Urticaria, also referred to as hives or wheals, is a common and distinctive reaction pattern. Hives may occur at any age; up to 20% of the population will have at least one episode. Hives may be more common in atopic patients. Urticaria is classified as acute or chronic . The majority of cases are acute, lasting from hours to a few weeks. Angioedema frequently occurs with acute urticaria, which is more common in children and young adults. Chronic urticaria (arbitrarily defined as episodes of urticaria lasting more than 6 weeks) is more common in middle-aged women.

Because most individuals can diagnose urticaria and realize that it is a self-limited condition, they do not seek medical attention.

The cause of acute urticaria is determined in many cases, but the cause of chronic urticaria is determined in only 5% to 20% of cases. Patients with chronic urticaria present a frustrating problem in diagnosis and management. History taking is crucial but tedious, and treatment is usually supportive rather than curative.

These patients are often subjected to detailed and expensive medical evaluations that usually prove unrewarding. Studies demonstrate the value of a complete history and physical examination followed by the judicious use of laboratory studies in evaluating the results of the history and physical examination.

CLINICAL ASPECTS

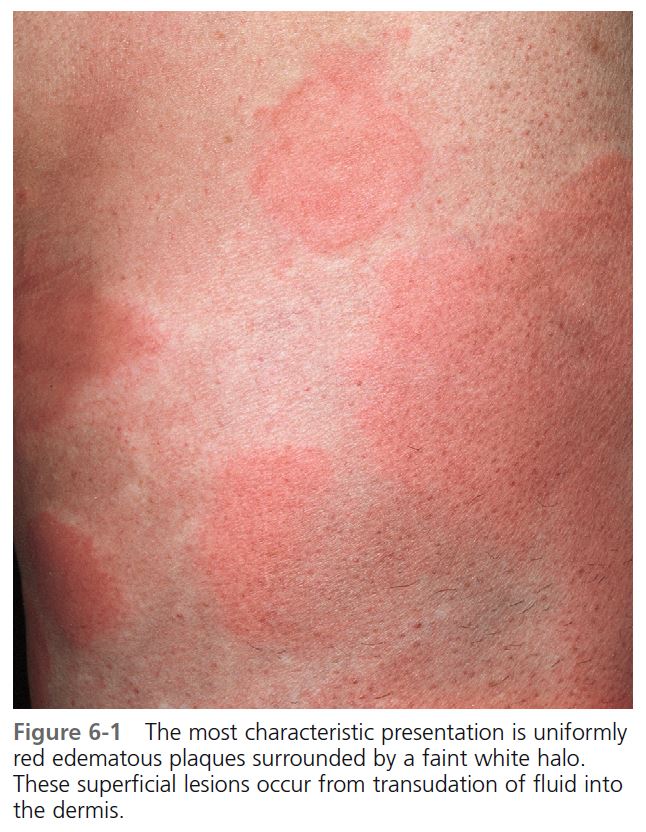

DEFINITION. A hive or wheal is a circumscribed, erythematous or white, nonpitting, edematous, usually pruritic plaque that changes in size and shape by peripheral extension or regression during the few hours or days that the individual lesion exists. The edematous, central area (wheal) can be pale in comparison to the erythematous surrounding area (flare).

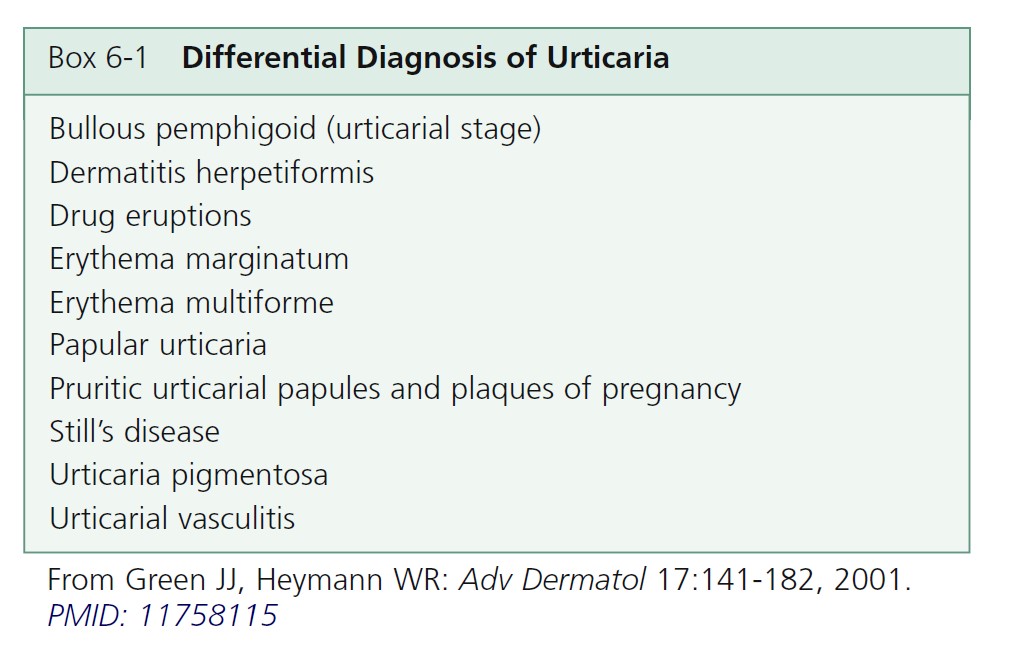

The evolution of urticaria is a dynamic process. New lesions evolve as old ones resolve. Hives result from localized capillary vasodilation, followed by transudation of protein-rich fluid into the surrounding tissue; they resolve when the fluid is slowly reabsorbed. The edema in urticaria is found in the superficial dermis. Lesions of angioedema are less well demarcated. The edema in angioedema is found in the deep dermis or subcutaneous/submucosal locations. The differential diagnosis of hives is found in Box 6-1 .

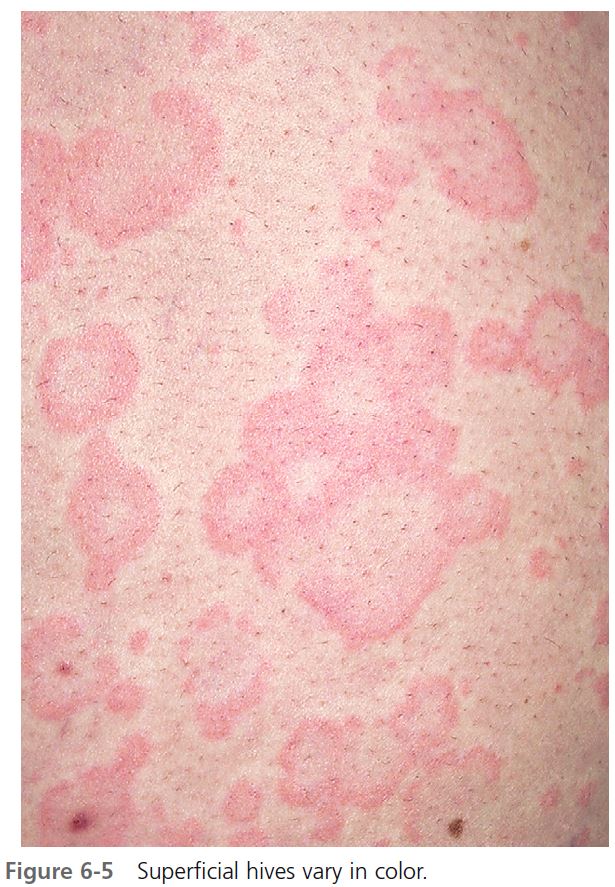

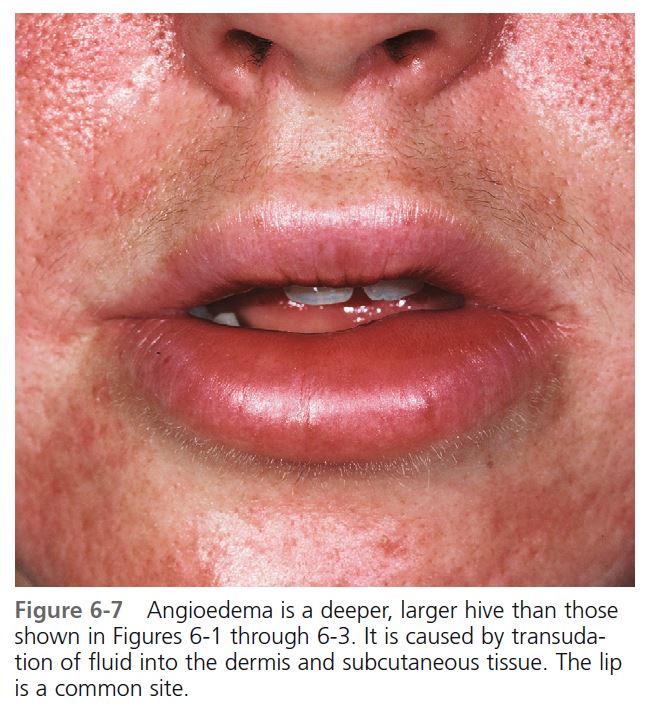

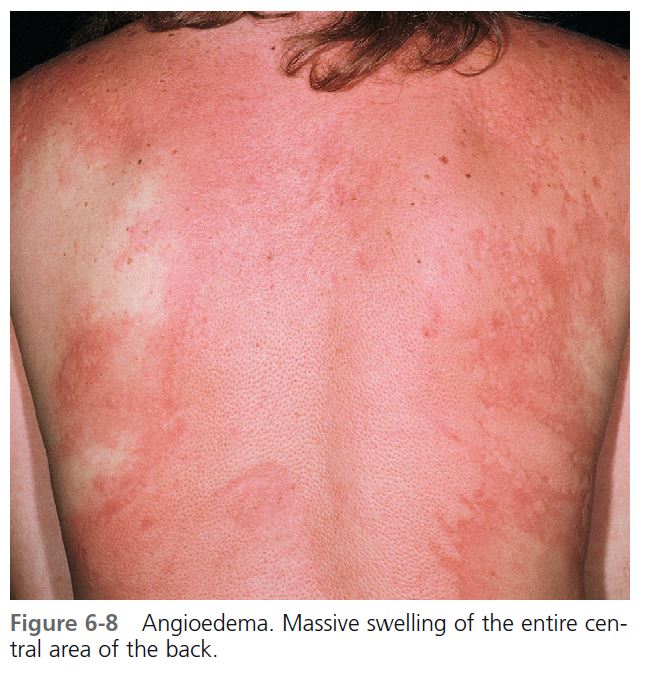

CLINICAL PRESENTATION. Lesions vary in size from the 2- to 4-mm edematous papules of cholinergic urticaria to giant hives, a single lesion of which may cover an extremity. They may be round or oval; when confluent, they become polycyclic ( Figures 6-1 to 6-8 ). A portion of the border either may not form or may be reabsorbed, giving the appearance of incomplete rings (see Figure 6-3 ). Hives may be uniformly red or white, or the edematous border may be red and the remainder of the surface white. This variation in color is usually present in superficial hives; thicker plaques have a uniform color ( Figures 6-1 to 6-6 ).

Hives may be surrounded by a clear or red halo. Thicker plaques that result from massive transudation of fluid into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue are referred to as angioedema. These thick, firm plaques, like typical hives, may occur on any skin surface, but typically involve the lips, larynx (causing hoarseness or a sore throat), and mucosa of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (causing abdominal pain)

(see Figures 6-7 and 6-8 ). Bullae or purpura may appear in areas of intense swelling. Purpura and scaling may result as the lesions of urticarial vasculitis clear. Hives usually have a haphazard distribution, but those elicited by physical stimuli have characteristic features and distribution.

SYMPTOMS. Hives itch. The intensity varies, and some patients with a widespread eruption may experience little itching. Pruritus is milder in deep hives (angioedema) because the edema occurs in areas where there are fewer sensory nerve endings than there are near the surface of the skin.

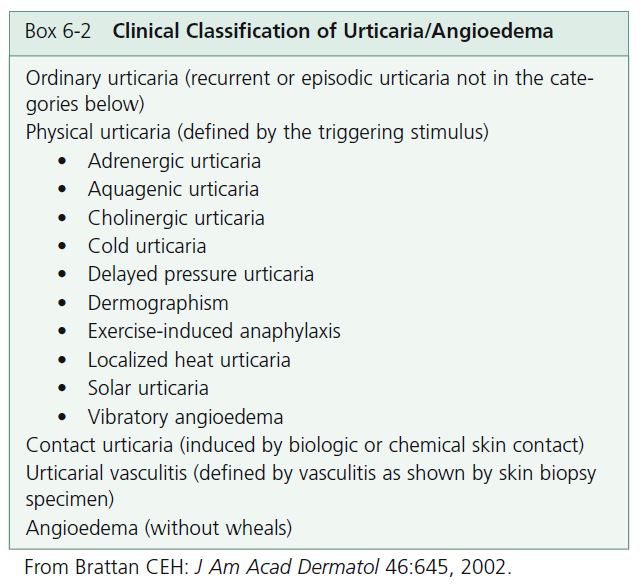

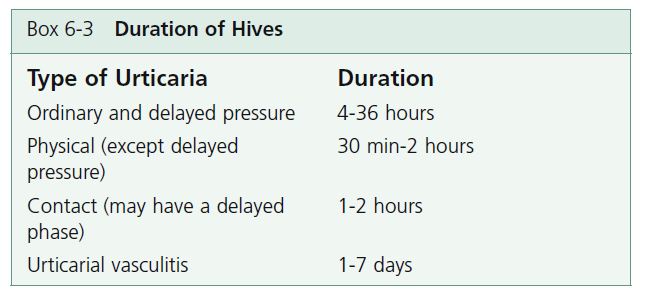

CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION OF URTICARIA/ANGIOEDEMA. The clinical classification of urticaria and angioedema is found in Box 6-2 . Urticaria can be provoked by immunologic and nonimmunologic mechanisms, as well as physical stimuli, skin contact, or small vessel vasculitis. Physical and ordinary urticarias may coexist. Angioedema occurs with or without urticaria. Angioedema without urticaria may indicate a C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency. The duration of hives is also an important diagnostic feature ( Box 6-3 ).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

HISTAMINE

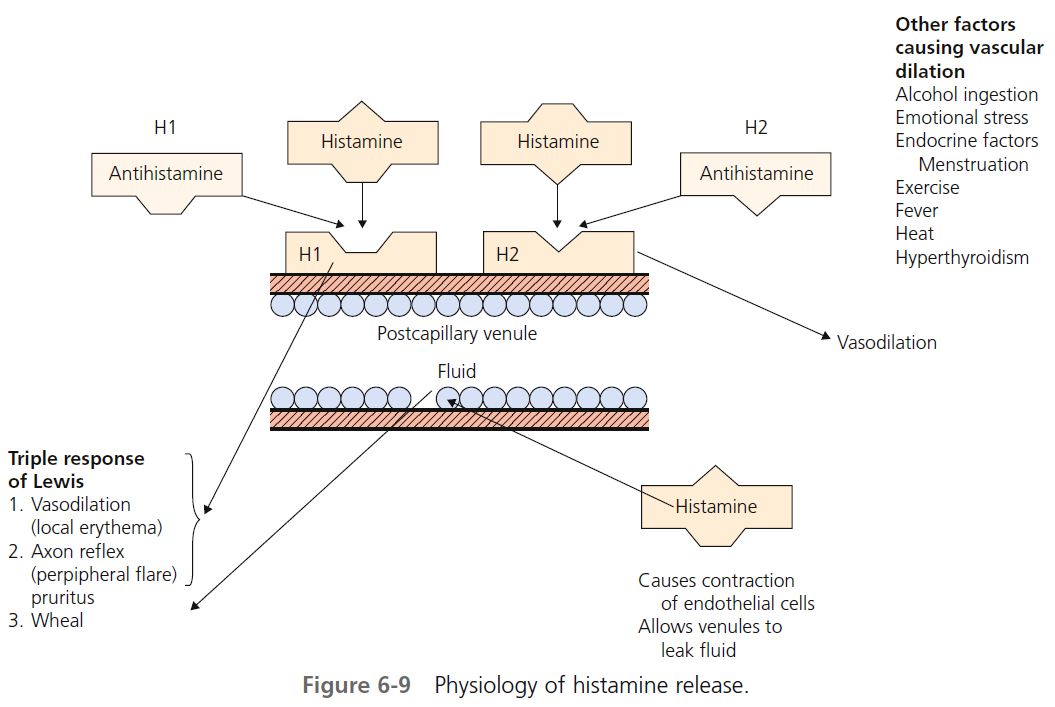

Histamine is the most important mediator of urticaria. Histamine is produced and stored in mast cells. There are several mechanisms for histamine release via mast cell surface receptors. A variety of immunologic, nonimmunologic, physical, and chemical stimuli may be responsible for the degranulation of mast cell granules and the release of histamine into the surrounding tissue and circulation. About one third of patients with chronic urticaria have circulating functional histamine-releasing immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies that bind to the high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI). Release of mast cell mediators can cause inflammation and accumulation and activation of other cells, including eosinophils, neutrophils, and possibly basophils. Histamine causes endothelial cell contraction, which allows vascular fl uid to leak between the cells through the vessel wall, contributing to tissue edema and wheal formation.

When injected into skin, histamine produces the “triple response” of Lewis, the features of which are local erythema (vasodilation), the fl are characterized by erythema beyond the border of the local erythema, and a wheal produced from leakage of fl uid from the postcapillary venule. Histamine induces vascular changes by a number of mechanisms ( Figure 6-9 ). Blood vessels contain two (and possibly more) receptors for histamine. The two most studied are designated H 1 and H 2 .

H 1 RECEPTORS. H 1 receptors, when stimulated by histamine, cause an axon reflex, vasodilation, and pruritus. Acting through H 1 receptors, histamine causes smooth muscle contraction in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts and pruritus and sneezing by sensory nerve stimulation. H 1 receptors are blocked by the vast majority of clinically available antihistamines called H 1 antagonists (e.g., chlorpheniramine), which occupy the receptor site and prevent attachment of histamine.

H 2 RECEPTORS. When H 2 receptors are stimulated, vasodilation occurs. H 2 receptors are also present on the mast cell membrane surface and, when stimulated, further inhibit the production of histamine. Activation of H 2 receptors alone increases gastric acid secretion. Cimetidine (Tagamet), ranitidine (Zantac), and famotidine (Pepcid) are H 2 blocking agents (antihistamines). H 2 receptors are present at other sites. Activation of both H 1 and H 2 receptors causes hypotension, tachycardia, fl ushing, and headache. The H 2 blocking agents are used most often to suppress gastric acid secretion. They are used occasionally, usually in combination with an H 1 blocking agent, to treat urticaria.

INITIAL EVALUATION OF ALL PATIENTS WITH URTICARIA

1. Determine by skin examination that the patient actually has urticaria and not bites.

2. Rule out the presence of physical urticaria to avoid an unnecessarily lengthy evaluation. Stroking the arm with the wood end of a cotton-tipped applicator will test for dermographism.

3. Determine whether hives are acute or chronic. The difference in duration has been arbitrarily set at 6 weeks. Acute urticaria involves episodes of urticaria that last less than 6 weeks. Chronic urticaria consists of recurrent episodes of widespread urticaria present for longer than 6 weeks.

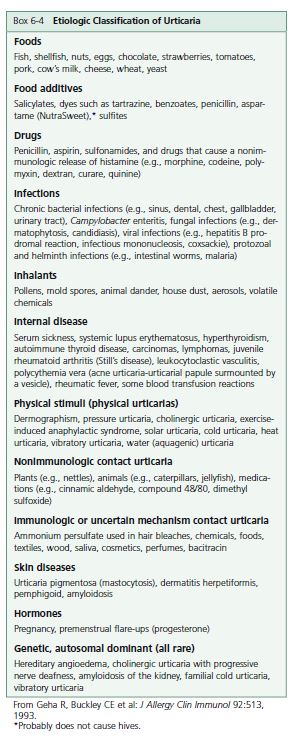

4. Review the known causes of urticaria listed in Box 6-4 (Etiologic Classifi cation of Urticaria). Knowledge of the etiologic factors helps to direct the history and physical examination.

ACUTE URTICARIA

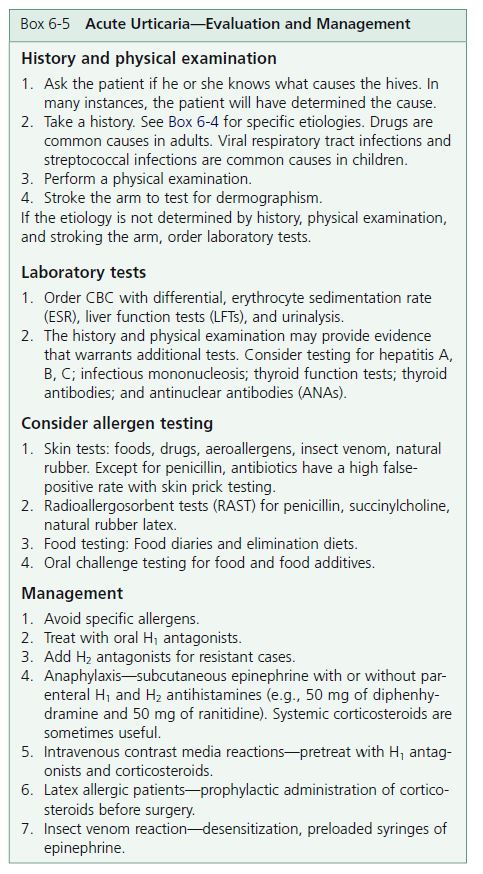

If the urticaria has been present for less than 6 weeks, it is considered acute ( Figure 6-10 ). The evaluation and management of acute urticaria are outlined in Box 6-5 . A history and physical examination should be performed, and laboratory studies are selected to investigate abnormalities. Histamine release that is induced by allergens (e.g., drugs, foods, or pollens) and mediated by IgE is a common cause of acute urticaria, and particular attention should be paid to these factors during the initial evaluation. There are no routine laboratory studies for the evaluation of acute urticaria. Once all possible causes are eliminated, the patient is treated with antihistamines to suppress the hives and stop the itching. Because urticaria clears spontaneously in most patients, an extensive workup is not advised during the early weeks of a urticarial eruption.

CHILDREN WITH HIVES. Food origin is important in the etiology of infantile urticaria. In one series it accounted for 62% of patients, more often than drug etiology (22%), physical urticaria (8%), and contact urticaria (8%).

ETIOLOGY OF ACUTE URTICARIA

Acute urticaria is IgE-mediated, complement-mediated, or nonimmune-mediated.

IgE-MEDIATED REACTIONS. Type I hypersensitivity reactions are probably responsible for most cases of acute urticaria. Circulating antigens such as foods, drugs, or inhalants interact with cell membrane–bound IgE to release histamine. Food allergies are present in 8% of children less than 3 years of age and in 2% of adults. Food allergies are the most common cause of anaphylaxis. Yellow jackets are the most common cause of insect sting–induced urticaria/anaphylaxis in the United States. Latex-induced urticaria is an IgE-mediated reaction.

COMPLEMENT-MEDIATED, OR IMMUNE-COMPLEXMEDIATED, ACUTE URTICARIA. Complement-mediated acute urticaria can be precipitated by administration of whole blood, plasma, immunoglobulins, and drugs or by insect stings. Type III hypersensitivity reactions (Arthus reactions) occur with deposition of insoluble immune complexes in vessel walls. The complexes are composed of IgG or IgM with an antigen such as a drug. Urticaria occurs when the trapped complexes activate complement to cleave the anaphylotoxins C5a and C3a from C5 and C3. C5a and C3a are potent releasers of histamine from mast cells. Serum sickness (fevers, urticaria, lymphadenopathy, arthralgias, and myalgias), urticarial vasculitis, and systemic lupus erythematosus are diseases in which hives may occur as a result of immune complex deposition.

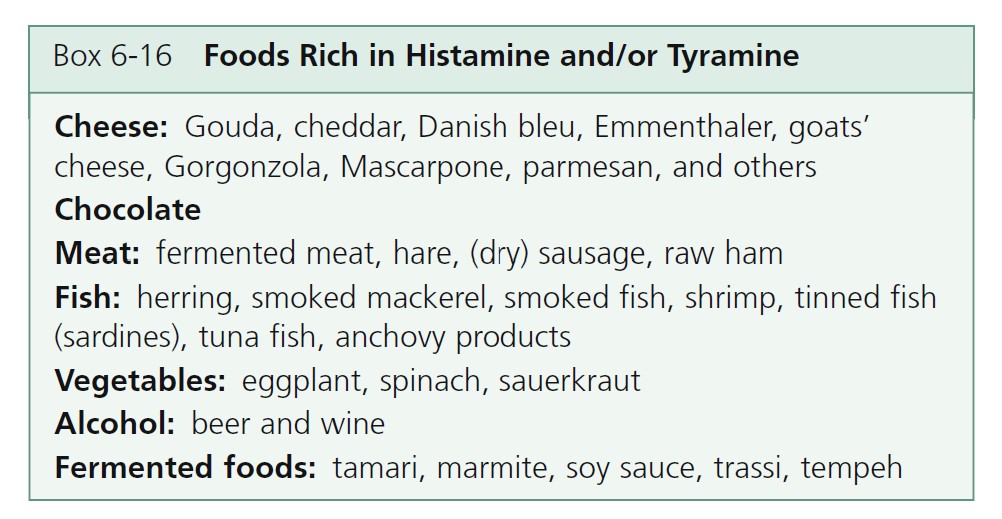

NONIMMUNOLOGIC RELEASE OF HISTAMINE. Pharmacologic mediators, such as acetylcholine, opiates, polymyxin B, and strawberries, react directly with cell membrane–bound mediators to release histamine. Aspirin/NSAIDs cause a nonimmunologic release of histamine. Patients with aspirin/NSAID sensitivity may have a history of allergic rhinitis or asthma. Urticaria may be caused by histamine-containing foods. Fish of the Scombroidea family accumulate histamine during spoilage. The mechanism of radiocontrast-related urticaria/anaphylaxis is unknown. Incidence varies from 3.1% with newer, lower osmolar agents to 12.7% with older, higher osmolar agents. Atopy is a risk factor for urticaria developing after radiocontrast exposure. The physical urticarias may be induced by both direct stimulation of cell membrane receptors and immunologic mechanisms.

CHRONIC URTICARIA

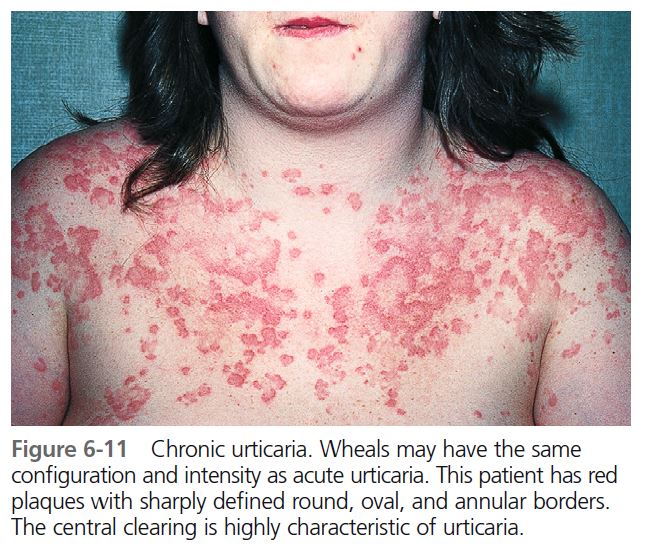

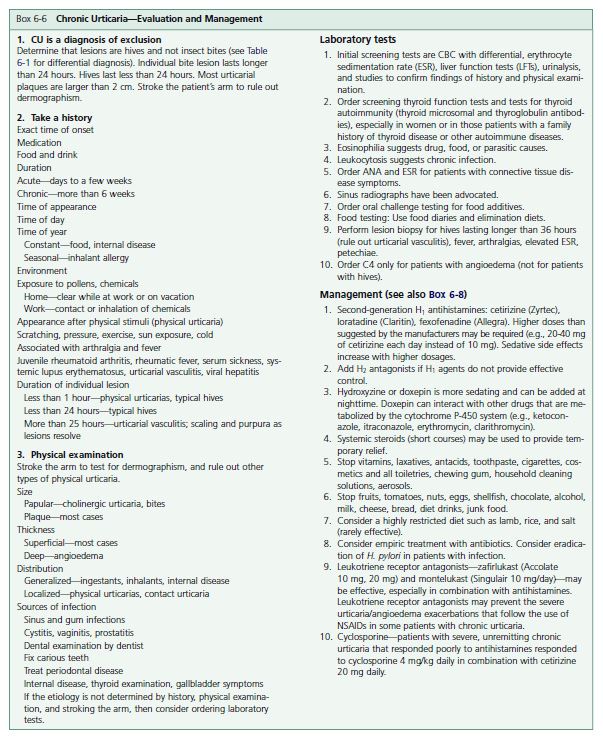

Patients who have a history of hives lasting for 6 or more weeks are classifi ed as having chronic urticaria (CU). The etiology is often unclear. The morphology is similar to that of acute urticaria ( Figure 6-11 ). CU is more common in middle-aged women and is infrequent in children. Individual lesions remain for less than 24 hours, and any skin surface can be affected. Itching is worse at night. Respiratory and gastrointestinal complaints are rare. Angioedema occurs in 50% of cases. Angioedema with chronic urticaria differs from hereditary angioedema in that it rarely affects the larynx. CU patients may experience physical urticaria. Symptoms continue for weeks, months, or years. Pressure urticaria, chronic urticaria, and angioedema frequently occur in the same patient. In one study, delayed pressure urticaria was present in 37% of patients with chronic urticaria. Aspirin/NSAIDs, penicillin, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, opiates, alcohol, febrile illnesses, and stress exacerbate urticaria.

PATHOGENESIS

Chronic urticaria results from the cutaneous mast cell release of histamine. In contrast to acute urticaria, exogenous triggers are not found in most cases. Chronic urticaria in many cases may be an immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Release can be induced by specifi c immunoglobulin E (IgE), components of complement activation and endogenous peptides, endorphins, and enkephalins. Over 30% of chronic urticaria patients have autoimmune phenomena characterized by positive autologous serum skin tests, antibodies to the alpha subunit of the basophil IgE receptor and to IgE, and thyroid autoimmunity. The evaluation and management of chronic urticaria is outlined in Box 6-6 .

The patient must understand that the course of this disease is unpredictable; it may last for months or years. During the evaluation, the patient should be assured that antihistamines will decrease discomfort. The patient should also be told that although the evaluation may be lengthy and is often unrewarding, in most cases the disease ends spontaneously. Patients who understand the nature of this disease do not become discouraged so easily, nor are they as apt to go from physician to physician seeking a cure.

There are many studies in the literature on chronic urticaria. Most demonstrate that if the cause is not found after investigation of abnormalities elicited during the history and physical examination, there is little chance that it will be determined. It is tempting to order laboratory tests such as antinuclear antibody (ANA) levels and stool examinations for ova and parasites in an effort to be thorough, but results of studies do not support this approach. There are certain tests and procedures that might be considered when the initial evaluation has proved unrewarding.

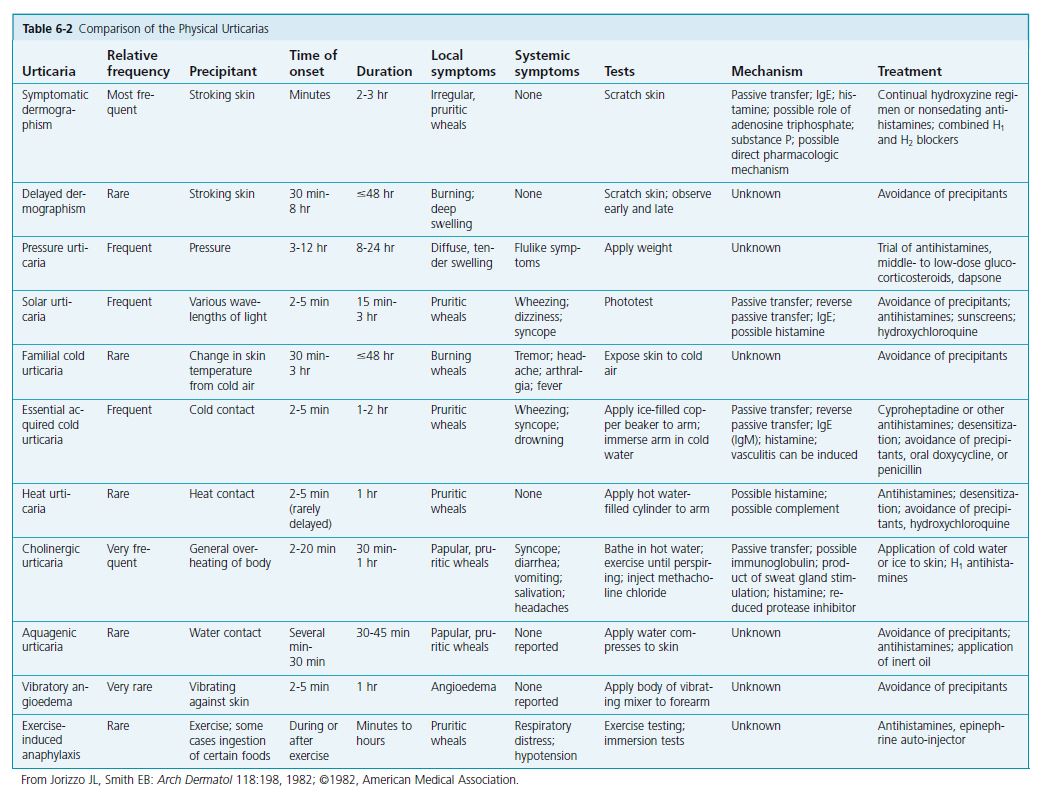

RULE OUT PHYSICAL URTICARIAS. Unrecognized physical urticarias (see p. 194 ) may account for approximately 10% of all cases of chronic urticaria. In one large study physical urticarias were present in 71% of patients with chronic urticaria: 22% had immediate dermographism, 37% had delayed pressure urticaria, 11% had cholinergic urticaria, and 2% had cold urticaria.

The presence of physical urticaria should be ruled out by history and appropriate tests (see Table 6-2 ) before a lengthy evaluation and treatment program is undertaken. Dermographism is the most common type of physical urticaria; it begins suddenly following drug therapy or a viral illness, lasts for months or years, and clears spontaneously. Wheals that appear after the patient’s arm is stroked prove the diagnosis.

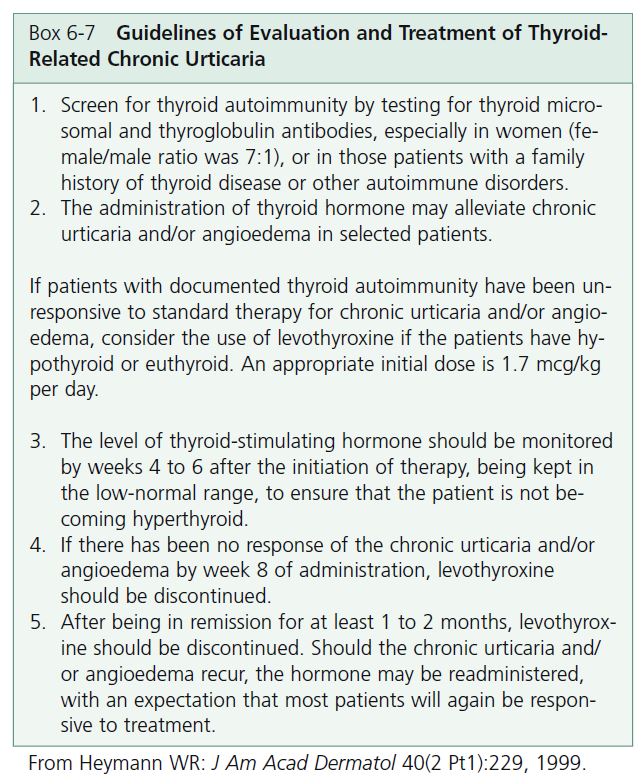

THYROID AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE. There is a significant association between chronic urticaria and autoimmune thyroid disease (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter). Thyroid autoimmunity was found in 12% of 140 consecutively seen patients with chronic urticaria in one series; 88% were women. Most patients with thyroid autoimmunity are asymptomatic and have thyroid function that is normal or only slightly abnormal. Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of thyroid-related urticaria are presented in Box 6-7 .

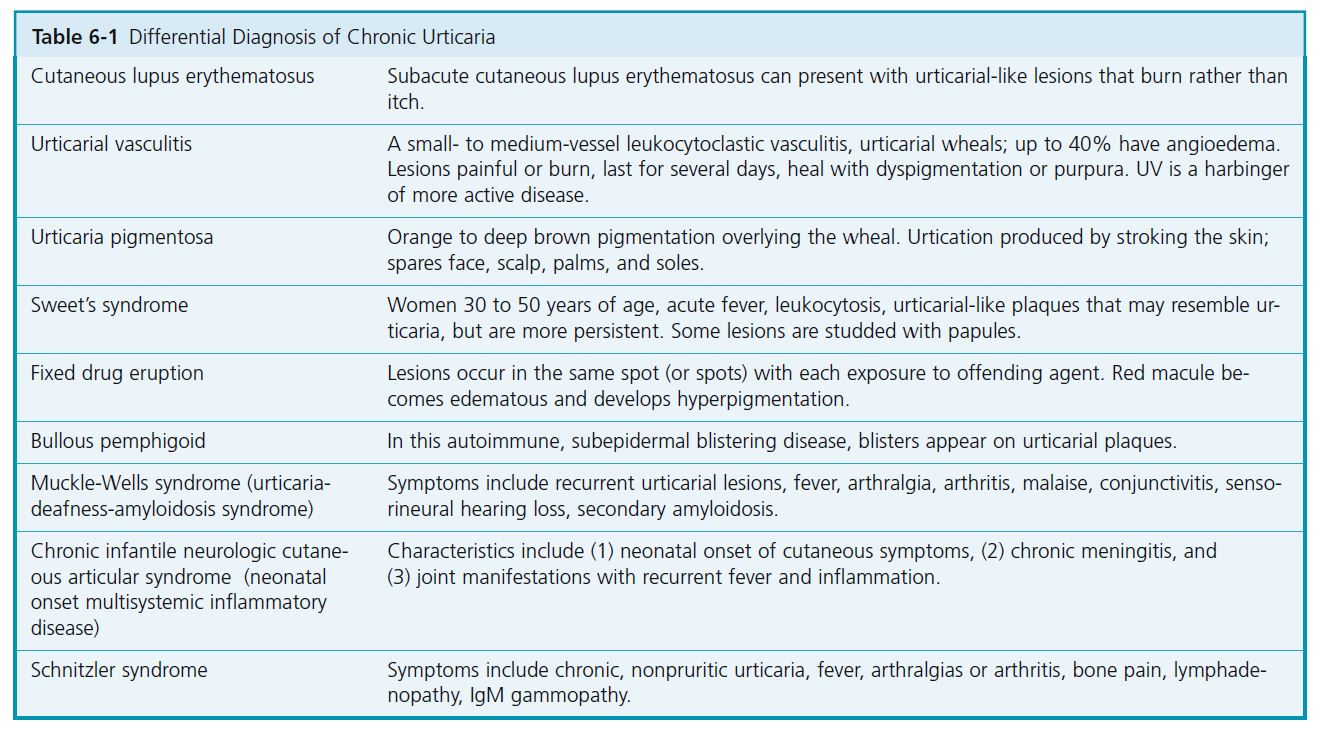

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of chronic urticaria includes diseases that have lesions that mimic urticaria ( Table 6-1 ). These often have fixed urticarial lesions that have some atypical features, such as duration greater than 24 hours, relative lack of itch, or epithelial changes (e.g., hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, vesicles or blisters, or scaling). PMID: 18426134

CHANGE OF ENVIRONMENT. Because the environment consists of numerous antigens, patients should consider a trial period of 1 or 2 weeks of separation from home and work, preferably with a geographic change.

HIGHLY RESTRICTED DIET. A highly restricted diet may be attempted. Patients are fed lamb, rice, sugar, salt, and water for 5 days. The occurrence of new hives after 3 days suggests that foods have no role. If hives disappear, a new food is reintroduced every other day until hives appear.

TREATMENT OF OCCULT INFECTIONS. Patients occasionally respond to antibiotics even in the absence of clinical infection. Consider eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with infection.

SKIN BIOPSY. Urticarial reactions display a wide spectrum of changes, ranging from a mild, mixed dermal inflammatory response to true vasculitis. Patients with hives that are characteristic of urticarial vasculitis should have a biopsy taken of the urticarial plaque. These hives burn rather than itch and last longer than 24 hours.

Dermal edema and dilated lymphatic and vascular capillaries occur. Increased numbers of neutrophils and eosinophils occur in patients with acute urticaria and in those with delayed pressure urticaria. Mast cell numbers are higher in the dermis of lesional and uninvolved skin of all patients with urticaria. Mononuclear infiltrates are more pronounced in cold urticaria and chronic urticaria.

TREATMENT OF URTICARIA

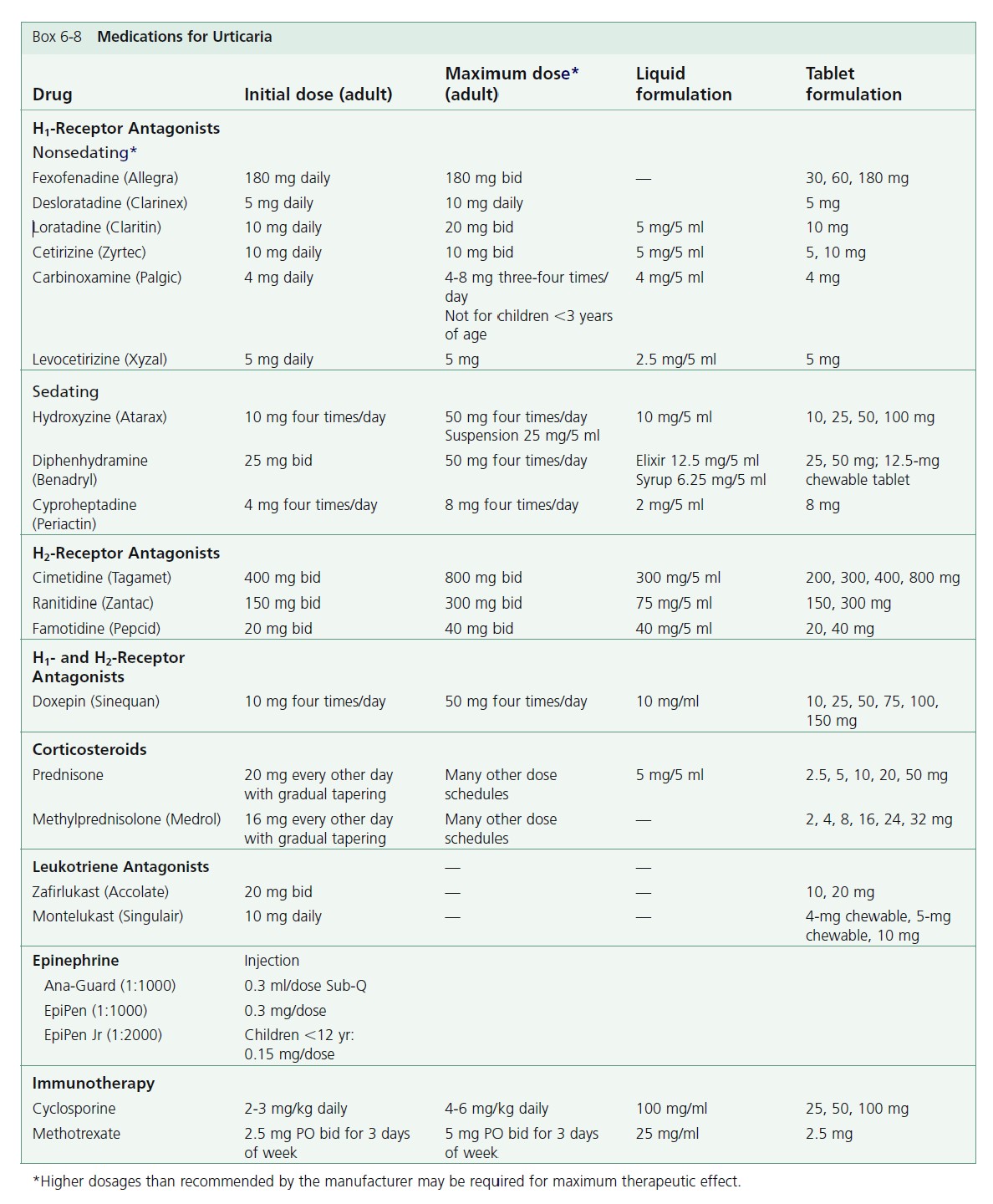

Box 6-8 lists the medications used to treat urticaria.

Approach to treatment

FIRST-LINE THERAPY

Nonsedating H 1 antihistamines (e.g., Allegra 180 mg daily) are the first choice for treatment. Older sedating H 1 antihistamines are more effective and so should be used to treat severe urticaria (e.g., 100 to 200 mg of hydroxyzine or diphenhydramine per day). For patients with severe angioedema (involving swelling of the face, tongue, and pharynx), diphenhydramine is particularly effective.

Patients become accustomed to the sedating effects after about a week, but their performance on driving tests remains impaired. H 2 -receptor antagonists have very few side effects and may be useful as adjunctive therapy. Leukotriene antagonists are considered safe and are worth trying, but severe disease may require prednisone; many regimens have been suggested.

One approach is to start prednisone at 15 to 20 mg as a single morning dose every other day gradually tapering to 2.5 to 5.0 mg every 3 weeks, depending on the patient’s response, and discontinue after 4 to 5 months. Side effects are minimized with the use of dietary discretion and exercise. Some patients require a combination of all of these medications.

Patients who have no response to any of these approaches may respond to immunotherapy with 200 to 300 mg of cyclosporine per day or methotrexate.

ANTIHISTAMINES. For the majority of patients, acute and chronic urticaria may be controlled with antihistamines.

MECHANISM OF ACTION. Antihistamines control urticaria by inhibiting vasodilation and vessel fluid loss. Antihistamines do not block the release of histamine. If histamine has been released before an antihistamine is taken, the receptor sites will be occupied and the antihistamine will have no effect.

Initiation of treatment. Antihistamines are the preferred initial treatment for urticaria and angioedema. Cetirizine, loratadine, or fexofenadine are first-line agents and are given once daily. Higher doses than suggested by the manufacturers may be required; see the box on medications for urticaria ( Box 6-8 ). Patients with daytime and nighttime symptoms can be treated with combination therapy. These patients can be treated with a low-sedating antihistamine in the morning (e.g., loratadine 10 mg, or fexofenadine 180 mg, or cetirizine 10 to 20 mg) and a sedating antihistamine (e.g., hydroxyzine 25 mg) in the evening. Cetirizine can be mildly sedating. Doxepin is an alternative bedtime medication especially for anxious or depressed patients. The initial dose is 10 to 25 mg. Gradually increase the dose up to 75 mg for optimal control. Some patients with chronic urticaria respond when an H 2 -receptor antagonist such as cimetidine is added to conventional antihistamines. This may be worth trying in refractory cases.

Side effects. Antihistamines are structurally similar to atropine; therefore they produce atropine-like peripheral and central anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, and dizziness. First-generation antihistamines (H 1 -receptor antagonists) such as chlorpheniramine, hydroxyzine, and diphenhydramine cross the bloodbrain barrier and produce sedation. There is marked individual variation in response and side effects. Antihistamines may produce stimulation in children, especially in those ages 6 through 12.

Long-term administration. Prolonged use of H 1 antagonists does not lead to autoinduction of hepatic metabolism. The efficacy of H 1 -receptor blockade does not decrease with prolonged use. Tolerance of adverse central nervous system effects may or may not develop.

H 1 and H 2 antihistamines. The majority of available antihistamines are H 1 antagonists (i.e., they compete for the H 1 -receptor sites). Cimetidine, ranitidine, and famotidine are H 2 antagonists that are used primarily for the treatment of gastric hyperacidity. Approximately 85% of histamine receptors in the skin are the H 1 subtype, and 15% are H 2 receptors. The addition of an H 2 -receptor antagonist to an H 1 -receptor antagonist augments the inhibition of a histamine-induced wheal-and-fl are reaction once H 1 -receptor blockade has been maximized. It would seem that the combination of H 1 and H 2 antihistamines would provide optimum effects. The results of studies are confl icting but generally show that the combination is not much more effective than an H 1 blocking agent used alone.

First-generation (sedating) H 1 antihistamines. The first-generation H 1 antihistamines are divided into five classes (see Box 6-8 ). They are lipophilic, cross the bloodbrain barrier, and cause sedation, weight gain, and atropine-like complications including dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, and dysuria. Metabolism occurs via the hepatic cytochrome P-450 (CYP) system. In patients with liver disease, or in patients who are taking CYP 3A4 inhibitors such as erythromycin or ketoconazole, the plasma half-life may be prolonged. The H 1 antagonists suppress the wheal caused by histamine. Antihistamines given during or after the onset of a hive are less effective. They prevent wheals rather than treat them.

Second-generation (low-sedating) H 1 antihistamines. The second-generation antihistamines are not lipophilic and do not readily cross the blood-brain barrier. They cause little sedation and little or no atropine-like activity.

Fexofenadine (Allegra). Fexofenadine in a single dose of 180 mg daily or 60 mg twice daily is the recommended dosage for treating urticaria. Dosage adjustment is not necessary in the elderly or in patients with mild renal or hepatic impairment. Fexofenadine may offer the best combination of effectiveness and safety of all of the low-sedating antihistamines. A dose that is higher than recommended may be required.

Cetirizine (Zyrtec). Cetirizine is a metabolite of the first generation H 1 antihistamine hydroxyzine. Some patients notice drowsiness after a 10-mg dose. The adult dose is 10 mg daily. A reduced dosage (5 mg daily) is recommended in patients with chronic renal or hepatic impairment. No drug interactions are reported, and there is no cardiotoxicity. A dose higher than recommended may be required.

Loratadine (Claritin). Loratadine is long-acting. A 10-mg dose suppresses whealing for up to 12 hours; suppression lasts longer after a larger dosage. A reduced dosage may be required in patients with chronic liver or renal disease. There are no significant adverse drug interactions. A special form of the medication, Reditabs (10 mg), rapidly disintegrates in the mouth. A dose higher than recommended may be required.

Desloratadine (Clarinex). Desloratadine is an active metabolite of loratadine. A 5-mg dose each day is effective. There is no evidence that it offers any advantage over loratadine.

Tricyclic antihistamines (Doxepin). Tricyclic antidepressants are potent blockers of histamine H 1 and H 2 receptors. The most potent is doxepin. When taken in dosages between 10 and 25 mg three times a day, doxepin is effective for the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria. Few side effects occur at this low dosage. Higher dosages may be tolerated if taken in the evening. Doxepin is a good alternative for patients with chronic urticaria who are not controlled with conventional antihistamines and for patients who suffer anxiety and depression associated with chronic urticaria. Lethargy is commonly observed but diminishes with continued use. Dry mouth and constipation are also commonly observed. Doxepin can interact with other drugs that are metabolized by the cytochrome P-450 system (e.g., ketoconazole, itraconazole, erythromycin, clarithromycin).

EPINEPHRINE. Severe urticaria or angioedema requires epinephrine. Epinephrine solutions have a rapid onset of effect but a short duration of action. The dosage for adults is a 1:1000 solution (0.2 to 1.0 ml) given either subcutaneously or intramuscularly; the initial dose is usually 0.3 ml. The epinephrine suspensions provide both a prompt and a prolonged effect (up to 8 hours). For adults, 0.1 to 0.3 ml of the 1:200 suspension is given subcutaneously.

SECOND-LINE AGENTS

ORAL CORTICOSTEROIDS. Many patients with chronic urticaria and angioedema will have little response to even a combination of H 1 - and H 2 -receptor blockers. Oral corticosteroids should be considered for these refractory cases. Because of toxicity, corticosteroids are reserved for antihistamine failures or the most severe cases. They are reliable and effective. They do not have the potential for drug-free remission. Prednisone 40 mg per day given in a single morning dose or 20 mg twice a day is effective in most cases. Another approach is to prescribe 30 20-mg tablets. The patient receives 5 days each of 60 mg, 40 mg, and 20 mg, and the medication is taken once each morning. Others will respond to prednisone 20 mg every other day with a gradual taper.

LEUKOTRIENE MODIFIERS. Leukotriene modifiers may provide improvement in some cases of antihistamine resistant chronic urticaria. Excellent safety, absence of required monitoring in the cases of montelukast and zafirlukast, and wide availability make leukotriene modifi ers the preferred alternative agent. Montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton have been studied. Response may take days to weeks. Randomized controlled trials show zafirlukast and montelukast either singly or in combination with antihistamines are effective but several negative studies have also appeared. Montelukast was demonstrated to be effective for patients with NSAID-exacerbated chronic urticaria. Patients with positive autologous serum skin test (ASST) results may predict better response to leukotriene modifiers. Experience in physical urticarias has also been promising.

DAPSONE. Small studies demonstrate excellent clinical response with dosages that vary from 25 mg/day to 100 mg/day. Response may be fairly rapid, but some patients require several weeks to notice improvement. Monitor for the predictable small decline in hemoglobin level. The drug is generally well tolerated. There is a possibility of sustained remission after stopping the drug. Obtain a G6PD level to avoid more severe hemolytic anemia in G6PD-deficient patients.

CALCINEURIN INHIBITORS. Cyclosporine might be an effective alternative in some chronic urticaria patients unresponsive to conventional treatments and may be considered if leukotriene modifiers and dapsone fail. Patients with severe unremitting disease who respond poorly to antihistamines may respond to 4 mg/kg daily of cyclosporine for 4 weeks. Patients requiring initially high doses of glucocorticosteroids and with a long clinical history are less amenable to cyclosporine treatment.

THIRD-LINE AGENTS

INTRAVENOUS IMMUNOGLOBULIN. Responses ranging from complete and lasting remission to modest transient benefit are reported. Response seems to be rapid. The optimal dose and number of infusions to attempt are unclear. Only case reports and short series of patients are reported.

METHOTREXATE. Methotrexate may be considered in resistant cases of urticaria. Case reports and a small series of patients document benefi t within 1 to 2 weeks of starting methotrexate. Because adverse effects may be serious and frequent monitoring is necessary, methotrexate should be reserved for intractable cases in which other alternative agents have failed. Methotrexate 10 to 15 mg weekly or 2.5 mg twice a day for 3 days of the week would be a reasonable starting dose.

TOPICAL MEASURES. Itching is controlled with tepid showering, tepid oatmeal baths (Aveeno), cooling lotions that contain menthol (Sarna lotion), and topical pramoxine lotions (Itch-X). Avoid factors that enhance pruritus (e.g., aspirin, drinking alcohol, or wearing of tight elasticized apparel or coarse woolen fabrics).

PHYSICAL URTICARIAS

Physical urticarias are induced by physical and external stimuli, and they typically affect young adults. More than one type of physical urticaria can occur in an individual. Provocative testing confi rms the diagnosis. During the initial examination, the physician should determine whether the hives are elicited by physical stimuli (see Table 6-2 ). Patients with these distinctive hives may be spared a detailed laboratory evaluation; they simply require an explanation of their condition and its treatment. Unrecognized physical urticarias may account for approximately 20% of all cases of chronic urticaria. A major distinguishing feature of the physical urticarias is that attacks are brief, lasting only 30 to 120 minutes. In typical urticaria, individual lesions last from hours to a few days. The one exception among physical urticarias is pressure urticaria, in which

swelling may last for several hours. Most physical urticaria forms persist for about 3 to 5 years or longer.

Dermographism

Also known as “skin writing,” dermographism is the most common physical urticaria, occurring to some degree in approximately 5% of the population. Scratching, toweling, or other activities that produce minor skin trauma induce itching and wheals. The onset is usually sudden; young patients are affected most commonly. The tendency to be dermographic lasts for weeks to months or years. The condition runs on average a course of 2 to 3 years before resolving spontaneously. It may be preceded by a viral infection, antibiotic therapy (especially penicillin), or emotional upset, but in most cases the cause is unknown. Mucosal involvement and angioedema do not occur. There are no recognized systemic associations (such as atopy or autoimmunity).

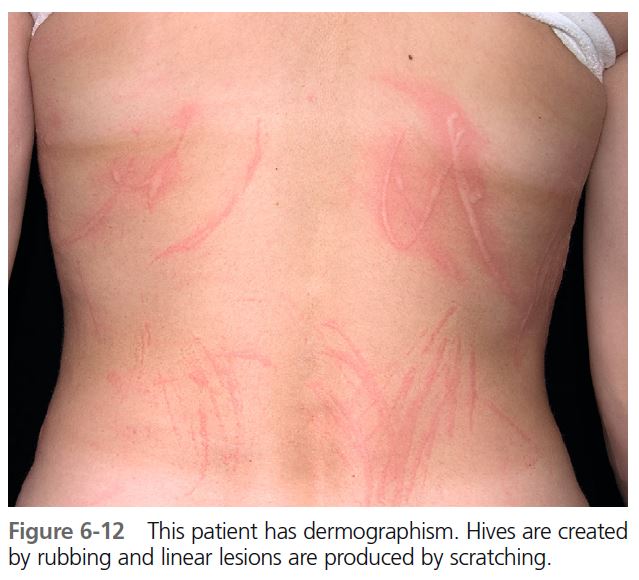

The degree of urticarial response varies. A patient will be highly reactive for months and then appear to be in remission, only to have symptoms recur ( Figure 6-12 ). Patients complain of linear, itchy wheals from scratching or wheals at the site of friction from clothing. Delayed dermographism, in which the immediate urticarial response is followed in 1 to 6 hours by a wheal that persists for 24 to 48 hours, is rare.

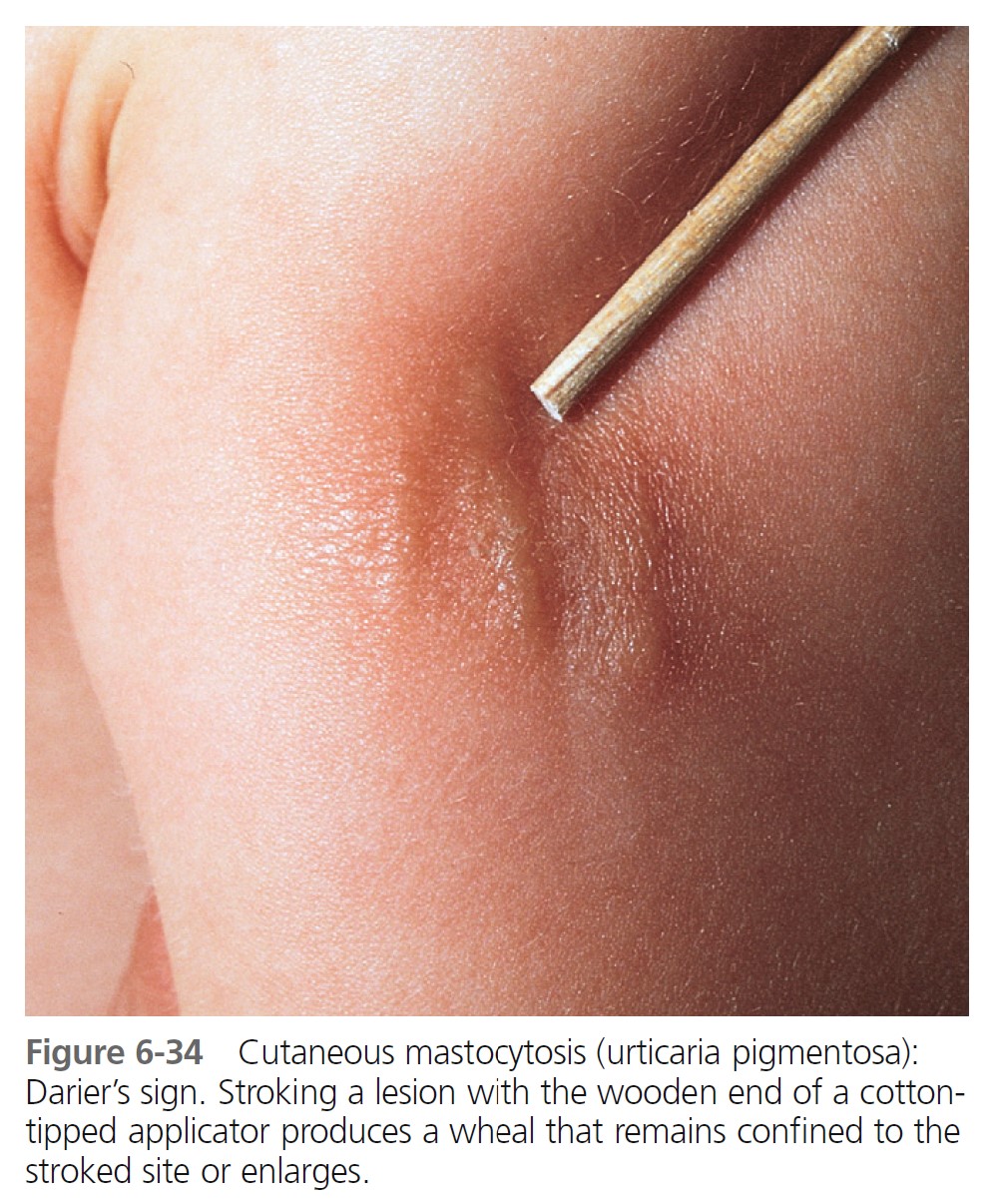

DIAGNOSIS. A tongue blade drawn firmly across the patient’s arm or back produces whealing 2 mm or more in width in approximately 1 to 3 minutes (Darier’s sign), an exaggerated triple response ( Figure 6-13 ).

1. A red line occurs in 3 to 15 seconds (capillary dilation).

2. Broadening erythema appears (axon refl ex fl are from arteriolar dilation).

3. A wheal with surrounding erythema replaces the red line (transudation of fl uid through dilated capillaries).

As a control, the examining physician can perform this test on his or her own arm at the same time.

Unlike urticaria pigmentosa caused by cutaneous mastocytosis (which also manifests dermographism—Darier’s sign), there is no increase in skin mast cell numbers.

TREATMENT. Treatment is not necessary unless the patient is highly sensitive and reacts continually to the slightest trauma. Antihistamines are very effective. Nonsedating H 1 antihistamines or hydroxyzine in relatively low dosages (10 to 25 mg daily to four times a day) provides adequate relief. Some patients are severely affected and require continuous suppression. Use the lowest dose possible to stop itching. Many patients adapt to a low dose of hydroxyzine and do not feel sedated.

Pressure urticaria

A deep, itchy, burning, or painful swelling occurring 2 to 6 hours after a pressure stimulus and lasting 8 to 72 hours is characteristic of this common form of physical urticaria. The mean age of onset is the early 30s. The disease is chronic, and the mean duration is 9 years (range: 1 to 40 years). Malaise, fatigue, fever, chills, headache, or generalized arthralgia may occur. Many have moderate to severe disease that is disabling, especially for those who perform manual labor. Pressure urticaria, chronic urticaria, and angioedema frequently occur in the same patient. In one study delayed pressure urticaria was present in 37% of patients with chronic urticaria. This explains the frequency of wheals at local pressure sites in patients with chronic urticaria. It also explains the poor response to H 1 antihistamines in some patients because delayed pressure urticaria is generally poorly responsive to this treatment.

The hands, feet, trunk, buttock, lips, and face are commonly affected. Lesions are induced by standing, walking, wearing tight garments, or prolonged sitting on a hard surface ( Figures 6-14 and 6-15 ).

DIAGNOSIS. Because the swelling occurs hours after the application of pressure, the cause may not be immediately apparent. Repeated deep swelling in the same area is the clue to the diagnosis. Patients with dermographism may have whealing from pressure that occurs immediately, rather than hours later. Tests using weights are used for studies but generally are not performed in clinical practice.

TREATMENT. Protect pressure points. Systemic steroids given in short duration tapers are the most effective treatment for severe, disabling delayed pressure urticaria. Dosages of prednisone greater than 30 mg/day may be required. Antihistamines are usually not helpful but should be tried. Cetirizine (at a dose of 10 mg daily or higher) is reported to be effective. Cetirizine (10 mg PO daily) and theophylline (200 mg PO bid) are more effective than cetirizine alone. PMID: 16164841

Dapsone (100 to 150 mg daily) can be very effective. Methotrexate (15 mg/week), montelukast, ketotifen plus nimesulide, sulfasalazine, or topical clobetasol propionate 0.5% are reported effective in single case reports.

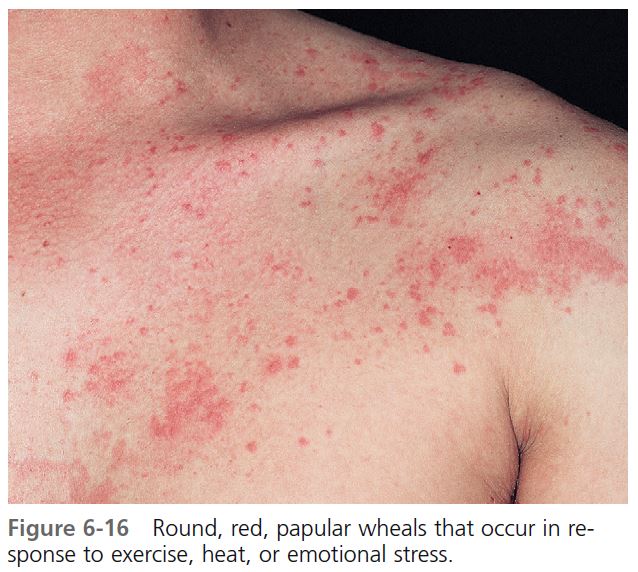

Cholinergic urticaria

In its milder form, “heat bumps,” cholinergic urticaria is the most common of the physical urticarias. It is primarily seen in adolescents and young adults. The overall prevalence is 11.2%; most of the affected persons are older than 20 years. A very small group is severely afflicted. Most persons have mild symptoms that are restricted to fleeting, pinpoint-size wheals. Most affected people do not seek medical attention. Activation of the cholinergic sympathetic innervation of sweat glands is a possible mechanism.

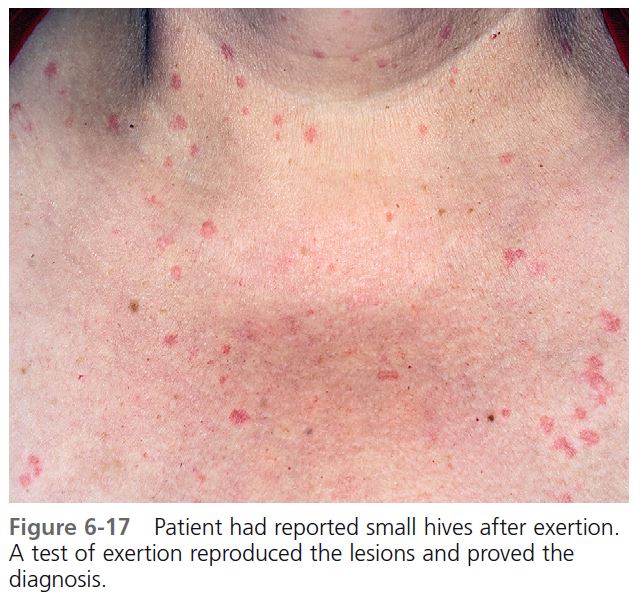

CLINICAL FEATURES. Round, papular wheals 2 to 4 mm in diameter that are surrounded by a slight to extensive red flare are diagnostic of this most distinctive type of hive ( Figures 6-16 and 6-17 ). Typically, the hives occur during or shortly after exercise. However, their onset may be delayed for approximately 1 hour after stimulation. An attack begins with itching, tingling, burning, warmth, or irritation of the skin. Hives begin within 2 to 20 minutes after the patient experiences a general overheating of the body as a result of exercise, exposure to heat, or emotional stress, and they last for minutes to hours (median: 30 minutes). Cholinergic urticaria may become confluent and resemble typical hives. The incidence of systemic symptoms is very low; however, when they occur, systemic systems include angioedema, hypotension, wheezing, and GI tract complaints.

DIAGNOSIS. The diagnosis is suggested by the history and confirmed by experimentally reproducing the lesions. The most reliable and efficient testing method is to ask the patient to run in place or to use an exercise bicycle for 10 to 15 minutes, and then to observe the patient for 1 hour to detect the typical micropapular hives. Exercise testing should be done in a controlled environment; patients with exercise-induced anaphylaxis may need emergency treatment. Immersion of half the patient in a bath at 43° C can raise the patient’s oral temperature by 1° C to 1.5° C and induce characteristic micropapular hives. The immersion test does not induce hives in patients with exercise-induced anaphylaxis.

TREATMENT. Patients can avoid symptoms by limiting strenuous exercise. Showering with hot water may temporarily deplete histamine stores and induce a 24-hour refractory period. Immediate cooling after sweating, such as a cool shower, can abort attacks. Cetirizine (Zyrtec) at twice its recommended dose of 20 mg is very effective. Hydroxyzine (10 to 50 mg) taken 1 hour before exercise attenuates the eruption, but the side effect of drowsiness is often unacceptable. Severely affected unresponsive patients may respond to stanozolol.

Exercise-induced anaphylaxis

Patients develop pruritus, urticaria, respiratory distress, and hypotension after exercise. Symptoms may progress to angioedema, laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, and hypotension, and there is a high frequency of progression to upper airway distress and shock. It is associated with different kinds of exercise, although jogging is the most frequently reported. Exercise acts as a physical stimulus that, through an unknown mechanism, provokes mast cell degranulation and elevated serum histamine levels. In contrast to cholinergic urticaria, the lesions are large and are not produced by hot showers, pyrexia, or anxiety. It is differentiated from cholinergic urticaria by a hot-water immersion test (see Cholinergic urticaria). Exercise-induced anaphylaxis (EIA) or exercise-accentuated anaphylaxis may occur only after ingestion of certain foods such as celery, shellfish, wheat, fruit, milk, and fish (food-dependent EIA). Attacks occur when the patient exercises within 30 minutes after ingestion of the food; eating the food without exercising (and vice versa) causes no symptoms. Patients with wheat-associated EIA have positive skin tests to several wheat fractions. Another precipitating factor includes drug intake; a familial tendency has been reported. The prognosis is not well-defined, but a reduction of attacks occurs in 45% of patients by means of elimination diets and behavioral changes. The differential diagnosis includes exercise-induced asthma, idiopathic anaphylaxis, cardiac arrhythmias, and carcinoid syndrome.

TREATMENT. H 1 antihistamines are recommended as pretreatment and acute therapy. Administration of epinephrine by auto-injector may be required. Exercising with a partner is prudent. Exercise should be stopped if itching, erythema, or whealing occurs. Airway maintenance and cardiovascular support may be required. Prophylactic treatment includes avoidance of exercise, abstention from coprecipitating foods at least 4 hours before exercise, and pretreatment with antihistamines and cromolyn, or the induction of tolerance through regular exercise.

Cold urticaria

Cold urticaria syndromes are a group of disorders characterized by urticaria, angioedema, or anaphylaxis that develops after cold exposure.

PRIMARY ACQUIRED COLD URTICARIA. Primary acquired (“essential”) cold urticaria occurs in children and young adults. Local whealing and itching occur within a few minutes of applying a solid or fluid cold stimulus to the skin. The wheal lasts for about a half hour. Dermographism and cholinergic urticaria are found relatively often in patients with cold urticaria. Urticaria may occur in the oropharynx after a cold drink. Systemic symptoms, occasionally severe and anaphylactoid, may occur after extensive exposure such as immersion in cold water. There may be a recent history of a virus infection ( Mycoplasma pneumoniae ). Spontaneous improvement occurs in an average of 2 to 3 years. Hives occur with a sudden drop in air temperature or during exposure to cold water. Many patients have severe reactions with generalized urticaria, angioedema, or both. Swimming in cold water is the most common cause of severe reactions and can result in massive transudation of fluid into the skin, leading to hypotension, fainting, shock, and possibly death. Like dermographism, cold urticaria often begins after infection, drug therapy, or emotional stress.

SECONDARY ACQUIRED COLD URTICARIA. Secondary acquired cold urticaria occurs in about 5% of patients with cold urticaria. Wheals are persistent, may have purpura, and demonstrate vasculitis on skin biopsy. Cryoglobulin, cold agglutinin, or cryofibrinogens are present. Order complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), antinuclear antibody (ANA), mononucleosis spot test, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), rheumatoid factor, total complement, cryoglobulins, cryofibrinogens, cold agglutinins, and cold hemolysins. Demonstration of a cryoglobulin should prompt a search for chronic hepatitis B or C infection, lymphoreticular malignancy, or glandular fever. The cryoglobulins may be polyclonal postinfection) or monoclonal (IgG or IgM), and complement activation may be involved.

DIAGNOSIS. The diagnosis is made by inducing a hive with a plastic-wrapped ice cube held against the forearm for 3 to 5 minutes ( Figure 6-18 ). Some patients require up to 20 minutes to elicit a response. A cold-water immersion test, in which the forearm is submerged for 5 to 15 minutes in water at 0° to 8° C, establishes the diagnosis when the results of the ice cube test are equivocal. The patient must be monitored closely because severe reactions are possible.

TREATMENT. Patients must learn to protect themselves from a sudden decrease in temperature. Cyproheptadine, loratadine, cetirizine, doxepin, and other antihistamines may be effective. High dosing with antihistamines, up to four times the daily recommended dose, may be required. Antibiotic therapy may be effective even if no underlying infection can be detected. Penicillin (e.g., oral phenoxymethylpenicillin 1 milliunit/day for 2 to 4 weeks or doxycycline 200 mg/day for 3 weeks) is recommended.

Solar urticaria

Hives that occur in sun-exposed areas minutes after exposure to the sun and disappear in less than 1 hour are called solar urticaria. This photoallergic disorder is caused by both sunlight and artificial light. It is most common in young adults; females are more often affected. Systemic reactions that include syncope can occur. Previously exposed tanned skin may not react when exposed to ultraviolet light. Hives induced by exposure to ultraviolet light must be distinguished from the much more common sunrelated condition of polymorphous light eruption. Lesions of polymorphous light eruption are rarely urticarial. They occur hours after exposure and persist for several days.

PATHOGENESIS

Evidence supports an immunologic IgE-mediated mechanism for solar urticaria. There are several different wavelengths that can cause solar urticaria. The disease is classified into six types that correspond to six different wavelengths of light. An individual reacts to a specific wavelength or a narrow band of the light spectrum, usually within the range of 290 to 500 nm. The cause may be an allergic reaction to an antigen formed in the skin by light waves. Those reacting to light wavelengths greater than 400 nm (visible light) develop hives even when exposed through glass. The wavelength responsible for solar urticaria is identified by phototesting. Antihistamines, sunscreens, and graded exposure to increasing amounts of light are effective treatments.

Heat, water, and vibration urticarias

Other physical stimuli such as heat, water of any temperature, or vibration are rare causes of urticaria. Aquagenic urticaria resembles the micropapular hives of cholinergic urticaria. Antihistamine and anticholinergic medication may not prevent the reaction. The mechanism of this phenomenon remains poorly understood.

Aquagenic pruritus

Severe, prickling skin discomfort without skin lesions occurs within 1 to 15 (or more) minutes after contact with water at any temperature and lasts for 10 to 120 minutes (average: 40 minutes). Histamine does not seem to play a key role in the pathogenesis of aquagenic pruritus. Capsaicin cream (Zostrix, Zostrix-HP) applied three times daily for 4 weeks resulted in complete relief of symptoms in the treated areas. Ultraviolet B phototherapy and antihistamines provide some relief. Aquagenic pruritus may be composed of two similar but distinct entities, each of which responds to a different treatment. Some patients with aquagenic pruritus are helped by adding sodium bicarbonate (25 to 200 gm) to the bath water or using the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone. PMID: 16502200 Patients with aquagenic pruritus of the elderly responded to emollients. PMID: 2838535 Polycythemia rubra vera should be ruled out.

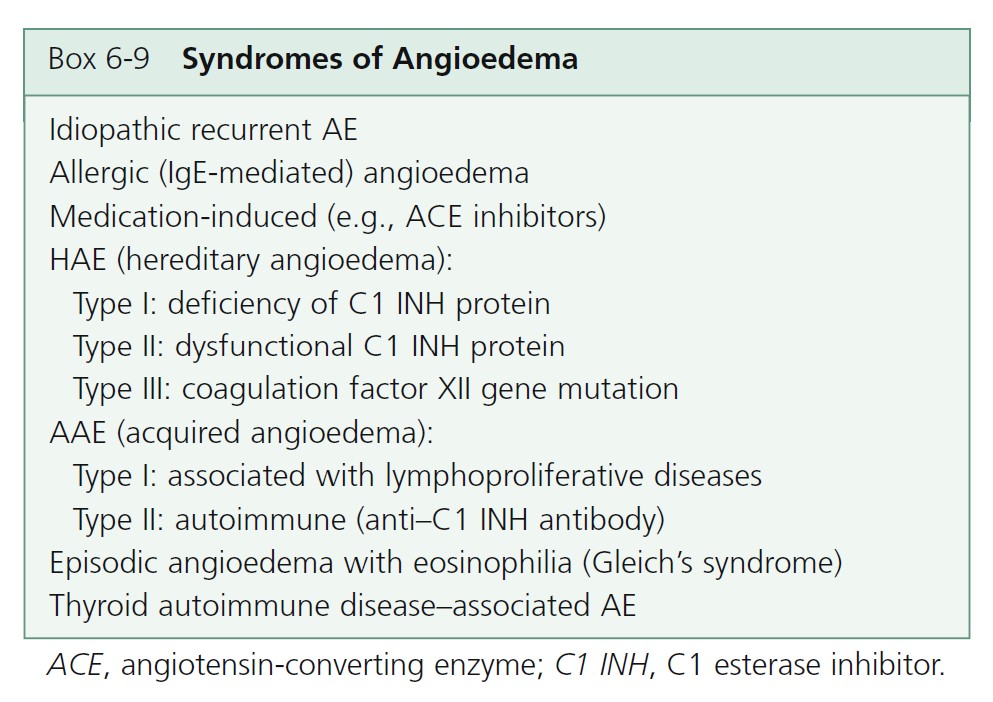

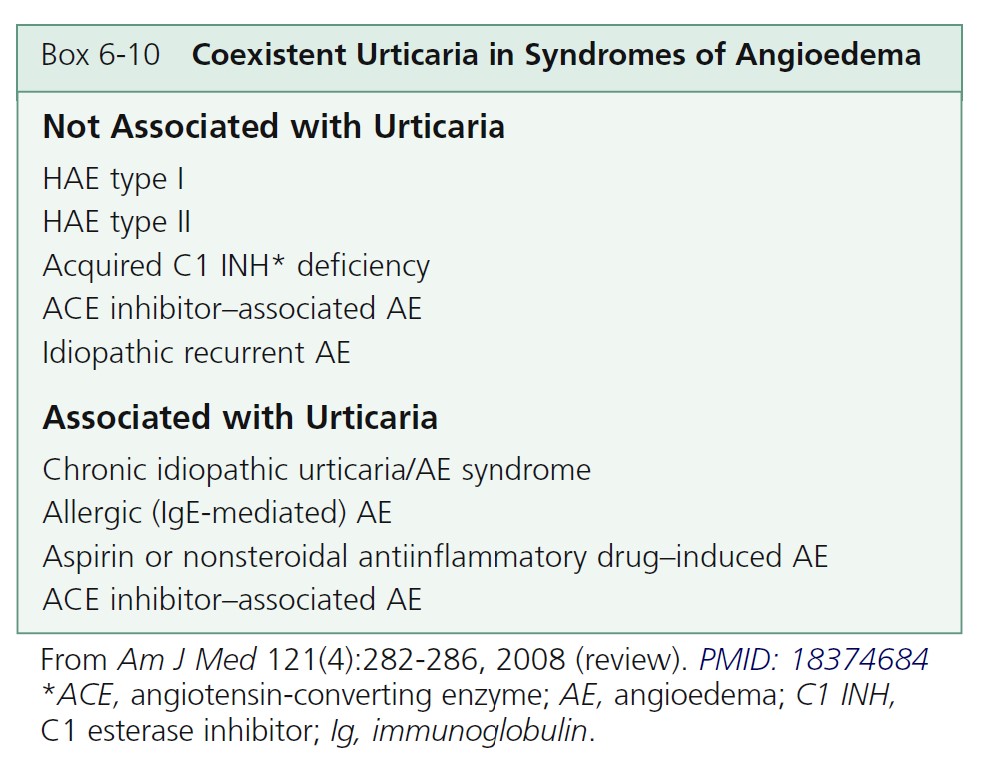

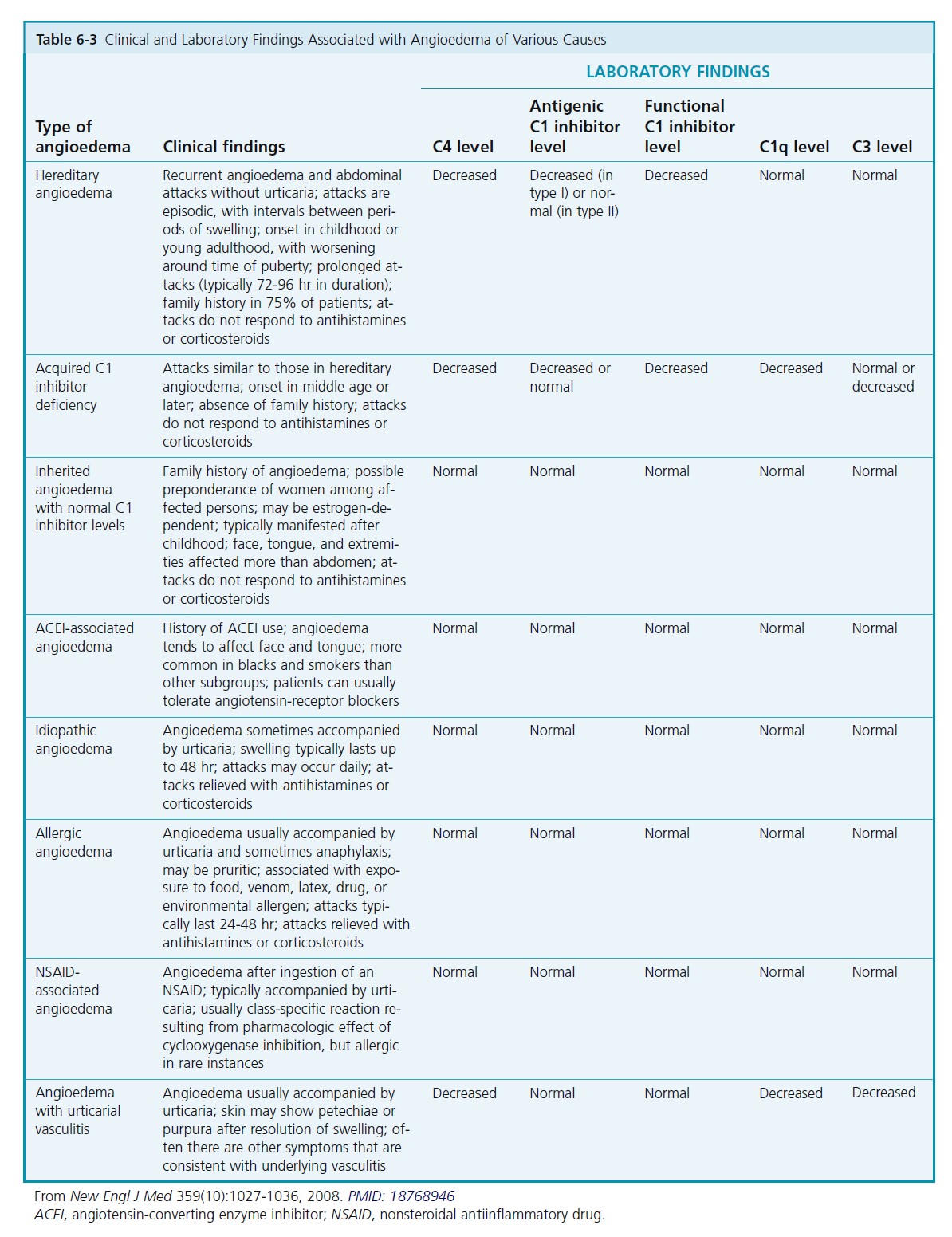

ANGIOEDEMA

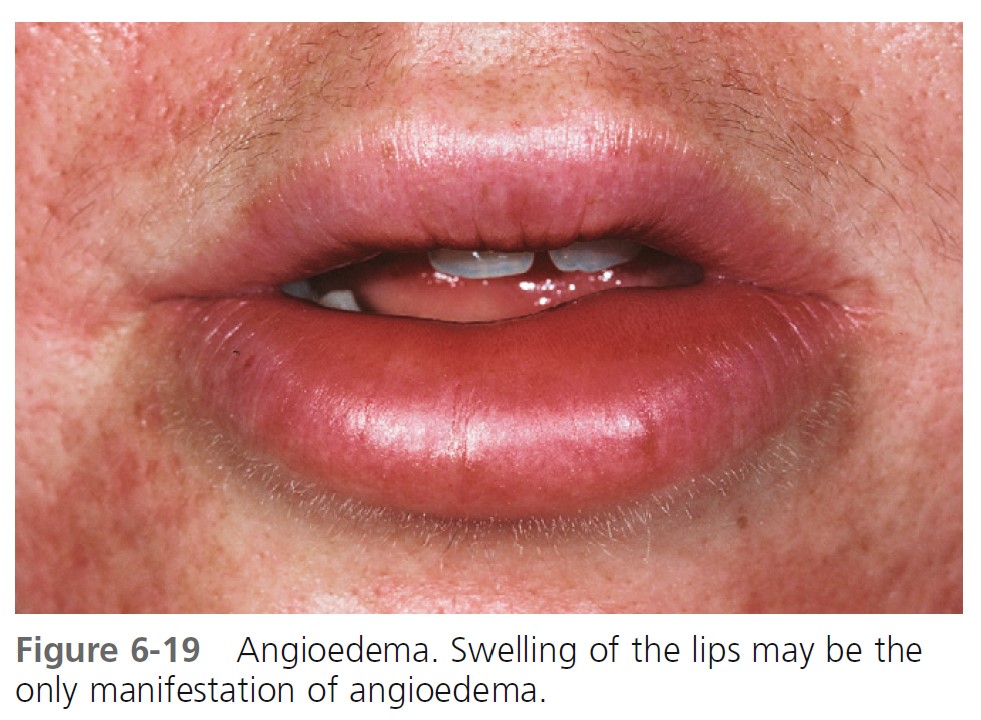

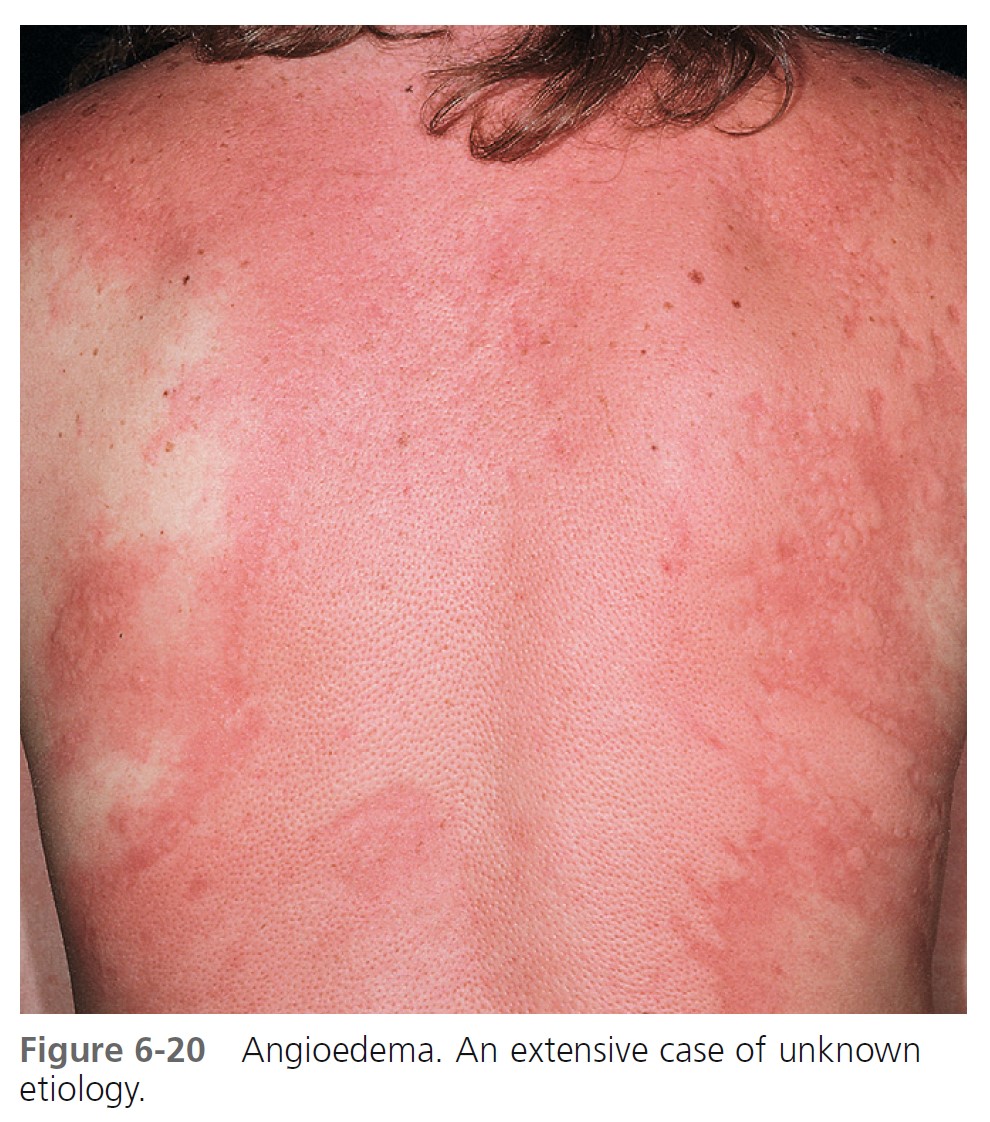

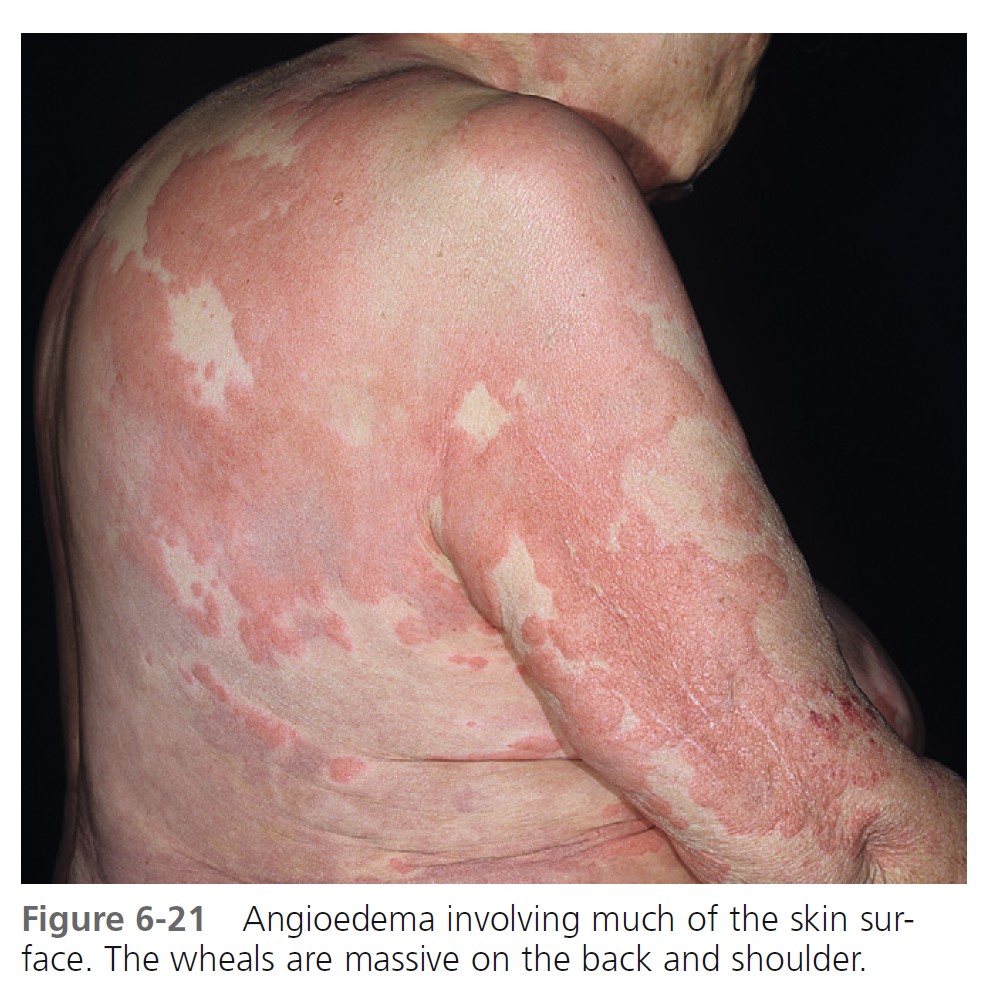

Angioedema (angioneurotic edema) is a hive like swelling caused by increased vascular permeability in the subcutaneous tissue of the skin and mucosa and the submucosal layers of the respiratory and GI tracts. A similar reaction occurs in the dermis with hives. Hives and angioedema commonly occur simultaneously and can have the same etiology. All types are listed in Box 6-9 and Table 6-3 . The presence of hives is characteristic of several types of angioedema. Absence of hives is characteristic of another group ( Box 6-10 ).

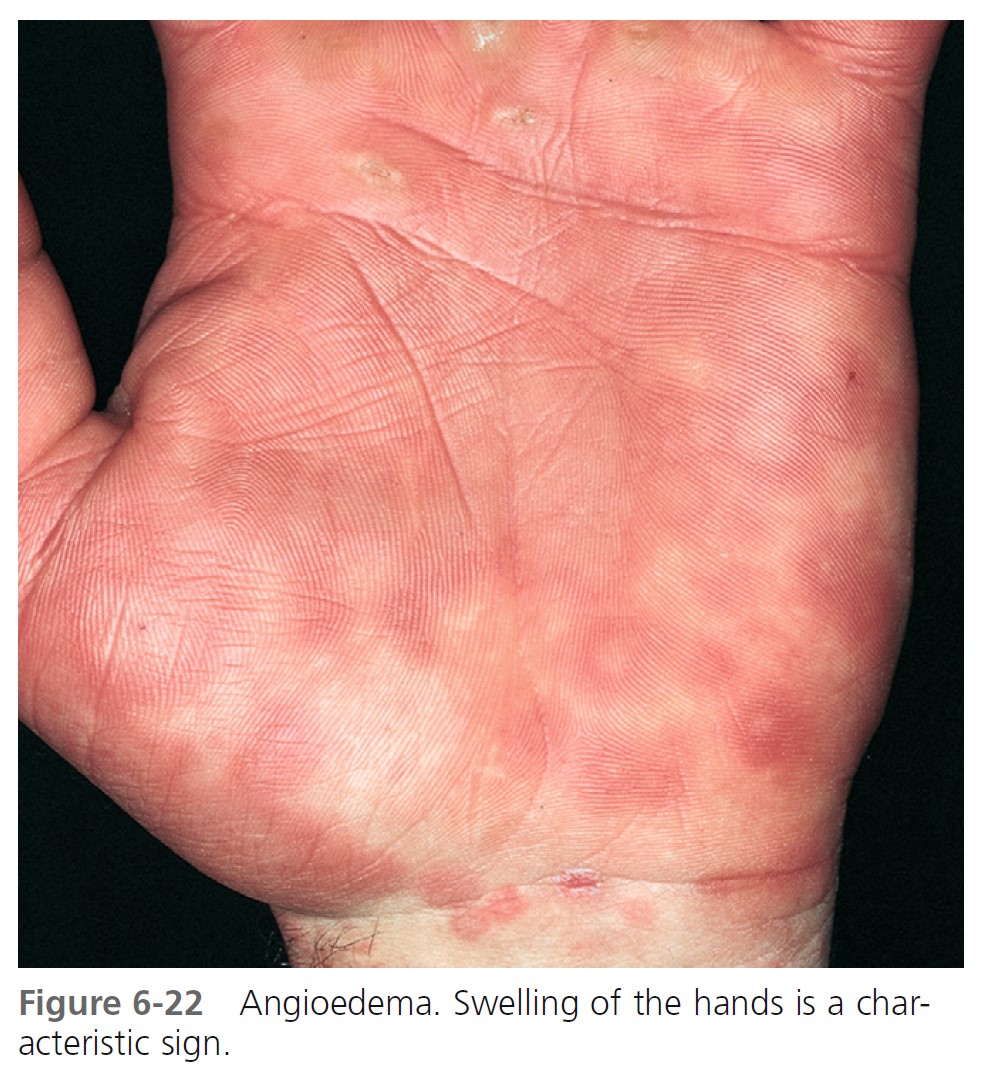

CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS. The deeper reaction produces a more diffuse swelling than is seen in hives. Itching is usually absent. Symptoms consist of burning and painful swelling. The lips, palms, soles, limbs, trunk, and genitalia are most commonly affected. Involvement of the GI and respiratory tracts produces dysphagia, dyspnea, colicky abdominal pain, and attacks of vomiting and diarrhea. GI symptoms are more common in the hereditary types of angioedema. Angioedema may occur as a result of trauma. Urticaria is rarely seen in hereditary or acquired angioedema.

In 1 report of 17 patients admitted during a 5-year period, 94% had angioedema in the head and neck (3 required urgent tracheotomy or intubation), 35% had recent initiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) therapy for hypertension, and 6% demonstrated classic hereditary angioedema. The majority (59%) had unclear etiologies for their symptoms.

Acquired forms of angioedema

IDIOPATHIC ANGIOEDEMA. Most cases of angioedema are idiopathic. Angioedema can occur at any age but is most common in the 40- to 50-year-old age group. Women are most frequently affected. The pattern of recurrence is unpredictable, and episodes can occur for 5 or more years. Involvement of the GI and respiratory tracts occurs, but asphyxiation is not a danger. A daily antihistamine is the initial prophylactic therapy.

Glucocorticoids are effective but the risks of chronic therapy usually outweigh the benefits. Long-term suppression may be needed. Alternate-day therapy is indicated if long-term suppression is required (e.g., prednisone 20 mg every other day), using the lowest dosage of prednisone required to provide adequate control.

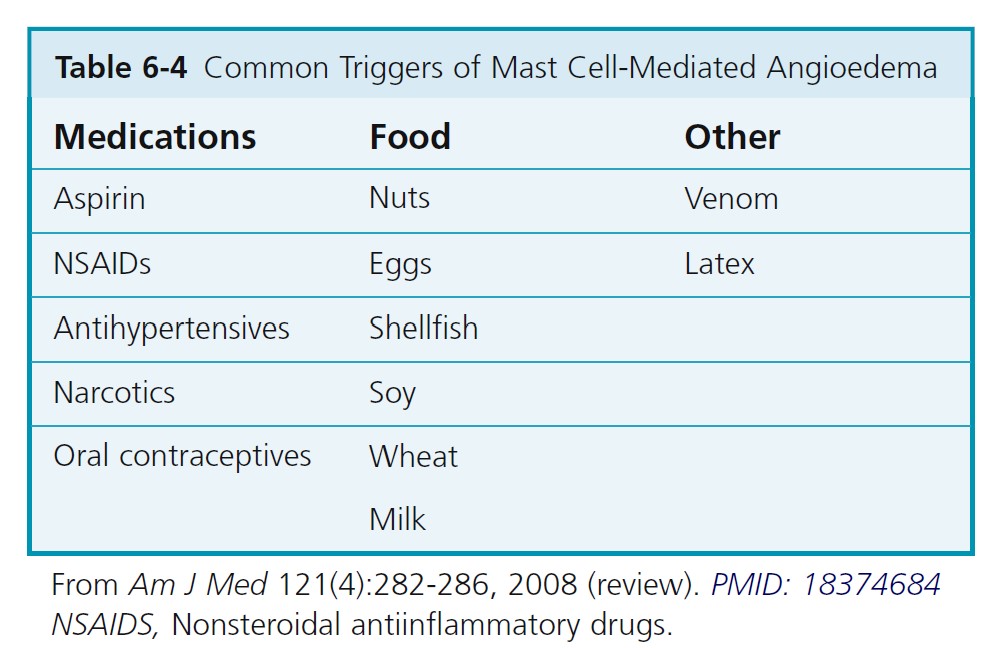

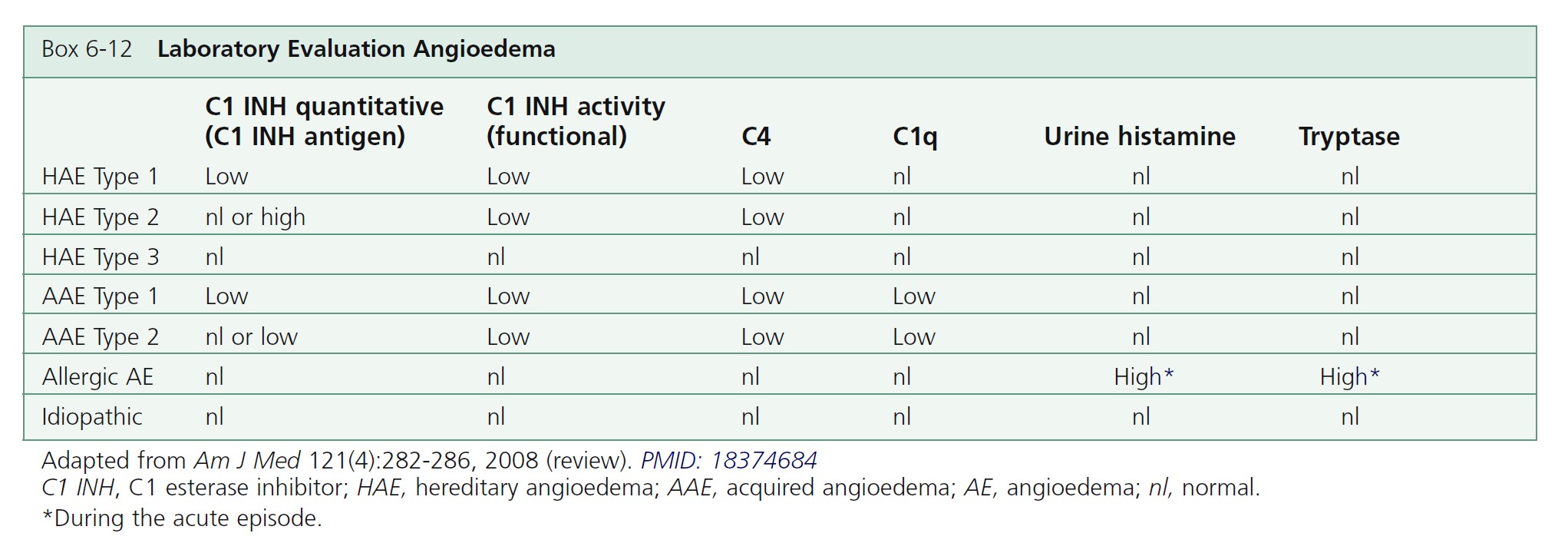

ALLERGIC OR IMMUNOGLOBIN E–MEDIATED ANGIOEDEMA. Severe allergic type I immediate hypersensitivity IgE-mediated reactions can cause acute angioedema and urticaria ( Figures 6-19 through 6-24 and Table 6-3 . IgE antibody on the mast cell surface unites with antigen (food, drug, stinging insect venom, pollen) and precipitates an immediate and massive release of histamine and other mediators from mast cells. Angioedema occurs alone or with the other symptoms of systemic anaphylaxis (i.e., respiratory distress, hypotension). Some forms of cold urticaria are IgE mediated and occur initially as angioedema. Common triggers are listed in Table 6-4 . Allergen avoidance is required. Above-normal levels of plasma tryptase and histamine in plasma and urine occur after allergen challenge in patients with immediate hypersensitivity. Order a serum tryptase and a 24-hour urine collection for histamine (see Box 6-12 ).

Antihistamines and glucocorticoids improve symptoms during an acute episode. Laryngeal edema responds well to epinephrine, which can be given intramuscularly or via an endotracheal tube. Daily antihistamines may decrease the severity of symptoms but often fail to prevent attacks.

MEDICATION- AND CHEMICAL-INDUCED ANGIOEDEMA. Contrast dyes used in radiology and drugs may also cause acute angioedema as a result of nonimmunologic mechanisms. Examples include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, such as aspirin and indomethacin, and ACE-inhibiting drugs.

Prescribe EpiPen or EpiPen Jr for patients who experience severe reactions with insect stings. The epinephrine in EpiPen is packaged in an auto-injector to avoid manual needle insertion.

Advise affected patients to wear a bracelet that identifies the diagnosis; their reactions could be misdiagnosed as symptoms related to alcoholism, stroke, myocardial infarction, or a foreign body in the airway.

ANGIOEDEMA FROM ANGIOTENSIN-CONVERTING ENZYME INHIBITORS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) are widely used for the treatment of mild forms of hypertension. They are the number one cause of acute angioedema in some hospitals. Angioedema occurs in 0.1% to 2.2% of patients receiving an ACE inhibitor and it is a potentially life-threatening adverse effect. The incidence may be higher in black Americans.

The onset usually occurs within hours to 1 week after starting therapy. Angioedema may occur suddenly even though the drug has been well tolerated for months or years; symptoms may regress spontaneously while the patient continues the medication, erroneously prompting an alternative diagnosis. ACE inhibitors seem to facilitate angioedema in predisposed subjects, rather than causing it

with an allergic or idiosyncratic mechanism.

Most cases from the short-acting ACEI captopril present with mild angioedema that can be controlled with antihistamines and glucocorticosteroids. In contrast, the angioedema induced by the long-acting ACE inhibitors lisinopril and enalapril has been serious.

The pathology has a special predilection for the tongue, a circumstance that renders orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation difficult; symptoms may progress rapidly despite aggressive medical therapy, necessitating emergency airway procedures. Individuals with a history of idiopathic angioedema probably should not be given ACE inhibitors. C1 inhibitor levels are usually normal.

Treatment includes immediate withdrawal of the ACE inhibitor and acute symptomatic supportive therapy. Angioedema that results from ACEIs is probably not IgE mediated, and antihistamines and steroids may not alleviate the airway obstruction. Alternative therapy with other classes of drugs to manage hypertension and/or heart failure must be chosen. Angiotensin II receptor antagonists have a lower incidence of adverse effects than ACE inhibitors as they do not produce cough and appear much less likely to produce angioedema.

Continuing use of ACE inhibitors, in spite of angioedema, results in a markedly increased rate of angioedema recurrence with serious morbidity.

ACQUIRED ANGIOEDEMA (C1 INH DEFICIENCY SYNDROMES)

Acquired angioedema (AAE) results from an acquired C1 INH deficiency. Acquired angioedema (AAE) is a rare disease that occurs in two forms: AAE-I and AAE-II. The two types are thought to be autoimmune (see Box 6-9 ). Type I is associated with lymphoproliferative diseases, including monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance and high-grade lymphomas, and occurs via consumption of the C1 INH protein by malignant cells. Type II is thought to be caused by the autoantibody to the C1 INH protein. AAE usually presents after the fourth decade of life. The laboratory characteristics of these two rare diseases are shown in Table 6-3 . C4, C1q, and C1 INH levels are low. Search for lympho proliferative disease and other neoplasms. Order serum protein electrophoresis, immunophoresis, peripheral blood lymphocyte immunophenotyping, and CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Initial studies may be negative. Angioedema can precede internal disease by up to 7 years.

Acute attacks are treated with epinephrine and glucocorticoids. High dosages of antihistamines may be effective. C1 INH concentrate and fresh-frozen plasma are the treatments of choice for acute episodes of AAE. These are less efficacious in AAE than in hereditary angioedema (HAE) because of the presence of autoantibody to the protein. Treatment of underlying lymphoproliferative disease is often curative in AAE-I. AAE-II has been treated with immunosuppressives. Androgens such as danazol are useful for frequent attacks.

EPISODIC ANGIOEDEMA-EOSINOPHILIA SYNDROME. This rare, non–life-threatening benign syndrome (also known as cytokine-associated AE syndrome or Gleich’s syndrome) consists of periodic attacks of angioedema, urticaria, pruritus, myalgia, oliguria, and fever. During attacks, body weights increase up to 18%, and leukocyte counts reach as high as 108,000/µl (88% eosinophils). Eosinophilia can persist between attacks. Attacks of angioedema last for about 6 to 10 days. Attacks resolve spontaneously or require short courses of corticosteroids to control symptoms and normalize the blood count. There is an increased level of the cytokines granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-5, and IL-6, which implicate CD4+ T lymphocytes in the pathophysiology of this process.

Hereditary angioedema

Hereditary angioedema results from a lack of functional C1 esterase inhibitor. Hereditary angioedema (inherited C1 inhibitor defi ciency) is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait and is due to mutations in the C1 inhibitor (C1 INH) gene. There are two types: type I (85% of cases) and type II (15% of cases). The clinical presentation for both types is the same. Type I is the most common and is characterized by an insufficient production of C1 inhibitor. This affects 85% of all patients with hereditary angioedema. Patients with type 2 have normal or elevated concentrations of C1 inhibitor but the protein is functionally deficient. The disease affects between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 50,000 persons. In most cases the disease begins in late childhood or early adolescence. Spontaneous occurrences are seen in up to 25% of patients. Many have ancestors who died suddenly from asphyxia. In the past, the mortality rate for attacks involving the upper airways exceeded 25%. Patients live in constant dread of life-threatening laryngeal obstruction.

Persons with hereditary angioedema have one normal and one abnormal C1 inhibitor gene. Under normal circumstances, this defect is clinically silent. Minor trauma, mental stress, and other unknown triggering factors lead to the release of vasoactive peptides that produce episodic swelling. Histamine has no role in this type of edema.

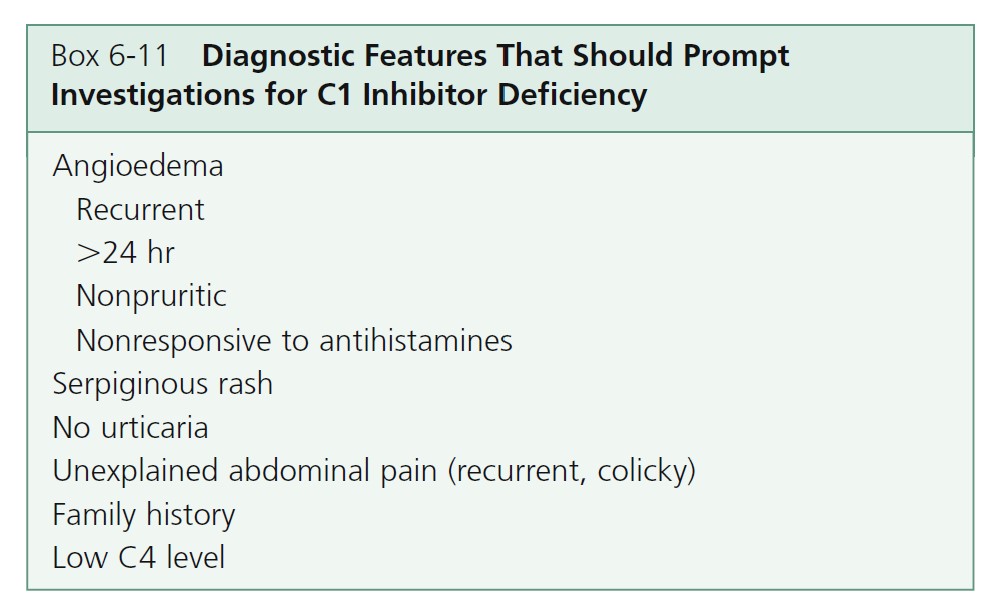

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS. Hereditary angioedema of the abdomen or oropharynx can result in death. Attacks may be complicated by incapacitating cutaneous swelling, life-threatening upper airway impediment, and severe GI colic. Patients usually experience attacks by the second decade of life. Delays in diagnosis are common. The diagnosis should be suspected in any patient who presents with recurrent angioedema or abdominal pain in the absence of urticaria. Symptoms begin in childhood, worsen at puberty, and persist throughout life ( Box 6-11 ). There are recurrent episodes of subcutaneous or submucosal edema. Minor trauma and stress frequently precipitate attacks.

Angioedema occurs at the following three sites: subcutaneous tissues (face, hands, arms, legs, genitalia, and buttocks); abdominal organs (stomach, intestines, bladder); and the upper airway, which may result in life-threatening laryngeal edema. The extremities are the cutaneous site most commonly reported. Swelling involves the extremities (96%), face (85%), oropharynx (64%), and intestinal

mucosa (88%).

SUBCUTANEOUS TISSUES. The swellings are not erythematous, pruritic, or painful. There are no hives. A tingling sensation precedes an attack. Swelling progresses for the first 24 hours and subsides in the next 2 or 3 days. Attacks occur about every 7 to 14 days but may be as often as every 3 days or as infrequent as years apart. Subcutaneous swellings resolve in 1 to 5 days.

ABDOMINAL ORGANS. Swelling of the gastrointestinal mucosa results in nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and severe pain that can mimic a surgical emergency. Diminished bowel sounds, guarding and rebound tenderness may be misinterpreted and lead to unnecessary abdominal surgery. Abdominal symptoms resolve within 12 to 24 hours.

UPPER AIRWAY. Obstruction of the upper respiratory tract is responsible for the 30% mortality rate.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS OF HAE. The diagnosis is suggested by the family and personal history. A laboratory workup confirms the diagnosis (see Box 6-12 and Table 6-3 ). All patients with hereditary angioedema have a persistently low antigenic C4 level with normal antigenic C1 and C3 levels. Measure C4 levels as a screening test. In rare cases, the C4 level is normal between attacks. If C4 levels are low, then measure antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels. This confirms the diagnosis of hereditary angioedema and distinguishes between HAE type I (low antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels) and HAE type II (normal antigenic C1 inhibitor level but low functional C1 inhibitor activity). A rare third type (HAE type III) of familial angioedema has been described; in type III HAE, patients have normal antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels.

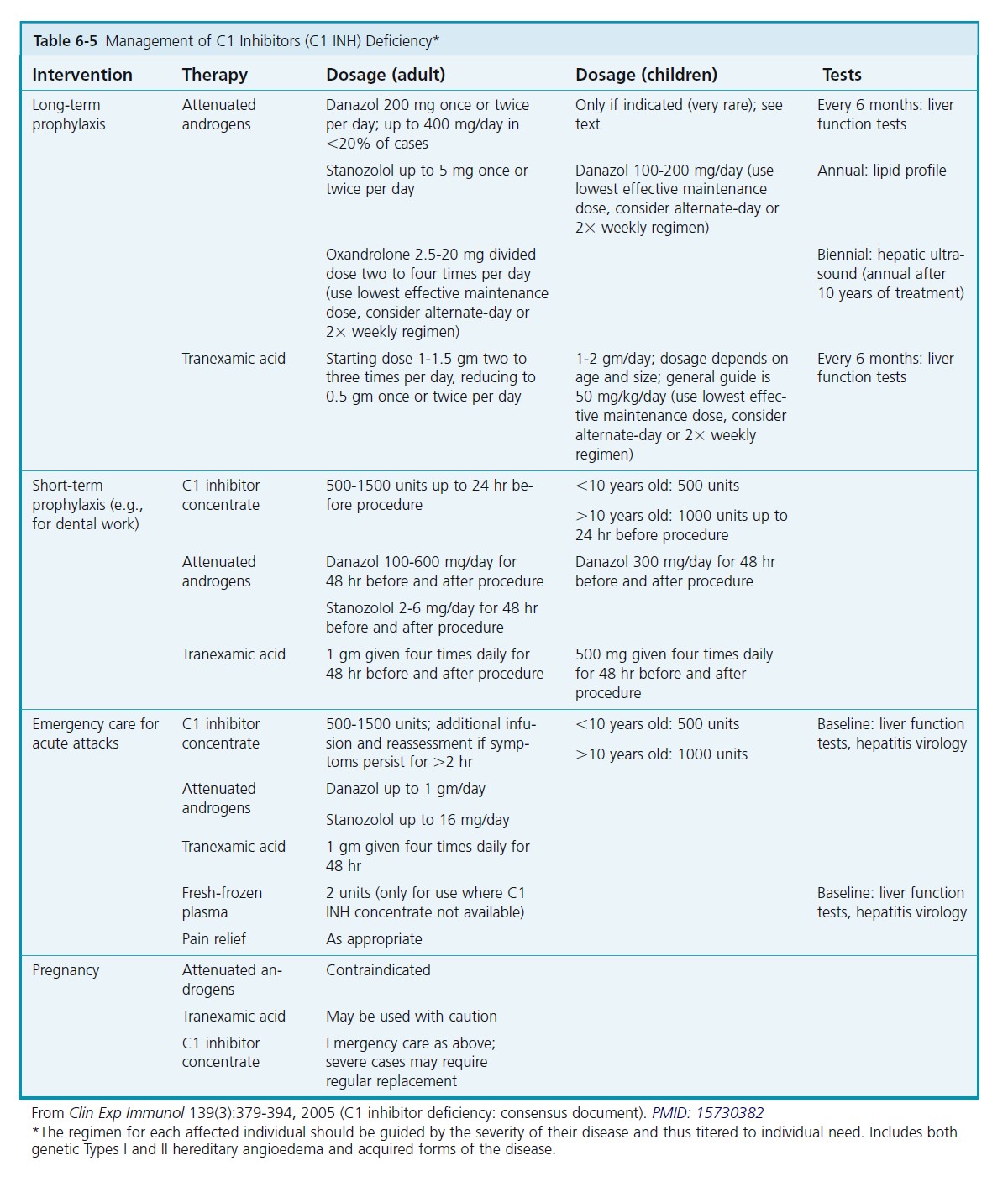

TREATMENT OF HAE. The treatment of C1 inhibitor deficiency is summarized in Table 6-5 . Antihistamines, corticosteroids, and adrenergic drugs are of little value. Treatment is graded according to response and the clinical site of swelling. Acute treatment for severe attack is by infusion of C1 inhibitor concentrate and for minor attack attenuated androgens and/or tranexamic acid. Prophylactic treatment is by attenuated androgens and/or tranexamic acid. There are a number of new products in trials.

CONTACT URTICARIA SYNDROME

Contact of the skin with various compounds can elicit a wheal-and-flare response. Most patients give a history of relapsing dermatitis or generalized urticarial attacks rather than a localized hive; others complain only of localized sensations of itching, burning, and tingling. This is in contrast to allergic contact dermatitis, which is an eczematous reaction caused by cell-mediated immunity.

Contact urticaria is characterized by a wheal and flare that occur within 30 to 60 minutes after cutaneous exposure to certain agents. Direct contact of the skin with these agents may cause a wheal-and-flare response restricted to the area of contact, generalized urticaria, urticaria and asthma, or urticaria combined with an anaphylactoid reaction. There are nonimmunologic and immunologic forms.

NONIMMUNOLOGIC CONTACT URTICARIA. The nonimmunologic type is the most common and most benign. This form does not require prior sensitization. Nonimmunologic, histamine-releasing substances are produced by certain plants (nettles), animals (caterpillars, jellyfish), and medications (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]). Anaphylaxis may occur after application of bacitracin ointment. Other implicated substances include cobalt chloride, benzoic acid, cinnamic aldehyde, cinnamic acid, and sorbic acid.

IMMUNOLOGIC CONTACT URTICARIA. Immunologic contact urticaria is due to an IgE immediate hypersensitivity reaction. Some patients experience rhinitis, laryngeal edema, and abdominal disturbances. Latex rubber, bacitracin, potato, apple, mechlorethamine, and henna have been implicated.

OTHER PRECIPITATING FACTORS. The mechanism by which wood, plants, foods, cosmetics, and animal hair and dander cause contact urticaria has not been defined. The term protein contact dermatitis is used when an immediate reaction occurs after eczematous skin is exposed to certain types of food (fish, garlic, onion, chives, cucumber, parsley, tomato), animal dander (cow hair and dander), or plant substances. Cooks who complain of burning or stinging when handling certain foods may have contact urticaria syndrome.

DIAGNOSIS. Because there is no standard test battery for routine evaluation of contact urticaria, a careful history concerning the occurrence of immediate reactions, whether localized or generalized, is essential. An open patch test may be performed by applying a drop of the suspected substance to the ventral forearm and observing the site for a wheal 30 to 60 minutes later. Closed tests may be associated with more intense or generalized reactions.

Prick testing (using fresh samples of the food suspected from the patient’s history) is an accurate method of investigation for selected cases of hand dermatitis in patients who spend considerable time handling foods (e.g., catering workers, cooks). Seafood is a common allergen. A radioallergosorbent test (RAST) can confirm immunologic contact urticaria.

PRURITIC URTICARIAL PAPULES AND PLAQUES OF PREGNANCY

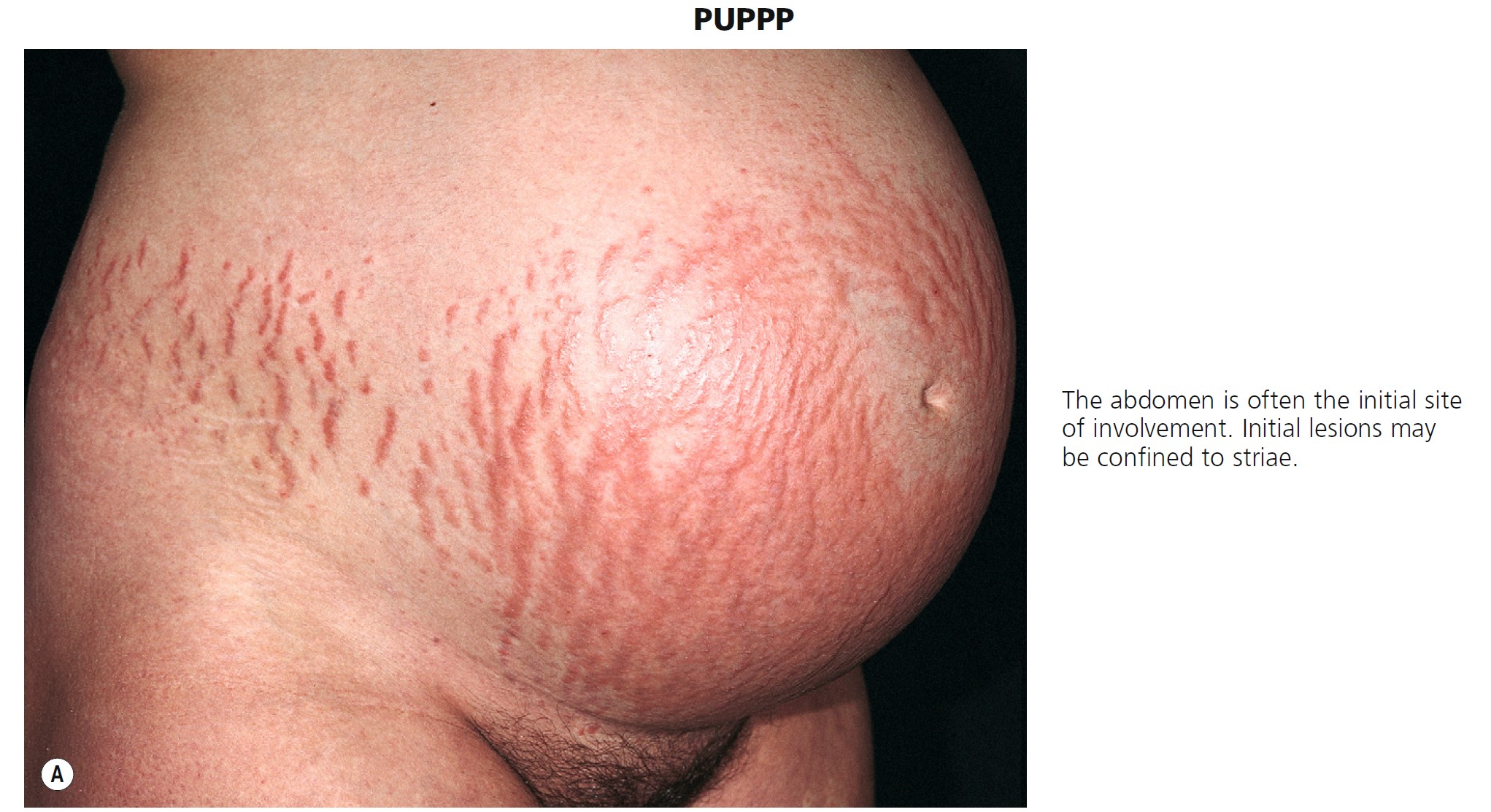

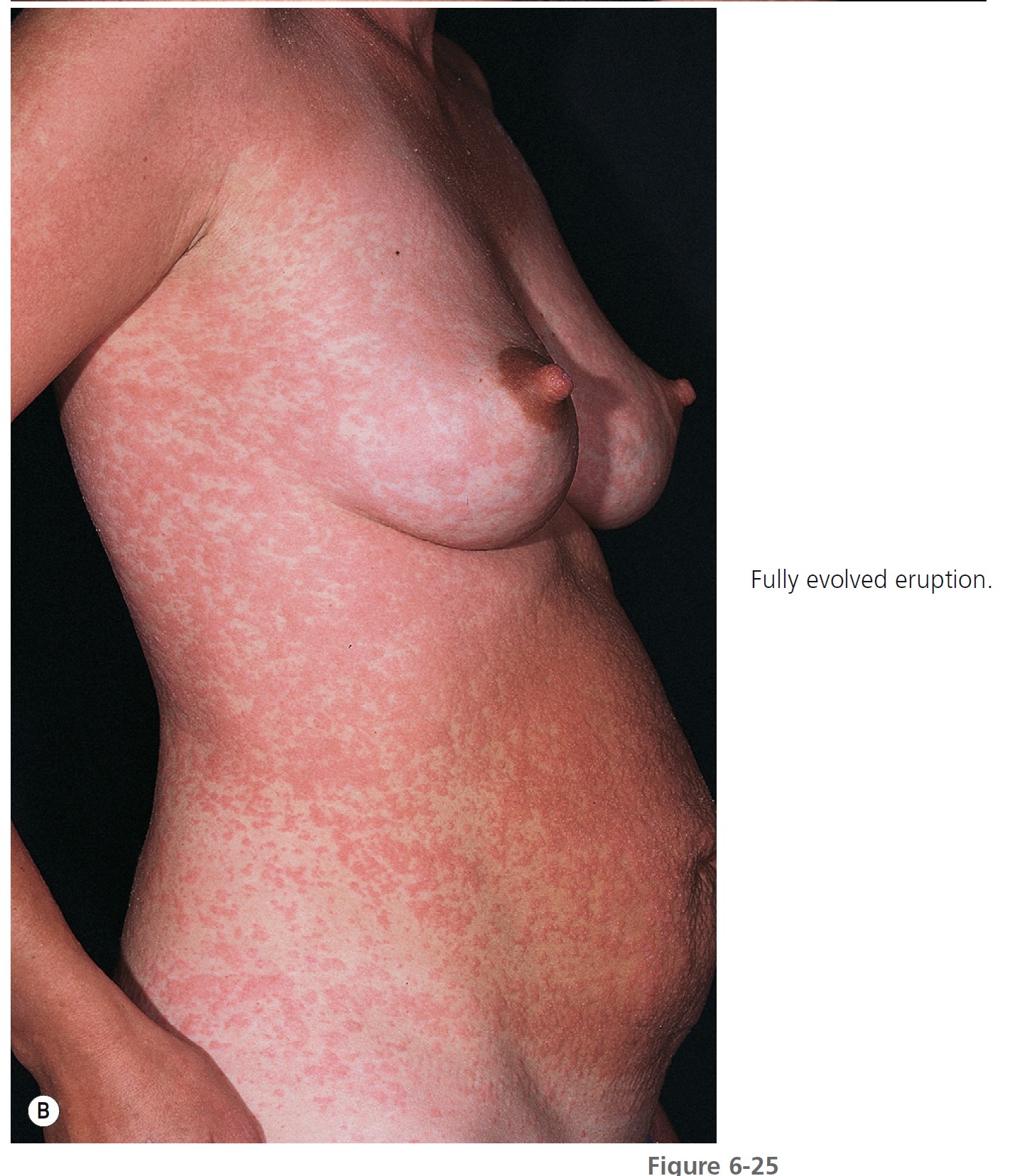

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), or polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, is the most common gestational dermatosis, affecting between 1 in 130 and 1 in 300 pregnancies. It is seen most frequently in primigravidas and begins late in the third trimester of pregnancy (mean onset, 35 weeks) or occasionally in the early postpartum period. The eruption appears suddenly, begins on the abdomen in 90% of patients ( Figure 6-25 , A ), and in a few days may spread in a symmetric fashion to involve the buttocks, proximal arms, and backs of the hands ( Figure 6-25 , B ). The initial lesions may be confined to striae. The face is not involved. Itching is moderate to intense, but excoriations are rarely seen. The lesions begin as red papules that are often surrounded by a narrow, pale halo. They increase in number and may become confluent, forming edematous urticarial plaques or erythema multiforme–like target lesions that may look like the lesions of herpes gestationis. In other patients, the involved sites acquire broad areas of erythema, and the papules remain discrete. Papulovesicles have been reported. The mean duration is 6 weeks, but the rash is usually not severe for more than 1 week. Unlike urticaria, the eruption remains fixed and increases in intensity, clearing in most cases before or within 1 week after delivery. Recurrence with future pregnancies is unusual. There have been no fetal or maternal complications. Infants do not develop the eruption. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy are significantly associated with multiple pregnancies, hypertensive disorders, and induction of labor. Perinatal outcome is comparable to that of pregnancies without PUPPP. PMID: 16753771 It was postulated that abdominal distention or a reaction to it may play a role in the development of PUPPP.

The biopsy reveals a nonspecific perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. Eosinophils have also been noted in most biopsies. There are no laboratory abnormalities, and direct immunofl uorescence of lesional and perilesional skin is negative.

Treatment is supportive. The expectant mother can be assured that pruritus will quickly terminate before or after delivery. Itching can be relieved with group V topical steroids; cool, wet compresses; oatmeal baths; and antihistamines. Antipruritic topical medications (menthol, doxepin) are useful. Prednisone (40 mg/day) may be required if pruritus becomes intolerable. Several patients were treated successfully with UVB therapy.

URTICARIAL VASCULITIS

Urticarial vasculitis (UV) is a subset of vasculitis characterized clinically by urticarial skin lesions and histologically by necrotizing vasculitis.

Immune complexes are thought to lodge in small blood vessels with activation of complement, mast cell degranulation, infiltration by acute inflammatory cells, fibrin deposition, and blood vessel damage.

There is a spectrum of clinical and laboratory features. Many patients have minimal signs or symptoms of systemic disease. Systemic symptoms include angioedema (42%), arthralgias (49%), pulmonary disease (21%), and abdominal pain (17%). Thirty-two percent have hypocomplementemia, 64% have lesions that last more than 24 hours, 32% have painful or burning lesions, and 35% have lesions that resolve with purpura or hyperpigmentation.

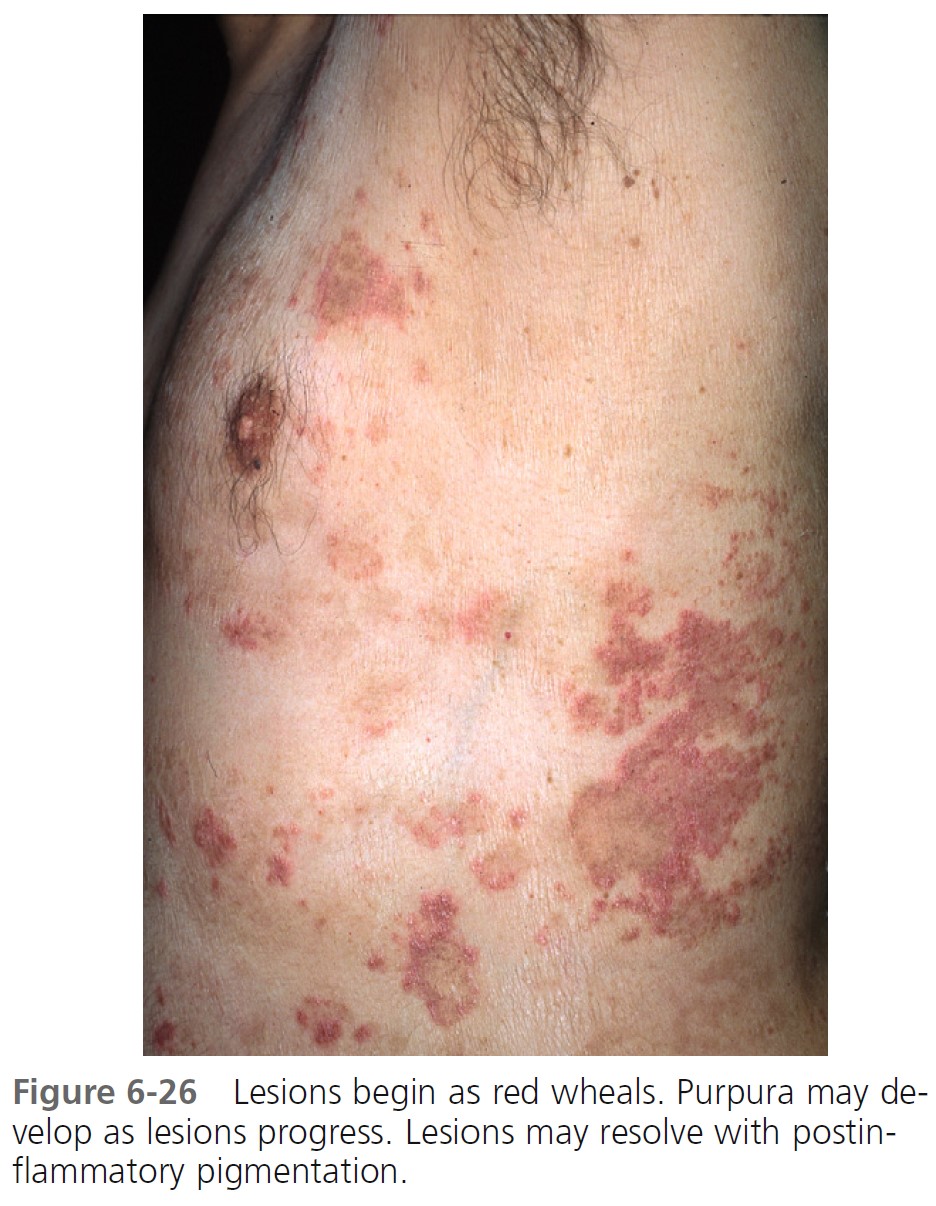

CLINICAL FEATURES. Overall, patients with urticarial vasculitis tend to have a benign course. Urticarial plaques in most patients with typical chronic urticaria resolve completely in less than 24 hours and disappear while new plaques appear in other areas. Urticarial vasculitis plaques persist for 1 to 7 days and may have residual changes of purpura, scaling, and hyperpigmentation ( Figures 6-26 and 6-27 ). However, in one study wheals lasted less than 24 hours in 57.4% of patients, and pain or tenderness was reported by 8.6%. Extracutaneous features were present in 81%, hypocomplementemia in 11%, and abnormalities of other laboratory parameters (e.g., raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, microscopic hematuria) in 76.6%. The lesions are burning and painful rather than itchy. Patients with urticarial vasculitis have been categorized into two subgroups: those with hypocomplementemia and those with normal complement levels.

NORMOCOMPLEMENT UV. Normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis is usually idiopathic. This most common form has also been described in patients with monoclonal gammopathy, neoplasia, repeated cold exposure, and ultraviolet light sensitivity.

HYPOCOMPLEMENT UV. Patients with hypocomplementemia are more likely to have systemic involvement than patients with normal complement levels. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis can present as or precede a syndrome that includes obstructive pulmonary disease and uveitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, or cryoglobulinemia (which is closely linked with hepatitis B or C virus infection).

LABORATORY TESTS. Order CBC, ESR, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, ANA, anti-DNA, anti-Sm, complement assay, anti-C1q antibodies, cryoglobulins, Schirmer’s test, and pulmonary function tests.

As with typical cutaneous vasculitis, most patients have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Anti-C1q autoantibody develops in disorders characterized by immune complex–mediated injury and appears in most patients with hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Patients with more severe involvement have hypocomplementemia (hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome) with depressed CH50, C1q, C4, or C2 levels.

BIOPSY. Biopsy shows a histologic picture that is indistinguishable from that seen in cutaneous necrotizing vasculitis (palpable purpura). Fragmentation of leukocytes and fibrinoid deposition occur in the walls of postcapillary venules, a pattern called leukocytoclastic vasculitis. There is an interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate of the dermis.

IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE. Patients with hypocomplementemia may have an immunofluorescent pattern of immunoglobulins or C3 as determined by routine direct immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence in patients with hypocomplementemia shows deposition of Ig and C3; 87% have fluorescence of the blood vessels, and 70% have fluorescence of the basement membrane zone. Rule out other diseases in which cutaneous vasculitis may present as a urticarial-like eruption (e.g., viral illness, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, and serum sickness).

TREATMENT. Prednisone in dosages exceeding 40 mg/day is effective. Other medications reported to be effective are indomethacin (25 mg three times daily to 50 mg four times daily), colchicine (0.6 mg two or three times daily), dapsone (up to 200 mg/day), low-dose oral methotrexate, and antimalarial drugs. Cinnarizine was effective in a high percentage of the patients. PMID: 18681869

SERUM SICKNESS

Serum sickness is a disease produced by exposure to drugs, monoclonal antibody therapy (rituximab), blood products, or animal-derived vaccines. After exposure to these antigens, a strong host-antibody response occurs. These circulating antibodies react with the newly introduced antigen to form precipitating antigen-antibody complexes. This is a type III (immune complex) reaction, or Arthus reaction. These circulating immune complexes are trapped in vessel walls of various organs, where they activate complement. A rise in the level of immune complexes is accompanied by a decrease in serum levels of C3 and C4 and an increase in C3a/C3a desarginine, a split product of C3 whose presence indicates that the complement system has been activated by immune complexes. Inflammatory mediators are released. C3a/C3a des-arginine, a potent anaphylotoxin, induces mast cell degranulation to produce hives.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS. Symptoms appear 8 to 13 days after exposure to the drug or antisera and last for 4 or more days. They include fever, malaise, skin eruptions, arthralgias, nausea, vomiting, occult blood in the stool, and lymphadenopathy. The disease resolves without sequelae in most cases. The skin eruption begins with the onset of other symptoms. A morbilliform rash or urticaria is limited to the trunk or may become generalized. The hands and feet may be involved.

DIAGNOSIS. The white blood count may be as high as 25,000/mm3 . Serum C3 and C4 levels are below normal. Proteinuria occurs in 40% of patients. Direct immunofluorescence of skin lesions less than 24 hours old shows Ig deposits (IgM, IgE, IgA, or C3) in the superficial small blood vessels. Drugs are now the most common cause of serum sickness. Penicillin, sulfa drugs, thiouracils, cholecystographic dyes, hydantoins, aminosalicylic acid, and streptomycin are most often implicated.

TREATMENT. The offending agent must be avoided. Antihistamines such as hydroxyzine control the hives. Prednisone 40 mg/day is used if symptoms are intense.

MASTOCYTOSIS

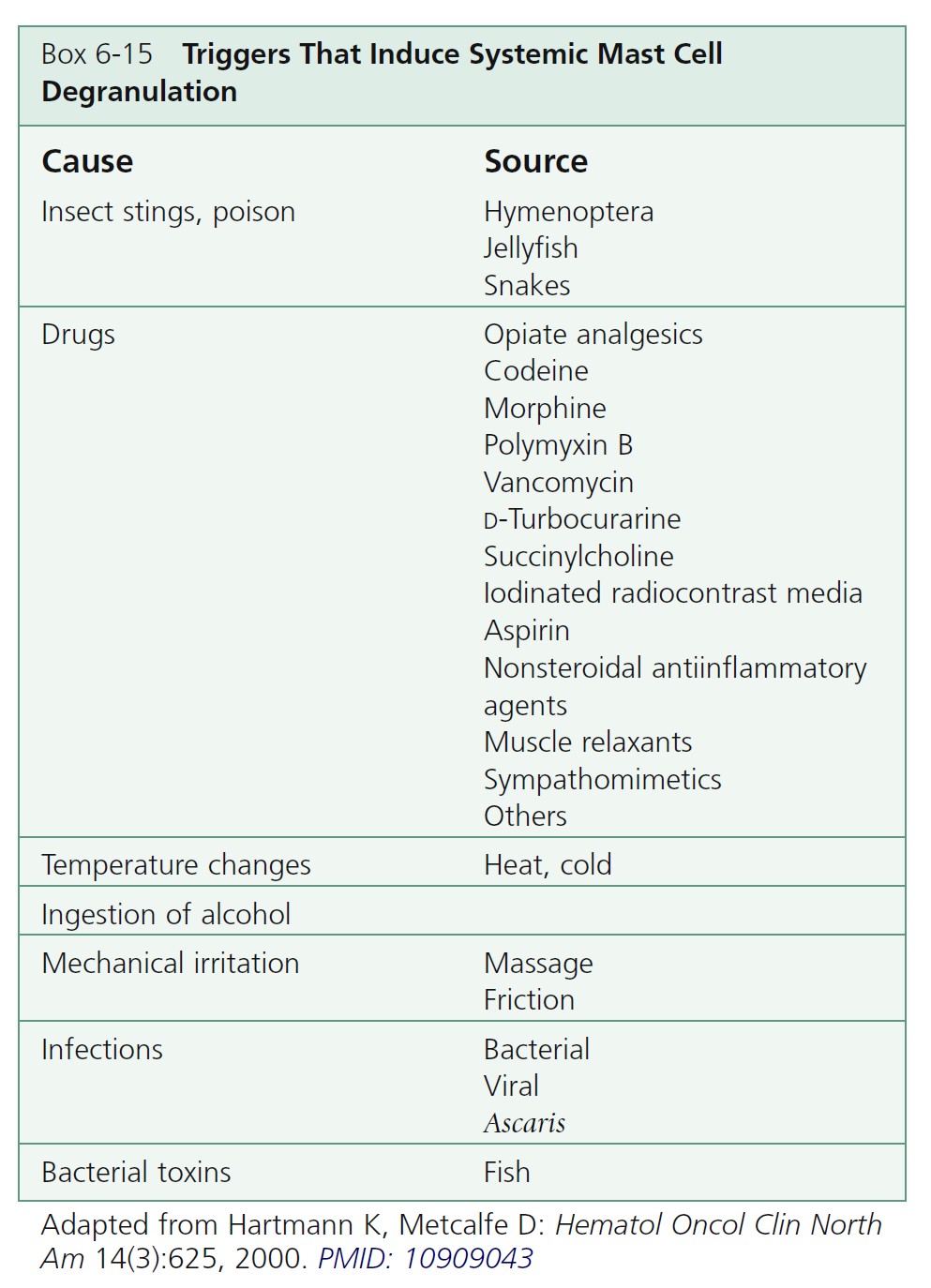

Mastocytosis is a group of rare diseases characterized by abnormal growth of mast cells in skin, bone marrow, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. Mast cells store histamine in granules. Histamine is released by scratching the lesions or ingesting certain agents. The most frequent site of organ involvement with all forms of mastocytosis is the skin. In young children, the disease is usually confined to the skin; in adults, mastocytosis is usually systemic. Signs and symptoms result from mast cell mediators and mast cell organ infiltration.

Mast cell degranulation causes episodic flushing, dyspepsia, diarrhea, abdominal pain, musculoskeletal pain, or hypotension.

Pathological examination showing mast cell infiltration confirms the diagnosis. Antihistamines and mast cell stabilizing agents such as sodium cromolyn provide symptomatic relief. Interferon, cladribine, and imatinib may be helpful. Aggressive disease is managed with chemotherapy or bone marrow transplantation. Familial occurrence is only rarely documented. The cause of mastocytosis is unknown.

Several genetic mutations are documented.

Spectrum of disease

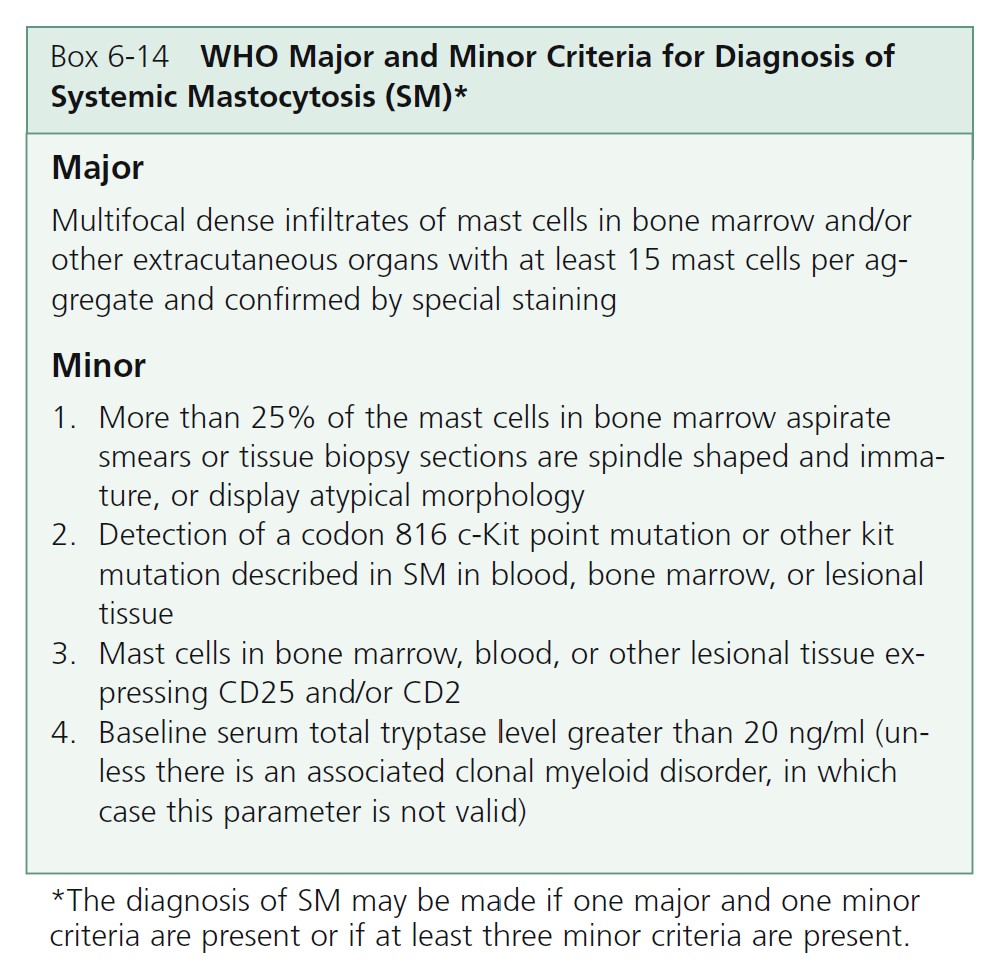

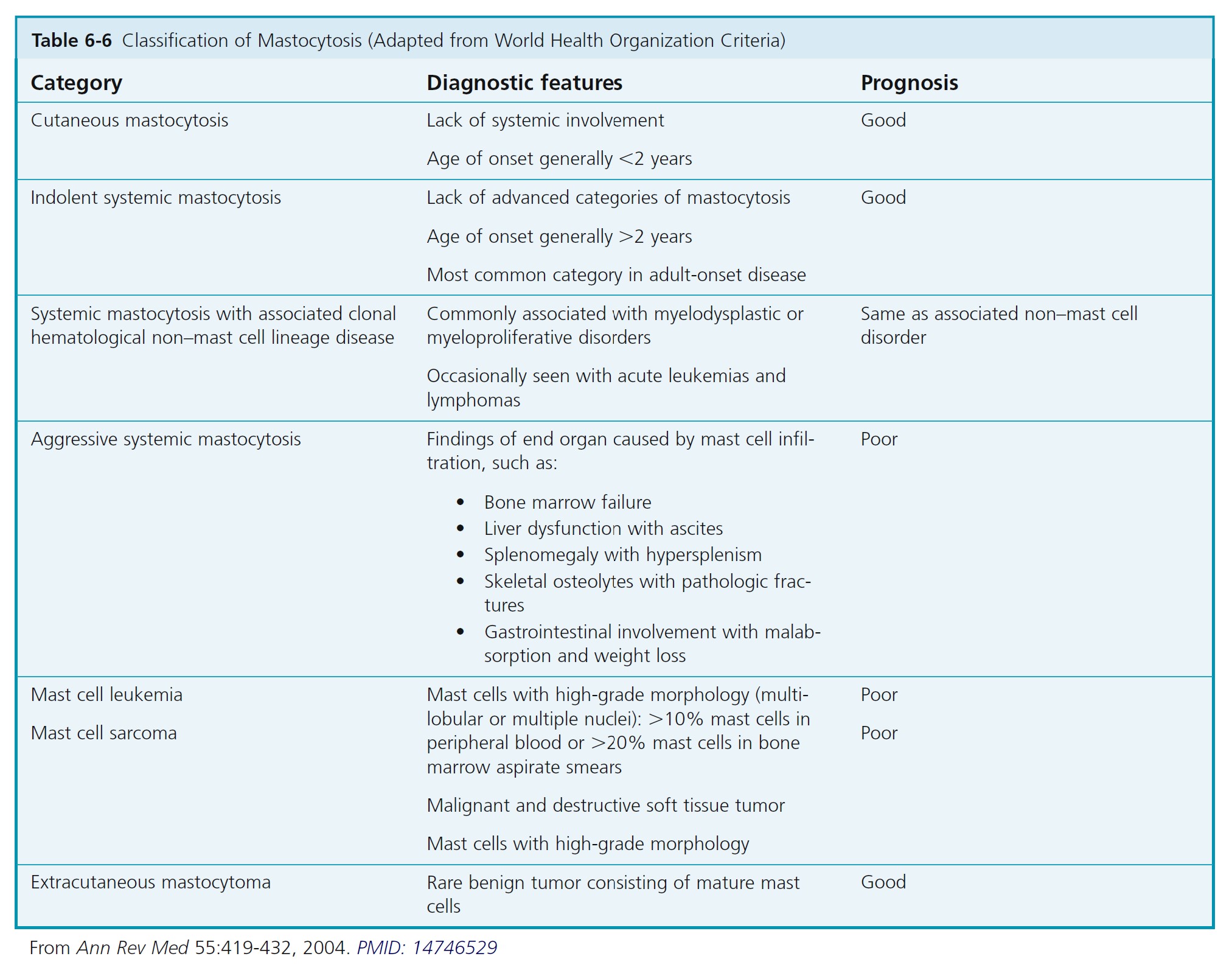

Mastocytosis comprises several diseases characterized by an abnormal increase in tissue mast cells. Cutaneous mastocytosis (CM) is the most common form of mastocytosis, affects predominantly children, and presents as a mast cell hyperplasia limited to the skin. Systemic mastocytosis (SM) comprises multiple distinct entities in which mast cells infiltrate the skin and/or other organs. The diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis is based on the presence of one major criterion and one minor criterion or three minor criteria.

CUTANEOUS MASTOCYTOSIS

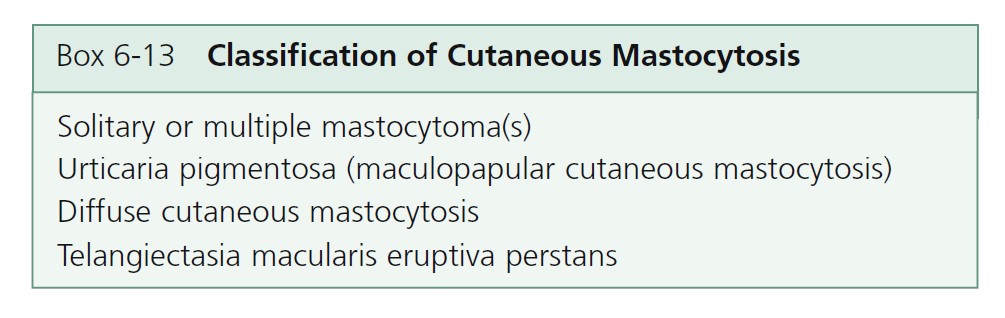

There are several types of skin mast cell disease. Most cases of pediatric mastocytosis are sporadic and appear during the first 2 years of life, especially on the trunk. Urticaria pigmentosa is the most frequent variant. The prognosis of pediatric mastocytosis is good. There are three main forms of CM defined by the WHO: urticaria pigmentosa (UP), also called maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis (MPCM); diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (DCM); and mastocytoma of the skin ( Box 6-13 ). A number of rare subvariants of UP have been described including telangiectelangiectasia macularis eruptive persistans (TMEP), a nodular and a plaque form.

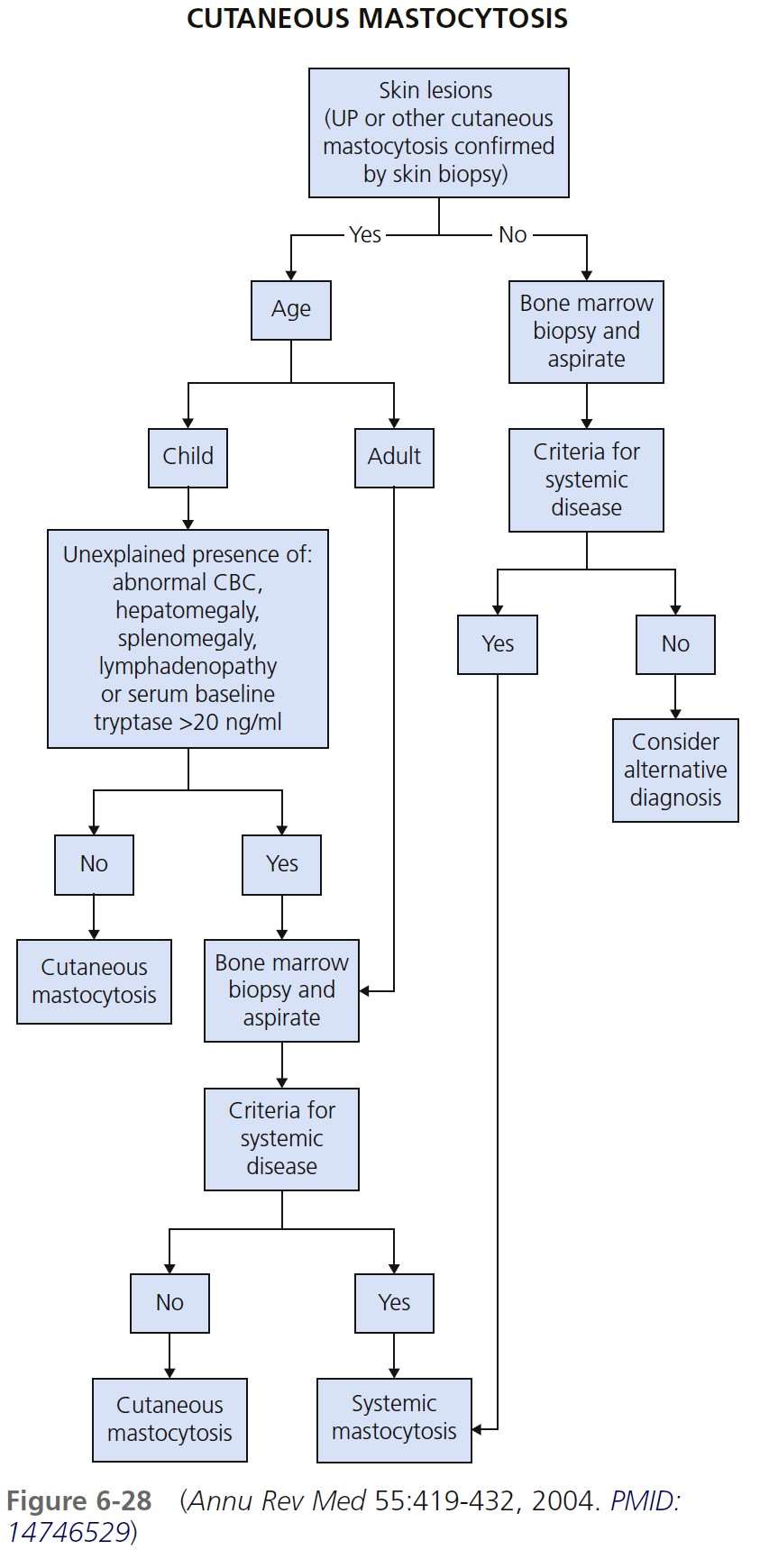

A clinical diagnosis is made by typical skin lesions and lack of systemic symptoms. Determine a baseline serum tryptase level. Skin biopsy shows mast cells in the dermis. Immunohistochemical staining with tryptase is more sensitive than metachromatic stains such as Giemsa or toluidine blue. Determine if the patient with cutaneous mastocytosis also has systemic mastocytosis. Figure 6-28 outlines one approach to this diagnostic evaluation. Cutaneous mastocytosis without systemic disease is common in pediatric-onset mastocytosis. Cutaneous mastocytosis is accompanied by systemic disease in most patients who have onset of lesions after age 2.

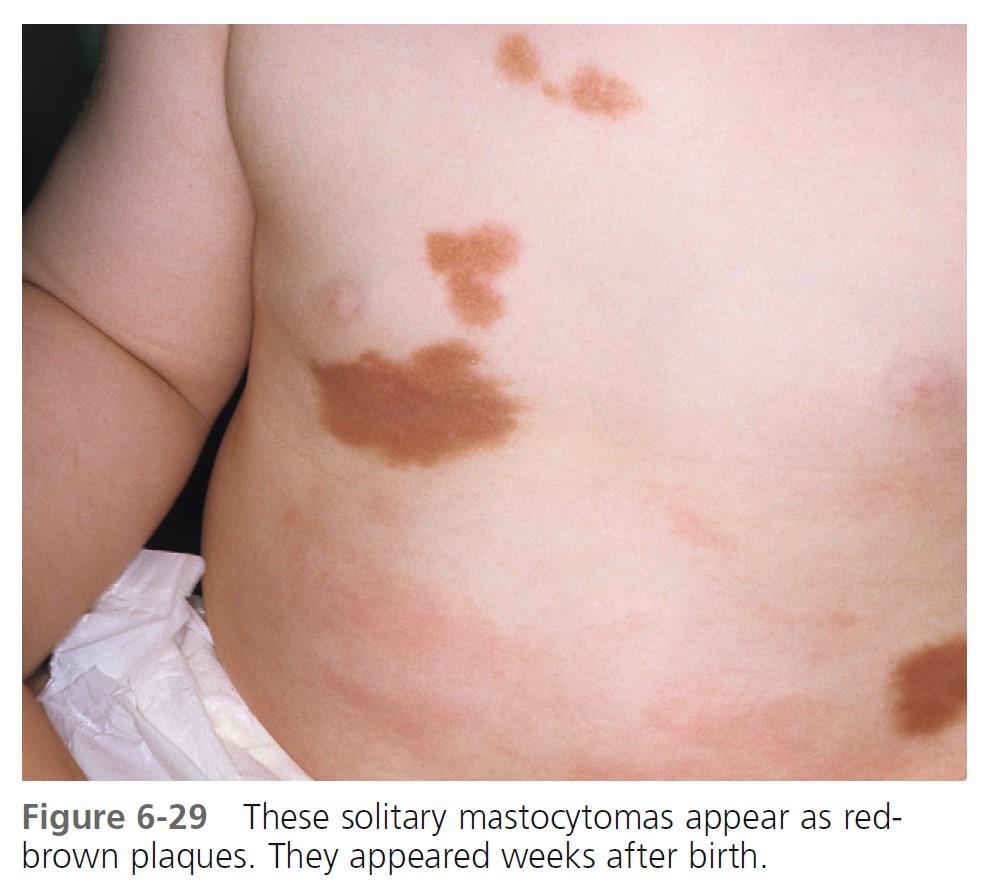

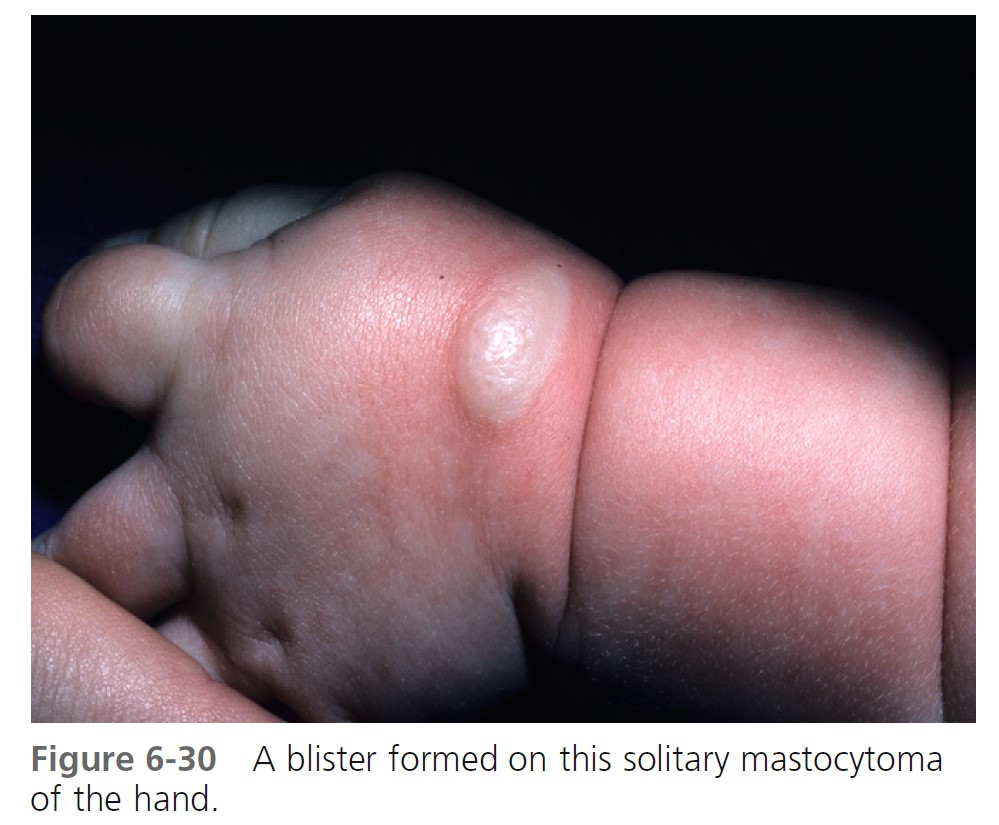

SOLITARY MASTOCYTOMA. A larger solitary collection of mast cells is called a mastocytoma ( Figures 6-29 and 6-30 ). Mastocytoma is the most common type of cutaneous mastocytosis. There are one or multiple lesions. They are reddish brown nodules or plaques that can be several centimeters in diameter. Stroking induces whealing (“Darier’s sign”). It is due to cutaneous mast cell degranulation and histamine release. The lesions either are present at birth or develop within a median time of 1 week; most appear within the first 3 months of life. They are rare in adults. Bullae may be seen. Children rarely develop additional mastocytomas more than 2 months after onset of the initial lesions. Most occur on the extremities but not the palms or soles. Lesions may spontaneously involute. If a lesion does not involute, it may be surgically removed. Transition to systemic involvement does not occur.

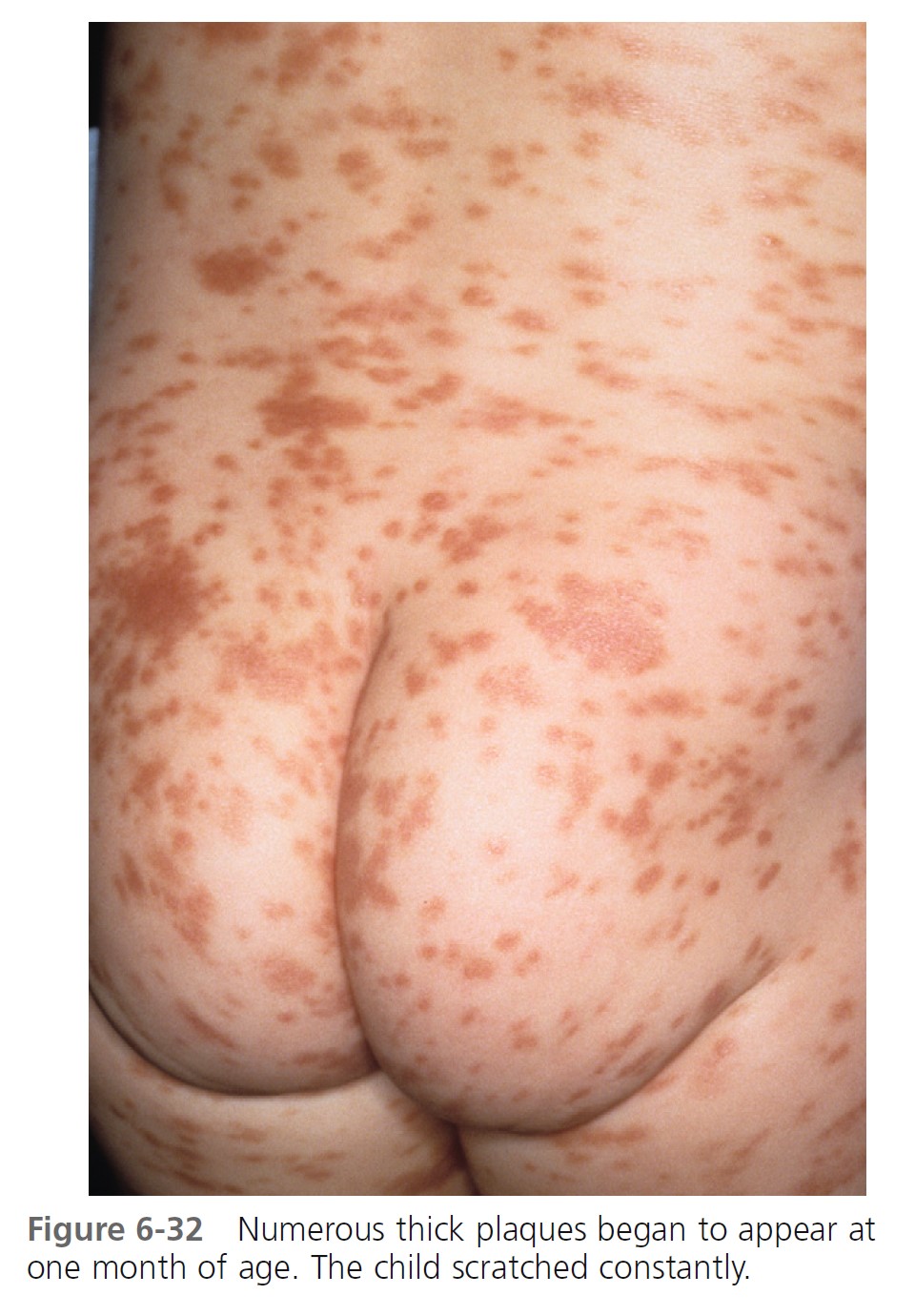

URTICARIA PIGMENTOSA. Urticaria pigmentosa is the second most frequent manifestation of mastocytosis in children. It may be present at birth, may appear in infancy and childhood at a median age of 2.5 months, and is present in 80% of affected individuals within 6 months. Cases gradually improve, and symptoms resolve in about 50% of patients by adolescence. Urticaria pigmentosa that begins after age 10 usually persists and may be associated with systemic disease. After the age of 10 years, the median time of onset for urticaria pigmentosa is 26.5 years. Lesions are well demarcated, red-brown, slightly elevated plaques averaging 0.5 to 1.5 cm in diameter. They occur in small groups on the trunk and are often dismissed as variations of pigmentation ( Figures 6-31 through 6-35 ). Large numbers can occur on any body surface. The palms and soles are spared. Mucous membranes may be involved. Lesions may increase in number for years. Infants may develop bullae and vesicles until the age of 2; bullae are rarely observed after age 2. Bullae heal without scarring. Pruritus, flushing, and dermatographism occur. Darier’s sign (the wheal-and-flare reaction that is seen following brisk stroking of the lesions) can be elicited (see Figures 6-31 and 6-34 ).

\

\

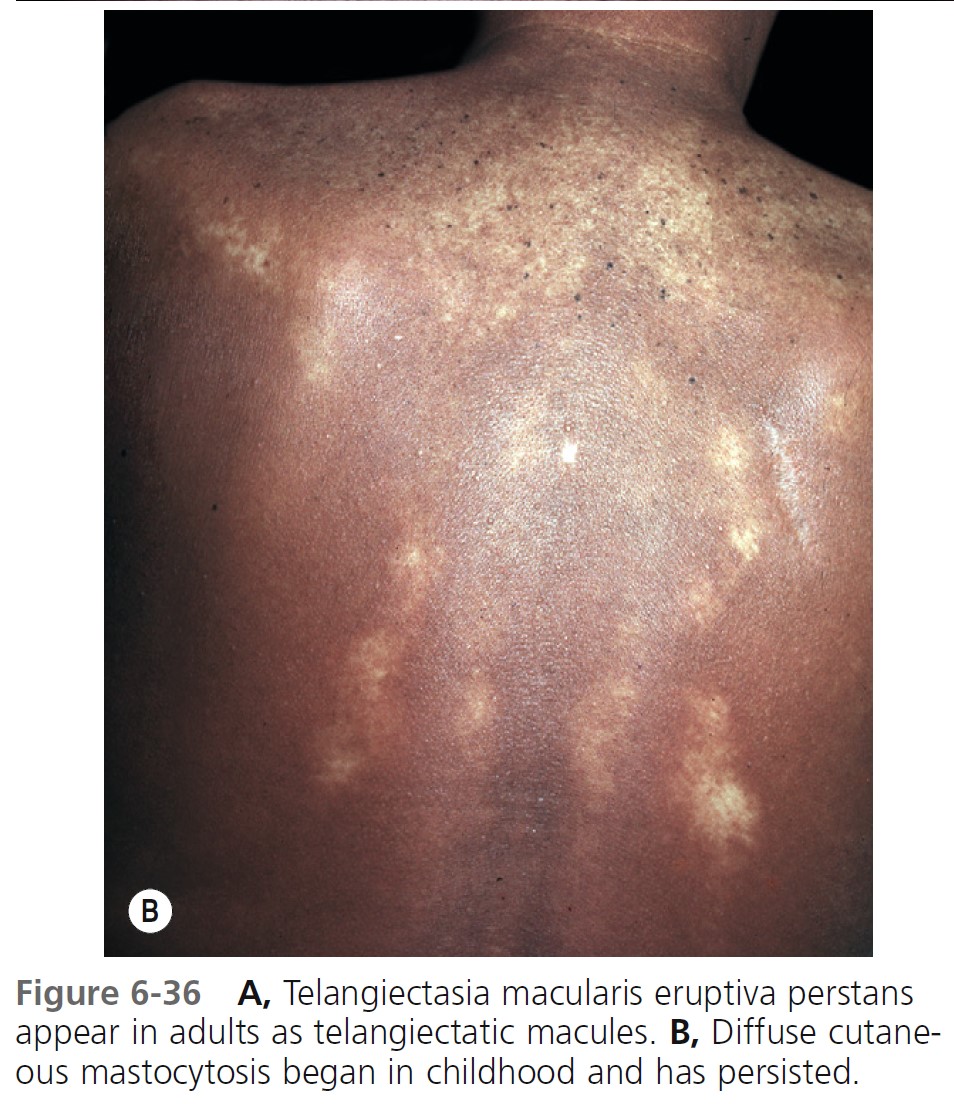

TELANGIECTASIA MACULARIS ERUPTIVA PERSTANS (TMEP). TMEP is the rarest cutaneous form. It is limited to adults and consists of telangiectasias and sparse, widespread mast cell infiltrates that resemble freckles. Pruritus, purpura, and blisters do not occur. The lesions are redbrown, telangiectatic macules with irregular borders. The biopsy in cases of TMEP reveals increased numbers of perivascular mast cells ( Figure 6-36 ).

DIFFUSE CUTANEOUS TYPES. There are two rare, generalized forms of cutaneous disease. Diffuse erythrodermic cutaneous mastocytosis appears either as normal skin or as thickened, reddish brown edematous skin with an orange peel texture. These pediatric patients have a diffuse infiltration of the entire skin by mast cells. It presents before the age of 3 years. These patients have the highest frequency of systemic mastocytosis. Dermographism with hemorrhagic blisters is common. Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis usually resolves spontaneously between the ages of 15 months and 5 years. Diffuse generalized infi ltration of the skin is called pseudoxanthomatous mastocytosis, or xanthelasmoidea and begins in childhood and persists throughout life.

SYSTEMIC MASTOCYTOSIS

Systemic mastocytosis can occur at any age but is generally seen in older children and adults. The frequency of skin lesions ranges from 50% to 100%. Systemic mast cell disease occurs in approximately 50% of adult patients with urticaria pigmentosa. There is flushing, syncope, and hypotension. Bone is the most common organ involved after the skin. Bone pain is a presenting symptom. Patients have diffuse or focal bony lesions that may be seen radiographically. Gastrointestinal tract involvement presents with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. Infiltration of the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes causes hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Mast cell leukemia occurs in fewer than 2% of patients. It is the most aggressive form of mastocytosis. There is malignant transformation in 7% of patients with juvenile-onset systemic disease and in approximately 30% of patients with adult-onset systemic disease.

DIAGNOSIS. The diagnosis is made by bone marrow histologic examination with immunohistochemical studies. Mast cell immunophenotyping, cytogenetic/molecular studies, and serum tryptase levels assist in confirming the diagnosis.

Mastocytosis should be suspected in patients with recurrent anaphylaxis who present with syncopal or nearsyncopal episodes without associated hives or angioedema.

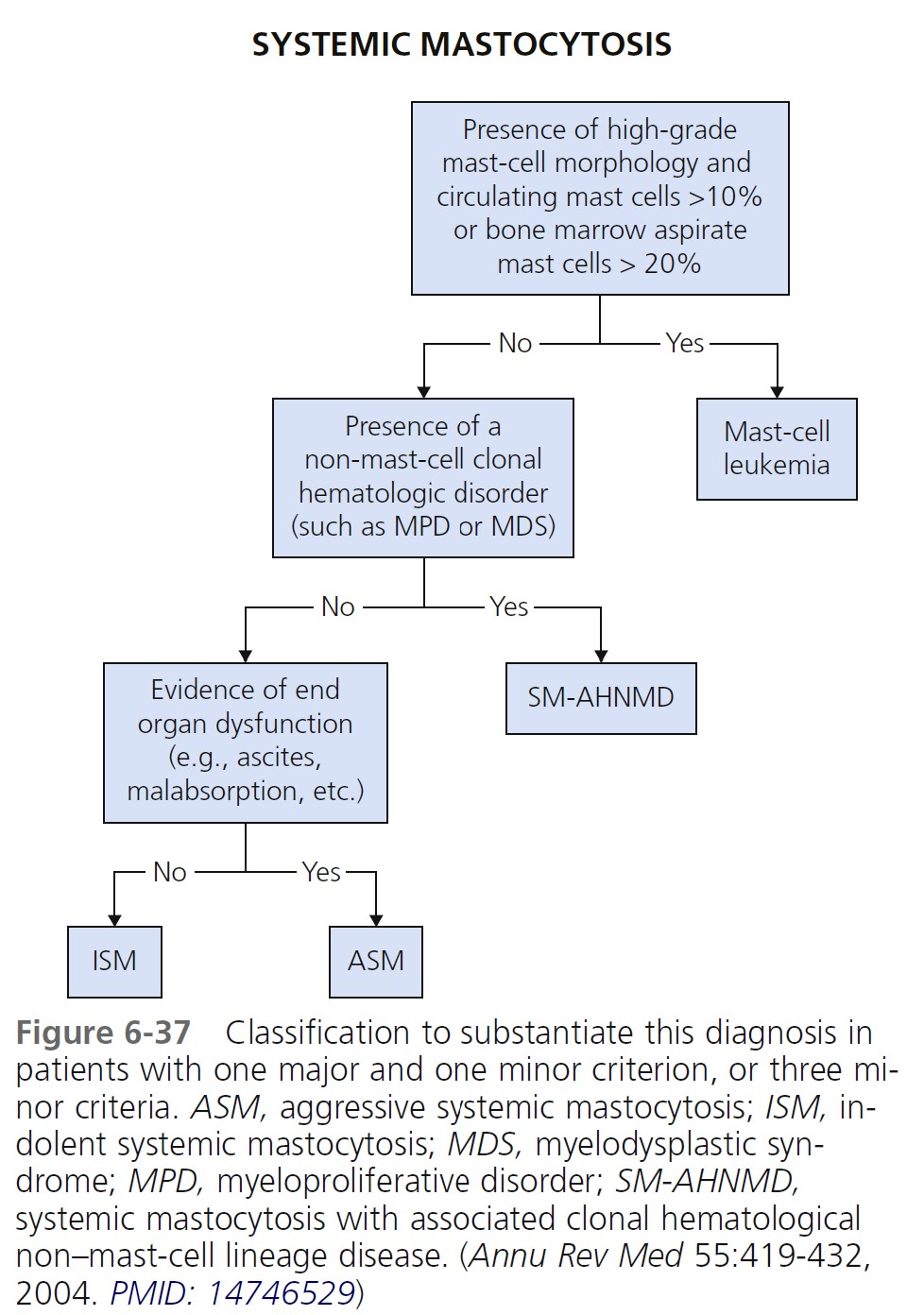

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR SYSTEMIC MASTOCYTOSIS. The diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis (SM) is made when at least one major and one minor criterion or at least three minor criteria are fulfilled ( Box 6-14 ). An algorithm for classification of systemic mastocytosis to substantiate this diagnosis in patients with one major and one minor criterion or three minor criteria is shown in Figure 6-37 . The cutaneous and systemic variants are listed in Table 6-6 .

DIAGNOSIS.