotropism is a prognostic factor that predicts risk of metastasis.

Special stains. The pathologist may use immunohistochemical staining for lineage (S-100, homatropine methylbromide 45) or proliferation markers (proliferating cell nuclear antigen, Ki67) in difficult cases.

Surgical therapy

EXCISION AFTER BIOPSY (RESECTION MARGINS)

Complete surgical removal of the entire neoplasm must be accomplished with histologic verification of removal. Recommended surgical margins based on depth of the tumor (Breslow measurement) and diameter of the melanoma are listed in Table 22-4.

Compromises are necessary for lesions on the digits, head and neck, and face. Excising to deep fascia is not thought to be necessary for melanoma tumors confined to the upper levels of the skin. It does not improve local recurrence or survival rates. Wider cutaneous margins may be appropriate for large in situ tumors.

METASTATIC STAGING AND PROGNOSIS

The presence or absence of micrometastasis in the sentinel lymph node (SLN) is the most important prognostic factor for recurrence and the most powerful predictor of survival.

SENTINEL LYMPH NODE BIOPSY. The SLN is defined as the first node in the lymphatic basin that drains the lesion and is at the greatest risk for the development of metastasis. Although no survival benefit has been proven for the procedure, the staging information is useful in identifying patients who may benefit from further surgery or adjuvant therapy.

Indication. SLN biopsy is appropriate for melanomas deeper than 1.0 mm and for tumors 1 mm or less when histologic ulceration is present and/or classified as Clark level 4 or higher. The SLN biopsy is inappropriate for nonulcerated Clark level 2 or 3 melanomas 0.75 mm or less in depth and is uncertain in tumors 0.76 to 1.0 mm deep unless they are ulcerated or are Clark level 4 or higher.

Procedure. Preoperative radiographic mapping (lymphoscintigraphy) and vital blue dye injection around the primary melanoma or biopsy scar (at the time of wide local excision or reexcision) are performed to identify and remove the initial draining regional node(s). Some centers use technetium 99m-labeled radioisotope and a hand-held gamma probe. The sentinel node is examined for micrometastasis with histology and immunohistochemistry. A therapeutic lymph node dissection is performed if micrometastasis is present. Preceding diagnostic excisions of malignant melanoma with a maximum margin of 10 mm do not alter the lymphatic flow or interfere with accurately obtaining the SLN of the primary tumor.

There are several reasons to perform sentinel lymph node biopsy. It improves the accuracy of staging and provides valuable prognostic information to guide treatment decisions. It facilitates early therapeutic lymph node dissection for those patients with nodal metastases. SLN biopsy identifies patients who are candidates for adjuvant therapy with interferon alfa-2b and identifies homogeneous patient populations for entry into clinical trials of adjuvant therapy agents.

ELECTIVE LYMPH NODE DISSECTION. Patients with clinically enlarged lymph nodes and no evidence of distant disease should undergo a complete regional lymph node dissection. The value of elective lymph node dissection for other patients has not been defined. Randomized surgical trials fail to support a role for elective lymph node dissection in patients with clinically negative lymph nodes.

Initial diagnostic workup

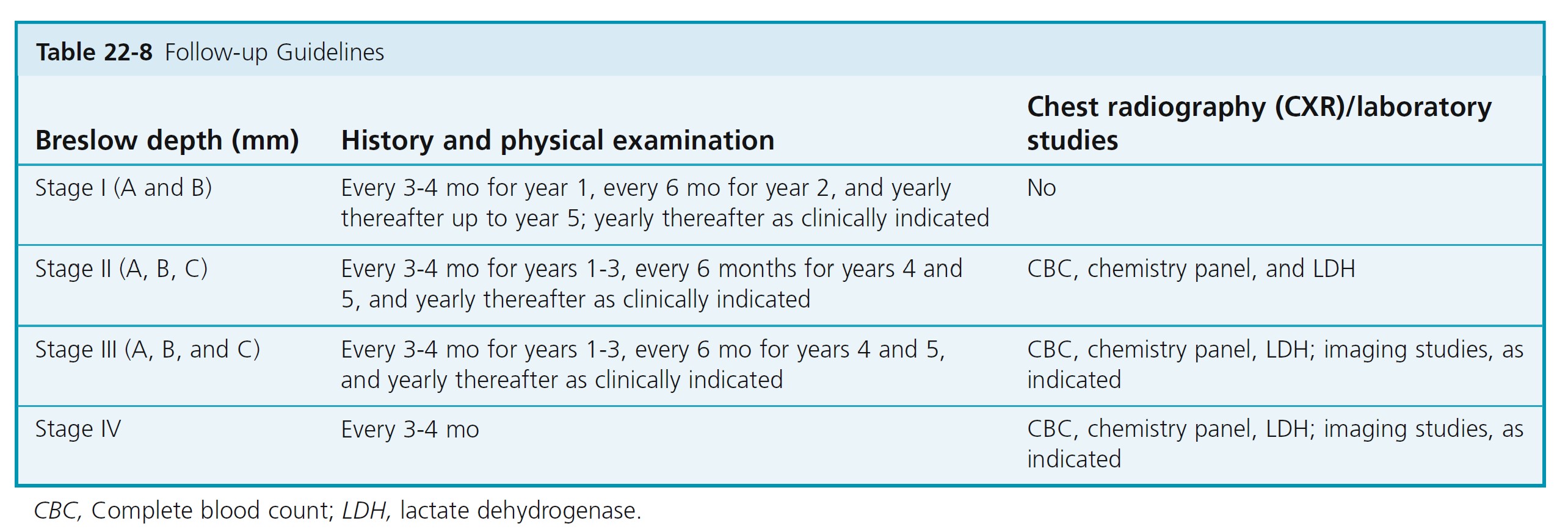

Routine imaging studies including chest radiography and blood work have limited, if any, value in the initial workup of asymptomatic patients with primary cutaneous melanoma 4 mm or less in thickness. On the other hand, negative results may alleviate patient anxiety. Indications for initial imaging studies and blood work are most appropriately directed based on findings from a thorough medical history and thorough physical examination ( Table 22-8 ).

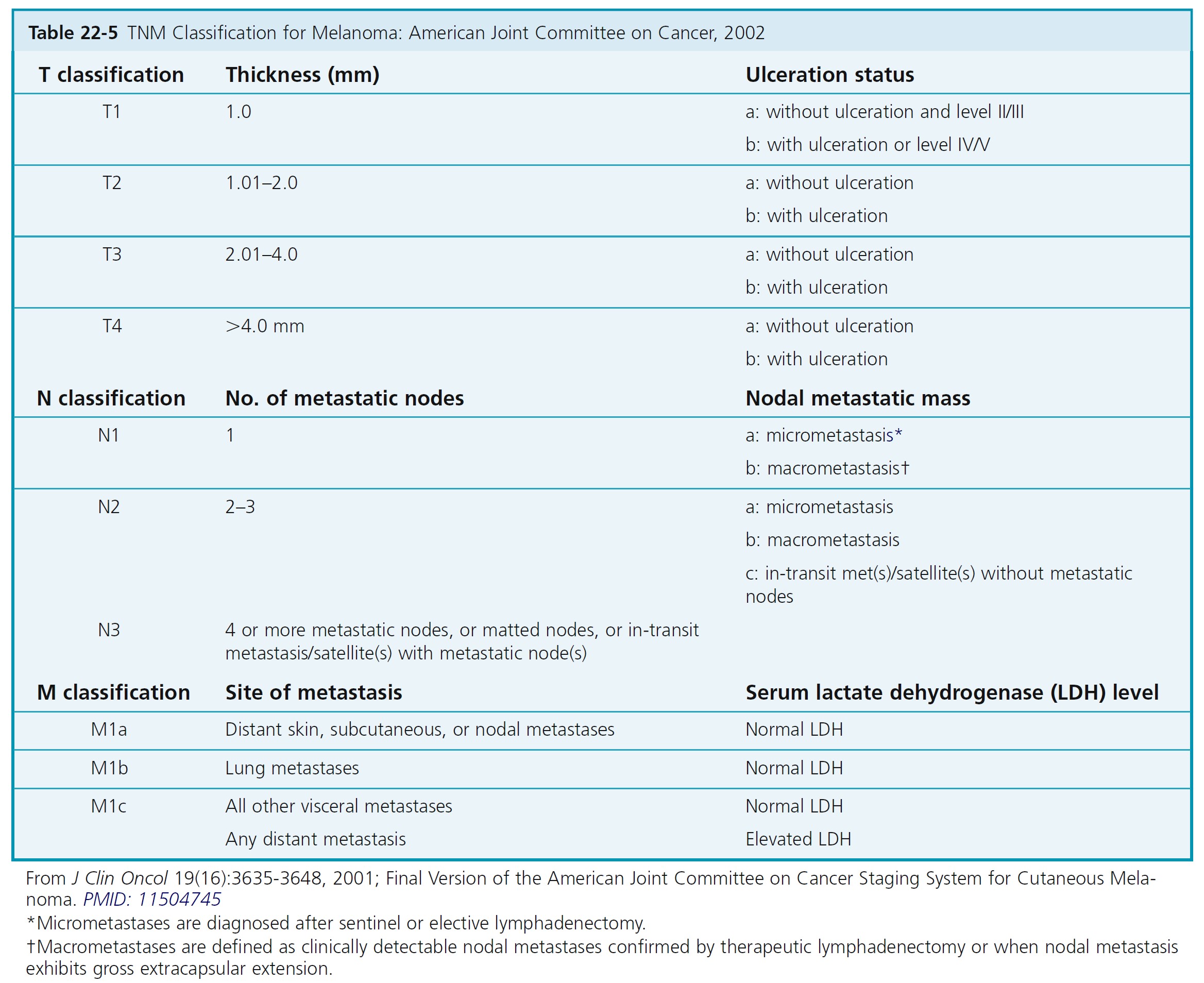

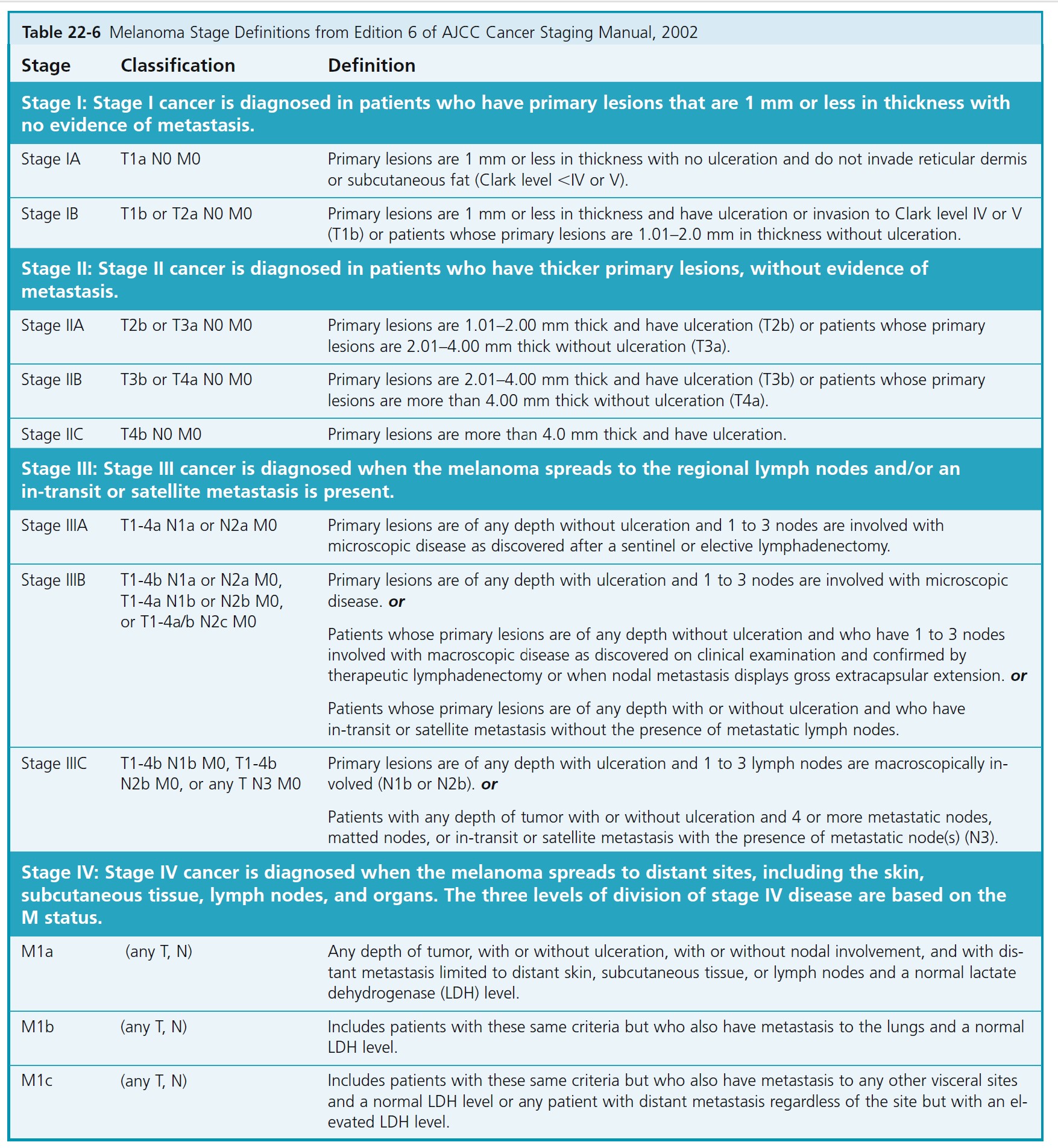

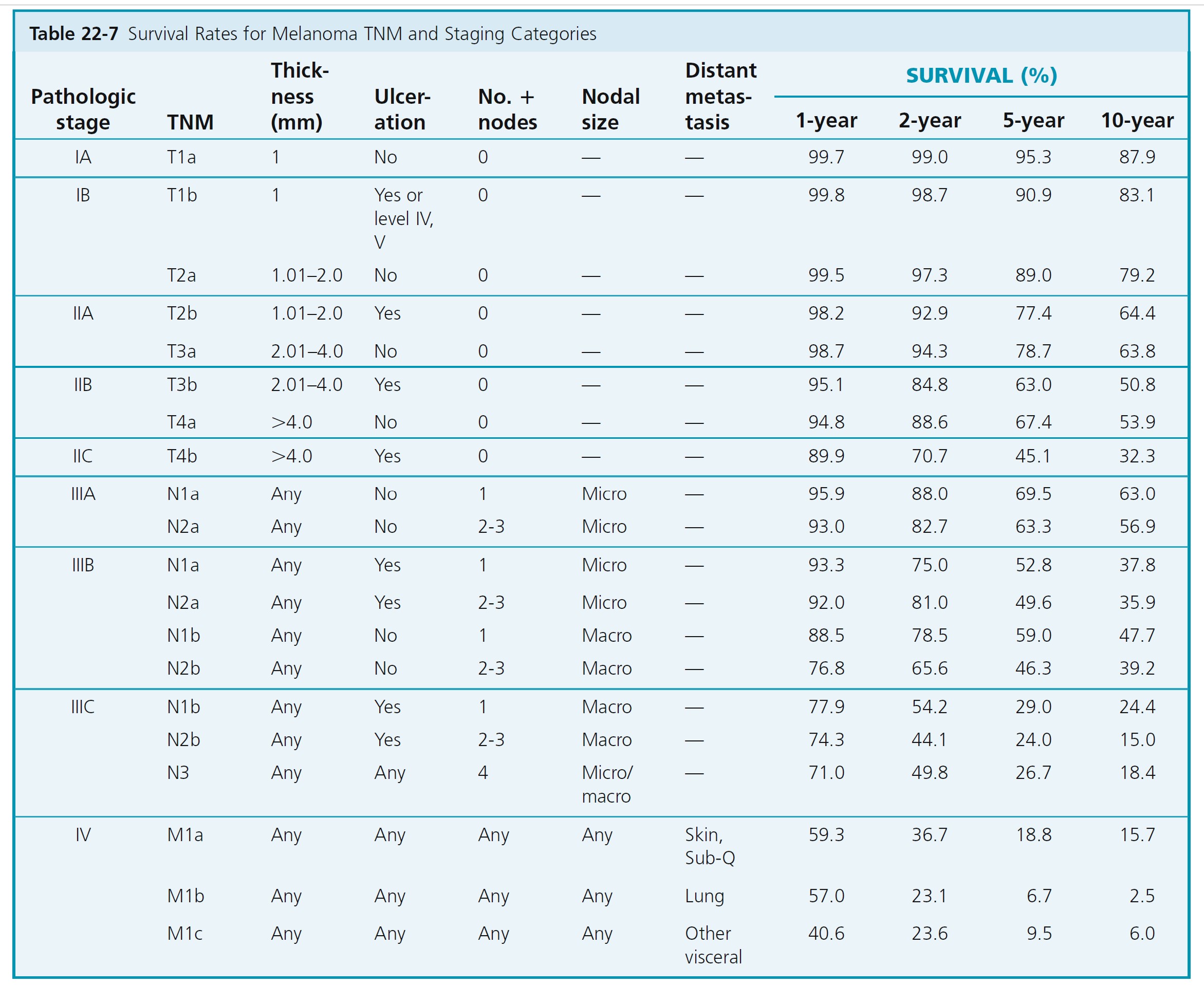

STAGING AND PROGNOSIS

The melanoma staging criteria were updated with the publication of the 6th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual in 2002. Tables 22-5 and 22-6 describe the stages of melanoma and the median survival associated with each stage.

The AJCC staging criteria for melanoma are divided into four stages. Localized melanoma is classified under stage I and stage II. Stage III melanoma includes regional metastases, and stage IV distant metastases. Each stage uses the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classifications when determining stage of disease.

The histologic evaluation of melanoma provides critical staging information. The depth of invasion (Breslow level expressed in millimeters) is the most important histologic prognostic parameter in evaluating the primary tumor. The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Melanoma Staging Committee studied 17,600 melanomas. Results of this evidence-based study were incorporated into the 2002 AJCC melanoma TNM staging classification. The 2002 AJCC staging system incorporates Breslow depth, Clark level, and ulceration. Tumor thickness and ulceration were the most powerful predictors of survival. The level of invasion (Clark level) had significance only in thin (≤1.0 mm) melanomas.

Staging for localized melanoma: Stages I and II

MELANOMA THICKNESS

The primary criteria for the T classification are tumor thickness (measured in millimeters) and the presence or absence of ulceration (determined histopathologically). Ten-year survival rates for each of the T categories in clinically staged patients are shown in Table 22-7 . Stage groupings are used to determine follow-up examination intervals ( Table 22-8 ). The sole difference in the definitions of clinical versus pathologic stage grouping is whether the regional lymph nodes are staged by clinical/radiologic examination or by pathologic examination (after partial or complete lymphadenectomy).

ULCERATION

Melanoma ulceration is defined as the absence of an intact epidermis overlying a major portion of the primary melanoma based on microscopic examination of the histologic sections. Melanoma ulceration heralds such a high risk for metastases that its presence upstages the prognosis of all such patients compared with patients who have melanomas of equivalent thickness without ulceration. Survival rates for patients with an ulcerated melanoma are proportionately lower than those for patients with a nonulcerated melanoma of equivalent T category but are similar to those of patients with a nonulcerated melanoma of the next highest T category.

PATHOLOGIC STAGING OF LYMPH NODES

The number of lymph nodes is the most important feature, followed by the tumor burden within the lymph node. If 1 node is involved, the classification is N1; if 2 to 3 nodes are involved, the classification is N2; and if 4 or more metastatic nodes, matted nodes, or in-transit metastases or satellites with metastatic node(s) are involved, the classification is N3.

Lymph nodes with disease identified by immunostains only and not seen with hematoxylin-eosin staining are considered N0. A special designation of N0 (immunohistochemically positive) is used.

Follow-up examinations

Follow patients to detect asymptomatic metastases and additional primary melanomas. Demonstrate self-examination of skin and lymph nodes. Routine physician examinations are performed at least annually. History and physical examination directs the need for laboratory tests and imaging studies.

An overview of the management of melanoma is shown in Figure 22-45.

Follow-up intervals

Patients with thicker tumors have elevated risk of recurrence in the early years after diagnosis and need to be followed more frequently (see Table 22-8 ).

Recurrence may develop after 10 years or more of a patient being disease free. Late recurrence may be local, and survival subsequent to treatment of these metastases is often protracted. Therefore patients with cutaneous melanoma should be observed for life.

Medical treatment

Adjuvant high-dose interferon-alfa produces increases in relapse-free survival rates and overall survival rates in selected patients (stages IIB, IIC, IIIA, IIIB, IIIC). Interferon alfa-2b therapy is used for patients with regional nodal and/or in-transit metastasis and for node-negative patients with primary melanomas deeper than 4 mm. The use of interferon alfa-2b therapy is uncertain in patients with ulcerated intermediate primary tumors (2.01 to 4.0 mm in depth) and inappropriate for node-negative patients with nonulcerated tumors less than 4.0 mm deep. Vaccines and biologic response modifiers show promise in prolonging survival.

TREATMENT OF LENTIGO MALIGNA

Lentigo maligna is found predominantly in areas of actinic damage where cosmetically unsatisfactory scars may result from conventional surgery. Cryosurgery is an efficient alternative to conventional surgery provided that patients are selected properly and extension of cryonecrosis is monitored. Several case reports and studies suggest that lentigo maligna responds to 5% imiquimod cream (Aldara).

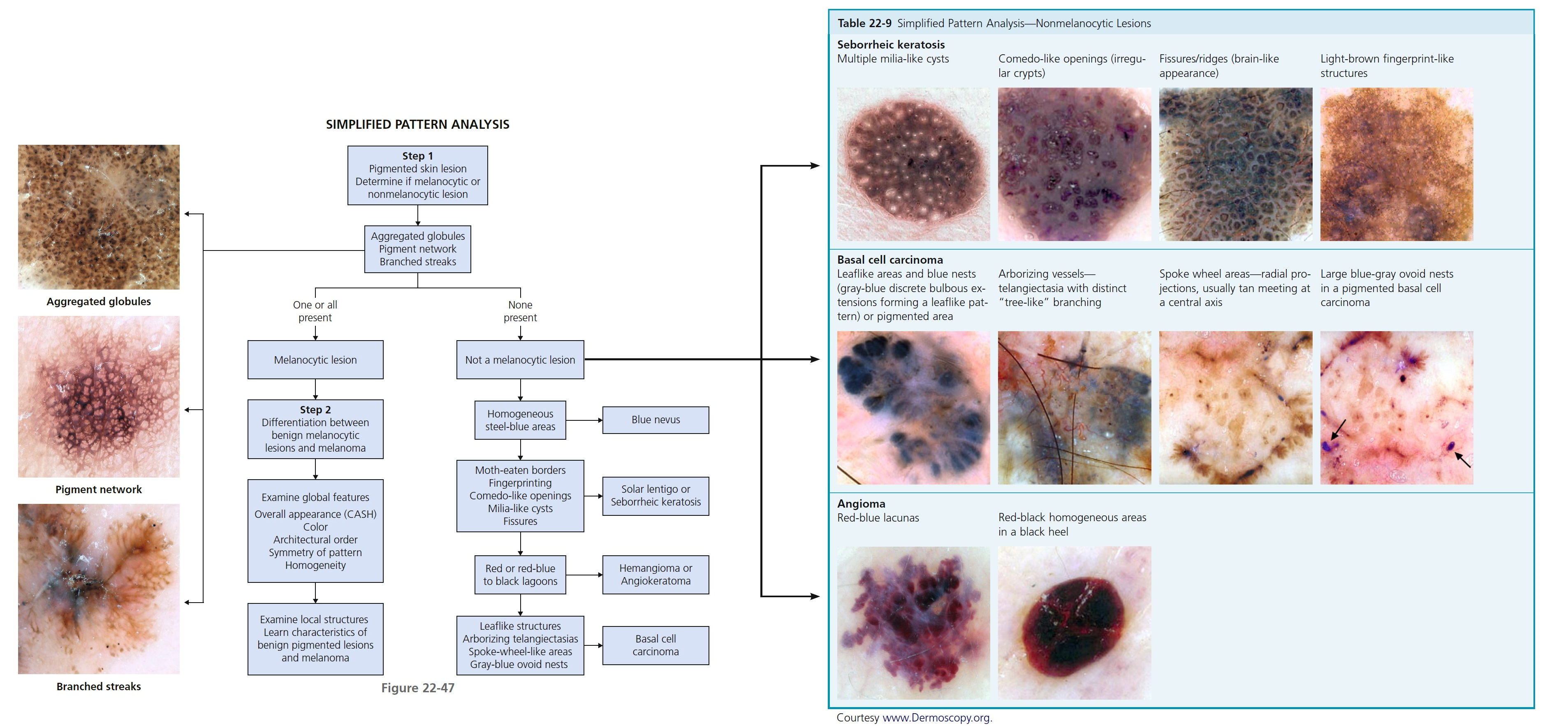

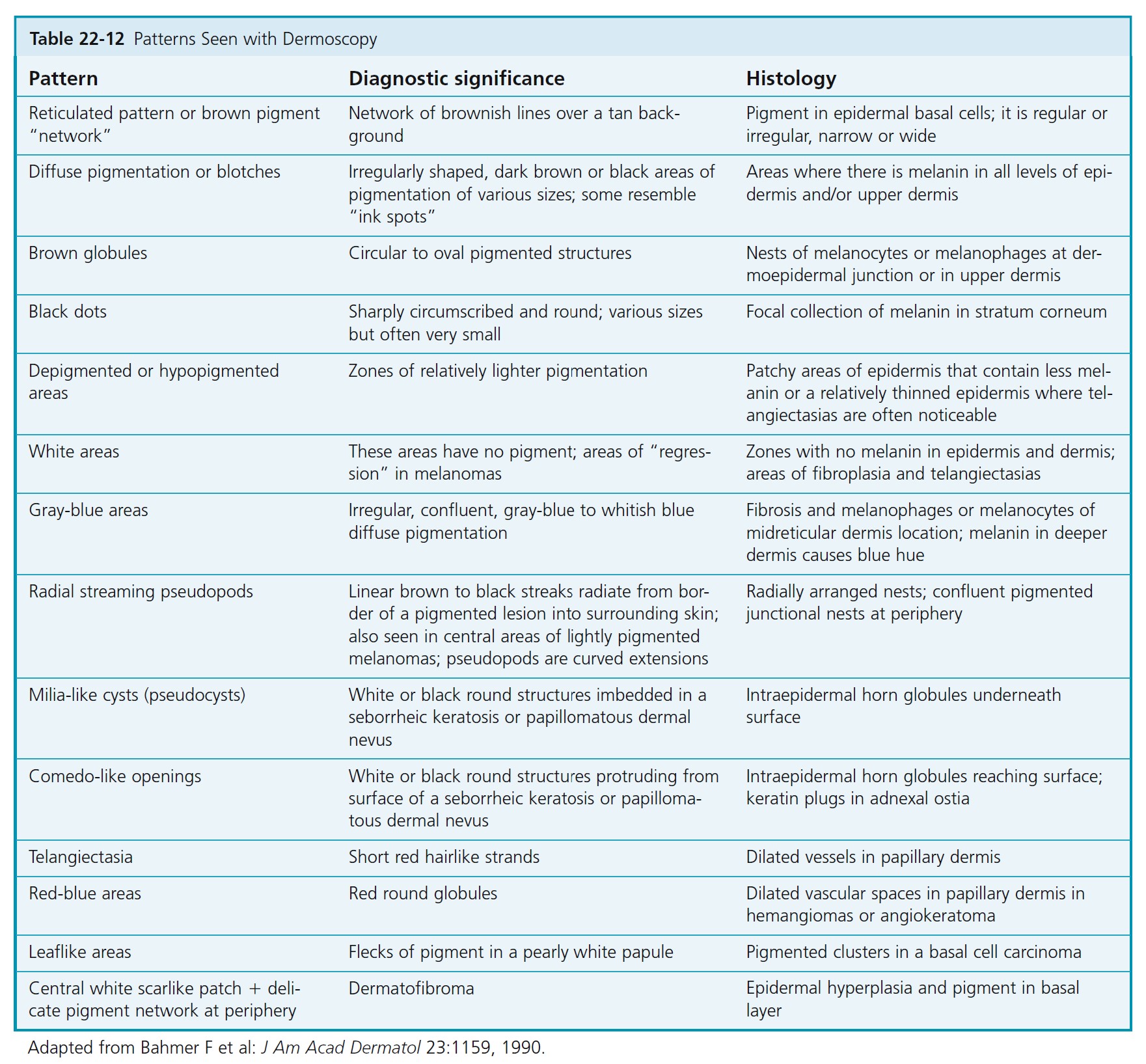

DERMOSCOPY

Dermoscopy (epiluminescent microscopy, magnified oil immersion diascopy) is a technique used to see a variety of patterns and structures in lesions that are not discernible to the naked eye ( www.dermoscopy.org ). Lotion or mineral oil may be applied to the surface of the lesion to make the epidermis more transparent. Examination with a 10x ocular micrometer, a microscope ocular eyepiece (held upside down), or a dermoscope ( Figure 22-46 ) (available from surgical supply houses) reveals several features that are helpful in differentiating between benign and malignant pigmented lesions. The DermLite and DermoGenius are highly accurate oil-free pocket epiluminescent microscopes. A clear and deep view into pigmented lesions can be made in seconds with these instruments. Many lesions can be examined in a short time. Dermoscopy provides additional criteria for the diagnosis of melanoma.

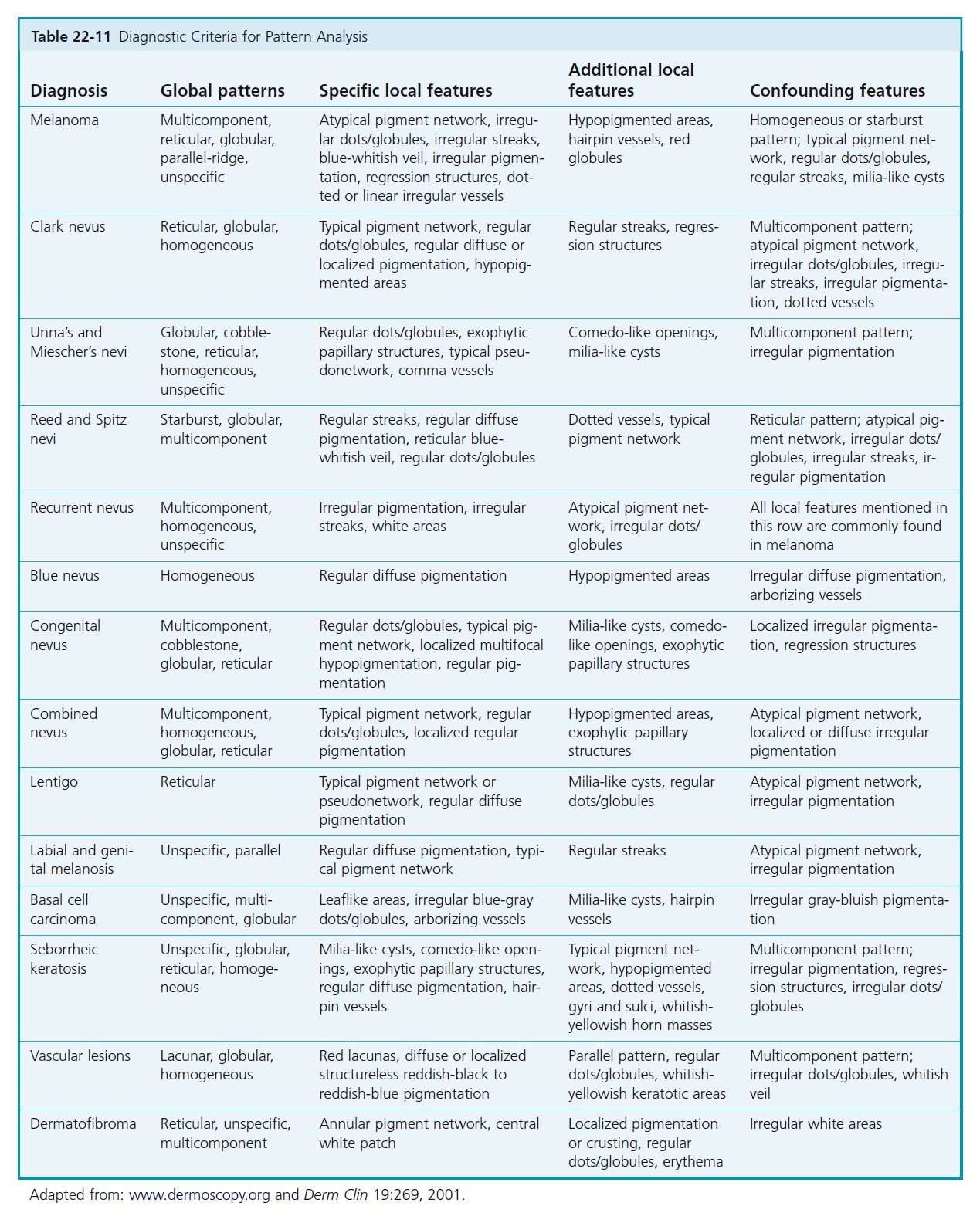

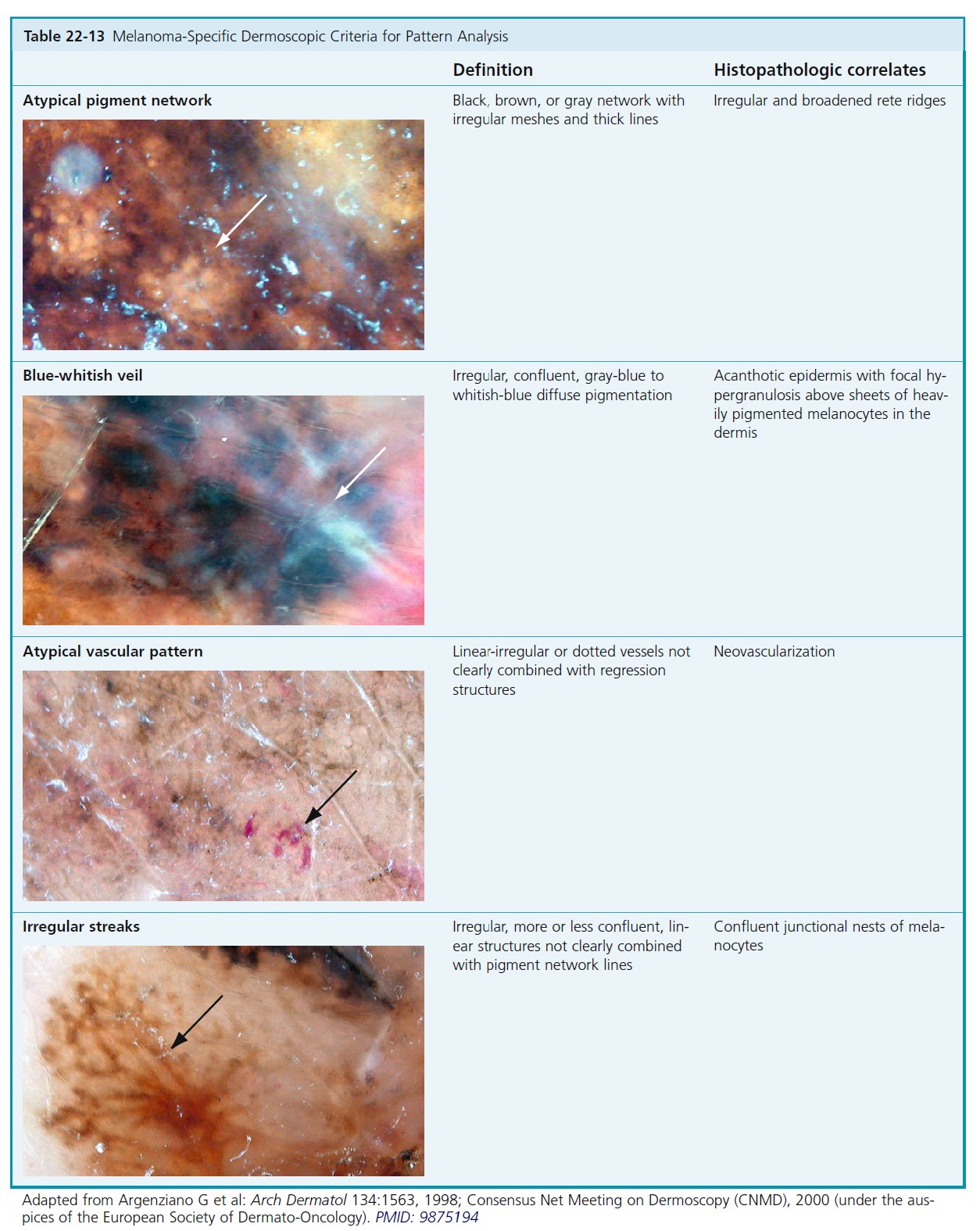

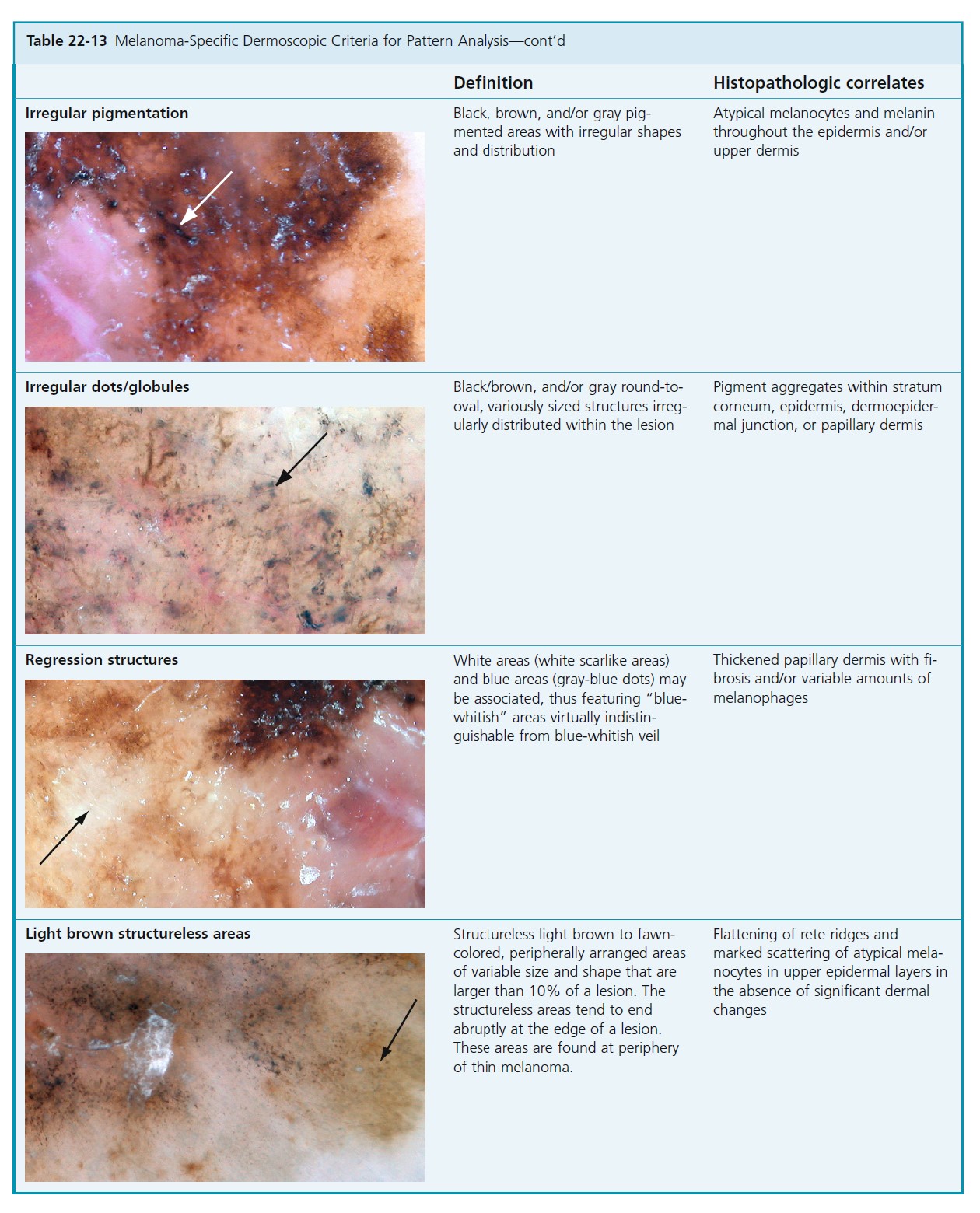

DERMOSCOPIC CHARACTERISTICS OF BENIGN AND MALIGNANT MELANOCYTIC LESIONS. A standardized terminology for dermoscopy patterns was established in 1989. A number of diagnostic methods using these criteria have been devised. Pattern analysis is based on the assessment of numerous individual criteria. A simplified Pattern Analysis method is accurate and easy to learn and is felt to be more accurate than other simplified methods.

SIMPLIFIED PATTERN ANALYSIS

There are two steps in the process of pattern analysis ( Figure 22-47 ). The first step is to decide whether the lesion is melanocytic or nonmelanocytic. Determine if aggregated globules, a pigment network, or branched streaks are present. If present the lesion is melanocytic (e.g., nevus, melanoma). If not look for structures characteristic of nonmelanocytic lesions. Learn characteristics of global features of pigmented lesions ( Figure 22-48 ) and local structures of benign pigmented lesions and melanoma to make a diagnosis.

See Figures 22-47 and 22-48 along with Tables 22-9 to 22-15 for a thorough path to dermoscopy analysis.

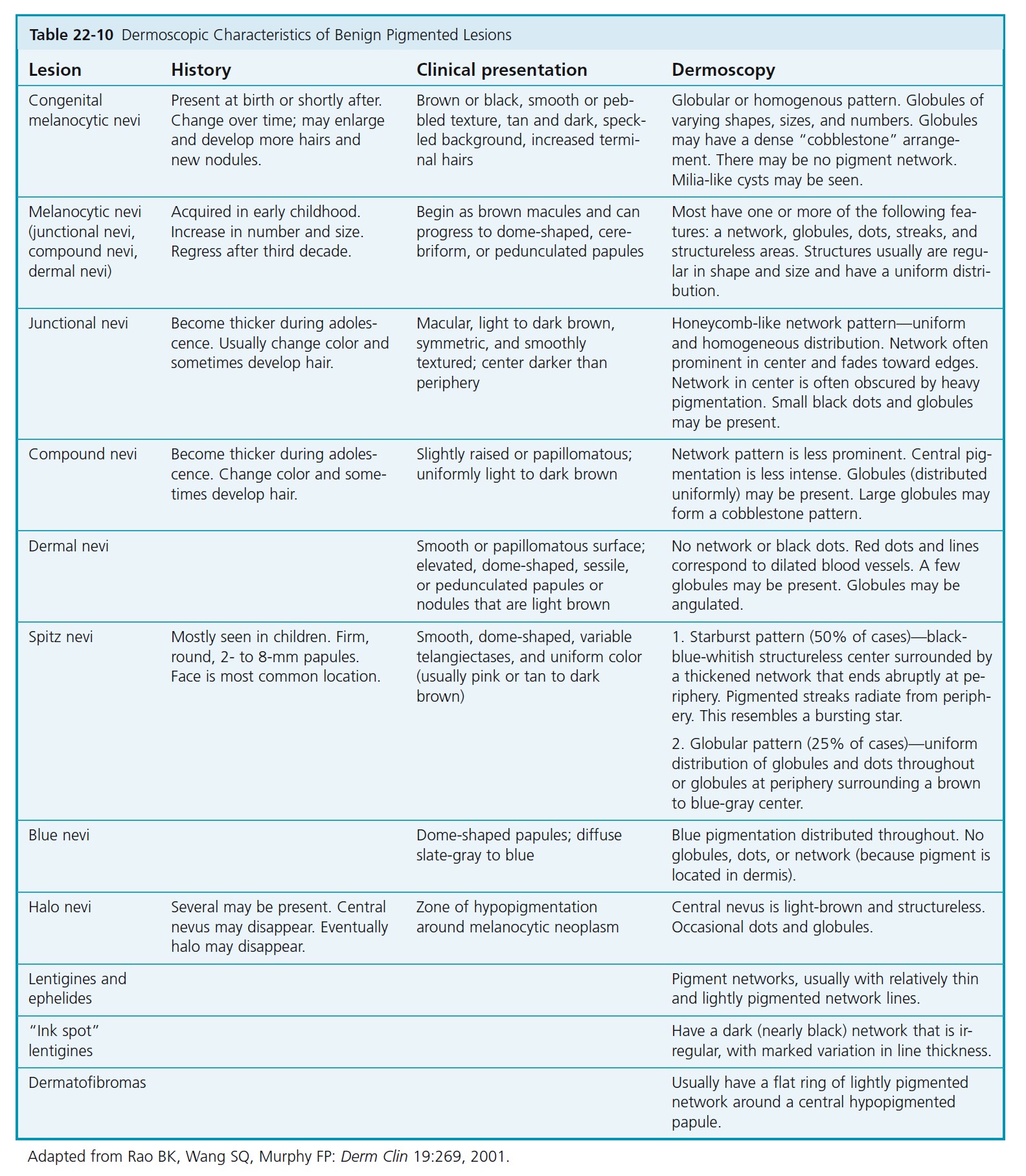

DERMATOSCOPIC CHARACTERISTICS OF BENIGN PIGMENTED LESIONS. The dermatoscopic characteristics of benign melanocytic nevi are described in Table 22-10 , and an example is shown in Figure 22-48.

THE PIGMENT NETWORK

The presence of a pigment network usually implies that the lesion is melanocytic. The pattern may be subtle or present only in a small area. The network of common lesions such as lentigo and junctional nevi fades and thins at the periphery. The typical honeycomb-like pattern of the pigment network on the trunk and proximal extremities results from pigmentation along the rete ridges. The pseudonetwork patterns on the face, palms, and soles result from junctional pigment outlining hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and eccrine ducts. Pigment on the palms and soles outlines linear skin markings along or across the skin furrows, resulting in a parallel, lattice, or fibrillar pattern. Growing melanomas distort the normal skin anatomy and cause variation in pigmentation patterns and structures. Networks in melanomas are variable. Thin melanomas and melanomas in situ may have only very subtle pigmentation changes. Subtle thickening and darkening of pigment network lines may be seen near the periphery in early lesions. As Breslow thickness increases, the pigment network tends to become more variable in thickness and color density. The lines become thick and dark. They also become darker near the periphery. These result from wide and shallow pigmented rete ridges. Pseudopods and radial streaming occur at the edge of a region of thickened, darkened network at the periphery.

Many lesions will lack classic dermoscopy features of melanoma. This ill-defined group of possible early melanomas will include many atypical nevi. Clinical judgment using all available information must be used to make the decision to excise or observe. Total number of lesions, history of melanoma, family history, body site, and surgical morbidity such as scarring are factors to consider before making the final management decision.

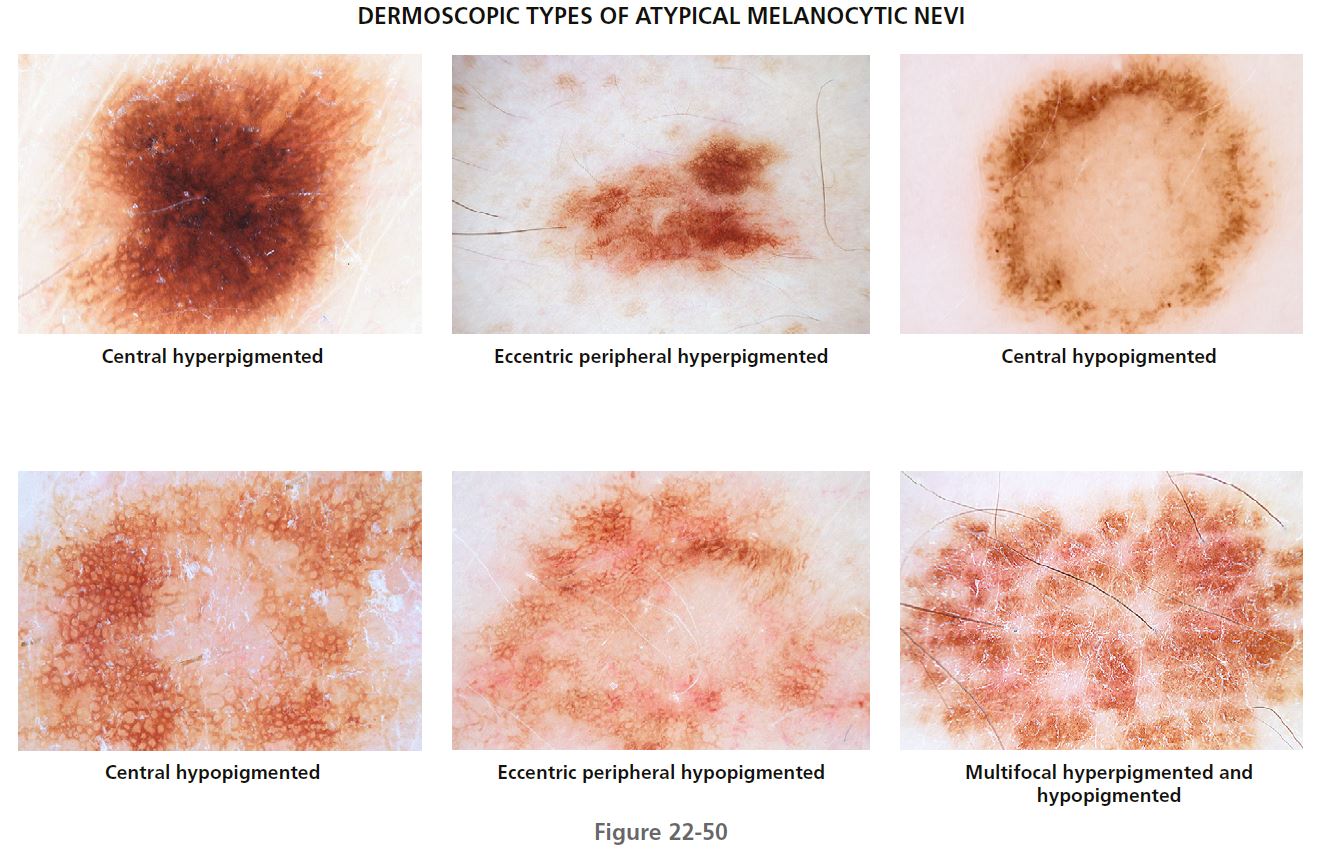

DERMOSCOPIC CLASSIFICATION OF ATYPICAL NEVI

STRUCTURAL FEATURES PLUS DISTRIBUTION OF PIGMENTATION. The following dermatoscopic classification allows characterization of the different dermatoscopic types of atypical nevi. Knowledge of these dermatoscopic types should reduce unnecessary surgery for benign melanocytic lesions ( Figures 22-49 and 22-50 ).

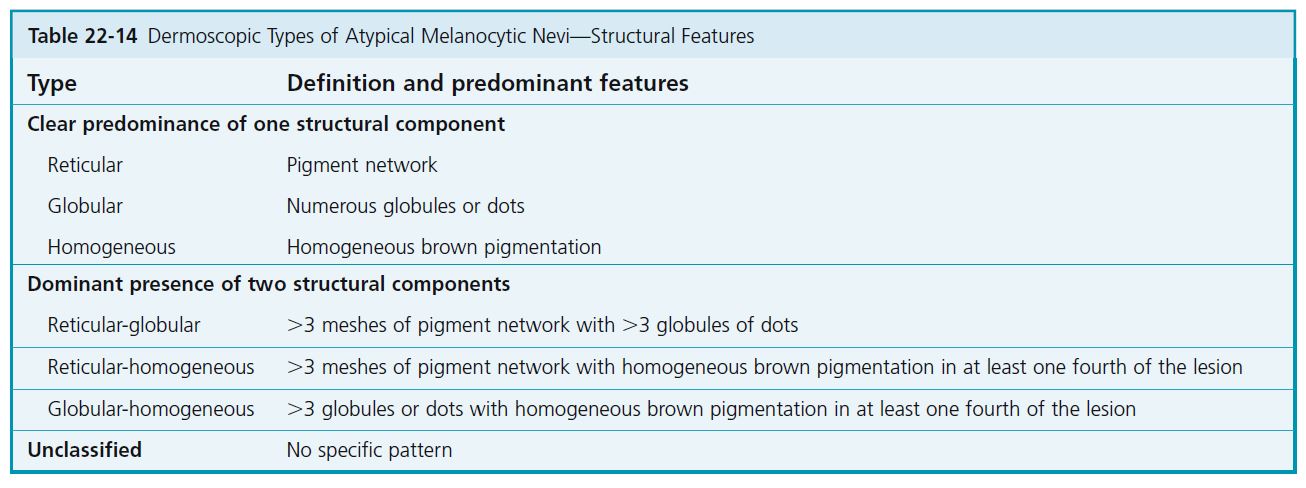

Atypical nevi are classified according to structural features, that is, reticular, globular, or homogeneous patterns, or combinations of these types. The nevi are also characterized by distribution of pigmentation (see Tables 22-13 and 22-15 ).

CLASSIFICATION BY MAIN STRUCTURAL COMPONENTS

Nevi are first classified according to structural features: reticular pigment network, pigmented globules, and homogeneous pigmentation (see Table 22-14 ). When a clear predominance of one of these structural components is seen, the nevus is classified as reticular, globular, or homogeneous.

CLASSIFICATION BY COMBINATIONS OF STRUCTURAL COMPONENTS

In the case of the dominant presence of two structural components, the nevus is classified as reticular-globular, reticular-homogeneous, or globular-homogeneous (see Table 22-14 ). No single nevus shows all three structural components. The most common are the reticular type, followed by the reticular-homogeneous and globular-homogeneous types.

CLASSIFICATION BY DISTRIBUTION OF PIGMENTATION

The distribution of the pigmentation is then classified as central hyperpigmented or hypopigmented, eccentric peripheral hyperpigmented or hypopigmented, and multifocal hyperpigmented or hypopigmented (see Table 22-15 ). In cases where hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation are present, classifi cation is based on the predominant distribution of color.

INTERPRETATION AND MANAGEMENT

Most individuals have one predominant type of nevus. A lesion that does not belong to the predominant type of nevus in a given patient should be considered an atypical lesion and therefore deserving of special attention.

Atypical nevi with the reticular pattern and uneven pigmentation are especially prone to overdiagnosis as melanoma. The most common heterogeneous distribution of pigmentation is multifocal hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, followed by central hypopigmentation and central hyperpigmentation. Eccentric peripheral hyperpigmentation is often found in malignant melanoma. Atypical nevi with eccentric peripheral hyperpigmentation should be regarded as the most relevant simulators of melanoma within the morphologic spectrum of atypical nevi. Therefore this type of nevus should be excised or monitored using digital dermoscopy at 3-month intervals. When the eccentric peripheral hyperpigmentation increases, excision of the lesion is necessary.

LIMITATIONS OF DERMOSCOPY

Dermoscopy may enhance the clinician’s ability to diagnose melanoma. Knowledge and experience are required. Even experienced users may obtain a false sense of security in 20% or more cases of melanoma that lack classic dermoscopy features of melanoma. The dermoscopy feature most common in thin melanomas (Breslow thickness of <0.75 mm) is an irregular pigment network. Atypical nevi often have hyperpigmentation and bridging of the rete ridges, which give them a similar appearance by dermoscopy. Dermoscopy criteria for melanoma variants such as amelanotic melanomas, desmoplastic melanomas, lentigo maligna melanoma, or nevoid melanomas are lacking. A patient’s report of change in a lesion is an important risk factor for melanoma. Approximately 10% of melanomas have no characteristic dermoscopy findings. The decision to perform a biopsy of a lesion of moderate to high clinical suspicion for melanoma before dermoscopy observation should not be changed by the lack of dermoscopy criteria for melanoma.