HYPERSENSITIVITY SYNDROMES

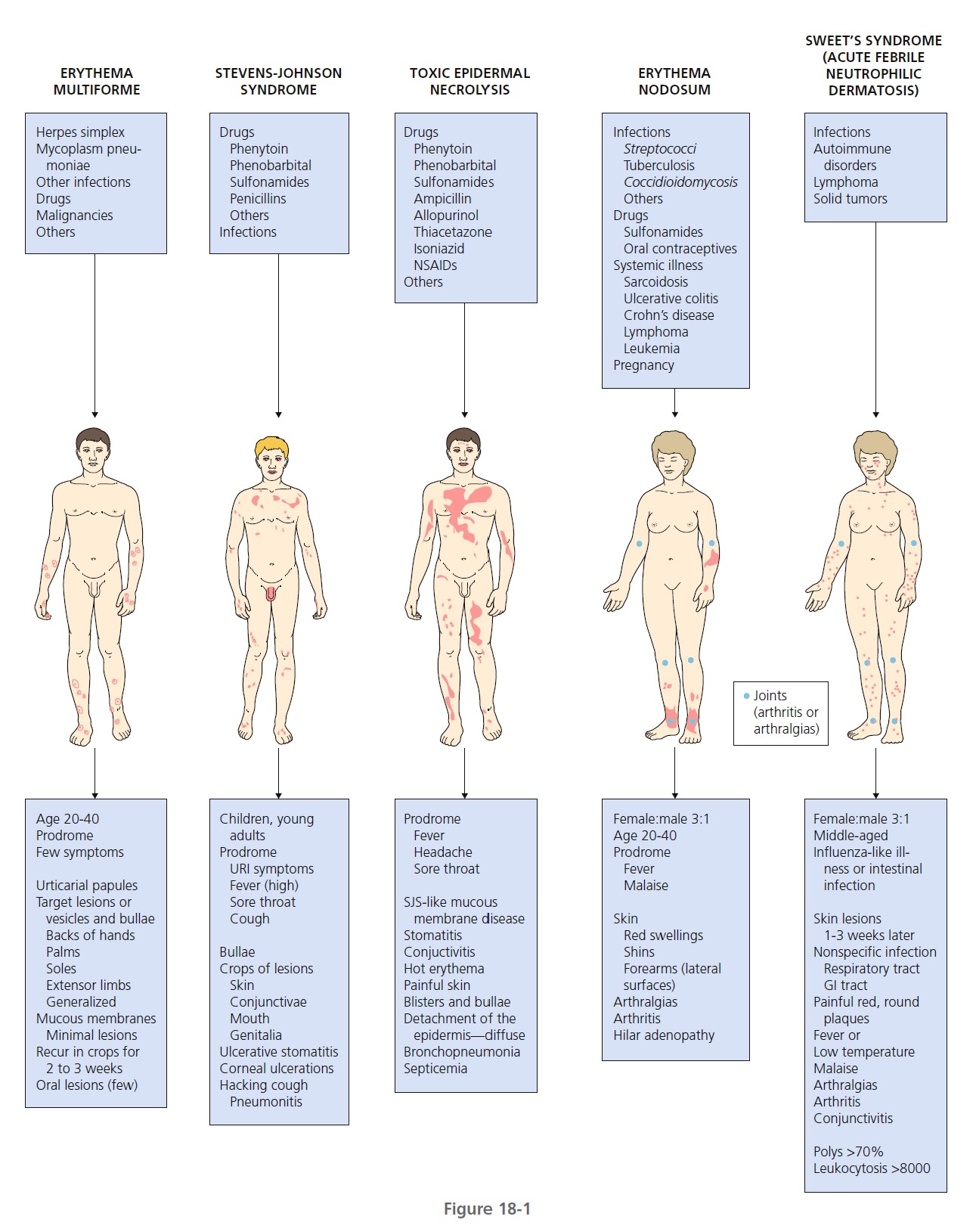

Hypersensitivity syndromes are displayed in Figure 18-1 .

ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME

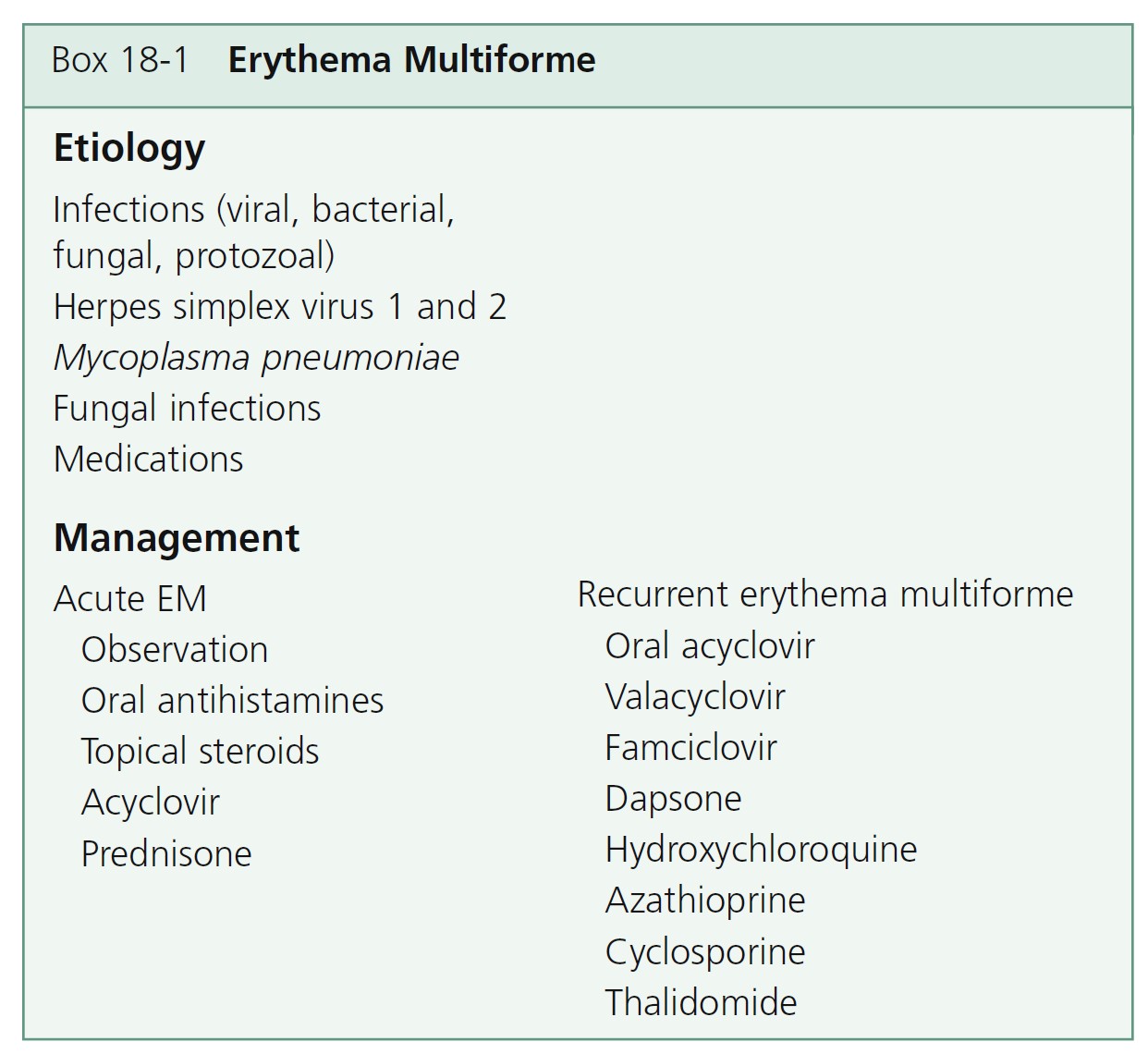

Erythema multiforme (EM) is a relatively common, acute, often recurrent inflammatory disease. Many factors have been implicated in the etiology of EM, including numerous infectious agents, drugs, physical agents, x-ray therapy, pregnancy, and internal malignancies ( Box 18-1 ). In approximately 50% of cases no cause can be found. EM is commonly associated with a preceding acute upper respiratory tract infection, herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, or Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection such as primary atypical pneumonia.

CLASSIFICATION. A new classification, based on the pattern and distribution of cutaneous lesions, separates erythema multiforme major from Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (see the section on Stevens-Johnson syndrome). Erythema multiforme differs from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis by occurrence in younger males, frequent recurrences, less fever, milder mucosal lesions, and lack of association with collagen vascular diseases, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or cancer. Recent or recurrent herpes is the principal risk factor for EM. Drugs have higher etiologic fractions for SJS and TEN.

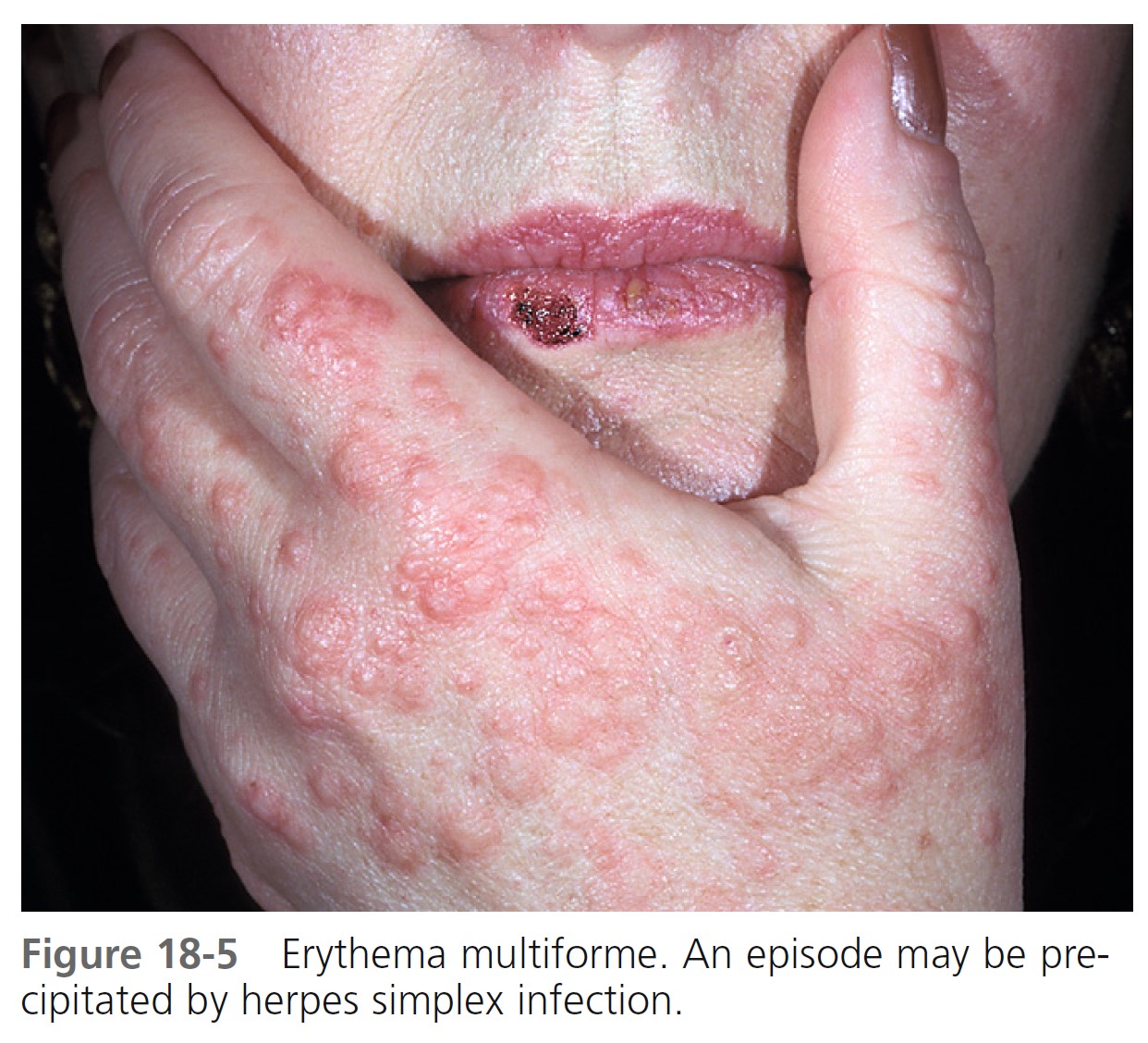

HERPES ASSOCIATED WITH RECURRENT EM. Herpes associated EM develops in only a few of the many individuals who experience recurrent herpes simplex virus infection. EM develops in some adults and children after each episode of herpes simplex. Skin biopsy specimens of EM lesions from patients with recurrent disease show HSV specific DNA in most cases.

PATHOGENESIS

Studies suggest that immune complex formation and subsequent deposition in the cutaneous microvasculature may play a role in the pathogenesis of EM. Circulating complexes and deposition of C3, immunoglobulin M (IgM), and fibrin around the upper dermal blood vessels have been found in the majority of patients with EM. Histologically, a mononuclear cell infiltrate is present about these same upper dermal blood vessels; in the other immune complex–mediated cutaneous vasculitis (leukocytoclastic vasculitis), polymorphonuclear leukocytes are present. EM shows lichenoid inflammatory infiltrate and epidermal necrosis that mainly affects the basal layer. Necrotic keratinocytes range from individual cells to confluent epidermal necrosis. The epidermodermal junction shows changes ranging from vacuolar alteration up to subepidermal blisters. The dermal infiltrate is mostly perivascular. SJS has a predominantly necrotic pattern in which major epidermal necrosis and minimal inflammatory infiltration are found. Acrosyringeal concentration of keratinocyte necrosis in EM occurs in drug-related cases and is more likely to be accompanied by a dermal inflammatory infiltrate containing eosinophils. Drug concentration in sweat may explain this pattern with subsequent toxic and immunologic mechanisms leading to the fully evolved lesion. Erythema multiforme has a high-density cell infiltrate rich in T lymphocytes. In contrast, toxic epidermal necrolysis is characterized by a cell-poor infiltrate in which macrophages and dendrocytes predominate.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

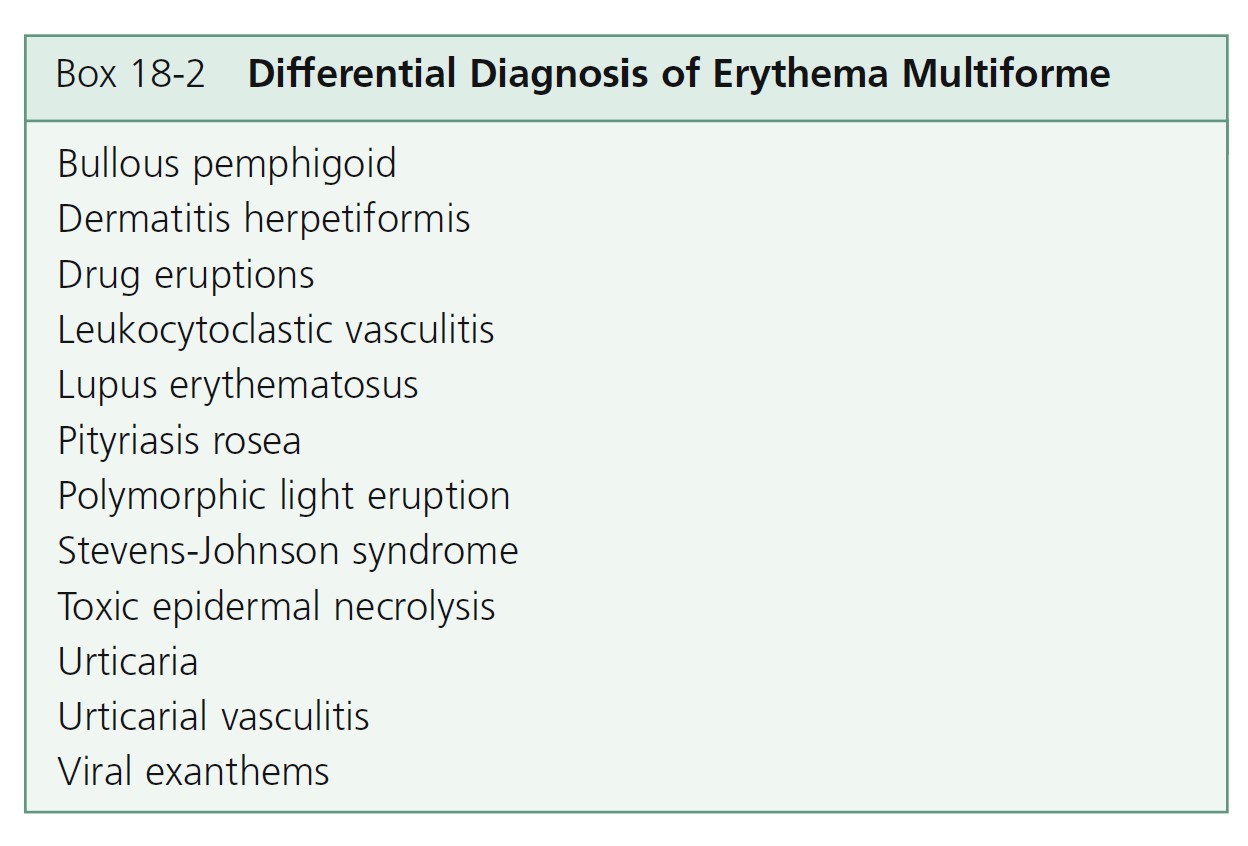

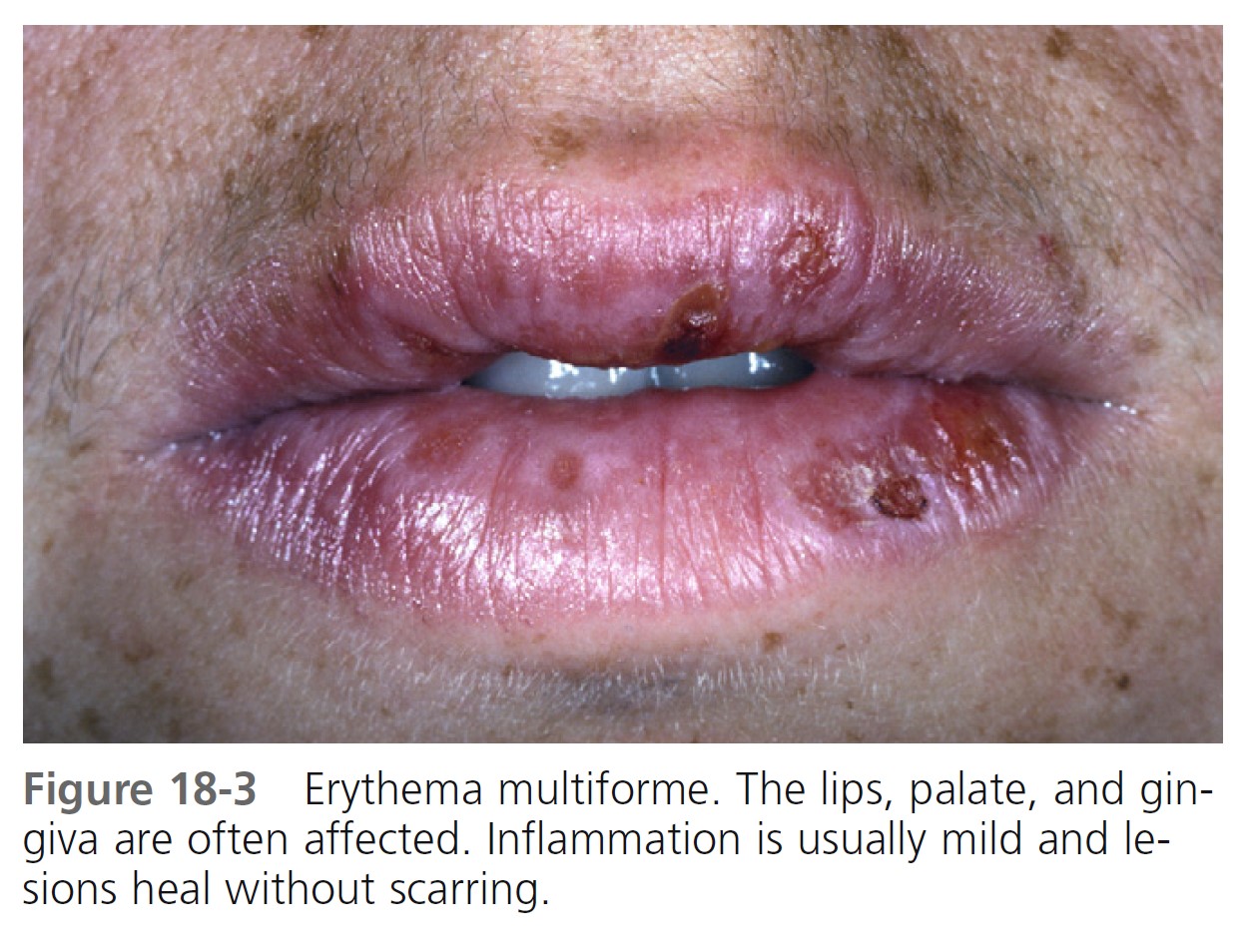

The prodromal symptoms, morphologic configuration of the lesions, and intensity of systemic symptoms vary. Milder forms of the disease may be preceded by malaise, fever, or itching and burning at the site where the eruption will occur. The cutaneous eruptions are most distinctive, and classification is based on their form. Mucosal lesions may occur in up to 70% of cases. The most common sites are the lips and buccal mucosa. The differential diagnosis is listed in Box 18-2 .

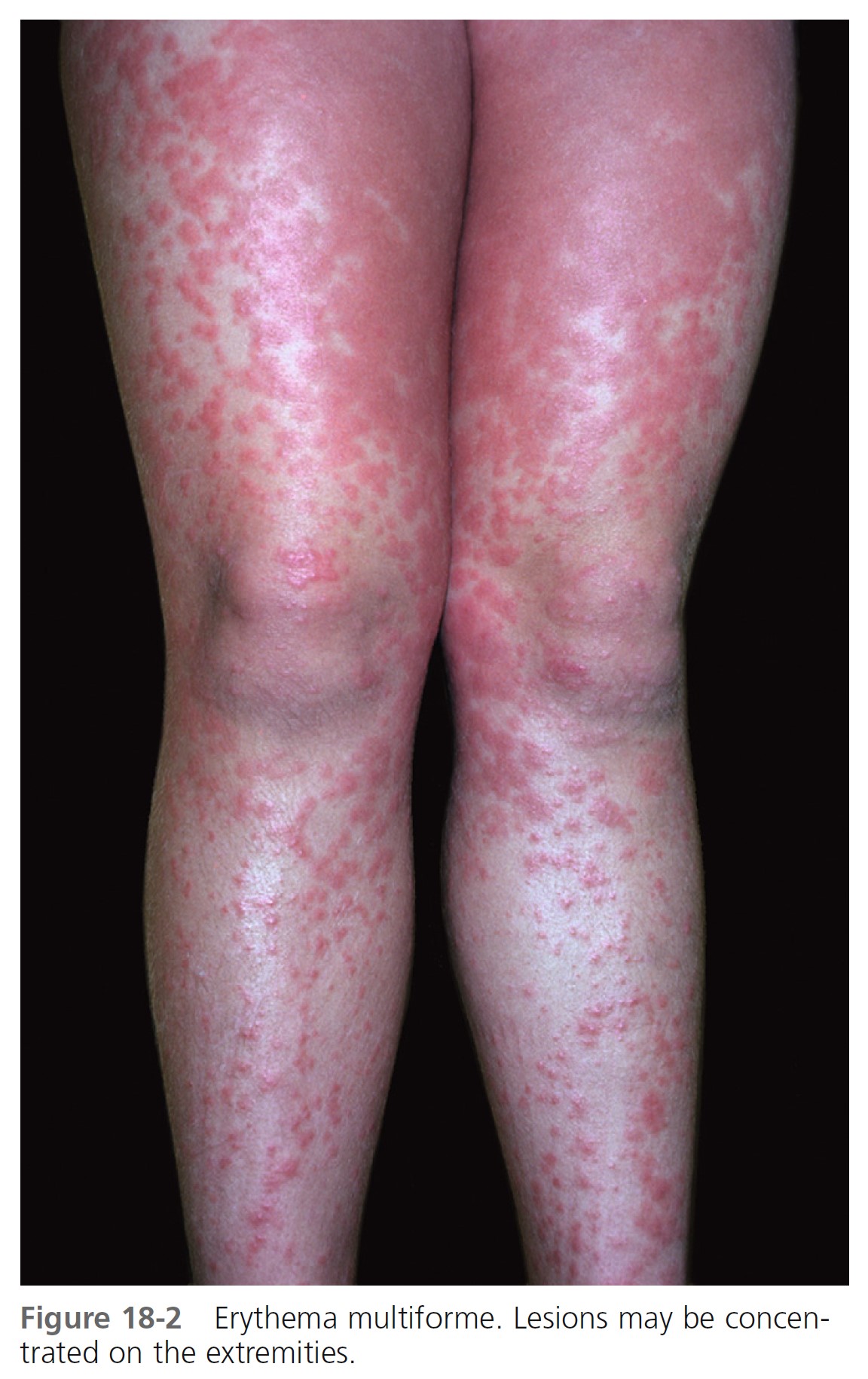

TARGET LESIONS AND PAPULES. Target lesions and papules are the most characteristic eruptions. Dusky red, round maculopapules appear suddenly in a symmetric pattern on the backs of the hands and feet and the extensor aspect of the forearms and legs. The trunk may be involved in more severe cases. Early lesions itch, burn, or are asymptomatic. The diagnosis may not be suspected until the nonspecific early lesions evolve into target lesions during a 24- to 48-hour period ( Figures 18-2 to 18-4 ). The classic “iris” or target lesion results from centrifugal spread of the red maculopapule to a circumference of 1 to 3 cm as the center becomes cyanotic, purpuric, or vesicular. The mature target lesion consists of two distinct zones: an inner zone of acute epidermal injury with necrosis or blisters and an outer zone of erythema. There may be a middle zone of pale edema. Partially formed targets with annular borders or target lesions on the palms and soles are less distinctive and clinically resemble urticaria. Individual lesions heal in 1 or 2 weeks without scarring but with hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation, while new lesions appear in crops.

Bullae and erosions may be present in the oral cavity. The entire episode lasts for approximately 1 month.

LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and moderate leukocytosis are found in the more severe cases. Biopsy is performed for atypical cases. Direct immunofluorescence may be needed to exclude other bullous diseases.

TREATMENT. Mild cases are not treated. Patients with many target lesions respond rapidly to a 1- to 3-week course of prednisone. Prednisone (40 to 80 mg/day) is continued until control is achieved and is then tapered rapidly in 1 week. Treatment with prednisone can successfully abort a recurrence. Oral acyclovir (400 mg twice a day) used continually prevents herpes-associated recurrent EM in many cases ( Figure 18-5 ). Herpes-associated EM is not prevented if oral acyclovir is administered after a herpes simplex recurrence is evident, and it is of no value after EM has occurred. Acyclovir has been used by some patients continually for years without any apparent ill effects. Recurrent erythema multiforme patients should receive oral acyclovir (where HSV is not an obvious precipitating factor) for 6 months. Valacyclovir and famciclovir are absorbed better than acyclovir and may be used for patients who do not respond to acyclovir. If these treatments fail, dapsone or antimalarial drugs may be tried. Partial or complete suppression was evident in patients treated with dapsone (100 to 150 mg daily). Azathioprine was used successfully in patients with severe disease for whom all other

treatments had failed. The response to treatment was dose dependent (100 to 150 mg daily). The condition recurred on discontinuation of therapy.

Patients with chronic recurrent EM were given thalidomide 100 mg/day after other treatments had failed, particularly acyclovir and prednisone. Thalidomide was given at the beginning of an episode. The duration of the episodes was reduced by 11 days on average. Patients with frequent recurrent EM were given continuous treatment. Lesions disappeared within 5 to 8 days, and remission was maintained with low-dose treatment.

STEVENS-JOHNSON SYNDROME/ TOXIC EPIDERMAL NECROLYSIS SPECTRUM OF DISEASE

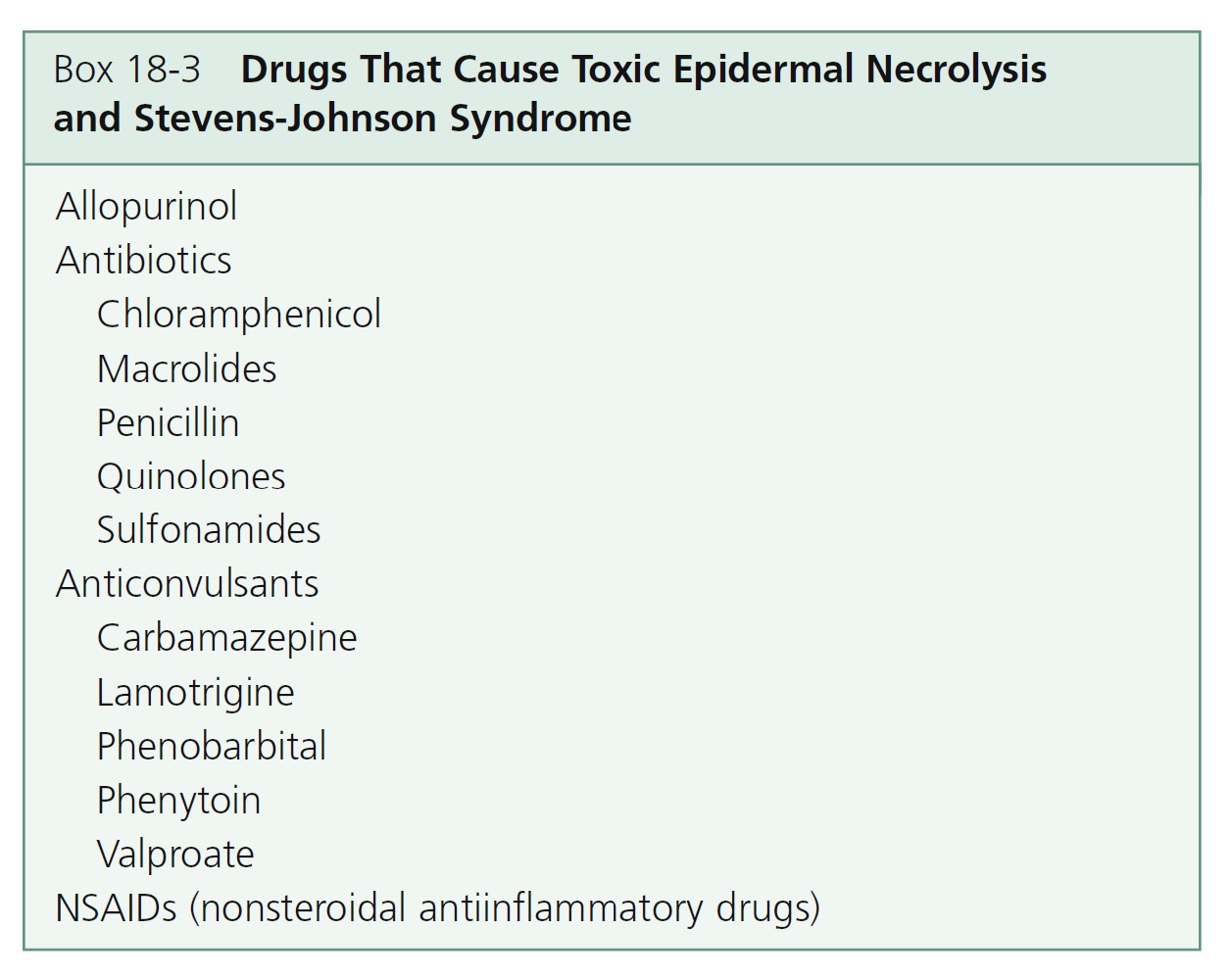

INTRODUCTION. SJS and TEN are rare diseases with an annual incidence of 1.2 to 6 and 0.4 to 1.2 per million persons, respectively. Patients at greatest risk are those with slow acetylator genotypes, immunocompromised patients (e.g., HIV infection, lymphoma), and patients with brain tumors who are undergoing radiotherapy and receiving antiepileptics. Drugs are implicated in over 95% of patients with TEN. The etiology of SJS is less well-defined as about 50% of reported SJS cases are claimed to be drug related. The most frequently implicated drugs are shown in Box 18-3 .

Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis have traditionally been considered the most severe forms of erythema multiforme (EM). It was proposed that EM major is distinct from SJS and TEN on the basis of clinical criteria. The proposed concept is to separate an EM spectrum from an SJS/TEN spectrum. EM, characterized by typical target lesions, is a postinfectious disorder, often recurrent but with low morbidity. The second spectrum (SJS/TEN), characterized by widespread blisters and purpuric macules, is usually a severe drug-induced reaction with high morbidity and a poor prognosis. In this concept, SJS and TEN might be only types of the same drug-induced process that vary in severity.

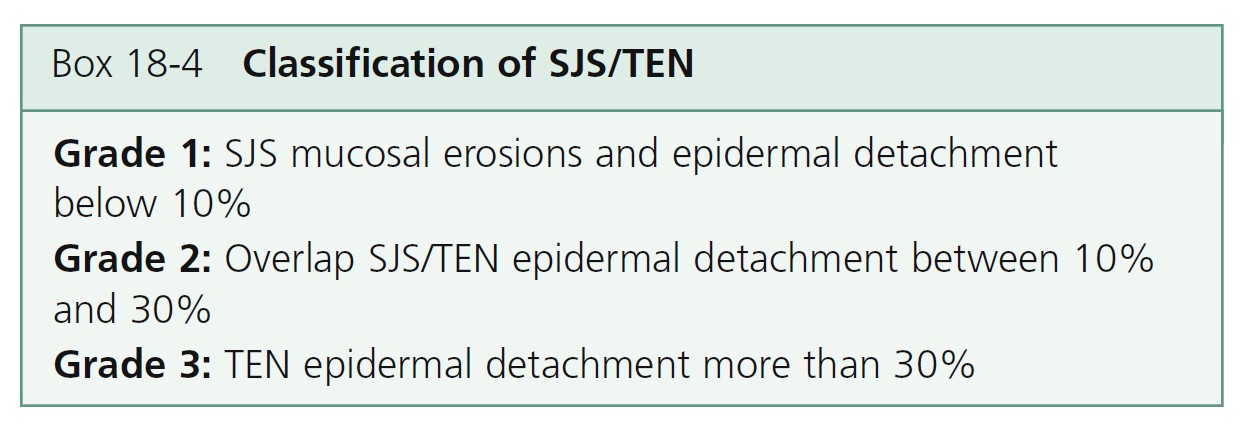

A three-grade classification has been proposed and the degree of cutaneous involvement in TEN and SJS is shown in Box 18-4 .

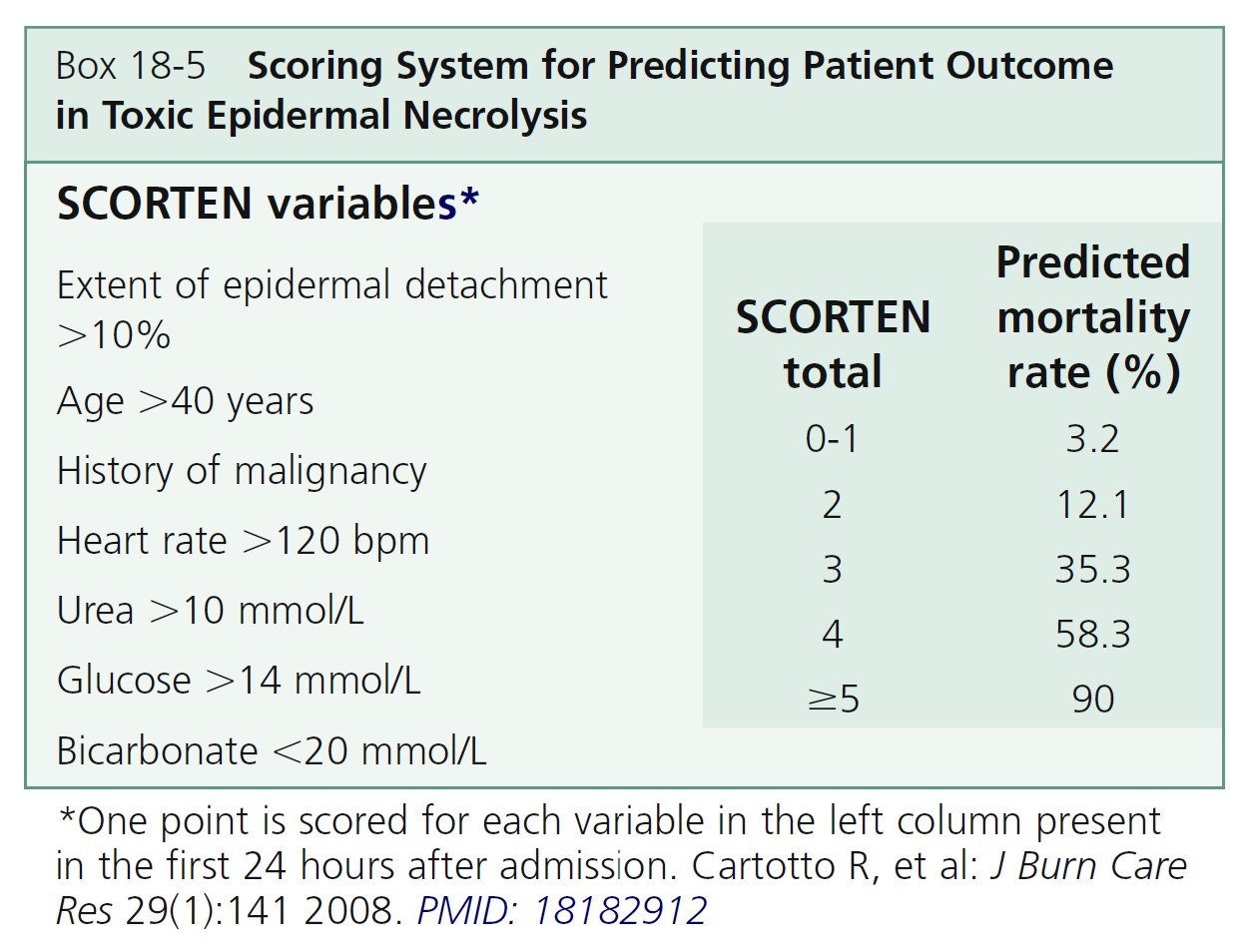

PREDICTING PATIENT OUTCOME. A scoring system for TEN named the SCORTEN severity of illness score was developed to predict patient mortality ( Box 18-5 ). Seven parameters are given one point if positive and zero if negative. Computing the sum of the scores results in a “SCORTEN” ranging from 0 to 7, with a score of 0 or 1 predicting a mortality of 3.2%, and a score of 5 or above predicting a mortality of greater than 90%.

EVOLUTION OF LESIONS IN SJS AND TEN. Skin lesions appear on the trunk first and then spread to the neck, face, and proximal upper extremities. The distal portions of the arms are usually spared, but the palms and soles can be an early site of involvement. Erythema and erosions of the buccal, ocular, and genital mucosa are present in more than 90% of patients. The epithelium of the respiratory tract is involved in 25% of cases of TEN, and gastrointestinal lesions can also occur. Skin lesions are tender, and mucosal erosions are painful. First, lesions appear as dusky-red or purpuric macules that have a tendency to coalesce. The macular lesions assume a gray hue. This process can occur in hours or take several days. The necrotic epidermis then detaches from the dermis and fluid fills the space to form blisters. The blisters break easily (flaccid) and extend sideways with slight thumb pressure as more necrotic epidermis is displaced laterally (Nikolsky’s sign). The skin looks like wet cigarette paper as it is slid away by pressure to reveal large areas of bleeding dermis.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome

Vesiculobullous disease of the skin, mouth, eyes, and genitals is called Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The disease occurs most often in children and young adults. The cutaneous eruption is preceded by symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection. A harsh, hacking cough and patchy changes on chest radiograph examination indicate pulmonary involvement. Patients with limited disease may be weak and lethargic, but the prognosis is good with conservative treatment. Mortality approaches 10% for patients with extensive disease. Fever is high during the active stages. Oral lesions may continue for months.

INITIAL SYMPTOMS. Initial symptoms are fever, stinging eyes, and pain with swallowing. They precede cutaneous manifestations by 1 to 3 days.

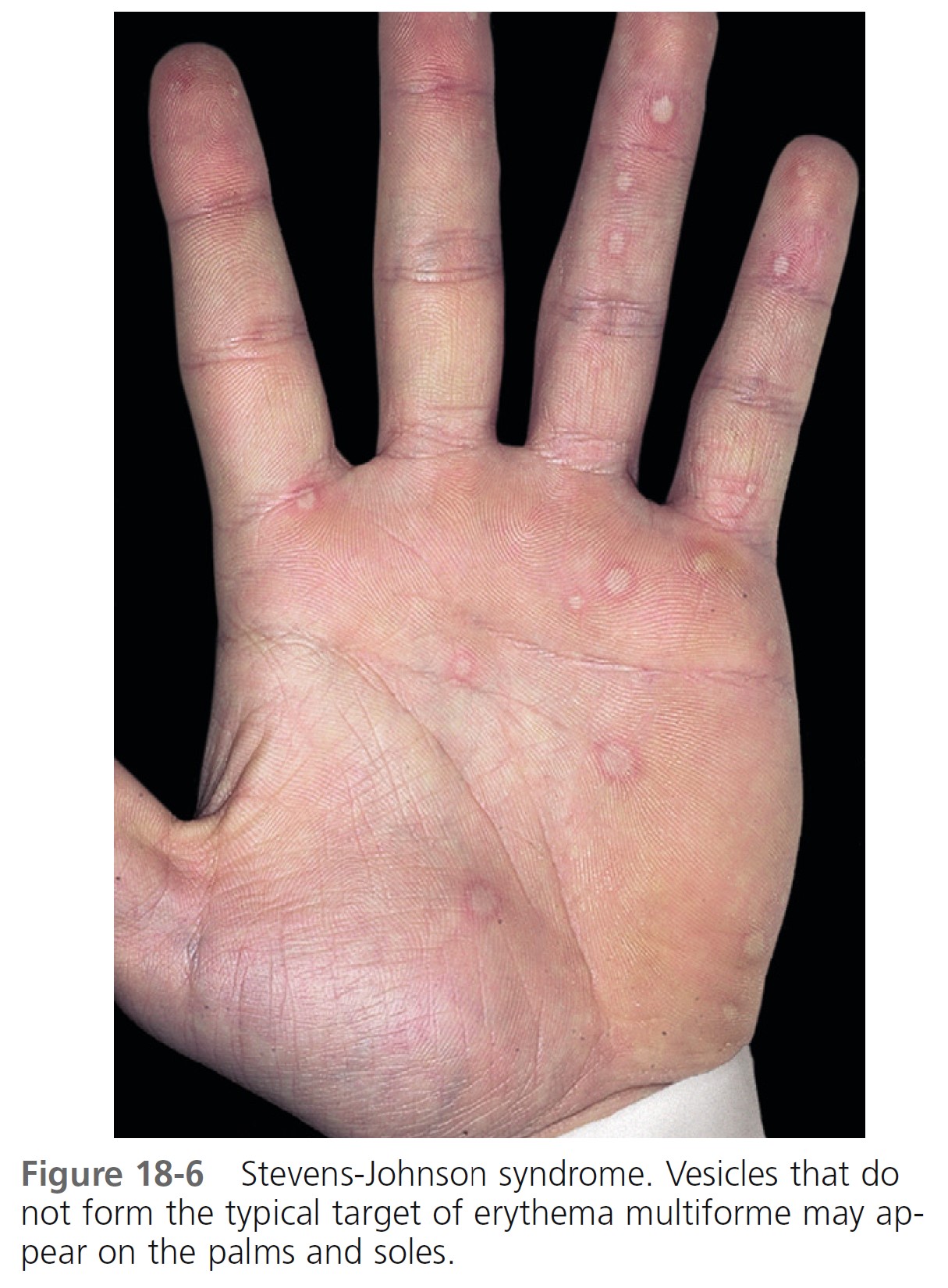

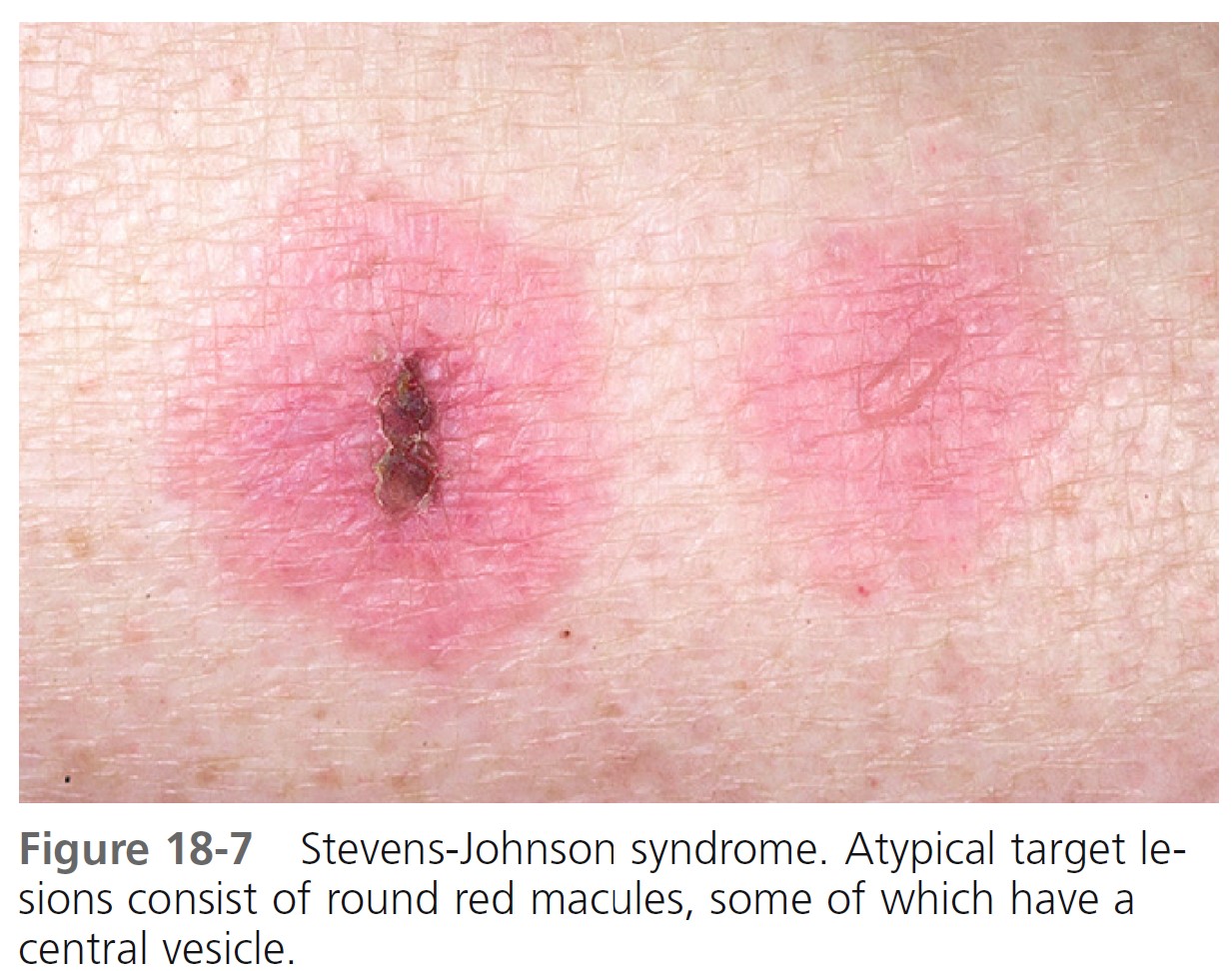

SKIN LESIONS. Skin lesions in SJS are flat, atypical targets, or purpuric maculae that are widespread or distributed on the trunk first and then spreading to the neck, face, and proximal upper extremities. The palms and soles may be an early site of involvement ( Figures 18-6 and 18-7 ).

This is in contrast to the lesions in erythema multiforme, which consist of typical or raised atypical targets or raised edematous papules that are located on the extremities and/or the face. New crops of lesions appear, but the disease is self-limited and resolves in approximately 1 month if there are no complications.

MUCOSAL LESIONS. Bullae occur suddenly 1 to 14 days after the prodromal symptoms, appearing on the conjunctivae and mucous membranes of the nares, mouth ( Figure 18-8 ), anorectal junction, vulvovaginal region, and urethral meatus. Ulcerative stomatitis leading to hemorrhagic crusting is the most characteristic feature.

OCULAR SYMPTOMS. Corneal ulcerations may lead to blindness. Severe ocular mucosal injury that occurs in Stevens-Johnson syndrome may be a precipitating factor in the development of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, a chronic, scarring inflammation of the ocular mucosae that can lead to blindness. The time between the onset of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and cicatricial pemphigoid ranges from a few months to 31 years.

ETIOLOGY. Drugs are the most common cause (see Box 18-3 ). The disease occurs most often in patients treated for seizure disorders. Upper respiratory tract infection, Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, and herpes simplex virus infection are all implicated. Possible causes should be sought diligently so that recurrences can be avoided.

DIAGNOSIS. A skin biopsy should be performed if the classic lesions are not present. Direct immunofluorescence may be helpful in nontypical cases.

TREATMENT. The use of corticosteroids remains controversial. A study of children suggests that treatment with systemic corticosteroids may be associated with delayed recovery and significant side effects. Other studies conclude that corticosteroids are beneficial and may be lifesaving. Many physicians presented with a sick child who has extensive cutaneous, ocular, and oral lesions elect to treat with oral steroids; most often prednisone (20 to 30 mg twice a day) is given until new lesions no longer appear; it is then tapered rapidly.

Itching can be controlled with antihistamines. Cutaneous blisters are treated with cool, wet Burow’s compresses. Topical steroids should not be applied to eroded areas. Papules and plaques may respond to group II to V topical steroids. Frequent rinsing with lidocaine hydrochloride (Xylocaine Viscous) may relieve oral symptoms. Patients may tolerate only a liquid or soft diet. Ocular involvement is monitored by an ophthalmologist to minimize conjunctival scarring. Antiseptic eye drops and separation on synechiae are required. Vitamin A administered topically and systemically was reported to be effective for lacrimal hyposecretion. Secondary infection is treated with oral antibiotics. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with herpes simplex virus may be prevented by early use of acyclovir and prednisone.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is initially seen with Stevens-Johnson-like mucous membrane disease and progresses to diffuse, generalized detachment of the epidermis through the dermoepidermal junction. This full thickness loss of the epidermis results in a high death rate. Fluid loss is not a major problem; death is usually caused by overwhelming sepsis originating in denuded skin or lungs. TEN is rare, occurring in 1.3 cases per million persons per year.

The death rate is 1% to 5% for Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and 34% to 40% for TEN. Mortality is not affected by the type of drug responsible. In contrast to previous series, today there is a high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection among patients with TEN. This high rate of HIV infection is linked to an increased use of sulfonamides—mainly sulfadiazine—in these patients. TEN may occur after bone marrow transplantation. It seems to be related to a drug reaction to sulfonamides as often as to acute graft-versus-host disease.

TOXIC EPIDERMAL NECROLYSIS VS. STAPHYLOCOCCAL SCALDED SKIN SYNDROME. This life-threatening disease is similar in appearance to staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), which is induced by a staphylococcal toxin. The split in SSSS, however, is high in the epidermis, just below the stratum corneum, permitting rapid healing of the epidermis without danger of infection. The diagnosis of either TEN or SSSS can be made rapidly by examination of a skin biopsy by frozen section technique.

PATHOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS. Histologically there is an early mild interface dermatitis that evolves into full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis. Keratinocytes from patients with TEN were found to undergo extensive apoptosis. There is subepidermal blister formation, keratinocyte necrosis, and a sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate around superficial dermal blood vessels. Lymphopenia is frequently documented. Cytotoxic T cells may contribute to the pathogenesis of blister formation by causing degeneration and necrosis of drug-altered keratinocytes.

ETIOLOGY. The causes of TEN are the same as those of Stevens-Johnson syndrome, but drugs are most frequently implicated in TEN. The reaction is independent of dosage. Culprit drugs include antibiotics (40%), anticonvulsants (11%), and analgesics (5% to 23%). Developing countries have a higher incidence of reactions to antituberculous drugs. The most frequent underlying diseases justifying drug treatment are infections (52.7%) and pain (36%). Challenge tests are absolutely contraindicated in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. TEN and other severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions may be linked to an inherited defect in the detoxification of drug metabolites. In a few predisposed patients, a drug metabolite may bind to proteins in the epidermis and trigger an immune response, leading to immunoallergic cutaneous adverse drug reaction.

MEDICATIONS. The use of antibacterial sulfonamides, anticonvulsant agents, oxicam NSAIDs, allopurinol, chlormezanone, and corticosteroids is associated with large increases in the risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis (see Box 18-3 ). The excess risk of these drugs does not exceed 5 cases per million users per week. The risk of developing TEN from antiepileptic drugs is highest in the first 8 weeks after onset of treatment.

The following drugs are most commonly implicated:

Acetaminophen

Allopurinol

Aminopenicillins

Carbamazepine

Cephalosporins

Chlormezanone

Corticosteroids

NSAIDs

Phenobarbital

Phenytoin

Quinolones

Sulfonamides

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Valproic acid

PRODROMAL SYMPTOMS. Fever is the most frequent prodromal symptom. Symptoms suggestive of an upper respiratory tract infection, such as headache and sore throat, usually precede the appearance of skin lesions by 1 or 2 weeks. Stomatitis, conjunctivitis, and pruritus occur 1 to 2 days before the onset of the rash.

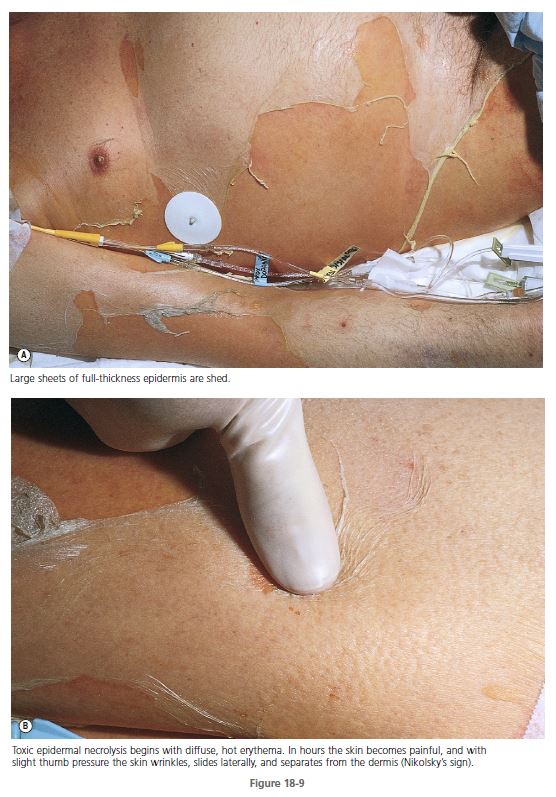

SKIN. TEN begins with diffuse, hot erythema covering wide areas. In hours the skin becomes painful, and with slight thumb pressure the skin wrinkles, slides laterally, and separates from the dermis ( Figures 18-9 and 18-10 ). This ominous sign (Nikolsky’s sign) heralds the onset of a life-threatening event. Small blisters and large bullae may appear. Nonerythematous skin usually remains intact, and the scalp is spared.

MUCOUS MEMBRANES. Inflammation, blistering, and erosion of the mucosal surfaces, especially the oropharynx, are early and characteristic findings. The vaginal tract epithelium frequently blisters and erodes. Pain and erosion of oral mucous membranes interfere with oral intake, and nasogastric or duodenal tube feeding is often required. The rest of the gastrointestinal tract functions normally if sepsis does not occur.

EYES. Severe eye involvement is a constant feature. Purulent conjunctivitis leads to swelling, crusting, and ulceration with pain and photophobia. Complications include conjunctival erosions with subsequent revascularization, fibrous adhesions, and corneal ulceration and blindness. Photophobia, mucinous discharge, and decreased visual acuity may last for years.

RESPIRATORY TRACT. Involvement of bronchial epithelium was noted in 27% of cases and must be suspected when dyspnea, bronchial hypersecretion, normal chest radiograph, and marked hypoxemia are present during the early stages of toxic epidermal necrosis. Bronchial injury indicates a poor prognosis. Life-threatening acute respiratory decompensation requiring ventilatory support and long-term pulmonary function abnormalities may occur. Patients should be closely monitored for pulmonary complications. Bronchopneumonia occurs in 30% of reported cases and is the cause of death in many cases. Many patients require intubation or ventilatory support. Respiratory failure can occur, with mucus retention and sloughing of the tracheobronchial mucosa.

INFECTION. Septicemia and gram-negative pneumonia are the most common causes of death. The lungs and denuded skin are the common portals of entry. The incidence of positive blood culture results is very high when central venous lines are used. Intravenous lines are changed or discontinued if it is probable that they are the source of positive blood culture findings. The urethra is often involved, but the use of Foley catheters can be avoided in many cases.

FLUID AND ELECTROLYTE LOSS. Fluid loss in TEN is not as severe as it is in burn patients, but significant losses can occur if grafts are not applied. Apparently, the acute phase reactants that create massive edema after thermal injury are not released in TEN.

OTHER COMPLICATIONS. Leukopenia of uncertain cause may occur. Toxins (e.g., from absorbed silver sulfadiazine) or immune complexes may be the cause. In one series, renal involvement consisting of hematuria, proteinuria, and elevated serum creatine level occurred in 50% of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

TREATMENT

Systemic steroids. The use of systemic steroids is still controversial, but most authors recommend that steroids not be used.

Steroids cannot prevent the occurrence of TEN, even in high dosages. Patients treated for other diseases with glucocorticosteroids for at least 1 week before the first dermatologic sign of TEN showed no difference in mortality compared with untreated patients. This suggests that steroids do not protect the epidermis from drug-induced keratolysis. Improved survival rates have been reported when patients with TEN have been treated without steroids.

Cyclosporine. Patients with TEN treated with cyclosporin A (3 to 4 mg/kg per day) without other immunosuppressive agents experienced rapid reepithelialization and a low death rate. This regimen was more effective than a series of patients previously treated with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids.

Cyclophosphamide. In one study, cyclophosphamide (100 to 300 mg/day intravenously for 5 days) stopped the blistering, pain, and erythema in a few days. Reepithelialization rapidly occurred in 4 to 5 days. Cyclophosphamide inhibits cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Plasma exchange and immunoglobulins. Plasma exchange resulted in complete remission in two series. Plasmapheresis is a safe intervention in extremely ill patients and may reduce the death rate. The efficacy of IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) is yet to be defined.

Burn center treatment. TEN has pathophysiologic similarities to partial-thickness burn injury. The management of major fluid and electrolyte derangements, the intensive nutritional support, and the management of extensive cutaneous injuries with ready access to biologic and semisynthetic wound dressings are best accomplished in a multidisciplinary burn center.

The current trend toward prolonged treatment in outside facilities before referral to a burn center is detrimental to the care of patients with TEN. The overall rate of bacteremia, septicemia, and mortality is significantly reduced with early (≤7 days) referral to a regional burn center.

Separation at the junction of the dermis and epidermis leaves totally viable dermis and intact skin appendages. If the dermis can be protected from toxic detergents, salves, or desiccation, rapid resurfacing by proliferation of epithelium from the skin appendages will occur in approximately 14 days without scarring. Silver sulfadiazine and mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon) delay epithelialization.

ERYTHEMA NODOSUM

Erythema nodosum (EN) is a nodular erythematous eruption that is usually limited to the extensor aspects of the extremities. EN represents a hypersensitivity reaction to a variety of antigenic stimuli and may be observed in association with several diseases (infections, immunopathies, malignancies) and during drug therapy (with halides, sulfonamides, oral contraceptives). Approximately 55% of cases are idiopathic. Laboratory tests show no specific abnormalities except those related to an underlying disease. Familial EN is reported, with affected family members showing a common haplotype. The incidence has decreased in the antibiotic era. EN is seen more frequently in females. The peak incidence occurs between the ages of 18 and 34 years. The female to male ratio is 5:1.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COURSE. Prodromal symptoms of fatigue and malaise or symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection precede the eruption by 1 to 3 weeks. The clinical picture is that of a nonspecific systemic illness, with low-grade fever (60%), malaise (67%), arthralgias (64%), and arthritis (31%). Pulmonary hilar adenopathy may develop as part of the hypersensitivity reaction of EN and is seen in cases with diverse causes.

JOINT SYMPTOMS. Arthralgia occurs in more than 50% of patients and begins during the eruptive phase or precedes the eruption by 2 to 8 weeks. Symptoms may disappear in a few weeks or persist for 2 years, but they always resolve without destructive joint changes. Testing for rheumatoid factor is negative. Joint symptoms consist of erythema, swelling, and tenderness over the joint, sometimes with effusions; arthralgia and morning stiffness, most commonly in the knee, but any joint may be affected; and polyarthralgia lasting for days.

SKIN ERUPTION. The eruptive phase begins with flu like symptoms of fever and generalized aching. The characteristic lesions begin as red, node like swellings over the shins; as a rule, both legs are affected. Similar lesions may appear on the extensor aspects of the forearms, thighs, and trunk ( Figure 18-11 ). The border is poorly defined, with size varying from 2 to 6 cm. Lesions are oval, and their long axis corresponds to that of the limb. During the first week the lesions become tense, hard, and painful; during the second week they become fluctuant, as in an abscess, but never suppurate. The color changes in the second week from bright red to bluish or livid; as absorption progresses, it gradually fades to a yellowish hue, resembling a bruise; this disappears in 1 or 2 weeks as the overlying skin desquamates. The individual lesions last approximately 2 weeks, but new lesions sometimes continue to appear for 3 to 6 weeks. Aching of the legs and swelling of the ankles may persist for weeks. The condition may recur for months or years.

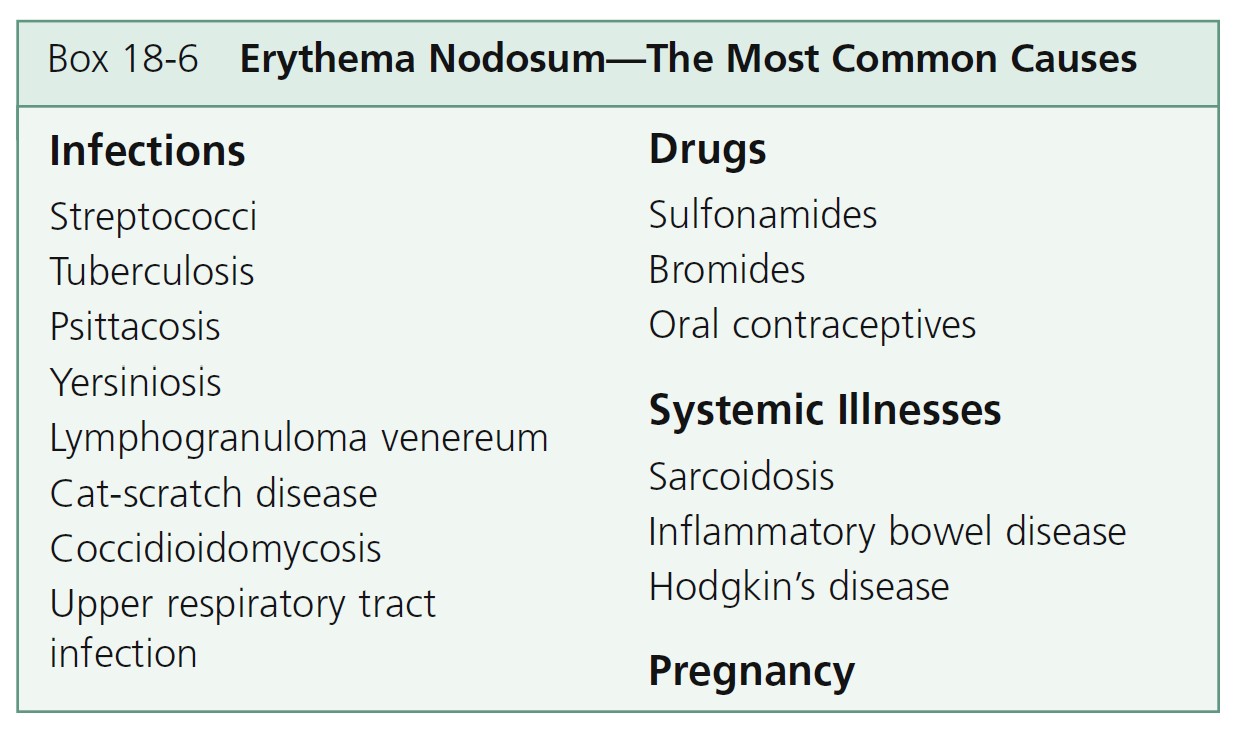

PATHOGENESIS AND ETIOLOGY. Erythema nodosum is probably a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to a variety of antigens; circulating immune complexes have not been found in idiopathic or uncomplicated cases. EN is a reaction pattern elicited by many different diseases ( Box 18-6 ). In one large series, 32.5% of cases were idiopathic. The most common cause today is streptococcal infection and noninfectious inflammatory diseases in children and streptococcal infection and sarcoidosis in adults. Dental treatment and the possible presence of infectious dental foci should be considered in the differential diagnosis. EN is reported following dental treatment associated with gingival bleeding or because of infectious dental foci. Many other causes of EN have been reported; most consist of single histories. New etiologies continue to be described.

FUNGAL INFECTIONS. Coccidioidomycosis (San Joaquin Valley fever) is the most common cause of EN in the West and Southwest United States. In approximately 4% of males and 10% of females, the primary fungal infection, which may be asymptomatic or involve symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection, is followed by the development of EN. The lesions appear when the skin test result becomes positive, 3 days to 3 weeks after the end of the fever caused by the fungal infection. Dissemination and serious disease develop more often in pregnant patients with coccidioidomycosis than in the general population. Erythema nodosum appears to be a salient marker of a positive outcome for pregnant patients, more so than for the general population.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE. Inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis and regional ileitis may trigger EN, usually during active disease with symptoms of abdominal complaints and diarrhea. The mean duration of chronic ulcerative colitis before the onset of EN is 5 years, and the EN is controlled with adequate therapy of the colitis. Yersinia enterocolitica, a gram-negative bacillus that causes acute diarrhea and abdominal pain, is a reported cause.

DRUGS. Sulfonamides, bromides, and oral contraceptives have been reported to cause EN. Several other drugs, such as antibiotics, barbiturates, and salicylates, are often suspected but seldom proved causes.

SARCOIDOSIS. EN occurs in up to 39% of cases of sarcoidosis and has also been observed in pregnant women. Seasonal clustering of sarcoidosis presenting with EN has been reported. This suggests a common environmental trigger in the etiology of sarcoidosis.

LÖFGREN’S SYNDROME. Löfgren’s syndrome is the association of erythema nodosum or periarticular ankle inflammation with unilateral or bilateral hilar or right paratracheal lymphadenopathy with or without pulmonary involvement. The mean age of onset is 37 years. Löfgren’s syndrome, which in most cases represents an acute variant of pulmonary sarcoidosis with benign course, is more frequent in females, especially during pregnancy and puerperium.

LYMPHOMA. EN should be considered as a warning signal of impending relapse in a patient with a history of Hodgkin’s disease. Patients in whom erythema nodosum was associated with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma have an extremely protracted course. Erythema nodosum associated with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma may precede the diagnosis of lymphoma by months.

DIAGNOSIS. Initial evaluation should include throat culture, antistreptolysin titer, chest radiograph, purified protein derivative skin test, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The ESR is elevated in all patients with EN. The white blood count is normal or only slightly increased. Patients with GI symptoms should have a stool culture for Y. enterocolitica, Salmonella, and Campylobacter pylori . Bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest radiograph examination does not establish the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, because hilar adenopathy occurs in EN produced by coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, streptococcal infections, and lymphoma, and as a nonspecific reaction in many cases. When the etiology is in doubt, blood should be serologically investigated from those bacterial, virologic, fungal, or protozooal infections more prevalent in the area.

BIOPSY. The clinical picture is characteristic in most cases, and a biopsy is not required. Histologic confirmation is desirable in atypical cases. An excisional rather than a punch biopsy is necessary to sample the subcutaneous fat adequately. Tissue sections show lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, granulomatous inflammation, and fibrosis in the septa of the subcutaneous fat; these are all features of a septal panniculitis.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS. In Weber-Christian panniculitis, localized areas of subcutaneous inflammation tend to occur on the thighs and trunk rather than on the lower legs. Lesions may suppurate and heal with atrophy and localized depressions. Superficial and deep thrombophlebitis and erysipelas must also be differentiated from EN.

TREATMENT. EN in most instances is a self-limited disease and requires only symptomatic relief with salicylates and bed rest. Indomethacin (250 mg three times daily) or naproxen (250 mg twice daily) may be more effective than aspirin. Cases that are recurrent, unusually painful, or long lasting require a more vigorous approach.

A supersaturated solution of potassium iodide (5 drops three times daily) in orange juice is started. Increase the dose by 1 drop per dose per day until the patient responds. Relief of lesional tenderness, arthralgia, and fever may occur in 24 hours. Most lesions completely subside within 10 to 14 days. However, potassium iodide is not effective for all patients with EN. Patients who receive medication shortly after the initial onset of EN respond more satisfactorily than those with chronic EN. Side effects include nasal catarrh and headache. Hyperthyroidism may occur with long-term use. Potassium iodide is contraindicated during pregnancy, because it can produce a goiter in the fetus.

Corticosteroids are effective but seldom necessary in self-limited diseases. Recurrence following discontinuation of treatment is common, and underlying infectious disease may be worsened.

There is limited experience with colchicine (0.6 to 1.2 mg twice daily), hydroxychloroquine (200 mg twice daily), and dapsone.

VASCULITIS

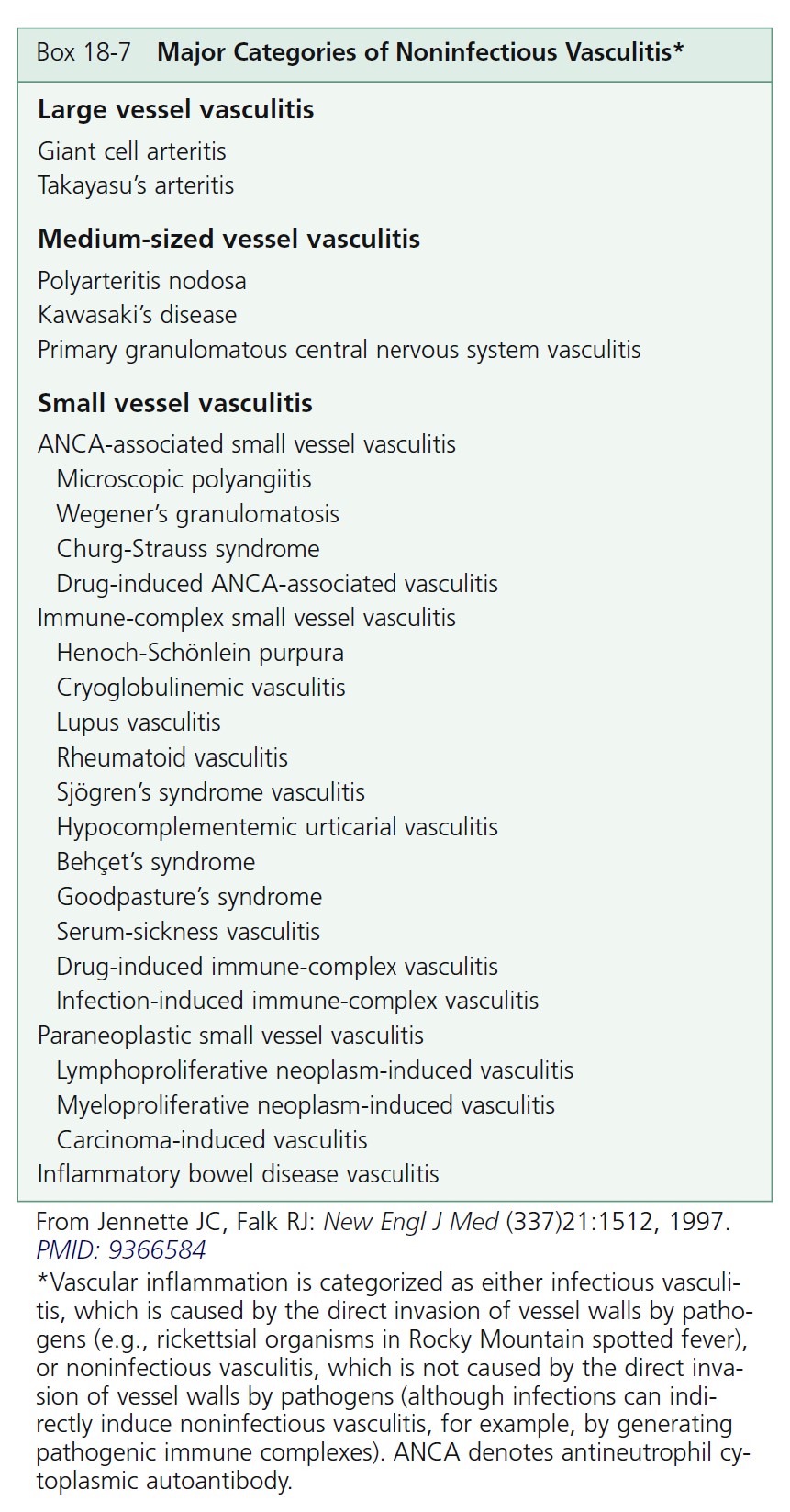

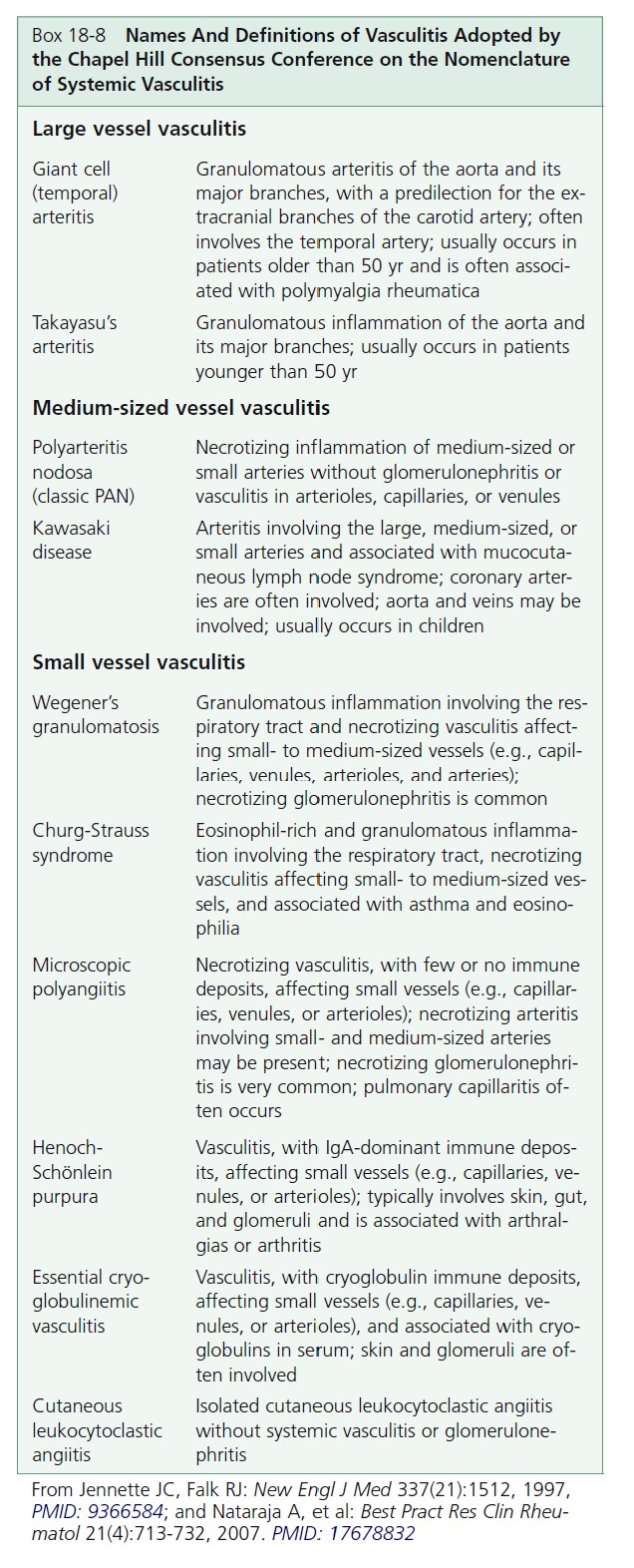

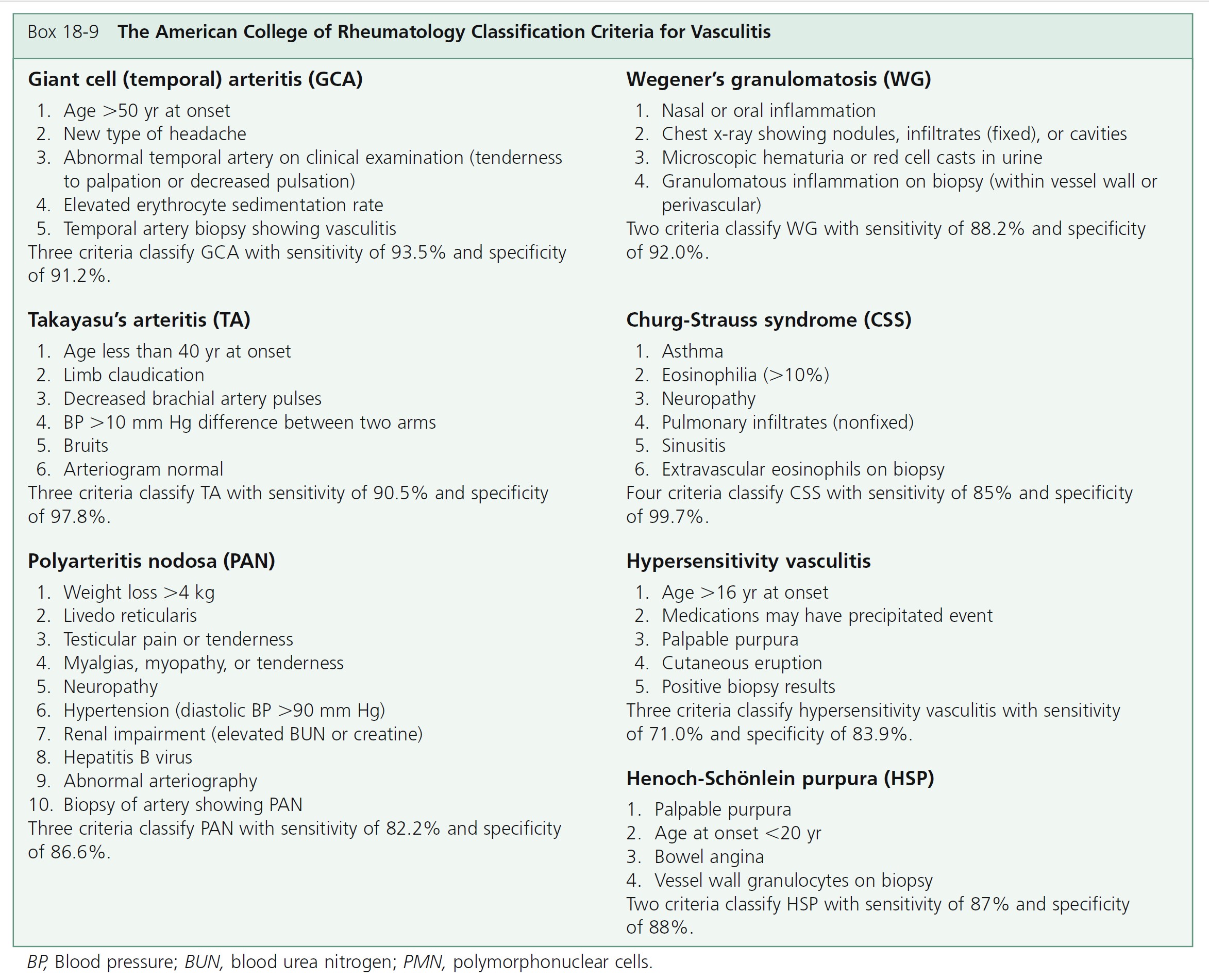

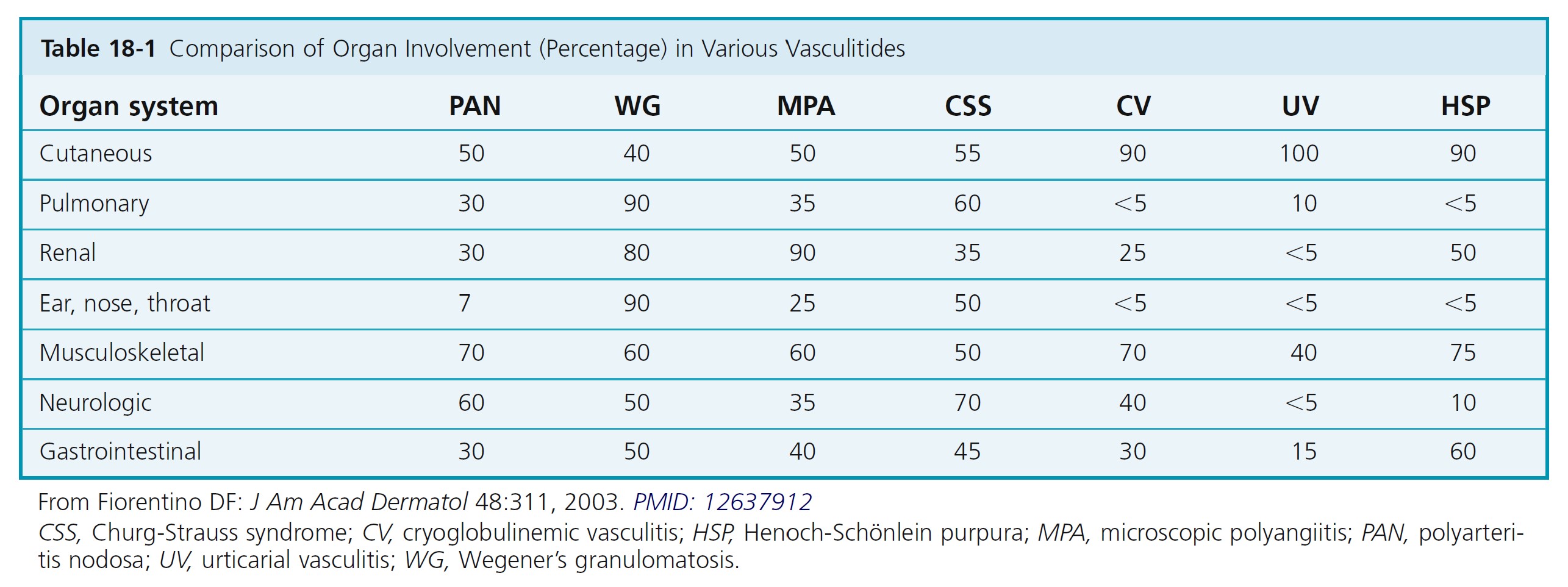

Cutaneous vasculitis encompasses a highly heterogeneous group of disorders of diverse etiology, pathogenesis, and clinical features ( Boxes 18-7 to 18-9 and Table 18-1 ).

CLASSIFICATION. Vasculitis, or angiitis, defined as inflammation of the vessel wall, is probably initiated by immune complex deposition. The cutaneous vasculitic diseases are classified according to the type of inflammatory cell within the vessel walls (neutrophil, lymphocyte, or histiocyte) and the size and type of blood vessel involved (venule, arteriole, artery, or vein). Some vasculitic diseases are limited to the skin; others involve vessels in many different organs.

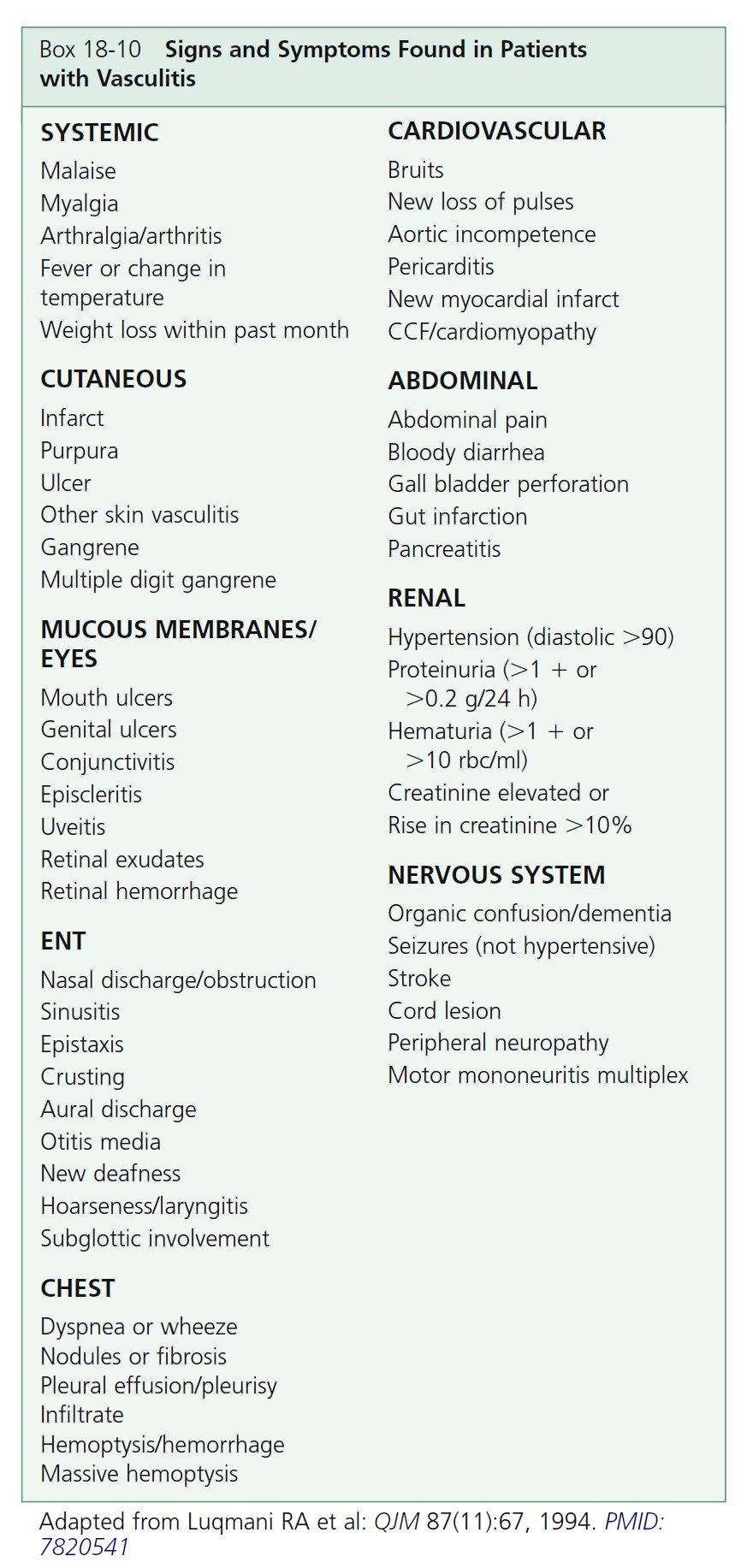

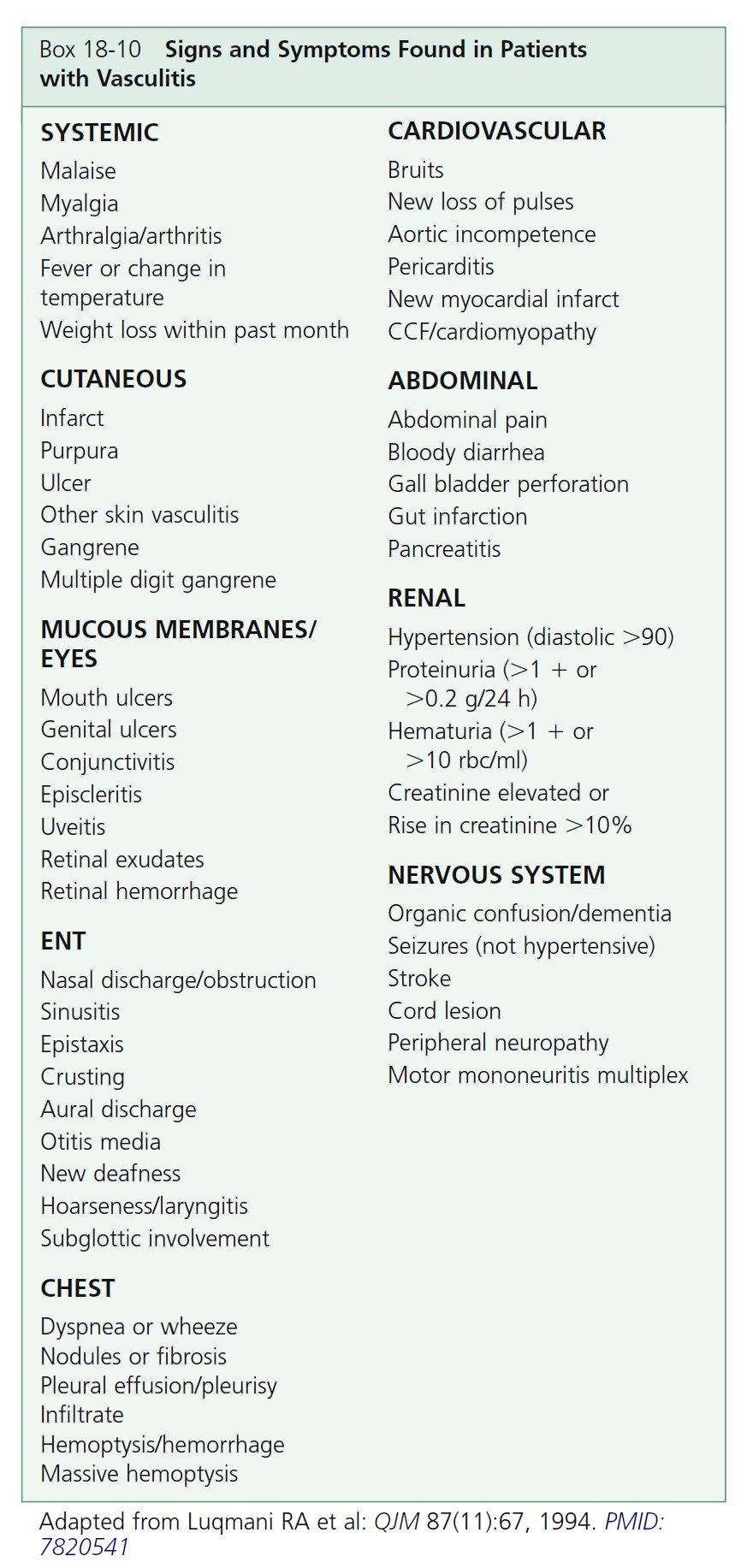

MULTISYSTEM DISEASE. A broad spectrum of symptoms is seen in the vasculitic syndromes ( Box 18-10 ). These symptoms and signs are suggestive or consistent with a diagnosis of systemic vasculitis. The presence of many symptoms means that there is no single pathognomonic feature of vasculitis. Recognizing patterns is important for early diagnosis. For example, a new-onset headache in a person over the age of 50 years with an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate should trigger a suspicion of giant cell arteritis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION. The clinical presentation varies with the size of the blood vessel involved and the intensity of the inflammation (see Box 18-8 and Figure 18-12 ). Small vessel vasculitis—arteriole, capillary, venule—most commonly affects the skin and rarely causes serious internal organ dysfunction, except when the kidney is involved.

There are numerous cutaneous diseases that histologically show some degree of vessel inflammation. Only those diseases that have inflammation severe enough to cause necrosis of vessel walls are discussed here. Necrotizing angiitis is the term given to this group of diseases. These diseases have clinical features that allow one to predict that vessel inflammation and necrosis are taking place and to

identify the size of vessel involved (see Table 18-1 ).

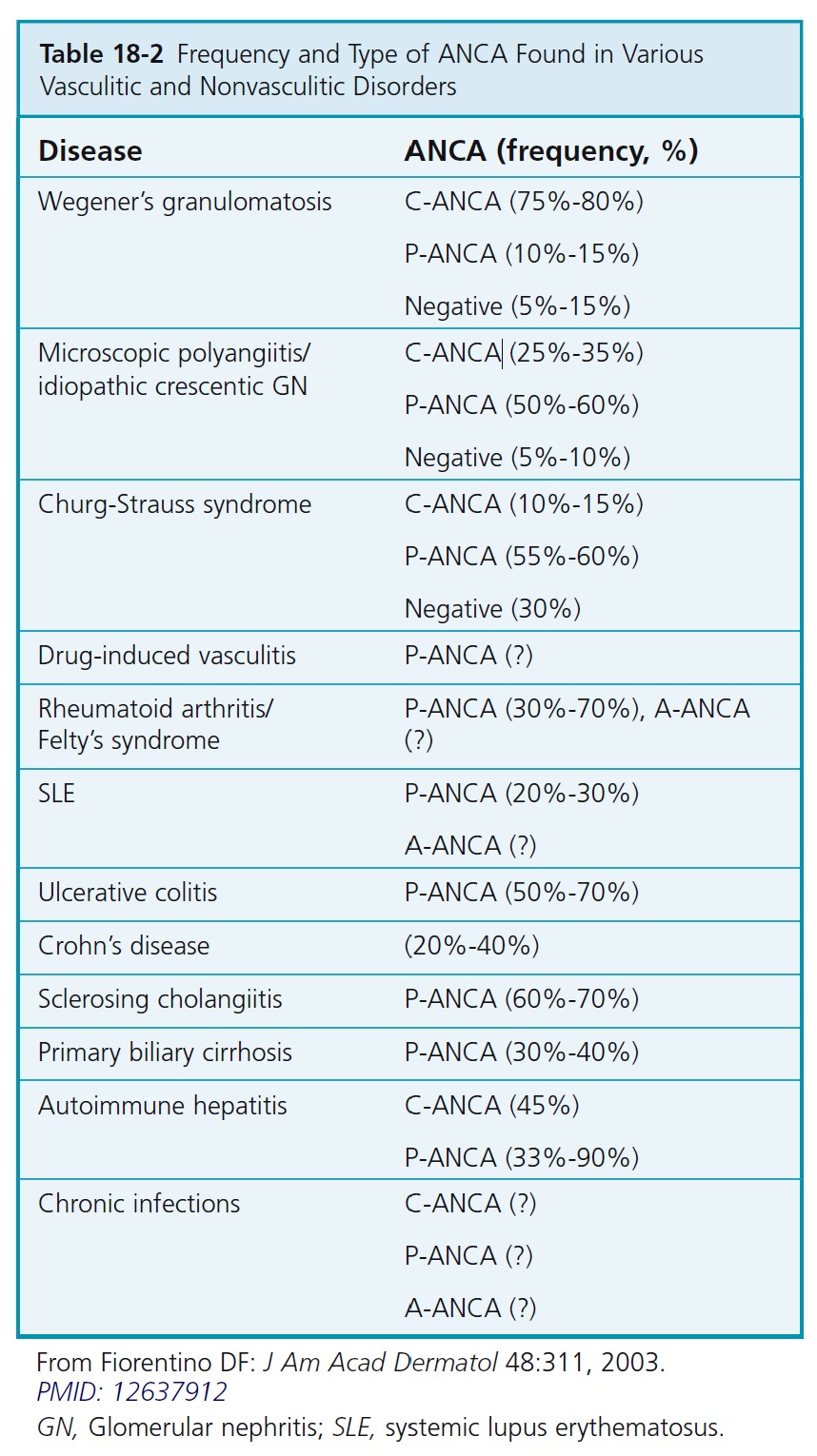

ANTINEUTROPHIL CYTOPLASMIC ANTIBODIES. The diagnosis and classification of vasculitis have been revolutionized by the discovery of serum antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCAs) ( Table 18-2 ). ANCAs are a serologic marker for many forms of necrotizing vasculitis. Use of ANCA testing provides a significant diagnostic advantage over reliance on biopsy findings alone in patients

whose differential diagnosis includes any of the vasculitic diseases. Two staining patterns may be identified using immunofluorescence (IFA) on ethanol-fixed neutrophils: either a diffuse granular staining of the cytoplasm (cytoplasmic, or C-ANCA) or concentration of fluorescence around the nucleus (perinuclear, or P-ANCA).

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody–associated vasculitis. ANCA-associated small vessel vasculitis is the most common primary systemic small vessel vasculitis in adults and includes three major categories: Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome. Most patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis have PR3-ANCA (cytoplasmic ANCA or C-ANCA); most patients with microscopic polyangiitis or Churg-Strauss syndrome have MPO-ANCA (perinuclear ANCA or P-ANCA). Approximately 10% of patients with typical Wegener’s granulomatosis or microscopic polyangiitis have negative assays for ANCA; therefore ANCA negativity does not rule out these diseases. The specificity of ANCA positivity is not absolute; a positive result is not diagnostic for an ANCA- associated vasculitis, especially if the result of an indirect immunofluorescence assay has not been confirmed by the more specific enzyme immunoassay (EIA) technique. Patients are usually screened with the indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) test. The EIA is performed when the IFA test result is positive to identify the antigen. A more comprehensive strategy would be to order the IFA and EIA.

A positive test result for C- or P-ANCA predicts a 96% probability that necrotizing vasculitis or crescentic glomerulonephritis will develop; a negative test result portends a 93% probability that the patient does not have these diseases. ANCAs are reliable monitors of disease activity because antibody titers decline when patients go into remission with effective immunosuppressive therapy and

increase with relapse.

VASCULITIS OF SMALL VESSELS

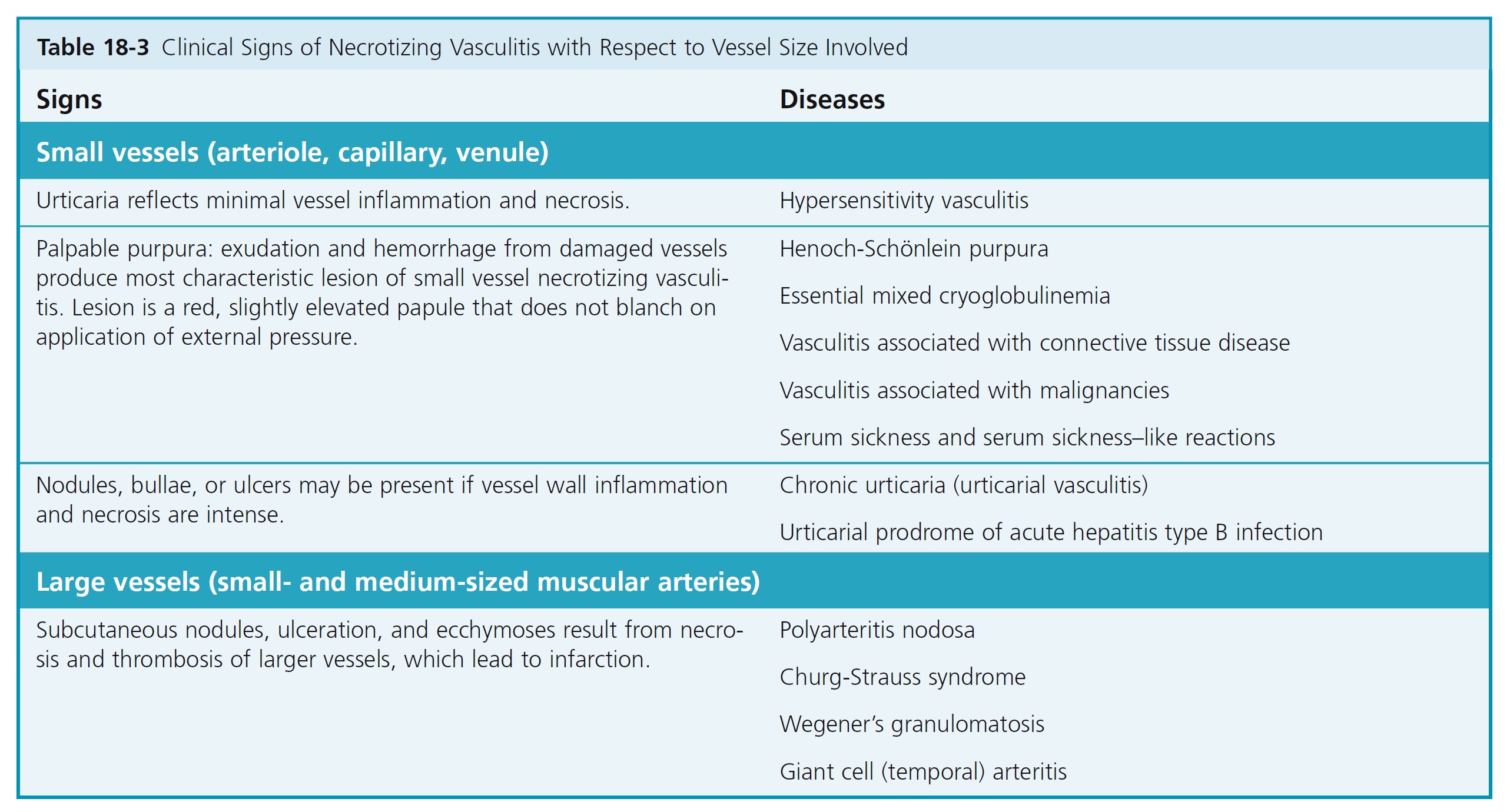

Most diseases characterized by necrotizing inflammation of small blood vessels have a number of features in common. Skin lesions reflect various degrees of small vessel necrotizing inflammation; the most common is palpable purpura ( Table 18-3 ).

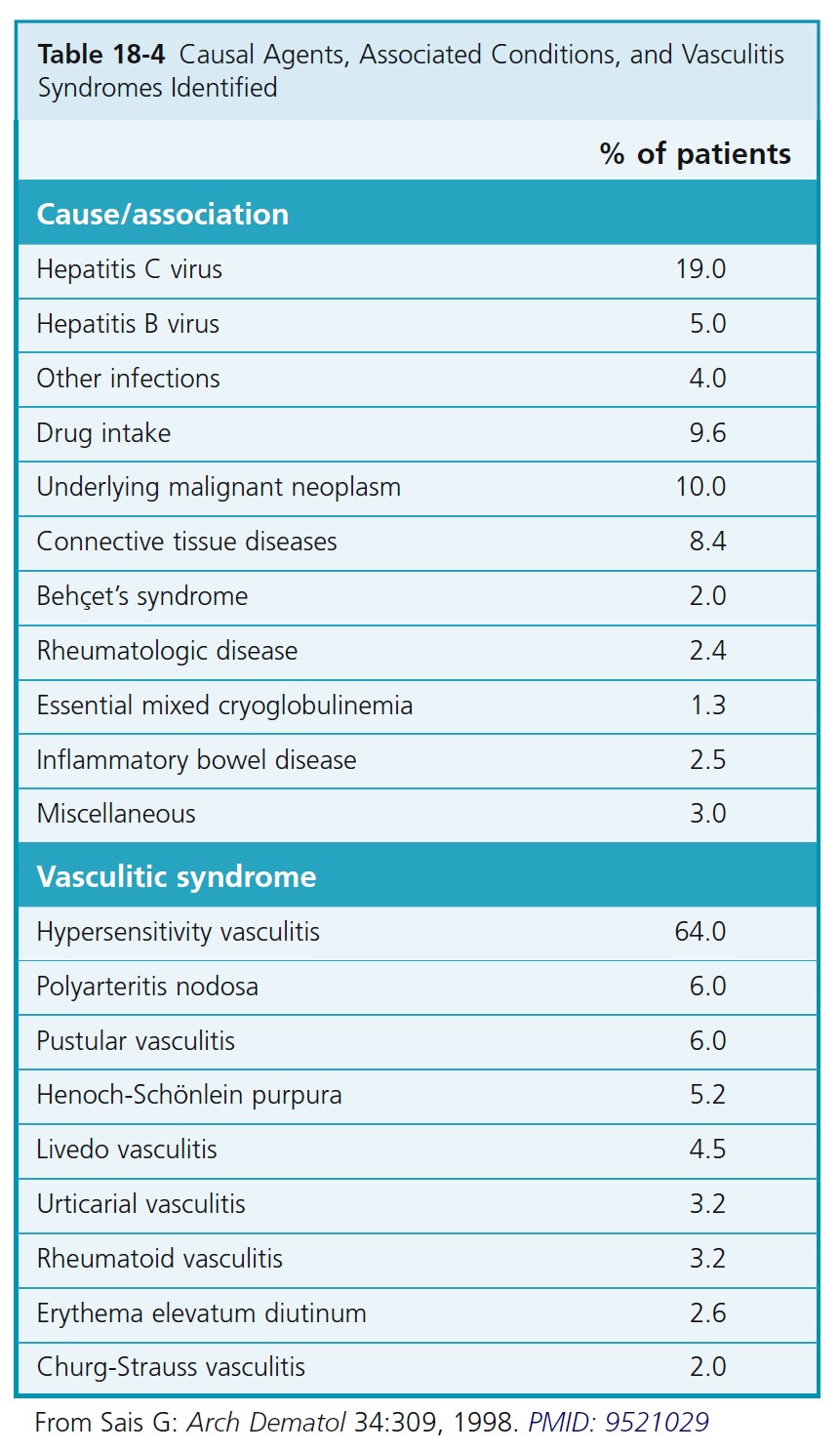

ETIOLOGY. There is hypersensitivity to various antigens (drugs, chemicals, microorganisms, and endogenous antigens) with formation of circulating immune complexes that are deposited in walls of vessels. Some of the diseases reported to be associated with hypersensitivity vasculitis and the incidence of these diseases are listed in Table 18-4 .

In many cases, the cause is not determined.

PATHOGENESIS. The vessel-bound immune complexes activate complement that is chemotactic for neutrophils. Neutrophils adhere to endothelial cells and migrate into the surrounding connective tissue. Activated endothelial cells release inflammatory mediators (cytokines) that attract inflammatory cells. There is an inflammatory response in the walls of small vessels in which leukocytes, by release of lysosomal enzymes, damage vessel walls, causing extravasation of erythrocytes. The term leukocytoclastic vasculitis describes the histologic pattern produced when leukocytes fragment (i.e., undergo leukocytoclasis during the inflammatory process, leaving nuclear debris or “dust”).

Hypersensitivity vasculitis

Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis (leukocytoclastic vasculitis, hypersensitivity vasculitis) is the most commonly seen form of small vessel necrotizing vasculitis. The disease may be limited to the skin or may involve many different organs and be coexistent with many other diseases. Histologically there is fibrinoid necrosis of small dermal blood vessels, leukocytoclasis, endothelial cell swelling, and extravasation of red blood cells (RBCs).

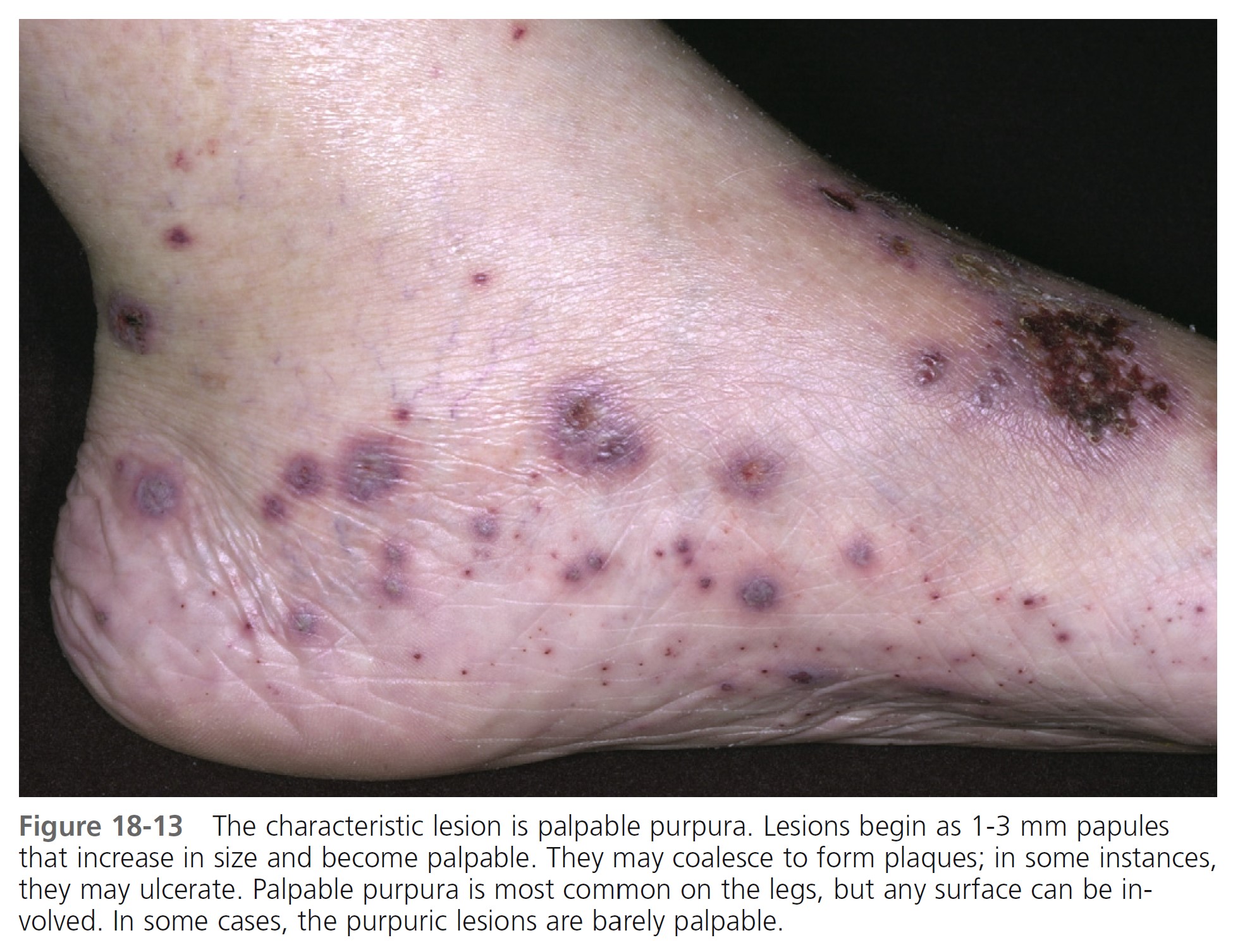

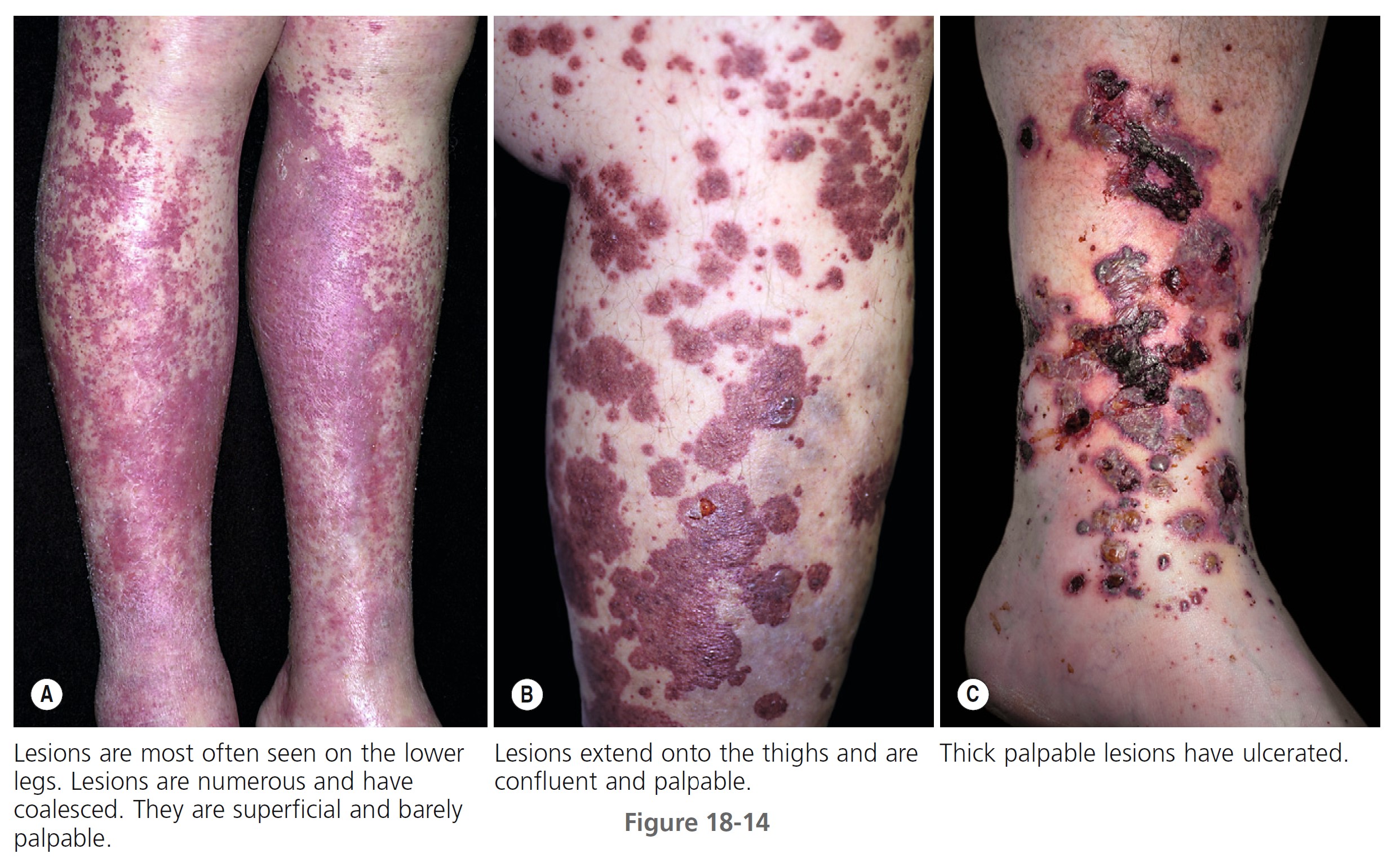

SKIN LESIONS. Prodromal symptoms include fever, malaise, myalgia, and joint pain. The characteristic lesions are referred to as palpable purpura. The lesions begin as asymptomatic, localized areas of cutaneous hemorrhage that acquire substance and become palpable as blood leaks out of damaged vessels ( Figure 18-13 ). Lesions may coalesce, producing large areas of purpura. Nodules and urticarial lesions may appear. Hemorrhagic blisters and ulcers may arise from these purpuric areas and indicate more severe vessel inflammation and necrosis. A few to numerous discrete, purpuric lesions are most commonly seen on the lower extremities but may occur on any dependent area, including the back if the patient is bedridden, or the arms. Ankle and lower leg edema may occur with lower leg lesions ( Figure 18-14 , A-C).

Small lesions itch and are painful; nodules, ulcers, and bullae may be very painful.

Lesions appear in crops, last 1 to 4 weeks, and heal with residual scarring and hyperpigmentation. Patients may experience one episode if a drug or viral infection is the cause or multiple episodes when the lesions are associated with a systemic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Recurrent crops of new lesions may appear for weeks, months, or years. The disease is usually self-limited and confined to the skin.

DURATION. In one study the disease resolved in less than 6 months in 46.9% of the patients and persisted in 43.8%. The duration of the cutaneous vasculitis ranged from 1 week to 318 months. The average duration of cutaneous lesions was 27.9 months.

SYSTEMIC DISEASE. Hypersensitivity vasculitis has many systemic manifestations; the numbers in parentheses in the following discussion indicate the approximate percentage of involvement.

An analysis of cutaneous hypersensitivity vasculitis in patients seen by two practicing dermatologists showed that the disease has a better prognosis with less systemic involvement than in those patients seen at medical center clinics. PMID: 6703752

• Kidneys (50%): Kidney disease is the most common systemic manifestation. Mild vasculitis of the kidneys causes microscopic hematuria and proteinuria. Necrotizing glomerulitis or diffuse glomerulonephritis may lead to chronic renal insufficiency and death.

• Nervous system (40%): Peripheral neuropathy with hypoesthesia or paresthesia is more common than central nervous system involvement.

• Gastrointestinal tract (36%): Vasculitis of the bowel causes abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and melena.

• Lung (30%): Pulmonary vasculitis may be asymptomatic, detected only as nodular or diffuse infiltrates on chest film; it also may be symptomatic, with cough, shortness of breath, and hemoptysis.

• Joints (30%): Symptoms vary from pain to erythema and swelling.

• Heart (50%): Myocardial angiitis produces arrhythmias and congestive heart failure.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION. Look for systemic disease with a complete history and physical examination. Examine ear, nose, and throat for signs of Wegener’s granulomatosis.

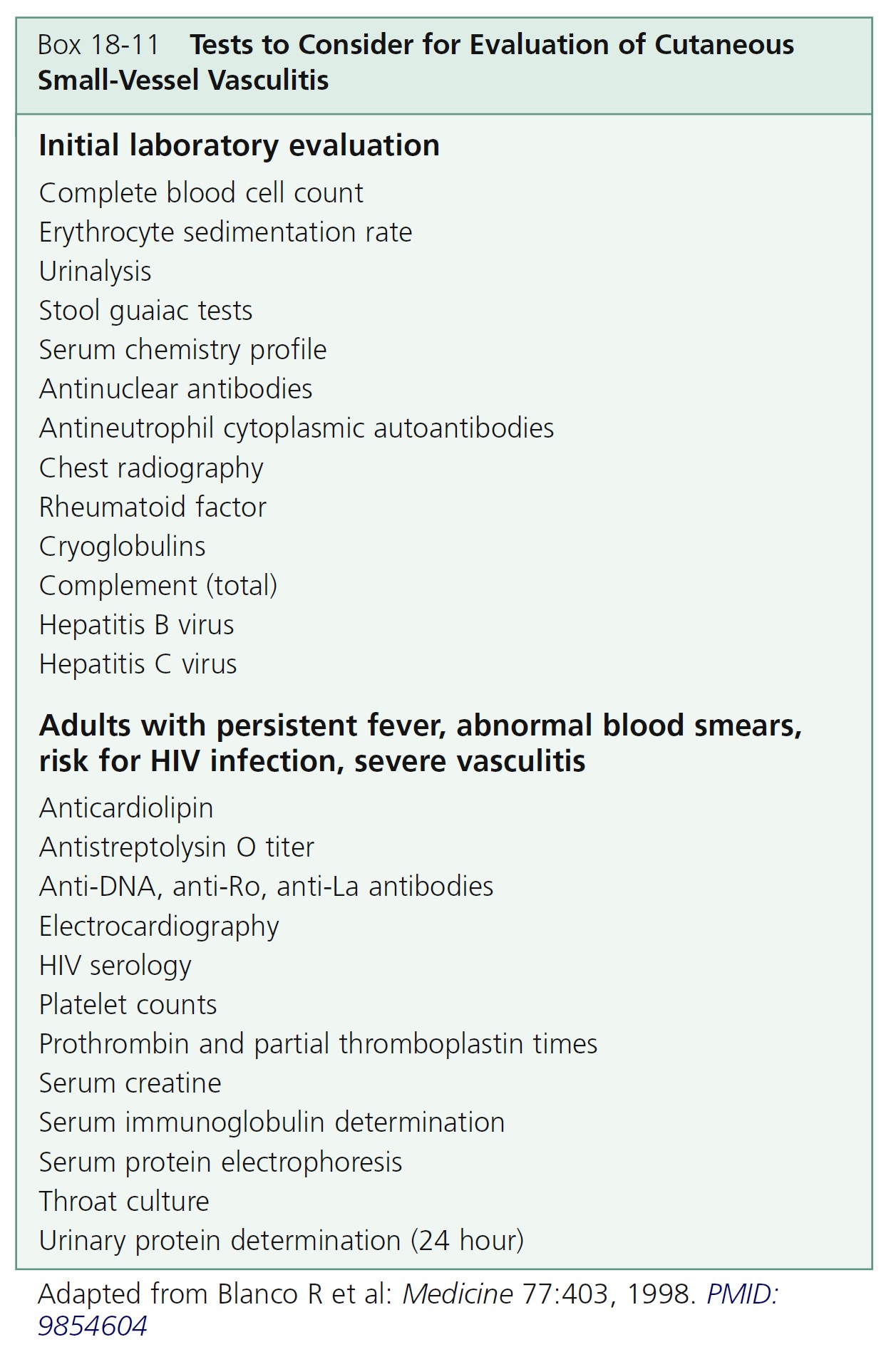

LABORATORY STUDIES. Studies to consider are listed in Box 18-11 . Decreased levels of complement components are more often present in vasculitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, cryoglobulinemia, Sjögren’s syndrome, or urticarial vasculitis. Every patient should be screened for renal involvement. Order ANCA tests when systemic vasculitis is suspected. The ESR is almost always increased during active vasculitis. A normal ESR in a patient with purpura suggests that immune complex disease is absent. Low complement levels are associated with other features such as renal disease, arthritis, and the presence of immunoreactants deposited along the basement membrane zone of the epidermis.

SKIN BIOPSY. The clinical presentation is so characteristic that a biopsy is generally not necessary. In doubtful cases, a punch biopsy should be taken from an early active lesion. The characteristic mixed infiltrate of mononuclear cells and neutrophils, fibrinoid necrosis of blood vessel walls, and nuclear dust from neutrophil fragmentation (leukocytoclasis) will be obscured if ulcerated lesions are sampled. Patients with deeper levels of vasculitis (down to the lower half of the reticular dermis) have evidence of a more severe clinical disease with systemic involvement.

IMMUNOFLUORESCENT STUDIES. Immunofluorescent studies may be done if the diagnosis cannot be determined from the clinical presentation and skin biopsy. Immune complexes are phagocytized rapidly after deposition in the vessels. Therefore the best time for biopsy of a vessel for immunofluorescence is within the first 24 hours after the lesion forms. The most common immunoreactants present in and around blood vessels are IgM, C3, and fibrin. The presence of IgA in blood vessels of a child with vasculitis suggests the diagnosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

TREATMENT. Identify and remove the offending antigen (i.e., drug, chemical, or infection). No other treatment may be necessary, and the disease may clear spontaneously. In other instances the disease persists or becomes recurrent.

Topical corticosteroids and topical antibiotic creams may be helpful. Prednisone, 60 to 80 mg per day, controls systemic symptoms and cutaneous ulceration. Taper slowly (3 to 6 weeks) to prevent rebound. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (acetylsalicylic acid, indomethacin) may be used for persistent or necrotic lesions, myalgias, fever, and arthralgia.

Colchicine, which inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis, in doses of 0.6 mg two to three times daily, might be helpful in chronic forms of the disease. Effects are seen in 7 to 10 days, and colchicine is tapered and discontinued when lesions resolve. Treatment can be continued for months if necessary, and side effects are minimal.

Dapsone 100 to 150 mg per day controlled three patients in whom disease was confined to the skin. Potassium iodide (0.3 to 1.5 gm four times daily) is useful in nodular vasculitis. H 1 antihistamines alone or with H 2 antihistamines alleviate pruritus and block histamine-induced endothelial gap formation with resultant trapping of immune complexes. Azathioprine 150 mg/day was used in patients with recalcitrant disease or steroid-induced side effects and produced a good clinical response in 4 to 8 weeks. Cyclophosphamide 2 mg/kg per day induced remissions in patients with multiple-organ involvement who were not controlled with prednisone. Methotrexate (10 to 25 mg/week) or cyclosporine (3 to 5 mg/kg per day) are alternatives for patients with a rapidly progressing course and systemic involvement. Hydroxychloroquine is not effective.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura

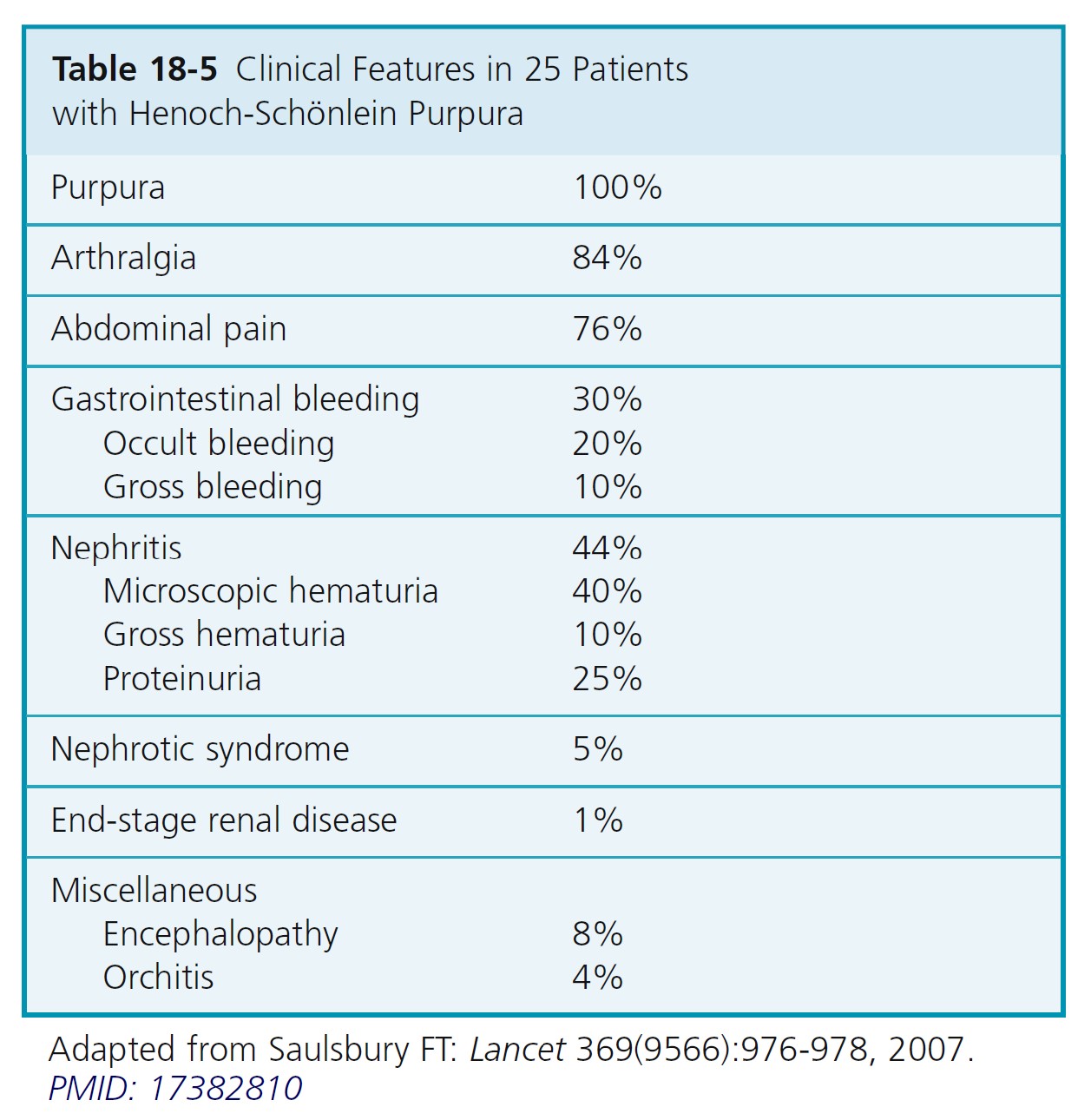

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), or anaphylactoid purpura, is an acute leukocytoclastic vasculitis that occurs mainly in children between the ages of 2 and 10, although adult cases are reported. It is the most common systemic vasculitis in children and is characterized by vascular deposition of IgA-dominant immune complexes, and preferentially involves venules, capillaries, and arterioles. Symptoms include palpable purpura over the legs and buttocks, abdominal pain (63%), GI bleeding (33%), arthralgia (82%), nephritis (40%), and hematuria ( Table 18-5 ), and, histologically, leukocytoclastic vasculitis. It is a self-limited illness, but one third of patients will have one or more recurrences of symptoms.

PROGNOSIS. HSP is usually benign and self-limiting; the degree of renal involvement determines the prognosis. The long-term prognosis is excellent for both adults and children. In 50% of cases, there are recurrences, typically in the first 3 months; these are milder and more common in patients with nephritis.

ADULTS VS. CHILDREN. The frequency of previous drug treatment, primarily antibiotics or analgesics, is similar in both groups, but previous upper respiratory tract infection is more frequent among children. No precipitating event is found in 72% of the adults and 66% of the children. Adults have a lower frequency of abdominal pain and fever and a higher frequency of joint symptoms. Adults have more frequent and severe renal involvement. An increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate is more frequent in adults. Complete recovery occurs in 93.9% of children and in 89.2% of adults. Adults required more aggressive therapy, consisting of steroids and/or cytotoxic agents. However, the final outcome of HSP is equally good in adults and children.

ETIOLOGY. HSP tends to occur in the springtime; a streptococcal or viral upper respiratory tract infection may precede the disease by 1 to 3 weeks. A cluster of cases was reported, suggesting that HSP is caused by person to person spread of an infectious agent of the respiratory tract to susceptible hosts.

A number of infectious agents and drugs have been implicated, but the etiology of HSP remains unknown.

Immunoglobulin A. IgA plays a critical role in the immunopathogenesis of HSP. There are increased serum IgA concentrations, IgA-containing circulating immune complexes, and IgA deposition in vessel walls and renal mesangium. There are two subclasses of IgA, but HSP is associated with abnormalities involving IgA1 exclusively and not IgA2. All of its features are attributable to the widespread vasculitis believed to be initiated by entrapment of circulating IgA-containing immune complexes in blood vessel walls in the skin, kidneys, and GI tract.

CLINICAL FEATURES. Prodromal symptoms include anorexia and fever. The clinical features of HSP are as follows.

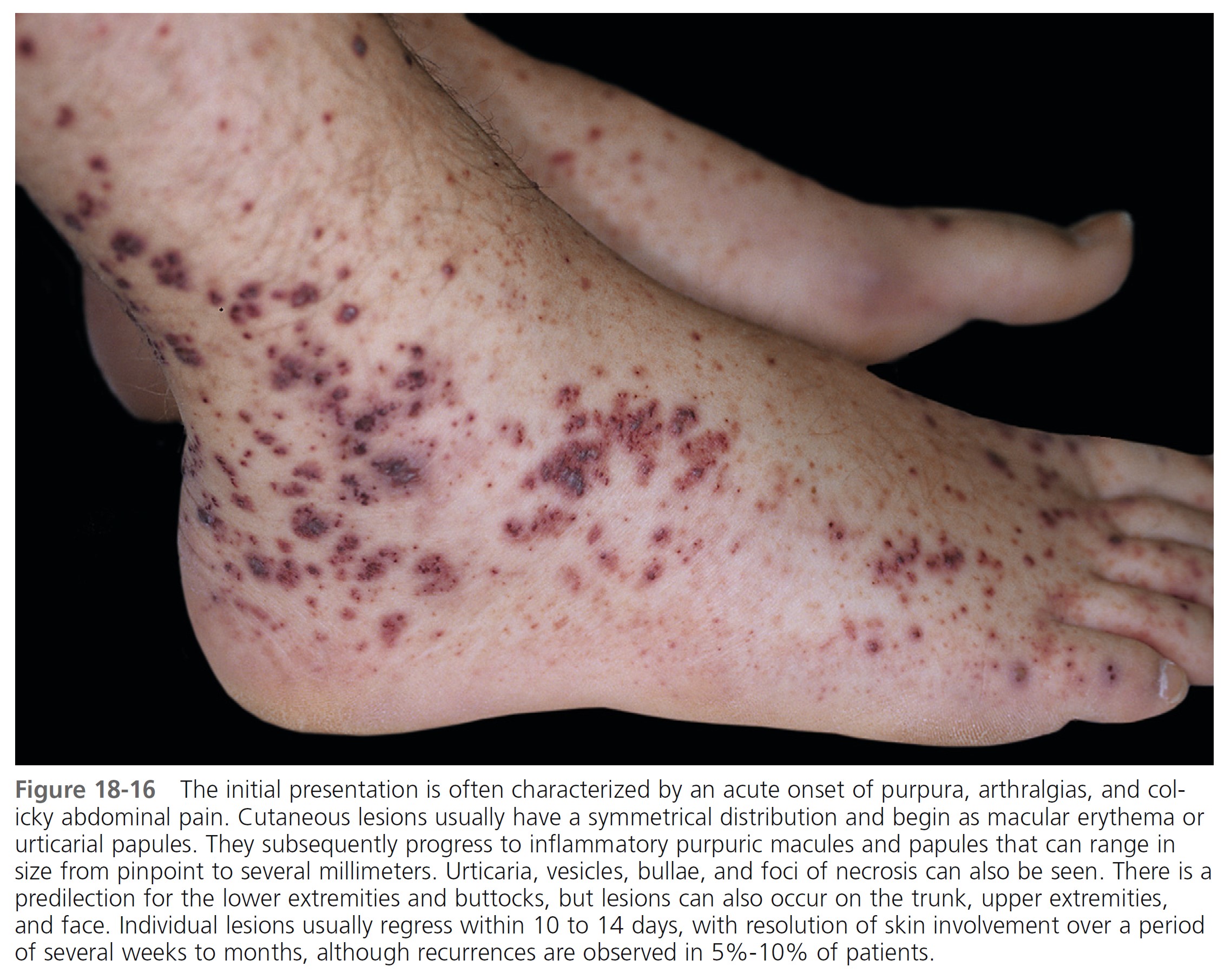

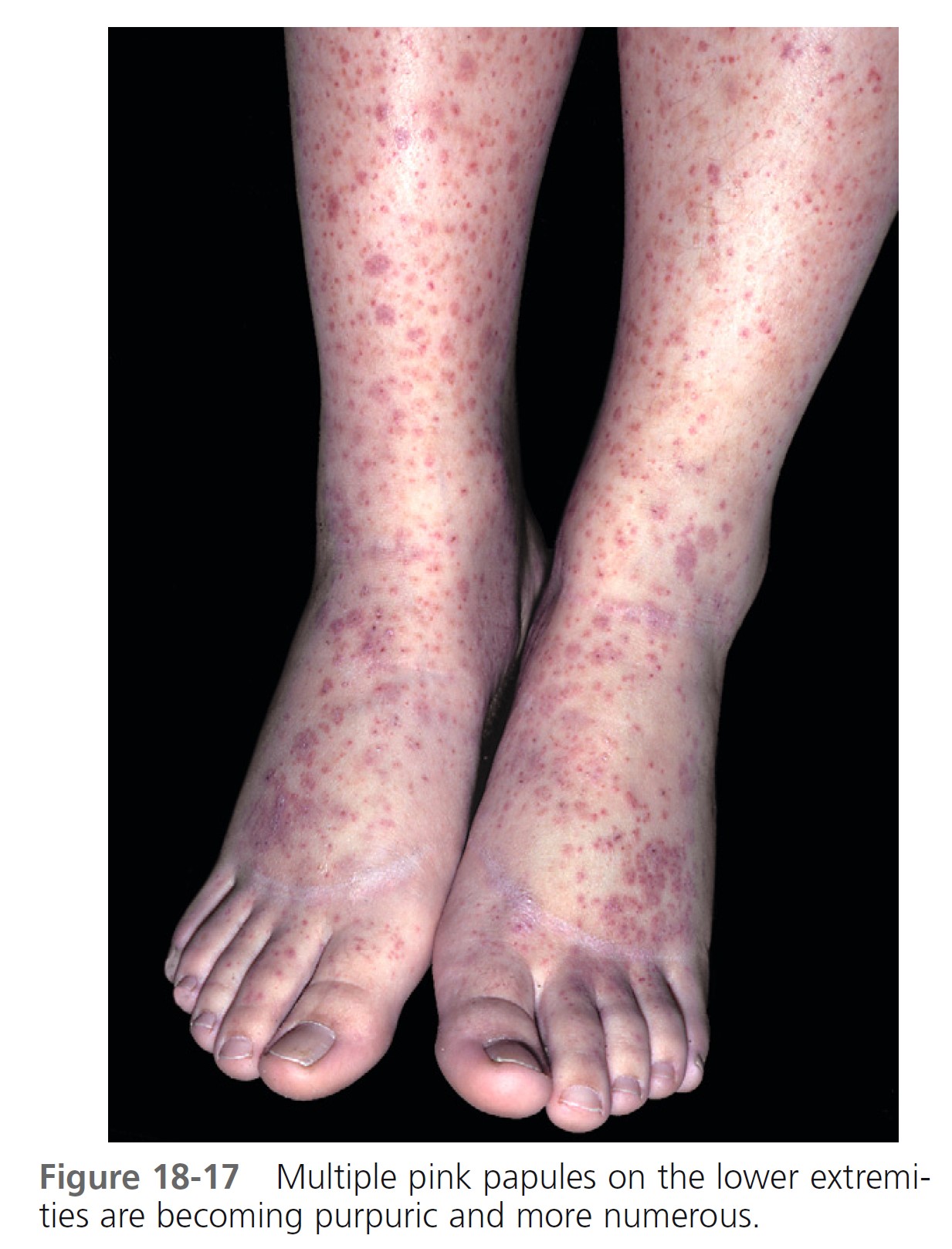

Skin. Nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura is most common on the lower extremities and buttocks but can appear on the arms, face, and ears; the trunk is usually spared ( Figures 18-15 to 18-18 ). The lesions evolve from urticarial papules into the classic leukocytoclastic vasculitic lesions within 48 hours. The lesions are 2 to 10 mm in diameter and appear in crops among coalescent ecchymoses and pinpoint petechiae. Lesions fade in several days, more rapidly with bed rest, leaving brown macules. New lesions appear with ambulation. Seventy-seven percent of patients present with cutaneous signs; 10% have no leg involvement; 4.5% have edema of the hands, feet, or face.

Abdominal symptoms. GI symptoms occur in 40% to 60% of patients; these include colicky pain, nausea, vomiting, upper GI bleeding, diarrhea, and bloody stool and are potentially the most serious manifestations. Severe abdominal pain was a significant predictor of nephritis in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Although GI bleeding occurs in 52% of patients, it is self-limiting, and blood transfusions have not been required. Symptoms precede the skin disease by up to 2 weeks and simulate a number of inflammatory or surgically treated bowel diseases. Major complications of abdominal involvement develop in 4.6%, of which intussusception is by far the most common. The intussusceptum is confined to the small bowel in 58% and it is frequently inaccessible to demonstration by contrast enema.

Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice. It provides an easy, noninvasive, objective method of monitoring patient progress. It allows direct visualization of bowel involvement and detection of complications such as intussusception. It also demonstrates edematous hemorrhagic infiltration of the intestinal wall, which can occur in the duodenal, jejunal, and ileal segments. Ultrasonography complements serial clinical assessment, clarifies the nature of the gastrointestinal involvement, and reduces the likelihood of unnecessary surgery.

Routine abdominal radiographs are not recommended, unless perforation is clinically suspected.

Upper GI endoscopy can be useful. Inflammation of the duodenum, especially of the second part, is characteristic of HSP. Upper GI endoscopy shows redness, swelling, petechiae or hemorrhage, or erosions and ulceration of the mucosa. Histology of mucosal biopsy specimens shows nonspecific inflammation with positive staining for IgA in the capillaries.

Joint symptoms. Arthralgia, probably resulting from painful periarticular edema rather than from inflammatory joint disease, involves the ankles, knees, and dorsum of the hands and feet in more than 80% of patients. It is often incapacitating, but it is self-limiting and nondeforming.

Nephritis. The long-term prognosis of HSP is directly dependent on the severity of renal involvement. Nephritis occurs in 20% to 50% of children. The renal disease is usually milder in children and almost always heals. The onset may be acute or delayed. Acute nephritis occurs from 1 to 12 days after the onset of other signs and symptoms. The onset of renal involvement may be delayed for weeks or months in a substantial proportion of patients. Microscopic hematuria is a constant feature, but episodes of gross hematuria occur in 40% of patients with nephritis. Proteinuria and hematuria are found in about 40% of cases. Urinary abnormalities can persist for 2 to 5 years in patients who develop nephritis in the acute phase of HSP. Progression to nephrotic syndrome and acute and chronic renal failure is possible.

When HSP presents with more than just microhematuria, only 72% of cases proceed to complete recovery. Heavy proteinuria at onset, focal sclerotic and tubulointerstitial changes, and crescents and capsular adhesions are poor prognostic indicators. After a follow-up of at least 8 years, 53% of patients are clinically in remission. Evidence of renal disease may reappear after apparent complete recovery. Childhood HS nephritis requires long-term follow-up, especially during pregnancy. A study of 78 subjects who had HS nephritis during childhood (at a mean of 23.4 years after onset) showed that severity of clinical presentation and initial findings on renal biopsy correlate well with outcome but have poor predictive value in individuals. Forty-four percent of patients who had nephritic or nephrotic syndromes at onset have hypertension or impaired renal function; 82% of those who presented with hematuria (with or without proteinuria) are normal. Of 44 full-term pregnancies, 16 were complicated by proteinuria and/or hypertension, even in the absence of active renal disease.

The renal pathologic findings present a spectrum from mild focal glomerulitis to necrotizing or proliferative glomerulonephritis with diffuse mesangial proliferation. Diffuse mesangial deposits of IgA are seen on immunofluorescent studies. HS nephritis may be the single most common form of crescentic glomerulonephritis, accounting for 30% of cases.

Adults. A multicenter collaborative study of 152 patients compared the progression of renal disease in children and adults with HPS nephritis. Crescents were found in 36% of adults and 34.6% of children, nephrotic-range proteinuria in 29.5% of adults and 28.1% of children, and functional impairment in 24.1% of adults and 36.9% of children. The outcome was similar for both age groups (remission, 32.5% of adults and 31.6% of children; renal function impairment, 31.6% of adults and 24.5% of children). End-stage renal disease was observed in 15.8% of adults and in 7% of children. None of the children died, and adult survival was 97% at 5 years. In adults at presentation, renal function impairment and also proteinuria greater than 1.5 gm per day and hypertension were negative prognostic factors. In children no definite level of proteinuria, hypertension, or other data were found to be associated with poor prognosis. PMID: 9394311

A recent infectious history, pyrexia, the spread of purpura to the trunk, and biologic markers of inflammation are predictive factors for renal involvement.

Acute scrotal swelling. Acute scrotal swelling may be the presenting manifestation and occur in up to 15% of boys with HSP. The vasculitis of HSP may involve the scrotum and clinically mimic diseases requiring surgical intervention, such as testicular torsion or an incarcerated inguinal hernia. Sonographic findings include an enlarged, rounded epididymis, thickened scrotal skin, and a hydrocele with intact vascular flow in the testicles. Nuclear imaging may be used to assess testicular perfusion. The sonographic findings in the scrotum are sufficiently characteristic to allow distinction from torsion in most cases. These findings help prevent unnecessary surgical exploration.

PATHOLOGY. The pathology of HSP is that of an acute vasculitis of arterioles and venules in the superficial dermis and the bowel. Immunofluorescence staining of tissues usually shows the presence of IgA in the walls of the arterioles and in the renal glomeruli. The serum IgA level is frequently higher than normal.

DIAGNOSIS. There are no diagnostic laboratory tests. Complete blood counts (CBCs), antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), platelet counts, and coagulation studies are normal. The ESR may be elevated, and the serum complement level may be depressed. In one study, serum IgA concentrations were increased in 44% of children. Direct immunofluorescent studies show IgA deposition in blood vessels (75% in affected skin and 67% in uninvolved skin) of the superficial dermis. IgA1 is the dominant IgA subclass.

IgA in vessel walls is a sensitive and specific marker that helps to solidify the diagnosis of HSP. This finding should not be used as the sole criterion for making the diagnosis because it is seen in many other disorders, such as venous stasis and erythema nodosum. One study disclosed a significant correlation between plasma levels of anaphylatoxins C3a and C4a and plasma creatine levels in patients with nephritis. The role of IgA ANCA has not been defined.

MANAGEMENT. The offending antigen must be identified and removed. The possibilities include infections, malignancies, foods, and drugs. Patients with ANCA associated small vessel vasculitis who present with purpura, abdominal pain, and nephritis but do not have IgA immune deposits do not have Henoch-Schönlein purpura and do not have a good prognosis; they should be treated quickly with immunosuppressive therapy.

Corticosteroids. The joint pain, inflammation, and painful cutaneous edema are treated with analgesics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents, and corticosteroids. Corticosteroid therapy may hasten the resolution of arthritis and abdominal pain but does not prevent recurrences. Corticosteroids in usual doses have no effect on established nephritis. The optimal management of HSP associated gastrointestinal and renal involvement has not yet been determined. Reports favor a short course of oral corticosteroids for severe abdominal pain and immunosuppressive therapy for patients with progressive nephritis. Prednisone in a dose of 1 mg/kg a day for 2 weeks, then tapered over 2 weeks, decreased the intensity and duration of gastrointestinal symptoms and the severity of joint symptoms. PMID: 16887443

That study also showed that prednisone hastened the resolution of mild HSP nephritis. The use of corticosteroids early in the course of HSP does not seem to be effective in preventing the development of nephritis, however. Thus corticosteroid therapy is beneficial in ameliorating the gastrointestinal and joint symptoms and perhaps in shortening the duration of mild nephritis, but not in preventing delayed nephritis. There is no evidence that corticosteroid therapy is effective in treating the purpura, shortening the duration of the disease, or preventing recurrences.

Intravenous pulse methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg a day for 3 consecutive days) followed by oral corticosteroids was effective in reversing severe nephritis and preventing progression. Others have reported the benefits of corticosteroids combined with cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, or cyclosporine in severe HSP nephritis and thus early aggressive therapy is warranted in patients with severe nephritis. PMID: 17382810

NEUTROPHILIC DERMATOSES

Neutrophilic dermatosis represents a continuous spectrum encompassing five entities: subcorneal pustular dermatosis, Sweet’s syndrome, erythema elevatum diutinum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. The different neutrophilic dermatoses are manifestations of a potentially multisystemic neutrophilic disease. All may present with pustules, plaques, nodules, and ulcerations. Histologically, a neutrophilic infiltrate appears at variable levels in the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Systemic manifestations include generalized symptoms and joint, renal, ocular, and lung involvement. There is an overlap in the clinical manifestations of the four entities. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis and neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis are very rare and not described here.

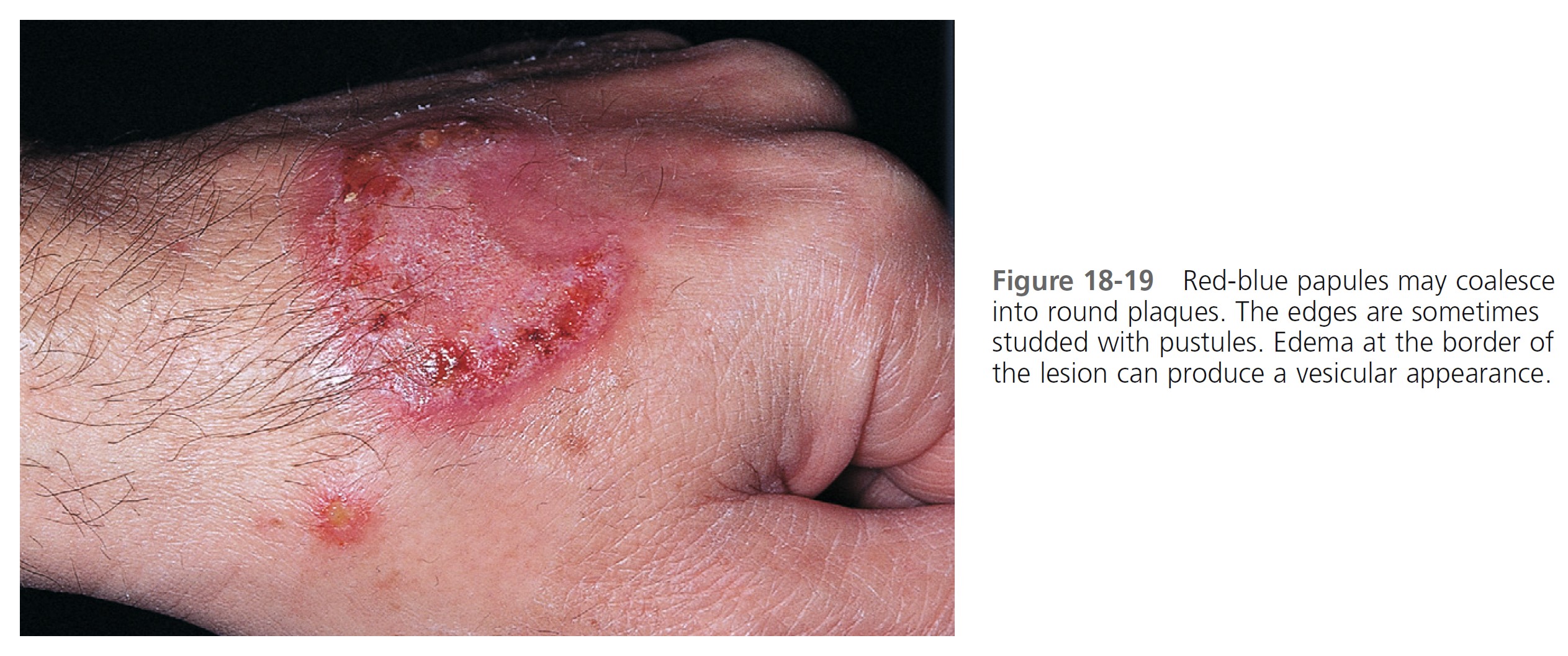

Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis)

Sweet, in 1964, described a disease with four features: fever; leukocytosis; acute, tender, red plaques; and a papillary dermal infiltrate of neutrophils. This led to the name acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Larger series of patients showed that fever and neutrophilia are not consistently present. The diagnosis is based on the two constant features—a typical eruption and the characteristic histologic features; thus the eponym Sweet’s syndrome (SS) is used. The criteria of the diagnosis of SS are listed in Box 18-12 .

Eighty-six percent of patients are women with a preceding upper respiratory tract infection. The mean age at presentation is 56 years (range, 22 to 82 years). SS is common in Japan. A genetic predisposition is possible; HLA-Bw54 was found to be a risk factor in a series of Japanese patients with SS.

ETIOLOGY. Sweet’s syndrome can be classified based upon the clinical setting in which it occurs: classical or idiopathic Sweet’s syndrome, malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome, and drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome.

SYSTEMIC DISEASES. SS is a reactive phenomenon and should be considered a cutaneous marker of systemic disease. Careful systemic evaluation is indicated, especially when cutaneous lesions are severe or hematologic values are abnormal. Approximately 20% of cases are associated with malignancy, predominantly hematologic, especially acute myelogenous leukemia. An underlying condition (streptococcal infection, inflammatory bowel disease, nonlymphocytic leukemia and other hematologic malignancies, solid tumors, pregnancy) is found in up to 50% of cases. Attacks of SS may precede the hematologic diagnosis by 3 months to 6 years, so that close evaluation of patients in the “idiopathic” group is required.

There is now good evidence that treatment with hematopoietic growth factors, including granulocyte colony–stimulating factor (G-CSF), which is used to treat acute myelogenous leukemia, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, can cause Sweet’s syndrome. Lesions typically occur when the patient has leukocytosis and neutrophilia but not when the patient is neutropenic.

However, G-CSF may cause SS in neutropenic patients because of the induction of stem cell proliferation, the differentiation of neutrophils, and the prolongation of neutrophil survival.

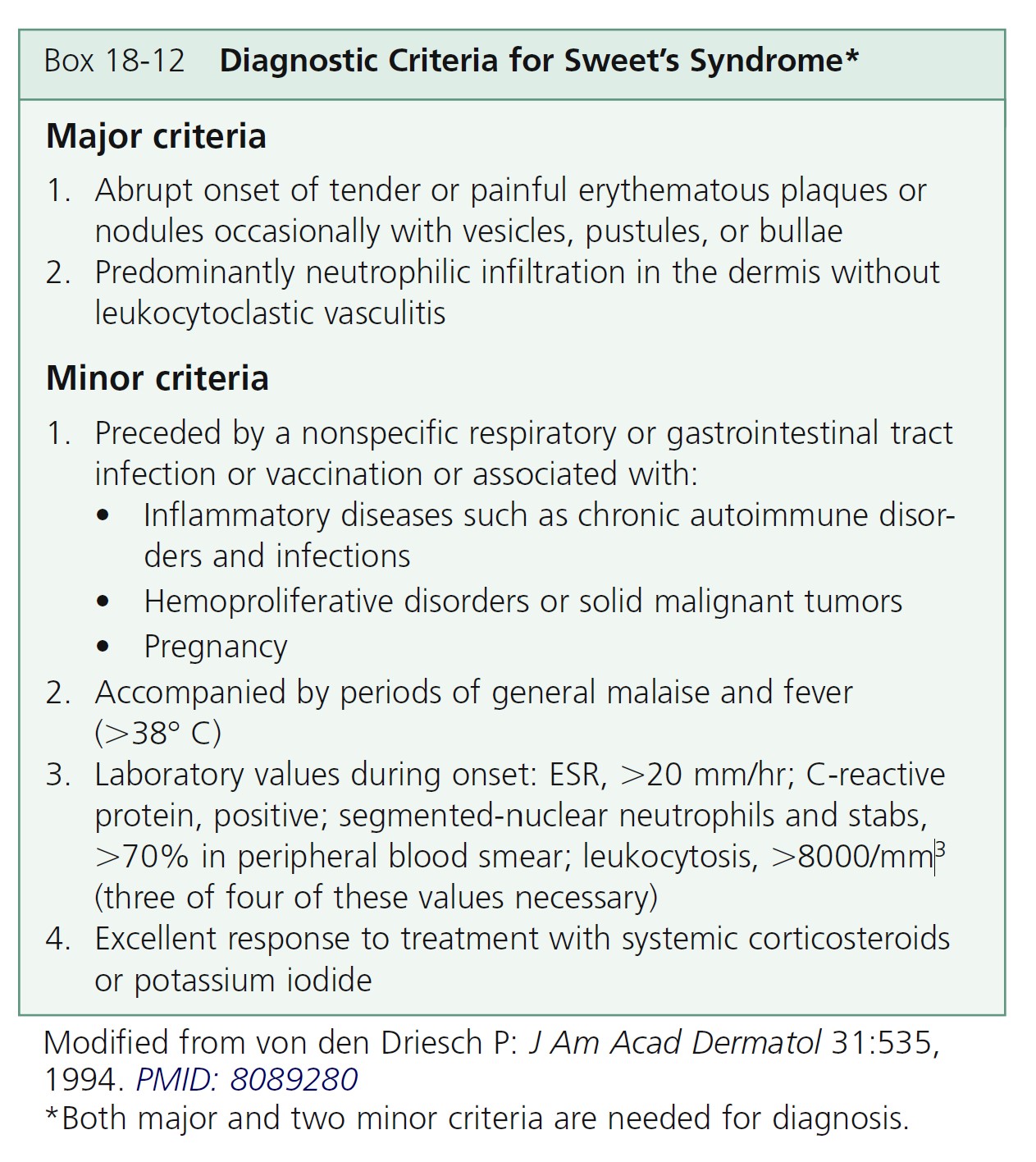

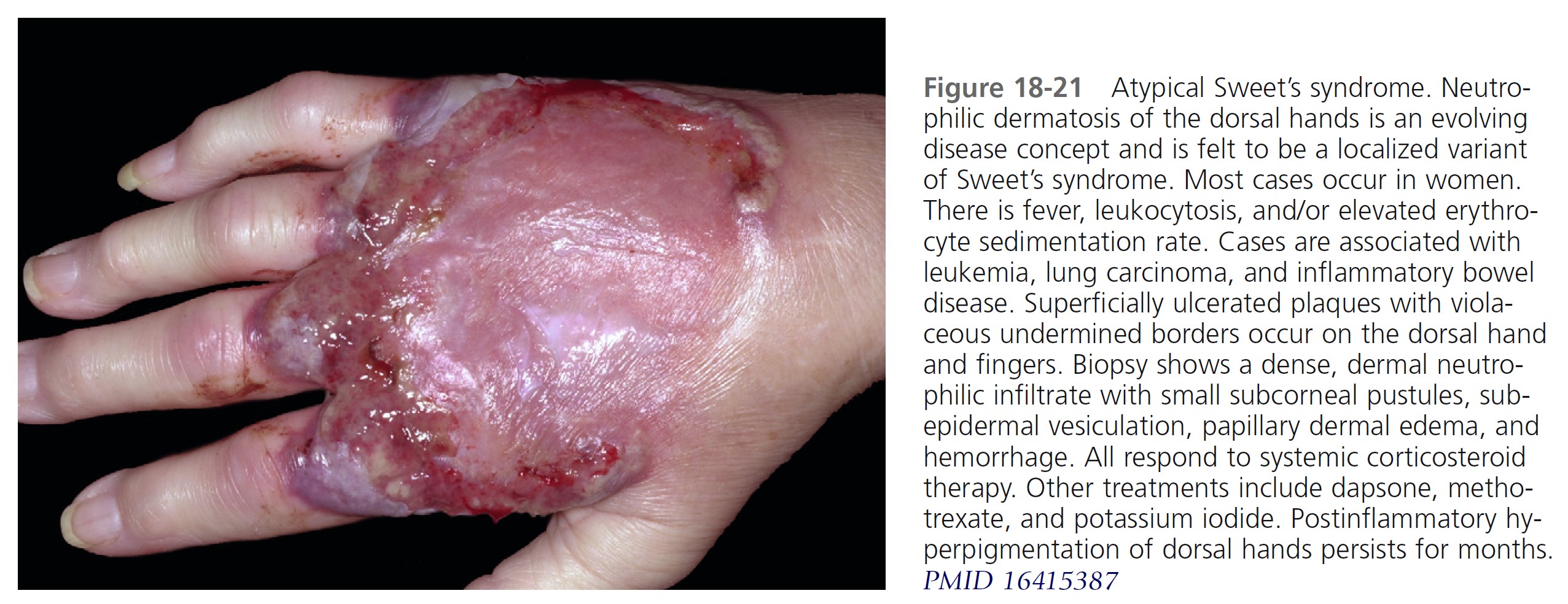

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS. Acute, tender, erythematous plaques; nodes; pseudovesicles; and, occasionally, blisters with an annular or arciform pattern occur on the head, neck, legs, and arms, particularly the back of the hands and fingers ( Figures 18-19 to 18-22 ). The trunk is rarely involved. Fever (50%); arthralgia or arthritis (62%); eye involvement, most frequently conjunctivitis or iridocyclitis (38%); and oral aphthae (13%) are associated features. Differential diagnosis includes erythema multiforme, erythema nodosum, adverse drug reaction, and urticaria. Recurrences are common and affect up to one third of patients.

LABORATORY STUDIES. Studies show a moderate neutrophilia (less than 50%), elevated ESR (greater than 30 mm/hr) (90%), and a slight increase in alkaline phosphatase level (83%). Skin biopsy shows a papillary and mid-dermal mixed infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with nuclear fragmentation and histiocytic cells. The infiltrate is predominantly perivascular with endothelial cell swelling in some vessels, but vasculitic changes (thrombosis; deposition of fibrin, complement, or immunoglobulins within the vessel walls; red blood cell extravasation; inflammatory infiltration of vascular walls) are absent in early lesions.

Vasculitis occurs secondary to noxious products released from neutrophils. Blood vessels in lesions of longer duration are more likely to develop vasculitis than those of shorter duration because of prolonged exposure to noxious metabolites. Therefore vasculitis does not exclude a diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome.

TREATMENT. Systemic corticosteroids (prednisone 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg of body weight per day) produce rapid improvement and are the “gold standard” for treatment. The patient’s temperature, WBC count, and eruption improve within 72 hours. The skin lesions clear within 3 to 9 days. Abnormal laboratory values rapidly return to normal. There are, however, frequent recurrences. Corticosteroids are discontinued by tapering over 2 to 6 weeks. Resolution of the eruption is occasionally followed by milia and scarring. The disease clears spontaneously in some patients. Topical and/or intralesional corticosteroids may be effective as either monotherapy or adjuvant therapy.

Oral potassium iodide or colchicine may induce rapid resolution. Patients who have a potential systemic infection or in whom corticosteroids are contraindicated can use these agents as a first-line therapy.

In one study, indomethacin 150 mg per day was given for the first week followed by indomethacin 100 mg per day for 2 additional weeks. Of the 18 patients, 17 had a good initial response; fever and arthralgias were markedly attenuated within 48 hours, and eruptions cleared between 7 and 14 days. Patients whose cutaneous lesions continued to develop were successfully treated with prednisone (1 mg/kg per day). No patient had a relapse after discontinuation of indomethacin. PMID: 9091476

Other alternatives to corticosteroid treatment include dapsone, doxycycline, clofazimine, and cyclosporine. All of these drugs influence migration and other functions of neutrophils.

Erythema elevatum diutinum

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare skin disease (average age, 53 years; range, 32 to 65 years). There are persistent, nonpurpuric, deep, brown-red to purple papules, nodules, and plaques. Blisters and ulcers can develop. Lesions are symmetrically distributed on extensor surfaces on the extremities with a preference for joint regions. Occasionally lesions are found on the buttocks, face, and torso. EED may be a complication of HIV infection. Cutaneous lesions may closely resemble Kaposi’s sarcoma and other malignant neoplasms. The lesions are often accompanied by arthralgias (in approximately 40% of patients) and drug intolerance.

ETIOLOGY. EED is most likely caused by immune complex deposition (Arthus reaction) in the dermal vessels. Excess exposure to antigens (recurrent infections) or situations in which high levels of antibody occur (e.g., paraproteinemias) are likely to result in immune complexes. The cause of this disorder might be an allergic reaction to streptococcal superantigens. Associated medical problems include hypergammaglobulinemia, both monoclonal (IgA clonal gammopathies) and polyclonal; multiple myeloma; and myelodysplasia. EED may precede the myeloproliferative disorders by up to 7.8 years. Chronic infection or recurrent infections (both streptococcal and non-streptococcal) are also reported.

HISTOLOGY. Early lesions show leukocytoclastic vasculitis and a massive dermal infiltrate composed mainly of neutrophils, histiocytes/macrophages, and Langerhans cells. Later lesions contain patterned (storiform or concentric) fibrosis and a dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes/macrophages and Langerhans cells. Lipid material forms in some older lesions. The term extracellular cholesterosis is used to describe this process.

LABORATORY STUDIES. Laboratory studies to consider for patients with EED include skin biopsy, serum protein electrophoresis, quantitative immunoglobulins, immunoelectrophoresis, cryoglobulins, and complement studies (C3, C4, and CH50). Direct immunofluorescence studies are generally nondiagnostic.

TREATMENT. Dapsone (e.g., 100 mg per day) is the treatment of choice. One case of EED that was unresponsive to dapsone was successfully treated with colchicine.

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare, poorly understood, noninfectious neutrophilic ulcerating skin disease. It often occurs in patients with chronic underlying inflammatory or malignant disease such as ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic active hepatitis, Crohn’s disease, IgA monoclonal gammopathy, and hematologic and lymphoreticular malignancies, but in 40% to 50% of patients, no associated disease is found. Trauma (pathergy) may precede PG in a few patients. The disease is recurrent in approximately 30% of patients. In rare instances, PG occurs in children; thus it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pustular disorders in children with underlying conditions such as ulcerative colitis. A seronegative arthritis affecting large joints is present in approximately 40% of cases.

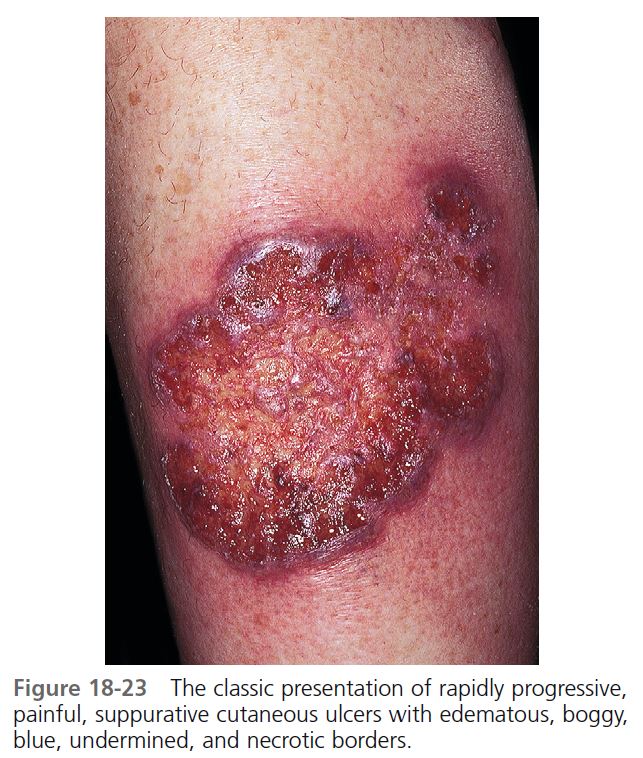

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS. Lesions are most commonly found on the lower legs, but they may occur on the thighs, buttocks, chest, head, neck, and anywhere on the skin. One study showed that lesions were multiple in 71% of cases, and more than 50% were situated below the knees. The lesion begins as a tender, red macule or papule, pustule, nodule, or bulla. Pustules or vesicles appear on the surface, and the surrounding skin becomes dusky red and indurated. A necrotizing inflammatory process extends peripherally from the primary lesion, resulting in a necrotic ulcer or ulcers with a purulent base with an undetermined purple-to-red margin and a halo of surrounding erythema ( Figures 18-23 to 18-26 ). The fully evolved lesion is generally less than 10 cm, but it may be enormous. The lesions tend to endure, lasting months to years, and heal with cribriform scarring.

BOWEL DISEASE. PG occurs both in ulcerative colitis and in Crohn’s disease. Approximately 50% of PG cases occur in association with ulcerative colitis. Approximately 2% of patients with active and extensive ulcerative colitis have PG, and another 4% of patients with active ulcerative colitis have erythema nodosum, which in its early stages can be confused with PG. Males and females are affected equally. The mean duration of chronic ulcerative colitis before the appearance of erythema nodosum and PG is 5 and 10 years, respectively. The lesions generally appear during the course of active bowel disease, but they also occur in inactive colitis or less severe disease and may not appear until after colectomy. Pyoderma resolved without intestinal resection in two thirds of patients. Healing after intestinal resection is unpredictable regarding both timing and extent of resection.

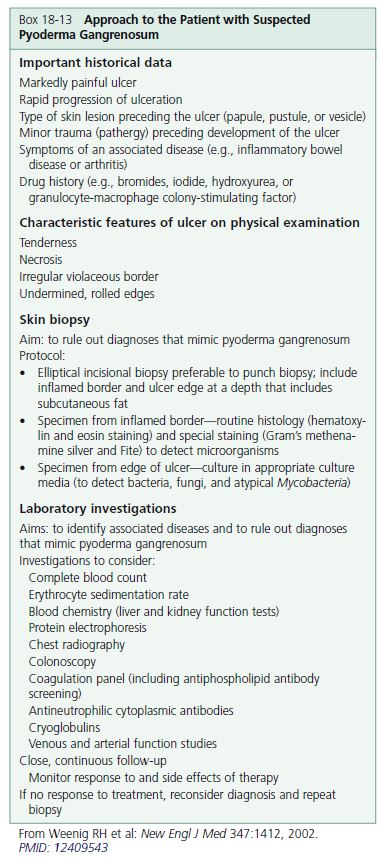

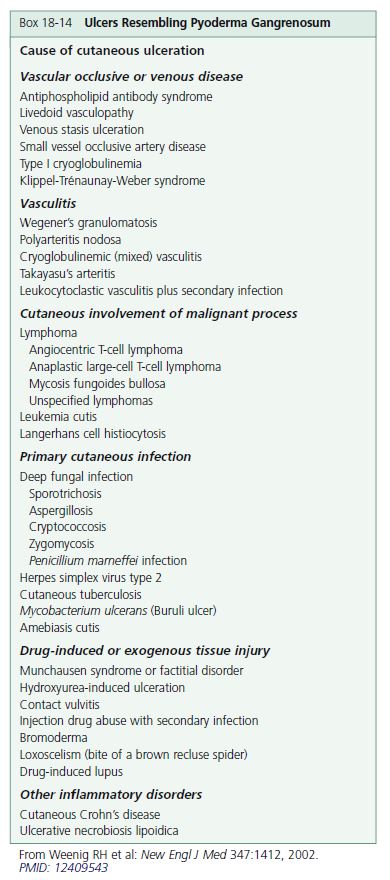

DIAGNOSIS. The diagnosis is based on clinical and pathologic features and requires exclusion of conditions that produce ulcerations ( Boxes 18-13 and 18-14 ). The diagnosis is difficult to make because of the condition’s ability to mimic other ulcerative lesions and its lack of specific laboratory and pathologic findings. Histopathologically, PG evolves from folliculitis and abscess formation; it may also show leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The lesions then evolve to suppurative granulomatous dermatitis and finally regress with prominent fibroplasia. These changes are nonspecific; therefore biopsy is of little diagnostic value. No specific abnormal laboratory determination has been found that is useful to diagnosis. Serum protein immunoelectrophoresis may be ordered to test for monoclonal gammopathy.

TREATMENT. Systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine are common treatments for extensive disease. Prednisolone (60 to 120 mg) is started at high doses. Combinations of corticosteroids with cytotoxic drugs such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or chlorambucil are used in patients with disease that is resistant to corticosteroids. Many other treatments are reported. Trauma must be avoided.

APPROACH TO RAPIDLY ADVANCING DISEASE. Rapidly advancing disease is treated with oral corticosteroids. If response is slow then consider using infliximab IV. An induction dose of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6 is followed by further treatments as necessary. Another immunosuppressant, such as azathioprine, is given at the same time as infliximab. PMID: 16858047

Oral immunosuppressive agents. Immunosppressive agents may be the most effective treatment. When corticosteroids fail, the most widely used alternative is cyclosporine. Improvement is seen within 3 weeks with a dose of 3 to 5 mg/kg/day. An intravenous bolus of cyclophosphamide is reported to be effective in inducing a remission. Oral chlorambucil 2 to 4 mg/day in combination with prednisone or used alone is an effective corticosteroidsparing agent. Mycophenolate mofetil (2 gm/day) or tacrolimus (0.1 mg/kg/day) may be effective.

Anti-tumor necrosis factor agents. Pyoderma is reported to respond to infliximab and etanercept. There is more experience with infliximab.

Localized steroids. The small early lesion may be aborted with an intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog 10 mg/ml or 40 mg/ml). Group II to V topical steroids with or without occlusion may be effective.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% or pimecrolimus cream 1% may be effective for mild or early cutaneous lesions.

SCHAMBERG’S DISEASE

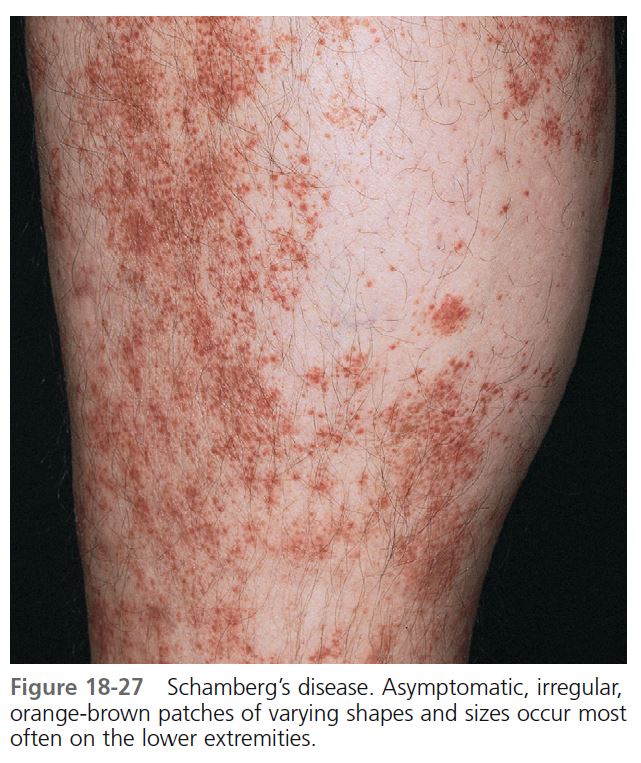

Schamberg’s disease (progressive pigmented purpuric dermatosis, purpura simplex) is an uncommon eruption characterized by petechiae and patches of brownish pigmentation (hemosiderin deposits), particularly on the lower extremities. Patients are frightened by this vasculitic appearing eruption, but there is no hematologic disease, venous insufficiency, or associated internal disease. Males are affected more often than females. Children are also affected. Lesions remain for months or years and present only a cosmetic problem. Histologically, there is inflammation and hemorrhage without fibrinoid necrosis of vessels. The cause is unknown, but a cellular immune reaction may play a role. In some patients, the eruption was related to medications.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS. Asymptomatic, irregular, orange-brown patches of varying shapes and sizes appear ( Figure 18-27 ). The most characteristic feature is orange-brown, pinhead-sized “cayenne pepper” spots. Mild erythema and scaling sometimes cause slight itching. Lesions are most common on the lower legs, but they can appear on the upper body. New spots can appear and older ones can fade. In contrast to hypersensitivity vasculitis (palpable purpura), the lesions are macular.

MANAGEMENT. The patient should be assured that there is no systemic disease. Inform patients that the pigmentation lasts for years. Mild itching and erythema respond quickly to group V topical steroids. Lesions persist, but 67% eventually clear.